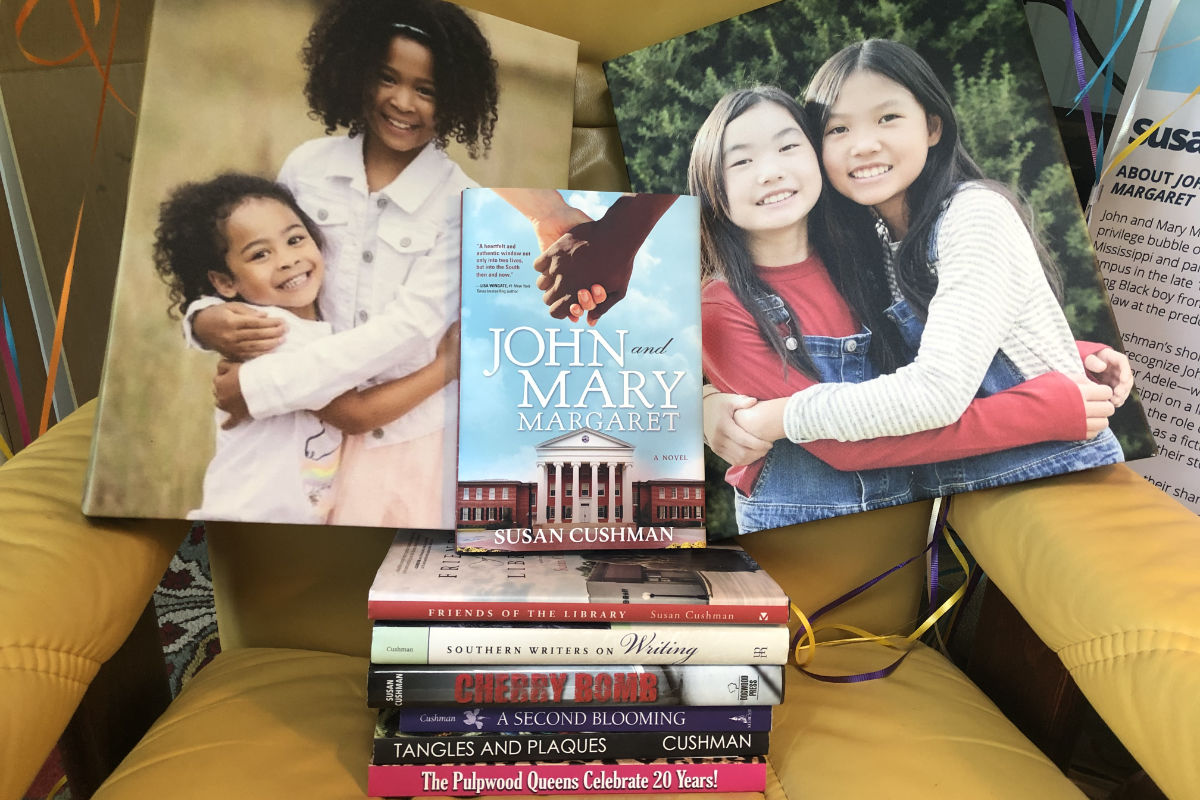

Susan Cushman’s 2021 novel “John and Mary Margaret” relates the coming-of-age story of John, a Black man raised in Memphis, Tenn., and Mary Margaret, a white woman who grew up down the street from Eudora Welty in the Belhaven neighborhood in Jackson, Miss. The pair forge a connection in the crucible of 1960s “Ole Miss,” just a few years removed from the bloody riot over the admission of James Meredith that killed two and wounded more than 300, but societal pressures kept them apart for decades. Cushman’s book explores race, the complexities of interracial relationships and finding love again, against all odds.

The novel, however, does not ignore the pain and near-impossibility of such a relationship in mid-20th century Mississippi. Both Mary Margaret’s and John’s family reject their relationship, though for different reasons: John’s family fears for his safety, while Mary Margaret refuses to share her relationship with her “moderate” white parents out of anxiety over their surely volatile reaction.

John’s family’s fears are well-founded, as he joins a coalition of student dissenters who protest the University of Mississippi’s unequal treatment of its Black students. The group raises the ire of campus administrators, and some are arrested, which is based on an actual mass arrest of members of UM’s Black student union on the campus in 1970. John’s father reminds him of his visions of law school to fight back against the racist society around him, but Cushman makes it plain that the fire of John’s activism is never quenched, only redirected.

Mary Margaret’s family are never painted as overtly racist, never fly any Confederate flags outside their well-kept Belhaven home, but their quiet disapproval of Mary Margaret’s progressive thinking about race relations speaks volumes and gives way to the deepest tension of the novel, tethering Mary Margaret to the possibility of having a comfortable life without the complication of empathy, which would be required for her to carry on her youthful relationship with John, who experiences pain that she never will due to the color of his skin.

The protagonist’s reading of Eudora Welty’s 1963 short story, “Where Is the Voice Coming From,” challenges that sense of comfort, as the vignette was Welty’s response to the assassination of Medgar Evers, told from the point-of-view of his assassin. The piece disquiets Mary Margaret, and the disturbance follows her throughout her young life.

Cushman, though, resists the common urge of southern writers to make saviors out of their white characters and instead allows Mary Margaret to sink back into the complacency that was all too common of the period, disagreeing with the status quo without ever tackling it head-on, a privilege her race and class afforded her.

Mary Margaret, then, returns to her dormant activism in middle age, and her late-blooming regret is the strongest feature of the novel, allowing readers to confront the implications of complacency and choosing another way alongside Mary Margaret. John is the beacon of that nobler path for Mary Margaret, and their love is richer for having been found later. The respect between the pair is palpable, and they talk candidly about what it means to be in love across racial lines.

Middle-aged love is so often passed over in literature in favor of displays of young passion, but Cushman’s portrayal of John and Mary Margaret is convincing, honest and deeply human. The novel arrives at no comfortable conclusions and offers no easy forgiveness for past failures, but it does remind readers of the possibility of change.

Cushman spoke with the Mississippi Free Press in a phone interview from her home in Memphis.

MFP: What was your hope when you wrote “John and Mary Margaret?”

Cushman: I think I hoped for (the book) to do a couple of things, and it’s interesting that you use that word. A couple of people have said that they think the book is full of hope, and that’s my agenda. My agenda is not to be angry but to be hopeful, and to encourage white people like me who thought they weren’t racist to rethink (that notion) with an open and loving heart. I don’t know how many of my readers are Black or white. I actually met with a Black men’s book club recently who had read the book. Being a white woman writing about a white woman and a Black man, I was nervous. They said I nailed it, and that made me feel good.

How did you balance that—being a white woman writing a book that was, in part, about a Black man?

When I was working on the book, I had two Black male authors who gave me early feedback. One of them was the first Black director at NBC, Jeffrey Blount. The other was Ralph Eubanks, who’s actually a visiting professor at (the University of Mississippi). They both read early drafts and gave me a lot of help and feedback.

I wasn’t sure I had the right as a white woman to write this, but Jeffrey (Blount) shared this with me from the Wall Street Journal: “Writers on each side of the color line have more than just the right to cross the divide and report back. It is their duty. Imaginative life depends on cultural exchange. Literature depends on the imagination. To put it another way: Culture is cultural appropriation. Any artist worth the name should be willing to take a punch for it.”

I loved that. That’s what I’m doing. Kathryn Stockett (who wrote “The Help”) did it, and she got pushback and praise. And it goes both ways. Who’s to say that Black people can’t write about white people or Hispanic people or Asian people? “John and Mary Margaret” is a work of fiction, but it was largely inspired by nonfiction. I read Ralph Eubanks’s work, and “Caste” (by Isabel Wilkerson) was super awakening for me. I didn’t read it until I was almost done with “John and Mary Margaret,” but it confirmed the importance of me doing the book.

In the novel, Mary Margaret says, “But we’re not on the plantation here at Ole Miss, are we?” Do you think that was true in the 1960s when she said it? Do you think it’s true at the University of Mississippi now?

I think it was true for her when she said it. I was living in that proverbial white bubble when I was at Ole Miss. I was so unaware of anything going on on campus. I wasn’t aware of the 60 Black students that got arrested for protesting, and Mary Margaret is mirroring my journey. John is challenging her to see it differently. She is becoming more aware. My parents were not racist—whatever that means—but they didn’t know about opportunities to stand up for what was going on. I graduated from Murrah in 1969, and busing and forced integration happened in 1970, so I missed it by one year.

Later in the novel, John tells his wife that they “were on the same team.” Because of that “white bubble,” do you think that would have been true had he married Mary Margaret instead?

I think that they would have struggled in 1970. They each evolved over the next 30 years and found each other again. Mary Margaret’s and John’s whole world would have been turned upside down (had they stayed together). Mary Margaret’s whole family and her friends would have turned against her. I think John and (his first wife) were happy, and I think Mary Margaret settled. She settled for doing the expected thing.

Do you think Mary Margaret’s experience of settling for comfortable activism was common?

Yes. I think we were all expected to marry in a certain social strata and live within the lines of our social situations. People then who were active in the Civil Rights Movement were considered the fringe, the extremists. I think the relationship part of it was really settling.

Because she didn’t continue her relationship with John, she didn’t continue (with her activism). None of the other Tri-Deltas were doing that. She would have had to leave the white bubble to do that, and she would have been the only one. John was willing, but he knew how hard it would be for her and for him, too. He got beaten up for being seen with her on campus.

We see John and Mary Margaret return to Oxford during the novel, despite all the joy and pain that—as you just said—they experienced there. What was the significance of that choice for you?

I think it’s both because of the pain and the joy that they go back to Oxford. She was an aspiring writer, and Oxford is such a literary center. She wanted to be there, and it was a way for John and Mary Margaret to continue to have a voice. Their presence there as an interracial couple was a way to have a voice there. It was another way for them to have a voice and to give back.

Readers can purchase copies of “John and Mary Margaret” on Amazon, at Lemuria Books in Jackson and at Target. Readers can learn more about Susan Cushman by visiting her website.