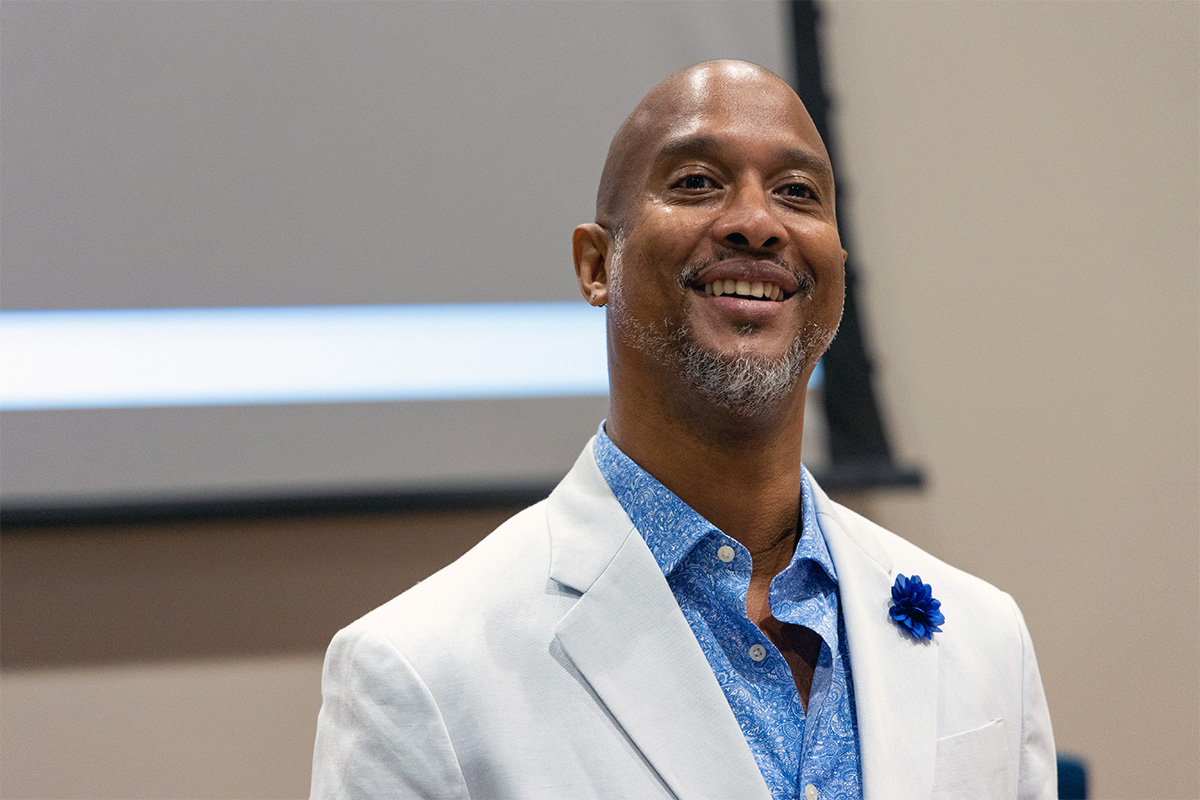

The search for new evidence to bring legal accountability for those involved in the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi during the Jim Crow era continues, filmmaker Keith Beauchamp says. He and other advocates for the prosecution of Carolyn Bryant Donham for her role in the Black boy’s death are frustrated that a Leflore County grand jury again declined to indict her, even after Beauchamp and Till family members found her unserved 1955 arrest warrant in June 2022 in the courthouse there.

But Beauchamp, the family and their supporters are still hopeful. Beauchamp, who is on the advisory board of the Mississippi Free Press, believes a large-budget film he co-produced and co-wrote will create the necessary buzz to generate more evidence.

“Till” comes out in theaters worldwide in October 2022 just weeks after the Mississippi grand jury again rejected efforts to finally prosecute the wife of one of Emmett Till’s murderers. It focuses heavily on Mamie Till Mobley’s activism to bring her son’s killers to justice. Beauchamp, who is from Louisiana, worked directly with her on the case before her 2003 death.

“The whole purpose of producing a Till movie is—of course—to bring awareness to the greatness of mother Mobley and her courageous decisions to make sure that justice prevails not only in a son’s case, but justice prevails for anyone who’s been failed by white supremacy,” Beauchamp told the Mississippi Free Press this week.

“The most important thing about producing a Till movie like this is to hope that it will shake the trees so that a justice-seeking atmosphere could be formed that will allow people to feel comfortable coming forward with new evidence on the case.”

‘Set In Front of A Jury’

Two white supremacists later admitting lynched Emmett Till on Aug. 28, 1955, after Carolyn Bryant, a white woman and the wife of murderer Roy Bryant, accused the boy of flirting with her. Till’s mother later held an open-casket funeral ceremony for her son in Chicago to show the world his unrecognizable face. After an all-white jury found the men who lynched him (including Roy Bryant) not guilty, the two men confessed to the crime to Look magazine, which paid $4,000 for the interview. Roy Bryant and accomplice J.W. Milam died without seeing justice for their crimes.

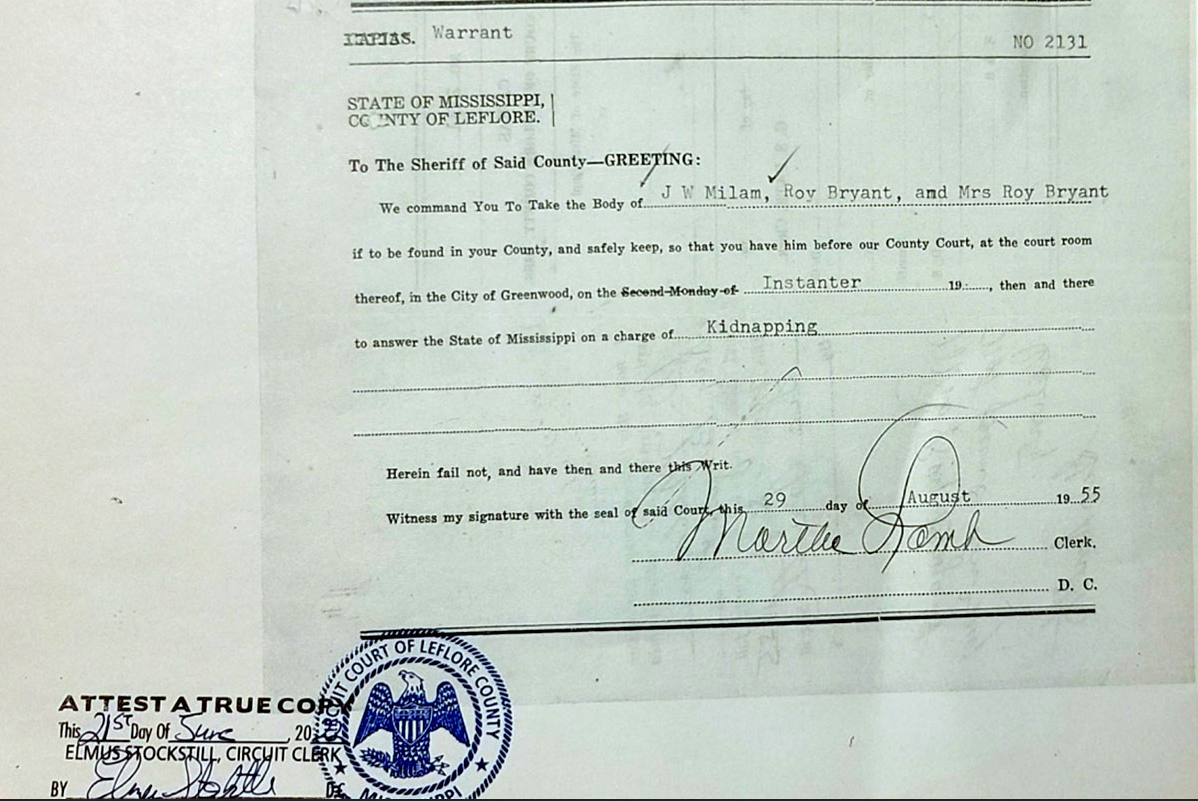

While searching the basement of the Leflore County Courthouse, in June 2022, family members with the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation, in collaboration with Beauchamp, discovered the 1955 warrant for Carolyn Bryant’s arrest over her alleged involvement with Till’s kidnapping. A Leflore County grand jury, however, declined to indict the 88-year-old, whose name is now Carolyn Bryant Donham, last month.

“(Donham) should be brought to the court of law and set in front of a jury to answer to what transpired in 1955,” Beauchamp said this week.

The Mississippi Free Press reached out by email and phone call to the office of the Leflore County District Attorney W. DeWayne Richardson, who is Black, for comments on Aug. 30, 2022. He did return calls as of press time.

‘Feeling of Deja Vu’

Keith Beauchamp released a documentary in 2005 on Till’s lynching called “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till.” In 2006, the FBI published a 291-page document of redacted findings in the case, but in 2007, a Leflore County grand jury declined to issue an indictment in the case.

In Baton Rouge, La., just days before the group found the arrest warrant in the Mississippi Delta, Beauchamp and two former FBI agents talked about the frustrations and difficulties over the decades in prosecuting the case. It was especially hard for the federal government due to legal strictures about crimes they can and cannot legally prosecute, they explained.

Former FBI agent Cynthia Deitle, who led the bureau’s Cold Case Initiative from 2008 to 2011 as chief of the civil rights unit, explained that three federal statutes could allow the FBI to prosecute cold cases. “One was kidnapping across state lines, one was murder on federal land, and one was use of an explosive device,” Deitle explained at Southern University. But Till’s murder met none of those three criteria.

That makes the need for a local prosecution of Bryant imperative, to Beauchamp’s thinking. He said the latest grand-jury decision to pass on the wife’s prosecution gave him the feeling of déjà vu.

“Although I respect the grand-jury decision, that does not mean that I necessarily have to agree with it, and I don’t agree with it,” Beauchamp said. “Am I surprised or shocked that that decision was actually made? No, I am not shocked in any way. Disappointed? Yes, but not so much shock—because it is something that I expected, being that I was part of the original investigation before, and we had the same result in 2007 when it went to a grand jury.”

“So it’s just more of frustration that I feel because of the fact that it seems to be the same system that befell Emmett Till in 1955 and allowed his murderers to go free—it is the same type of atmosphere and system that we’re dealing with,” Beauchamp added.

“And so one would hope that I would be able to say that things have changed in Mississippi, in particular, the Delta, but I can’t say that to be true because I firmly believe that same system that protected Till’s murderers in 1955 has allowed Carolyn Bryant Donham to evade justice for so long.”

Donham lives in seclusion outside Mississippi and does not do media interviews.

Protest At Mississippi Capitol

Columbus, Miss., resident Kamal Karriem drove 170 miles to Jackson, Miss., on Aug. 27, 2022, to participate in a protest calling for Emmett Till justice alongside other Black activists at the Mississippi Capitol to mark 67 years since Till’s death. Karriem is a member of the Mississippi Black Liberation Movement, an organization based out of Coldwater, Miss. He is also one of the two plaintiffs in a case decided in the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Aug 24, 2022, upholding laws that lead to the disenfranchisement of disproportionately more Black than white residents of the state.

In a phone interview on Sept. 7, 2022, Karriem said the U.S. Congress needs to wade into Emmett Till’s case after the August grand-jury decision. His group and others had sent a petition letter delivered to District Attorney Richardson, which Karriem said several people signed, asking for the convening of the grand jury after the 1955 warrant surfaced, as many Black Mississippians wanted to happen.

“The only thing that we can do now is ask Congress to press the DOJ to reopen the case,” Karriem said. “That’s the only avenue that we have—asking Congress to get the Department of Justice to reopen this case.”

Then-President George W. Bush signed the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act in 2008. The late John Lewis, D-Ga., introduced the bill. It asked the DOJ to investigate and prosecute “violations of criminal, civil rights statutes that occurred not later than December 31, 1969, and resulted in a death.”

In March 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law, which Rep. Bobby L. Rush, D-Ill., introduced. It imposed a jail time of 30 years for perpetrators of any hate crime “that results in death or serious bodily injury or that includes kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill.”

In Baton Rouge in June, the former FBI officers emphasized that the agency did not really investigate the murder of Till after it happened. And there was one option they could have used, former Agent Deitle said.

“The one statute that we could have used was a conspiracy statute that was passed in 1948 under federal law. It was a federal conspiracy statute (against) two or more people conspiring to violate someone’s civil rights,” Deitle said at Southern University.

“We tried that in the ‘Mississippi Burning’ case: the murders of (Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman). We used that statute amongst others to prosecute those perpetrators, and the Supreme Court upheld it.”

In the Philadelphia, Miss., case several Ku Klux Klan conspirators went to federal prison for several years for civil-rights conspiracy for kidnapping and killing civil-rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. The only one who ever served time in state prison was lynch-mob organizer Edgar Ray Killen, whom then-Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood finally successfully prosecuted for manslaughter in 2005 in front of a Neshoba County jury.

But the feds declined to use the conspiracy strategy against Till kidnappers and murderers. And no local grand jury has moved a case forward since the original trial with all-white jurors in September 1955.

Beauchamp still has hope for Leflore County—which is now majority-Black—but said it would be six months before the complete picture of what transpired with the Leflore County grand jury could come to light. The Mississippi statute says that a juror “shall not disclose any proceeding or action had by the grand jury in relation to offenses brought before it, within six (6) months after final adjournment of the grand jury upon which he served.”

“So a lot of us are sitting by, idling by waiting to hear if there’s anything that’s going to come out after the six-month grace period, in terms of being able to dig deep and see if there’s any more information you could find out about the grand jury and how the case was presented,” he said.

‘Grand Ole System’ of White Supremacy

Kamal Karriem told the Mississippi Free Press that the information he obtained indicated that the grand jury that declined to indict Donham was composed of 80% Black jurors and 20% white jurors. Beauchamp said the jurors’ demography does not preclude the influence of what he regarded as white supremacy in the case.

More than 75% of Leflore County’s population is Black.

“Regardless of who is serving their duty, you are still faced with, I feel, the same judicial system that failed us in 1955,” he said. “So whether it’s a mixture of Black or white, majority Black, none of that matters when you talk about the Delta of Mississippi, because the powers that be that held or allowed these people to go free before, these people are still prevalent; they are still a part of that grand old system.”

“So until those folks seem to die away, until those folks who influence people in the Delta are gone, I don’t see any change, not only in the Delta, in Mississippi, but even around the country, because the Delta is only a microcosm of what we see throughout the South,” Karriem added.

“But the Delta is a very interesting and particularly rare place as well, because this is where that Dixiecrat hatred comes from, and so there’s a lot of history that tells us, even present day, what we are dealing with when we talk about the judicial or criminal-justice system throughout the Delta of Mississippi itself.”

“Dixiecrat” is the nickname, first, of the States’ Rights Democratic Party, which was formed after members of the Democratic Party in the southern part of the United States split from the party in 1948 in opposition to desegregation moves. The racist southern Democratic Party continued to be referred to as Dixiecrats until the party split with a revamped Republican Party welcoming former Dixiecrats into its soon overwhelmingly white party.

Karriem said he believes that the outcome would have been different if Donham had been Black. “It is a white privilege that takes place and supersedes equity and justice,” the Columbus resident said. “Because if Carolyn Bryant Donham was my 86-year-old Black mother, that warrant would’ve been served; she would not have been able to be above the law just simply because it would not have been told to people that justice should have a shelf life with age.”

Karriem credited the story of civil rights leader Medger Evers as a factor for his activism in this cause. On June 12, 1963, Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the Ku Klux Klan and the Citizens Council, shot and killed Evers outside his Jackson home in front of his children.

After two unsuccessful trials, a jury convicted Beckwith in 1994. He died in the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson after being transferred there from prison.

“You know, we are not being racially prejudicial towards Carolyn Bryant Donham,” Karriem said. “We just want justice. It would be the same as if it was a Black person, but we don’t want white privilege to supersede justice as it does in Mississippi—it always has.”

Beauchamp pointed out that the Leflore County sheriff is white despite the white population being so low there. Fredrick “Ricky” Banks is in his seventh term in office since his first election in 1979.

“So how do a majority-Black county and city (county seat Greenwood) allow someone to sit in that position from the ’70s?” the filmmaker pondered.

“What I’m saying is despite the demographics of those who may have served on the grand jury, whether they’re white, Black men, women, that doesn’t matter,” he said. “When you look at the system of white supremacy, people are still in control of being controlled in some ways, people are still being influenced in some ways.”

‘She Has Two Small Children’

At the Aug. 27, 2022, rally in Jackson, Local Organization Committee of Greenville Co-chair Kareem Muhammad said Carolyn Bryant Donham needed to be “brought to court.”

“We are standing here on behalf of that warrant and saying that the Mississippians here are outraged—the Black community—we’re outraged for the lack of efforts that have been made by the criminal-(justice) system here in Mississippi in executing that warrant,” Muhammad said.

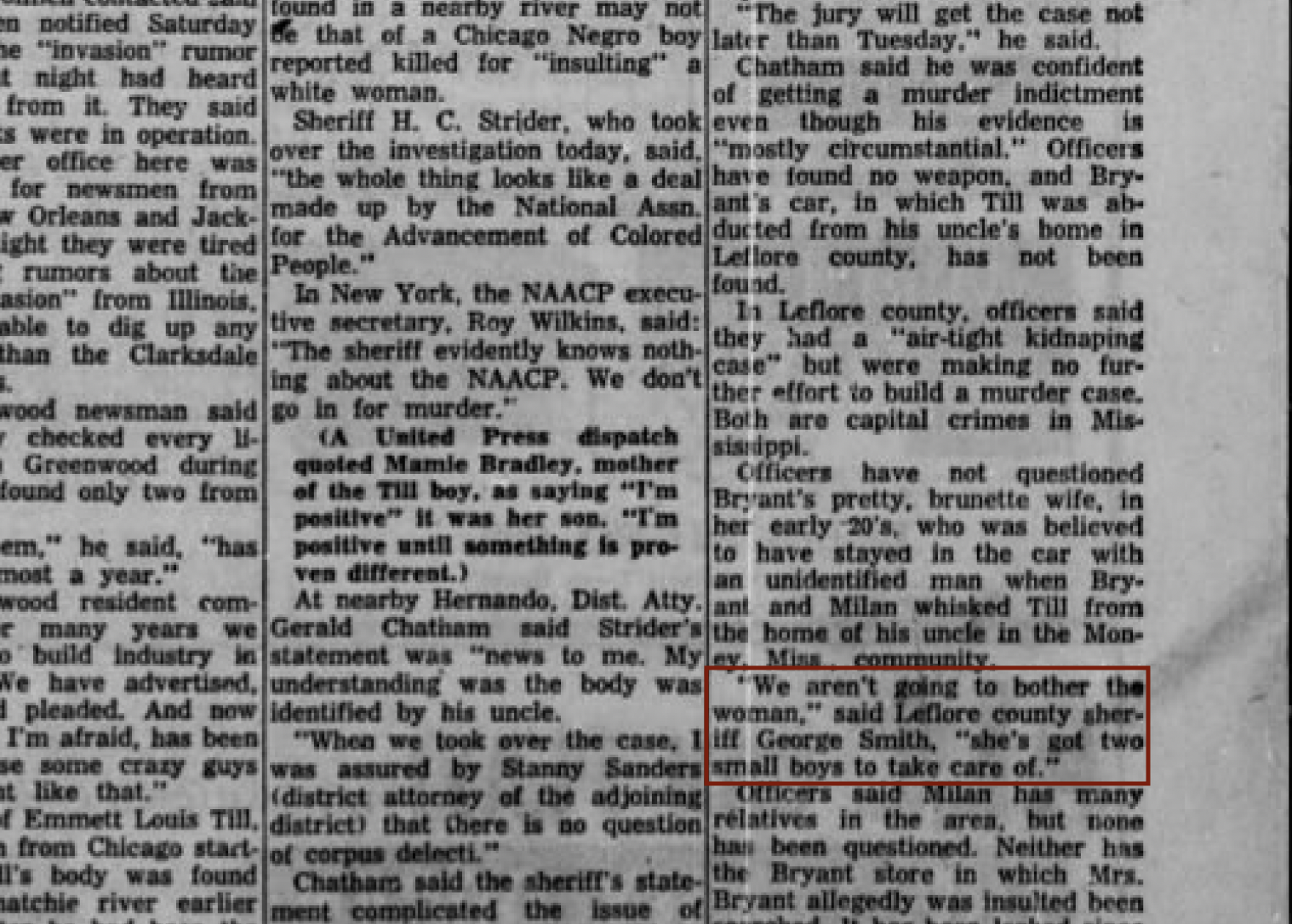

Karriem pointed out certain parts of Till’s case that were concerning to him, including the reason that Leflore County Sheriff George Smith gave in 1955 for not serving the warrant on Donham. “He felt that because she had two small children that she didn’t need to be bothered with the matter, but there were witnesses that said that she was actually in the truck that pointed out Emmett Till, who was a 14-year-old child at the time of his murder,” he said.

The then-virulently racist Clarion-Ledger reported on Sept. 4, 1955, that the sheriff gave a reason why he did not question Donham. “Officers have not questioned Bryant’s pretty, brunette wife, in her early 20’s, who was believed to have stayed in the car with an unidentified man when Bryant and Mila[m] whisked Till from the home of his uncle in the Money, Miss., community,” the paper reported.

“We aren’t going to bother the woman,” the story reported the sheriff saying. “She’s got two small boys to take care of.”