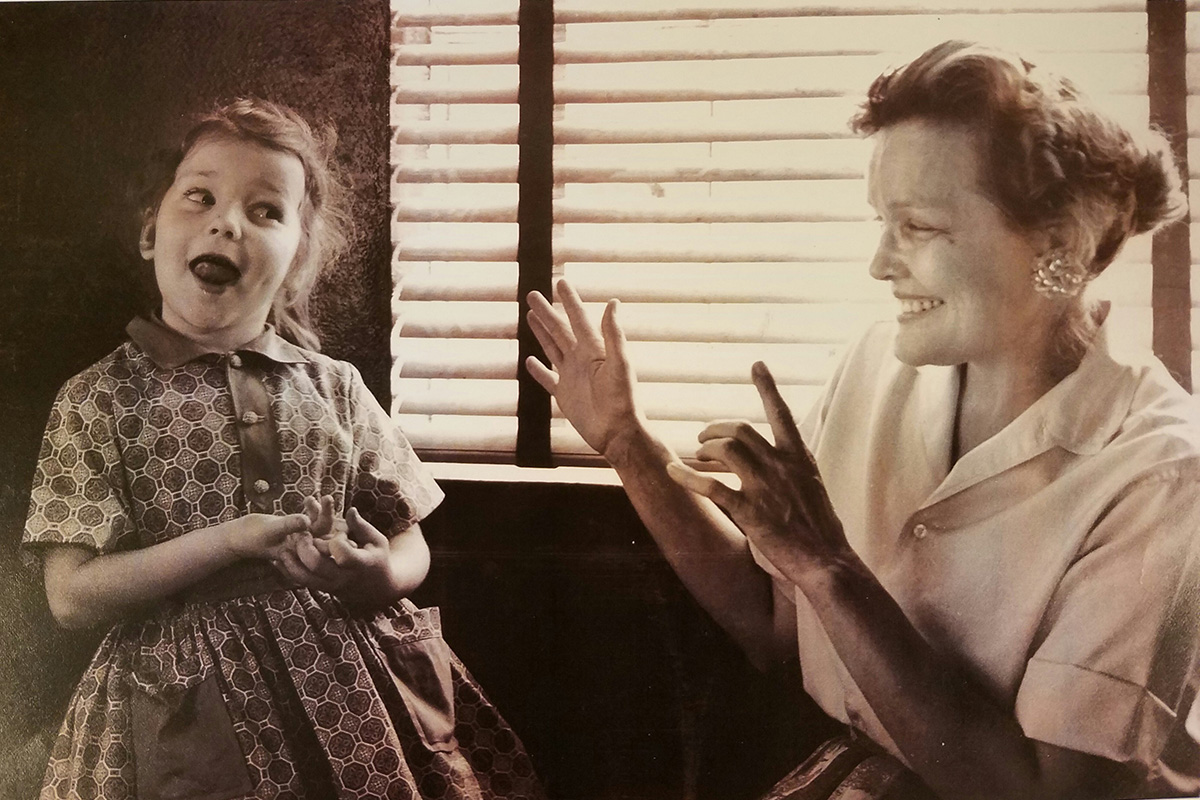

JACKSON, Miss.—After Elizabeth “Libba” Matthews birthed her son, Keith, she quickly recognized that he was deaf. She took him to a doctor in Jackson, with questions lingering in her mind as to how her son was going to learn and where he would attend school. The doctor suggested she enroll Keith in the state school for deaf children, but Matthews didn’t want her son to sign, Magnolia Speech School Executive Director Valerie Linn recounted.

“She wanted him to be listening and speaking because that is the world that we live in. She was a determined mother,” Linn told the Mississippi Free Press.

The doctor gave Matthews some information on the Central Institute for the Deaf, or CID, in St. Louis, Mo. The family moved there, and she got an assistant position at the institute. The staff noticed Keith’s progress and how involved his mother was in his growth and subsequently offered her a work study, allowing Matthews to begin working in the classroom and learning the methods the school used to teach deaf children.

Matthews later moved back to Jackson and founded the Magnolia Speech School in 1956 in the living room of her own home. “Keith stayed at CID and was a residential student there for years before he came home. It’s kind of a model for what Magnolia had through the years,” Linn said.

Speech-language deficits are the most common childhood disability, affecting around one in 12 children. Without treatment, speech-language problems can lead to behavioral challenges, mental-health problems, difficulty reading and academic failure.

The Magnolia Speech School is a nonprofit school established with a mission to help children with communication disorders develop their potential through spoken language and literacy. The program takes kids as young as 1 year old up to age 13.

“Our goal is to close the gap that’s caused by their language challenges and get them into a more traditional school setting or the school of their parents’ choice,” Linn said.

The school has a racial demographic of 61% white, 28% black, 8% Asian and 3% Hispanic students. Twenty-three percent of students attending Magnolia are hearing impaired, and 76% of students have a language or speech impairment. Male students make up a majority of those enrolled with 58% while female students are 42%.

Unlike a traditional school setting, the classrooms are smaller with five to eight children per class with a certified teacher and assistant assigned to each class.

“Our teachers are very experienced and educated in their particular areas. Our teachers are teachers of the deaf, or they might be special-education teachers with emphasis on speech and hearing. We (also) have undergraduate teachers with a bachelor’s in communication disorders,” Linn said.

The facility plans to move from its secluded spot on Flag Chapel Road in Jackson to a site off Bozeman Road in Madison.

‘Building Hope’

The cost of tuition for Magnolia equates to more than $29,000 per child, but no family pays even half the costs, largely because the nonprofit school looks at the work they are doing as a service to the community, the executive director explained.

“The tuition is based on a sliding-fee scale, so the lowest anyone pays is $550 and the highest anyone pays is $980 a month,” Linn said.

Sliding-scale fees are based on tax returns, so parents who earn the least, pay the least, and those who earn more, pay more. Many of the school’s students also receive funding from Education Scholarship Accounts, vouchers that allow parents of children with special needs to withdraw them from public schools and enroll them at private schools that offer those services.

With ESA, a child can receive up to $6,500 a year to cover tuition at a special-purpose school, if they have an eligibility ruling and IEP, an individualized education plan. But there’s still tuition and operational costs to cover, which the school makes up in fundraising and support from the community.

“We have to raise about $800,000 every year,” she said. “We have a lot of great foundations that support the school, foundations that have to do with children’s education, hearing loss, special education. We write a lot of grants, and we have a lot of support from the community, and that’s why Magnolia has survived all this time.”

Fundraising has also helped with their “Building Hope” campaign, which started in 2018 after the school’s board of directors approved the purchase of 6.5 acres of land in Madison County for a new structure. After two years, the school managed to raise 80% of the funds needed and on Oct. 22, 2021, they announced the groundbreaking of the new facility for the Magnolia Speech School.

The institution’s building has been situated off Flag Chapel Road in Jackson since 1974. A supporter of the school donated the land on which the school resides, and the structure was built with help from the surrounding community. However, the 47-year-old building has undergone some changes over the years.

“We’ve got tiles popping up in places on the floor. We’ve got a big crack on the west side of the building,” Linn described. “We have loved this spot, but the maintenance of the building just became a bit harder and harder each year to keep the building cool in the summer and warm in the winter. We had to replace the HVAC system.”

The new 30,000-square-foot facility will include construction materials as well as educational and therapeutic technology tailored to accommodate the needs of kids with hearing loss and communication disorders. The new school will also include an expanded clinic for outpatient services, two new playgrounds, a library built into the end of the property and surrounding landscape, new AAV auditory visual components and a new soundproof booth for their audiologist.

Although the nonprofit has 80% of the funds covered for the building, they are looking to receive the remaining 20% from individual donors.

“We’re coming to the public and saying, ‘What’s your best gift?’” Linn said. “It might be $100, (but we appreciate) anything like that to help us close off the costs and close up the campaign so that we can just continue to do what we do best.”

‘Visibility’ on a Busier Madison Thoroughfare

The new location offers the school more visibility as it not only sits close to the interstate, but it will also sit on a busier thoroughfare opposed to the more secluded spot they occupy in Jackson.

“Bozeman Road is so traveled right now and, honestly, I’m a little bit anxious about that because we gotta think through what traffic is going to look like,” Linn said. “It’s gonna be a real blessing and a little bit of a challenge when we first get out there.”

The executive director said the school board conducted a survey of where the children that attend Magnolia live, as well as the school’s staff. Although the largest portion of Magnolia’s enrollment comes from the metro Jackson area, the institution also found that families moving to the area to enroll their children typically settle in the Madison or Ridgeland area.

A majority of the staff lives in Brandon, and one assistant teacher, whose daughter attended the school, even commutes from Simpson County every day. For the current enrollment year, the school has three students attending that moved from out of the state. The school doesn’t have buses, so the new location may mean a longer commute for some.

“We have a family who drives from Coffeeville, Miss., two hours away, for their child to go to school here. Unfortunately, that’s just kind of the nature of our school,” she said. “That’s really kind of the parents’ choice, but honestly they always think, ‘This is where it’s better for my child right now. We’ll make the sacrifice right now.’”

Buses used to be offered when the school district was helping to cover the costs for children to attend Magnolia. So what changed?

“Well, it’s up to the school district. We know and probably the school districts know that a child here getting services all day long is really the best thing for them,” the director said. “(But) when you’re in a public school, it has to be free and appropriate. So, they say, if we’re offering a speech pathologist or a dyslexia therapist, then we’re doing our part.”

Linn said unless a parent really pushes for their child to attend Magnolia, it is very difficult to get the school district to collaborate with them.

“We do have one school district, and they’re sending a child who is hearing impaired because they recognize if this child can get as much as she needs before she’s in the first or second grade, then that’s the best thing for her,” she explained.

In this case, the school district will pay Magnolia so that the child gets all the services they need. And when students are transitioning from Magnolia to a public school, the school will go with parents to assess the classroom and work with administrators on the child’s needs for their new setting, Linn said.

“Does the teacher have a sound-build system or other auditory system that allows the child to hear her voice? There’s these things called a Roger pen. If the teacher wears a little mic around her neck and the child wears a receiver to help them hear her voice better, then they get a more pure speech sound and they can hear better. … It’s the school district’s responsibility to purchase that,” she said.

ESA Vouchers vs. Public Schools

ESA vouchers give parents the ability to use state funds to pay private-school tuition for children with special needs, essentially moving public funds to private schools. While the ESA vouchers help schools like Magnolia, they also deal a blow to public-schools funding and the work they could be doing for special-needs students, public-school advocates say.

Parents’ Campaign Executive Director Nancy Loome calls ESA vouchers unconstitutional as the Mississippi Constitution states that public funds should only be used for free schools that do not charge tuition.

“We have all kinds of ways of holding public schools accountable, but the private schools that receive these voucher funds have no accountability to the public at all,” Loome told the Mississippi Free Press. “They are able to keep secret how they spend the funds. There are no set standards that they have to abide by in order to receive the funds.”

Loome said that every year more than half of the vouchers parents apply for go unused due to three reasons. A legislative peer committee found that one reason was due to private schools denying the child entry, the second was due to parents having difficulty finding a school that suited their child’s needs, and the third was due to parents not being able to afford the leftover tuition balance even with a voucher.

“As of last December, of all the children that had been given vouchers, 39% of them had used them. Sixty-one percent of the students who were given vouchers did not use it,” she said.

Special education, meanwhile, receives less funding from the Mississippi Legislature, which routinely underfunds the Mississippi Adequate Education Program requirements, she explained, adding that part of the missing public funds could go toward paying for special-education teachers.

“At the beginning of the year, (the district) does what they call child find, and they go out and identify every student in the district who has a special need and what that need is,” Loome said.

“Based on what they find, the district qualifies for a certain number of special-education teachers, what they call teacher units, and that is what drives the request to the Legislature for special-education funding.”

When funding is undercut for special education in public schools, however, the districts have to take money from other places to cover those costs. Loome said it is against the law for public schools to not provide for a child’s needs.

In the case of specialized schools like Magnolia, Loome said that The Parents’ Campaign doesn’t feel like those schools need the funding regardless of the quality of services it may provide students. Though the collaboration between special-needs schools and school districts does work, there should not be a system where public money is sent to private schools, she said.

“There should be a system where all of that money goes through the public schools and is accountable,” Loome said. “And where there are public schools who need to contract with a school like Magnolia to provide services, they can do that. There’s just not a good reason to have a voucher that just flows directly to a private entity that is not accountable to taxpayers.”

Loome said the Legislature has recognized the issues with the voucher program and have made some changes and added some requirements that clear up any loopholes.

“When the bill was first written, it said that private schools did not have to provide any special-education services at all,” she said. “This legislation amended the statute to say that the school does have to provide special education services, that they do have to provide for what is in the child’s IEP.”

‘Eight Kids in a Classroom’

Andrew Bell, 15, is an alumnus of the Magnolia Speech School. He started there when he was 6 years old. When he first began, he said he didn’t even know how to hold a crayon or pencil. But after attending for about two weeks, he improved and started taking writing courses, he said.

“I was diagnosed with auditory processing disorder and dyslexia,” Bell told the Mississippi Free Press.

Auditory processing disorder refers to problems in how a person understands speech, and dyslexia is a learning disorder that involves difficulty learning to interpret or read words, letters and other symbols.

Bell said he had therapy once a week during his three years at the school. He left the school and entered Canton Academy, where he started the third grade and stayed for one year. Bell noted the differences between Magnolia and a more traditional school setting, from the class sizes to the attention from teachers.

“At Magnolia, there’s about eight kids in a classroom, and at a regular school, it’s a lot more. I’ll say about 15 to 20 students, so that’s a big change there,” Bell said. “The teachers at Magnolia spend more time on you than teachers at a regular school. And at Magnolia, we didn’t take tests, but we took them at a regular school.”

The teenager credited the schools he attended for being very accommodating with his learning disability, giving him extra time for state testing, testing him in a room with fewer people and letting him sit closer to the front of the class.

Bell said he is making As and Bs in all of his classes, and he acknowledges Magnolia’s critical role in giving him the tools he needed to earn his current success.

“I think I would be in a lot of after-school tutoring if I had not gone to Magnolia,” he said. “They laid a solid foundation for me to excel in my classes now. It’s been a steady climb, but I am definitely closing the gap. Each year, I get faster at completing my work and tests.”

“I don’t think that any other school could have done for me what Magnolia did for me and others that go there.”

Bell found out about the new facility three years ago when he volunteered at Magnolia for service hours. He thinks the location is in a great spot that offers more visibility and access to help kids get the help they need.

“I think (Magnolia) is a really special place. I think it’ll help a lot of children overcome their disabilities and go far in life,” he attested.

Libba Matthews died in 2016, just shy of reaching 100 years old, Linn shared, but her mission continues, as construction on the new facility should be complete by August 2022, right in time for the next school year. The school is hoping to sell the old facility and has a few buyers in mind, Linn said.

“She was constantly moving around, getting support from the community, so I’m grateful for her and her vision. I’m grateful for this Jackson community, the foundations, people, families and teachers who have helped Magnolia get to this point. … 66 years is pretty impressive,” she said.

For more information about the Magnolia Speech School, visit magnoliaspeechschool.org. To donate to the Building Hope campaign, click here. To learn more about the Parents’ Campaign, click here.