COLLINS, Miss.—Honestly Beef co-owner Jaclyn Lee Rogers coasted the golf cart to a stop at a pasture containing cows of brown, white, black and a reddish-orange hue. Red tags adorned their ears, and brands appeared near their hind legs to differentiate which cattle belong to whom. Caroline, Rogers’ 7-year-old daughter, unlocked the gate where more than 20 cows were getting their daily feeding from recycled tires.

“So we take tires and turn them inside out. They flip them, and they hold feed,” Rogers said. “A tire will never rot. We’ll have the things that hold the feed right here, and we’ll move them over to let the land heal. These are newer cows.”

The cows were no more than a few feet away, some venturing closer, curious yet cautious. Rogers’ daughter stepped off the cart to get closer and touch one, but the cows immediately fled in a herd, kicking up dust amid a backdrop of clear, blue skies and green trees. It was an amazing sight despite the potent smell of manure and the incessant buzzing of flies.

“You ain’t got your magic touch today, sister,” Rogers joked to her daughter.

The grass-fed cows had transitioned to eating feed because the hotter weather dries the grass out, which isn’t healthy for the cows to consume, she said. They mix their own feed because they have so many cattle, buying products that are on the brink of going bad, like orange peels and peanut skins from an M&M factory.

In a year, these same cows will reach 1,100 to 1,300 pounds and will be ready for processing at a kosher plant and sold under Honestly Beef, a community-supported agriculture business, or CSA, based in Collins, Miss. Spruce Eats defines a CSA as “a food production and distribution system that directly connects farmers and consumers.” Consumers place an order for beef on Honestly Beef’s website and have it delivered to their doorstep.

“I wanted to be able to sell to somebody like me when I was younger. I live in the middle of a 1,000 acres of cattle, and I was having to go to Walmart myself and buy the crappy meat,” Rogers said in a phone interview in late May. “I wanted to be able to sell to the local people, not just the restaurants or the people who had the money to buy a whole cow.”

‘Blew Up Like Crazy’

Next to the computer inside the Honestly Beef office where Rogers packs all the orders was a stack of orders from Friday to be completed, and on her computer were Monday’s orders. Freezers containing various meats from the farm’s website lined the walls. Sirloin steak, New York strip and rib-eye were in one freezer, while short ribs, brisket and petite medallion occupy another. Boxes of beef jerky in various flavors lined the back wall of the office. One side of a freezer that holds ground beef was empty due to high demand in the wake of COVID-19.

The Centers for Disease Control reports outbreaks of the virus in at least 115 meat- and poultry-processing plants in 19 U.S. states. That includes close to 5,000 cases and at least 20 deaths among plant workers.

“This is usually my two-pound packs of ground beef. They’re already gone. I had too many briskets, so they overflowed into this,” Rogers pointed out.

Behind the office is the trailer she uses for farmers markets, which houses another collection of freezers that can hold up to 900 pounds of ground beef and one that can hold a whole cow. The trailer’s skin shows a field of cows and facing away from the camera, with their backs turned, are her two daughters, Caroline and Madlyn, dressed as farmers.

“When I go to a farmers market in this, it stands out from other farmers because typically it’s just in the back of a dirty farm truck. I wanted actual pictures of our stuff,” she said.

Honestly Beef started in 2013 after Jaclyn convinced her husband, Bernie, who had raised cattle all his life, to sell the meat. The cattle farm in total is 12,000 acres that stretches across Pearl River, Simpson, Covington and Jefferson Davis counties, housing 61,000 cows. They employ 20 workers on the farm, but Rogers mostly handles paperwork and the packing and shipping of the product by herself, she said.

Their meat is U.S. Department of Agriculture-inspected, growth- free and hormone-free, and it is processed through a kosher plant in Summit, Miss., meaning the farm adds nothing to the meat at the time of processing. Rogers mostly frequented farmers markets to sell her product, going three times a week on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. However, things changed once everything shut down due to the pandemic, she said.

“When all this shutdown happened, I kicked up my shipping. I ran a radio ad on the Coast, and that blew up. I told them to use the code radio at the check out, and they would get free shipping. And oh my goodness, that blew up like crazy,” she said.

She was shipping six to eight beef boxes, which hold about 25 pounds of meat, a week before the pandemic. Now, she’s been shipping 120 to 125 boxes a week. The boxes have insulated lining, which holds the meat for 72 hours. Outside Mississippi, she has done two-day shipping to states such as Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, the upper parts of Florida, Texas and Georgia, she said.

“There was one order, and it was a two-day ship, and it was in Virginia. I did like two in Virginia,” she said. “They had relatives who lived in Lucedale, Mississippi, and told them about me. They weren’t able to get meat up there (in Virginia), and so they emailed me and asked if I could ship to that zip code.”

What she enjoys most about the job is that she’s always busy, and it’s never ending, she said, and at any time, she can be called to do something.

“Somebody will say there is a cow out, and nobody else can go get it. Me, her (Caroline), and (Madlyn), you ought to see us try to catch them. (But) the Honestly Beef part I enjoy because I get to share the meat with people,” Rogers said.

‘A Lot More Doing Business’

Jaclyn Rogers’ method of selling her product online is what Elizabeth Canales, Mississippi State University assistant agriculture professor, would call an example of using ecommerce, short for electronic commerce. That means farmers can post the items or subscriptions they sell in an online shop.

“You see a lot of people using ecommerce, whether it’s a simple way for smaller producers or just actually using websites (and) e-commerce platforms,” Canales said. “You’ve seen people that did not use those platforms before because you don’t have access to those consumers directly as much anymore, assuming you just sell at farmers markets.”

Canales notes that the recent interest in CSAs is in part due to consumers wanting to support producers and also wanting to escape exposure to COVID-19 by avoiding the grocery store.

“I talked to a lady who has a CSA in Colorado, and what she was telling me was that some of the people that buy from her have immunocompromised issues,” she said. “They don’t want to go to the grocery store. If you’re buying from a producer, you know the producer touched those products, but it hasn’t been touched by a lot of people.”

The assistant professor could not give a quantifiable number of how many CSAs are in Mississippi. On sites like Local Harvest, for example, farmers create online profiles, but do not update their information, Canales said.

“It’s hard to know how many, and you have different levels. You have very informal CSAs and different versions of what a CSA could be. I would like to give you a number, but from what listings I’ve seen maybe 25 to 30,” she said.

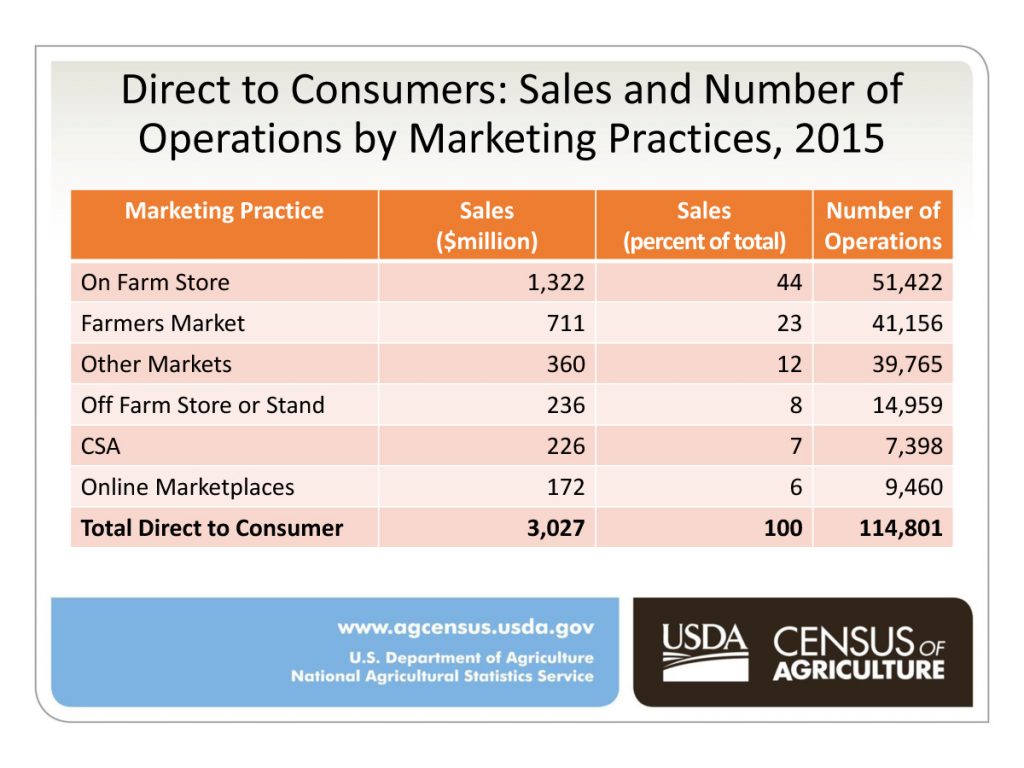

The 2015 USDA Agriculture Local Food Marketing Practices Survey reported 7,398 CSAs out of 114,801 operations that market directly to consumers. And CSAs make up 7% of food sales, which equates to $226 million.

“I’m sure there are a lot more doing business in different ways that it’s not that visible or that we can’t account for,” Canales said.

The inability to access those numbers is a problem that has a lot to do marketing. Whereas farmers are more concentrated on being in the fields and planting the crops, they suffer in the marketing department, she said.

“As a CSA you have to market your product, you have to do good marketing,” Canales said. “Otherwise people won’t know about your service. People that have good marketing are using social media and online platforms, ecommerce, (and) a lot of them are sold out. They have reached their sales that they would have for the year in some cases.”

Both social media and her radio ad have been powerful tools for Jaclyn Rogers, as her sold-out products show. Even food she gives away for free creates a big demand. Rogers said, at one point, she had so much liver left over from her cows that she put an ad on Facebook to give it away. The post garnered 31,589 views, and she eventually deleted it.

“Can you believe the phone calls and the messages? I could not do anything that day. I’ve never had that much response on a Facebook post. I got rid of all the liver. Man, they were lined up out here. I had people driving over an hour away,” Rogers said.

Dr. Canales is curious as to whether this big demand with CSAs will retain itself after the pandemic ends, but she certainly hopes so.

“I think the pandemic has exposed issues in the food-supply chain where people were used to going to the supermarket and having everything available,” the professor said. “Because of the pandemic they’ve realized that someone is actually transporting this product. People have been forced to think about food more and who is producing the food.”

Good Food, Bridging Divides

Farming is in Rickey Cole’s blood. His father and grandfather were in the produce business, selling produce wholesale, he said. Cole now owns 160 acres of family-owned land in Jones County, where he grows the fruits and vegetables for his new produce service, Cole Farms.

“I come from a long line of farmers, and farming has been my occupation all my life. Farming has been my livelihood,” Cole said in a phone interview in early June.

Before the pandemic, Cole’s produce had been selling out at farmers markets. After customers and friends approached him about growing vegetables and fruits for them, he transitioned to planting crops and taking memberships for home-delivery service, he said. He mainly serves the Gulf Coast, the Pine Belt and metro Jackson.

“It’s a small project. We only have about 200 customers. We’re delivering once a week. The summer project is 20 weeks,” he said. “We’ll deliver to our customers for 20 weeks solid all the way through September. Then we’ll have a fall and winter program that will probably be once or twice a month in deliverance.”

Cole said the increased interest in CSAs shows that people want to know where their food comes from, especially since the pandemic has multiplied consumer fear.

“I think it’s a natural outgrowth from a lot of the relationships that have been developed at farmers markets. A lot more people this year than in recent years have started their own home gardens as well,” he said.

Cole Farms is a more traditional CSA that deviates from the ecommerce route and relies more on word-of-mouth and a familiar, supportive consumer base. But this method hasn’t slowed business down for him in the least bit. Since the pandemic, Cole has reached capacity on how many customers he can serve and cannot take anymore memberships, he said.

“I just haven’t been able to meet the demand. My operation is small, and I don’t intend for it to get too big. I want to be able to manage the quality and not quantity,” Cole said.

The farm grows a variety of fruits and vegetables such as garlic, squash, onions, okra, greens, sweet potatoes, watermelon, cantaloupes and more. Cole said he’s also surveying customers on what crops they want, planting 40 different varieties of seeds that amount to about 25 to 30 crops.

We try to produce it with traditional old-school methods. Many of the seed varieties and agricultural practices that I use are ones my parents and grandparents used,” he said.

He uses a minimum amount of chemicals and prides himself on his hands-on approach to planting, tending and harvesting.

“For a crop like watermelons, by the time that watermelon gets to you, my hands would have touched that probably 10 times from the time I plant the seeds, to the time I set it out, to the time I work around it, tend it and pick the watermelon,” Cole said. “So when I say hands-on, that’s literally what I mean.”

Cole plants everything in season and doesn’t pick his fruits and vegetables for delivery until they’re ripe and ready, a method that differentiates him from commercially grown food, he said.

“I remind my customers that I’m not going to produce something when it’s not in season. I’m not gone try to bring you tomatoes for Christmas. I’m not going to try to bring you cabbage for the Fourth of July,” he said.

Cole said he loves to feed people and sees food as having the power to bring people together. It’s what’s keeping him going, he said.

“I think a lot of our division and mistrust and hatred in Mississippi could melt away if we would find ways to break bread together and have strong relationships surrounding the food that we eat,” he said.

Dissolving Food Deserts?

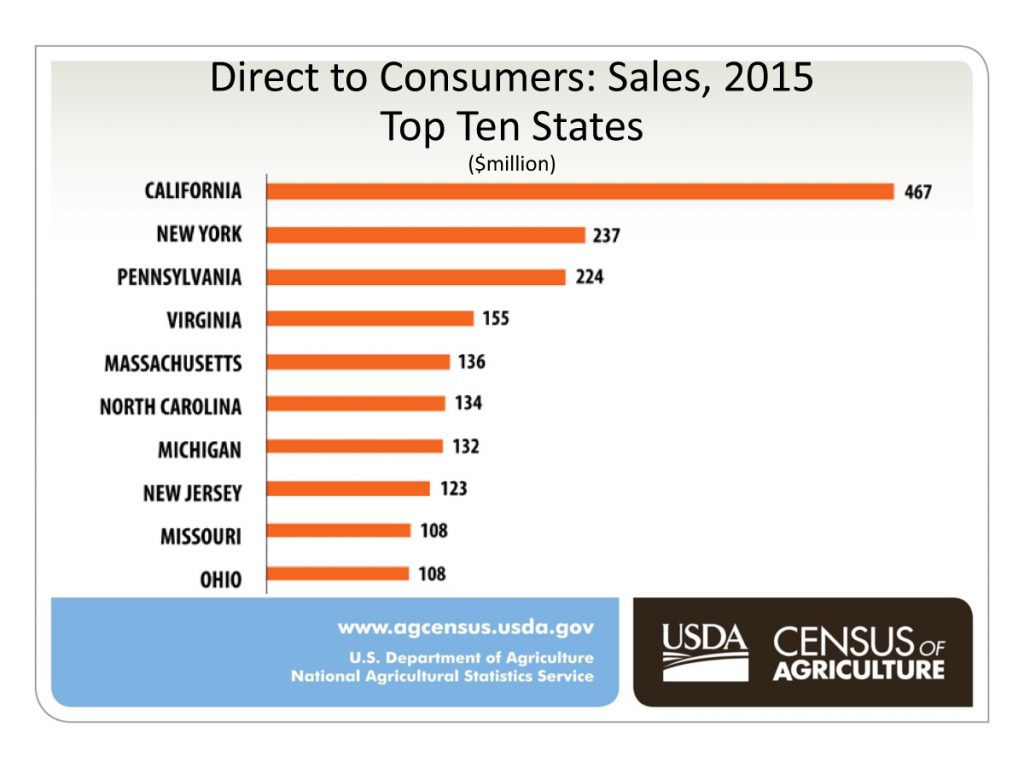

The 2015 USDA Agriculture Local Food Marketing Practices Survey reported that the top 10 states with the most in direct-to-consumer food sales were mostly states on the East and West Coasts. North Carolina was the only southern state on the list, coming in at No. 6 with $134 million in sales.

Rickey Cole said Mississippi has some of the richest land in the western hemisphere, but we aren’t using it to produce food for the people who live here. He ran for commissioner of agriculture last year for that very reason, but he did not win.

“We do not make best use of our land or of our people. There are a lot of people who can and should be making a good living producing food for their neighbors. The state of Mississippi does little to nothing to encourage that,” he said.

Cole believes CSAs could be a solution to dissolving food deserts.

“We need to make some cultural changes to make it a matter of course for people of all economic levels to be able to produce, buy and sell locally produced food in season,” he said.

Canales said she has spoken to colleagues who work in ecommerce, and one colleague in Alabama is working with CSAs to combat food deserts.

“I’m going to speak with him more about it, (but) there are different strategies you can use. I definitely think a CSA type of program can be very useful in tackling those issues of food access,” she said.

The caveat is that local food can sometimes be more expensive than commercially produced food, she said. Efficient farms are more mechanized and of larger scale, producing at a smaller cost in comparison to smaller-scale farms, Canales said.

“We can use the tools and technologies that’s available to tackle those issues,” she said. “If a farmer just grows one crop or a couple of crops, I think there’s an opportunity for them to partner with other growers and create variety farms. I would like to see more of that. I know it’s more difficult to coordinate, but it’s definitely an option.”

Cole said Mississippi is spending billions of dollars outside the state to buy food that people can produce locally. Thus, CSAs could have an impact on Mississippi’s economy if people would consider them, he said.

Dr. Canales couldn’t give a definitive number on the sales that people in Mississippi could accumulate, but researchers are studying the economic impacts of CSAs.

“The neat thing is there’s a lot of imported products coming from other states, but small- and medium-scale producers cannot sell to Walmart or Kroger,” she said. “You are able to support those farmers, and (they) are viable because they have a market outlet in direct-to-consumer marketing. That’s why they can stay in business and hire people.”