Rumblings about a serious legislative effort to retire Mississippi’s Confederate-themed 1894 state flag had just begun spreading when members of the Magnolia Bar Association, an organization for Black attorneys in Mississippi that dates back to 1955, received an email.

“I am emailing you to demand the immediate adoption of a new state flag, the Stennis Flag,” Carlos E. Moore, a Grenada municipal judge and attorney at the Cochran Law Firm wrote the bar members on June 9, 2020. “This flag is inclusive to all, as it does not portray the Confederate battle flag.”

Moore explained in his message that Laurin Stennis, the artist who designed the proposed flag in 2014, had asked him to help spread the word and share a petition calling on lawmakers to adopt it as Mississippi’s new banner.

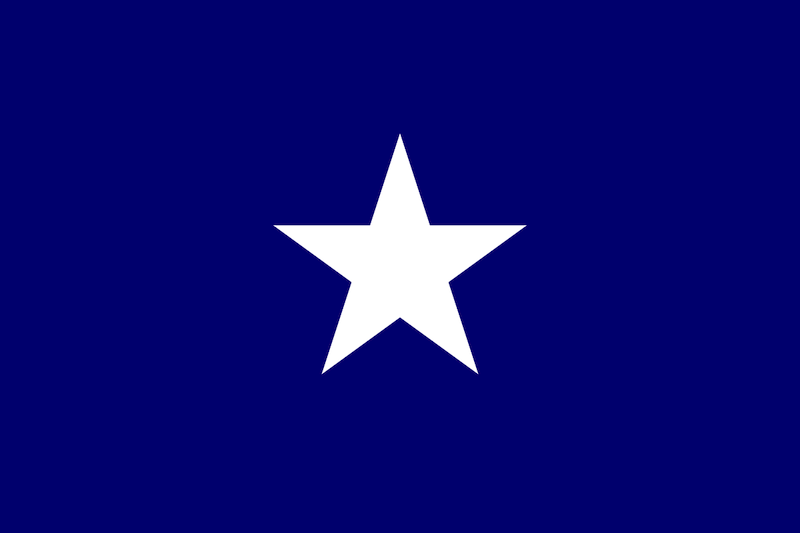

One of the recipients of Moore’s email, Mississippi College School of Law supervising attorney and faculty law instructor Crystal Welch, saw a flaw in the judge’s argument, though. While the Stennis design did not include the Confederate Battle Flag, it did include an ode to the Bonnie Blue Flag, which once served as a symbol of Mississippi’s secession.

The Stennis flag, Welch told Moore in a follow-up email that day, would be “just as problematic as the current state flag.”

“I personally think it looks great, but both flags are Confederate memorabilia, and we can do much better than this to brainstorm a progressive flag that embraces a forward-thinking Mississippi without romanticizing the Confederacy,” Welch told Moore in an email on the same day he asked her to back the Stennis Flag.

Eighteen days after Moore’s email, the Mississippi Legislature voted to change the state flag—but not to the Stennis flag. In the interim, Crystal Welch and others at the Magnolia Bar Association worked quickly behind the scenes to make both those changes happen.

An ‘Inverted Bonnie Blue’

The Stennis Flag, as the once popular proposal for a new flag was informally known, featured a single large blue star set atop a white field at its center with 19 smaller blue encircling it to represent Mississippi’s entry as the 20th state. Laurin Stennis’ design, the flag’s website explained, included red bands on either side to signify “the blood spilled by Mississippians, whether civilian or military, who have honorably given their lives in pursuit of liberty and justice for all.”

By 2020, the design had become popular with Mississippi residents who wanted a new flag, and the Legislature had even approved a license-plate option featuring it.

“With the Stennis flag, it was my understanding that Laurin Stennis created a flag that would reach a compromise between those who wanted to change the flag because they saw the Confederate emblem as racist versus those who saw the Confederate emblem as heritage,” Welch told the Mississippi Free Press on June 30, 2021.

“And so she basically chose an older Confederate emblem, a less offensive and lesser-known one that people don’t associate with the Confederacy as much—one that people in Mississippi might accept as a compromise.”

Stennis had described her flag’s design as an “inverted Bonnie Blue” because the large blue star at the center is an homage to the Bonnie Blue Flag, which features a large white star in its center set atop a blue backdrop.

The Bonnie Blue Flag originally served as the banner of the Republic of West Florida (referring to an area that today is in southeast Louisiana) when residents there rebelled against Spanish rule in 1810 and, later, as a symbol of the Republic of Texas when it declared its independence from Mexico in 1836.

The flag resurfaced again 25 years later at Mississippi’s Secession Convention.

When Bonnie Blue Flew Over Mississippi

Cheers and whooping broke out on the floor of the Mississippi House on Jan. 9, 1861, as spectators in the balcony above lowered a Bonnie Blue Flag down to the delegates who, moments earlier, had approved the state’s ordinance of secession.

That same day, the delegates produced another document: “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi From the Federal Union.”

The declaration explained in its second sentence that the state’s position was “thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.” Mississippi had been given the choice either of “submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union,” the document said. Mississippi—then one of the wealthiest states, if not the wealthiest due to its use of slave labor—chose the latter option.

“These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun,” the document read, citing then-commonly believed myths about racial differences. “These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.”

That night, historian David Sansing later wrote, “residents of Jackson paraded through the streets under the blue banner featuring a single white star.” The Bonnie Blue Flag temporarily flew above the State Capitol dome as a symbol of the state’s declaration of sovereignty in defense of slavery. Singer and playwright Harry McCarthy attended the parade in Jackson, where he found inspiration for his song, “Bonnie Blue Flag.”

“We are a band of brothers, And native to the soil, Fighting for our Liberty, With treasure, blood and toil; And when our rights were threatened, The cry rose near and far Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star,” the song’s lyrics begin. “… As long as the Union was faithful to her trust, like friends and like brothers, kind were we and just; But now when Northern treachery attempts our rights to mar, We hoist on high the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star.”

The song, which McCarthy introduced in Jackson in the spring of 1861, would become the second most popular song in the Confederacy after “Dixie.” In her June 9, 2020, email to Carlos Moore, Crystal Welch cited the lyrics while arguing against the Stennis flag.

In March 1861, the state adopted a white flag that included a magnolia tree at its center and the white Bonnie Blue star in a blue square in its upper left corner. After the Civil War ended and Reconstruction failed, the state adopted a new flag in 1894 based on the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia commanded by Gen. Robert E. Lee. It would live on as the symbol of both the Confederate insurrection as well as “lost cause” mythology, flying atop flagpoles and government buildings in Mississippi until July 2020.

Mississippi Kept Its Flag As Georgia’s Changed

In a vote divided along racial lines, a 63.4% majority of Mississippians declined to adopt a new flag in a 2001 referendum that followed a bruising series of public hearings in which angry white residents often tore into Black members of a governor-appointed flag commission with racist tirades.

“Those hearings back then were very hostile and contentious,” Sen. Hillman Frazier, a Black Democrat from Jackson who was on that commission, told the Mississippi Free Press on June 28, 2021. “You had a very unruly crowd. They were very nasty with very personal attacks, sending out threats and things like that.”

But there were glimmers of hope, the senator said. One young, white woman in the crowd who opposed changing the flag sent him a note after attending a hearing on the coast.

“She was apologizing for some of the behavior of the folks who wanted to retain the old flag. Although she wanted to retain the old flag, she didn’t like the ugliness she saw during those hearings,” Frazier said.

That same year, Georgia retired its state flag, which featured an even more prominent Confederate battle emblem than Mississippi’s. But two years later, 73% of Georgians voted to adopt a new flag based on the First National Flag of the Confederate States of America, with two red bars at the top and bottom, a white bar in the center and a blue canton featuring a ring of white stars. Though less recognizable without the telltale Confederate cross, the new flag was, nevertheless, a Confederate design; it remains Georgia’s flag today.

‘The Flagship Of The Confederacy From 1954 to 1968’

Crystal Welch said she understands the thinking behind the Stennis flag including an ode to the Bonnie Flag. But if Mississippi was going to change its flag in 2020, amid an unfolding national reckoning on race, then the Magnolia State could do better than such a compromise, she said.

“To me, I find that compromising on issues of race never indicate the sort of progress we want to take place in a state like Mississippi,” Welch told the Mississippi Free Press on June 30. “And to compromise like that in terms of swapping one Confederate emblem out for another, it would really communicate to me that we hadn’t done anything. So I really felt deeply that the Bonnie Blue emblem was almost as offensive as the Confederate cross.”

Some opponents of the Stennis Flag, though, had a different issue: they did not like its association with Laurin Stennis’ grandfather, former U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis, who served in the Senate for 41 years. Once an avowed segregationist and a signer of the infamous Southern Manifesto, Stennis rejected his former views before his death in 1995. Though he had been an opponent of the 1965 Voting Rights Act at its inception, he voted for its reauthorization in 1982.

As a young U.S. senator in 1970s, Joe Biden developed close relationships with Sen. Stennis and Mississippi’s other Dixiecrat senator at the time, James Eastland. In 2008, Biden told then-Jackson Free Press editor Donna Ladd, who is now this publication’s editor and co-founder, about one of his last meetings with Stennis before the old senator retired.

“You see this table and this chair? This table was the flagship of the Confederacy from 1954 to 1968,” Biden recalled Sen. Stennis saying as he placed his hand on the table in his office. “This table was the flagship of the Confederacy from 1954 to 1968. Senator (Richard B.) Russell had (representatives from) the Confederate states sit here every Tuesday to plan the demise of the Civil Rights Movement. We lost, and it’s good we lost.”

Biden recalled feeling chills as the longtime Mississippi senator continued.

“It’s time this table goes from the possession of a man against civil rights to a man for civil rights. … The Civil Rights Movement did more to free the white man than the Black man,” Stennis said. When Biden asked what he meant, Stennis answered: “It freed my soul.”

‘A Community Of Voices’

Crystal Welch said Laurin Stennis’ family history was never an issue for her.

“I do understand that a lot of people had an issue with Laurin’s relationship to her grandfather, and a lot of people felt that the new flag did not need to be tainted with the legacy of a family that once fought so hard for white supremacy, but I personally did not agree with that position. People can change and grow,” Welch said.

“But I don’t think her voice represented the diversity of voices in Mississippi, and it was always my position that our flag should be the result of a community of voices who made that decision.”

After Moore’s email, Welch shared her concerns about the Stennis flag in a Facebook discussion, and Alicia Hall, a white Jackson attorney and former classmate of hers from Jackson, offered to help.

Welch contacted Sen. Hillman Frazier, the 2001 flag commission member. After she explained her opposition to the Stennis flag, the senator told her that a group of mostly Black Democratic lawmakers were drafting a legislative proposal to adopt it as the new state banner. Frazier arranged for Welch and Hall to meet with them.

The bill was mere minutes away from heading to committee for consideration when the attorneys arrived for the meeting mere days after Welch first raised her concerns with the Stennis flag in response to Judge Moore’s email.

“They gave us a couple of hours and said, ‘Hey, if you submit a new flag design in the next couple of hours, we’ll submit that (instead),’” Welch recalled.

Welch contacted Rocky Vaughn, a white Starkville-based artist who had previously designed a flag concept featuring a magnolia at its center, and asked if she could offer his design.

“The magnolia was more of a symbol of who we are as a state than the Stennis Flag, and I thought it was something most Mississippians could identify with, and I think a lot of Mississippians were familiar with Rocky’s design from years before when there was a Clarion-Ledger contest,” Welch said. “He was one of many artists that had submitted a design, and he suggested we use the flower. And it was the better-looking and most aesthetically pleasing.”

In their proposal in mid-June 2020, Welch and Hall asked the legislators not to vote on any particular flag, yet.

“We asked them to actually devise a committee that would invite a vexillologist to study the iconography of our state and incorporate that into a new flag design and let people vote on it,” Welch told the Mississippi Free Press.

“And we ended up contacting several people who were active in the process and asking them not to support the Stennis Flag and asking them to make sure that they supported a more celebratory flag that would be something that the majority of Mississippians could relate to. And the more that we had that conversation with people, the more they were receptive. And we saw that more people began to back away from the Stennis flag.”

‘There Was A Shift in Mississippi’

When Laurin Stennis first offered her flag design in 2014, which she officially titled the “Declare Mississippi Flag,” she explained that her mission was to craft “an image that would better capture our history and hopes without denying or romanticizing our past.”

At the time, no prominent Republicans had supported changing the flag. Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn, who would later back a change following the 2015 Charleston church massacre of Black worshipers, offered no comment when the Clarion-Ledger asked him about it that year. Even after Gunn announced his support for it, few other influential lawmakers joined him. As the Stennis Flag became more common, some lawmakers and residents who wanted a new flag saw it as the most politically viable option despite its compromises.

But 2020 changed the calculus, Welch told the Mississippi Free Press.

“I believe there was a shift in Mississippi. People in the past had assumed the flag issue was about politics. At this point, it became more about morality, right versus wrong, and I think we owe that to George Floyd causing a shift in the atmosphere in which people began to rethink race relations in the U.S. and in Mississippi in particular,” Welch said. “And last year, people who were traditionally in favor of the Confederate emblem on the flag began to rethink the consequences.”

In the weeks before the flag vote, Welch said she and others from the Magnolia Bar Association worked to convince Republican lawmakers to publicly support the effort. She had heard that Speaker Gunn and Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann, the Republican Senate president, both backed moving forward on changing the flag, though with some wrangling over whether to do it legislatively or by voter referendum. But few other Republicans in the House or Senate had yet spoken out in favor of a new flag.

“When we would talk to Republicans one-on-one, they would say, ‘We would love to take this into consideration, thank you for this information.’ But none of them had really committed,” Welch said. “They were very polite and were willing to take the time out to discuss it, but they were non-committal at that point.”

Then-Sen. Sally Doty, a Lincoln County Republican who has since left the Legislature, was one of the lawmakers the attorneys sought to persuade. But in 2001, Lincoln County had shown even more resistance to changing the state flag than the state as a whole, with nearly 75% of residents there voting to keep the old one.

Doty’s predecessor in Senate District 39, then-Democratic Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (now a Republican U.S. senator), was a reliably conservative Democrat when she served from 2000 until 2012. In 2001, Hyde-Smith, a segregation academy graduate, even proposed a bill that would have renamed a section of highway for Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Senate District 39 remains a conservative stronghold. After the 2015 Charleston church shooting, Doty declined to take a public position on changing the flag, calling it an “emotional” issue, but saying that she would be open to “a conversation” about it. Welch said Doty still felt reluctant to publicly back changing the flag in the weeks before the vote.

But Doty ultimately decided to support changing the state flag, telling the Daily Leader that, after “many conversations” with constituents, she had become “convinced that our flag was truly hurtful to my brothers and sisters in Christ.”

“She was just not willing to betray her constituents, but she felt the conflict, and it was very obvious she wanted to do the right thing, and I’m very proud of her,” Welch told the Mississippi Free Press last week.

‘The Perfect Storm’

On June 19, 2020, 10 days after Carlos Moore’s email, the Magnolia Bar Association issued a press release endorsing the effort to change the state flag—but opposing the Stennis flag design.

“The Magnolia Bar Association commends and fully supports the progress our state has made, but as a body, we are not convinced the Stennis Flag will bring the promise of hope, healing, and future that we desperately need,” the statement read. “… And while the designer is undoubtedly well-intentioned, the design bears strange resemblance to the Bonnie Blue Flag—yet another Confederate symbol—and carries the name of Senator Stennis.”

The letter called for the Legislature to “establish a commission of legislators to select a new state flag,” allow local artists to submit designs and for the Mississippi Black Legislative Caucus to work with Republican leaders to pass bipartisan legislation for a new flag.

On June 21, Laurin Stennis announced that she was stepping down from the campaign for the “Stennis Flag”—a name she had never used for it herself but which had become its popular title. She suggested rebranding it the “hospitality flag.”

But even as hopes for adopting the Stennis flag were fading, the floodgates opened for the overall effort to select a new flag as college athletes, business leaders and religious leaders, including the Mississippi Baptist Convention, all aligned in favor of a change. Those developments came on the heels of the largest protest in Mississippi history since the civil rights era.

Earlier that month, following an interracial “BLM Sipp” march in Jackson that included thousands of Mississippians on June 6, 2020, Black activists had read aloud a list of demands for change in Mississippi—including, among other items, a demand for changes in policing, criminal-justice reforms and the adoption of a new state flag.

“And together you just have the perfect storm—against the backdrop of a pandemic with tons of people flooding the streets in support of George Floyd and his family—for Mississippi to rethink our race relations. And our approach in changing the flag reflected that,” Welch said.

After legislative leaders proposed requiring the new flag design to include “In God We Trust,” words already featured on the Mississippi state seal, more Republicans began publicly endorsing the push for a new flag.

“I think that the ‘In God We Trust’ compromise was one of the factors that convinced some of the more conservative legislators to get onboard. It was almost a quid pro quo arrangement,” Welch said.

‘Folks Had More of an Open Mind’

Unlike 2001, Sen. Frazier told the Mississippi Free Press, “folks had more of an open mind” during debates over the flag in 2020. Just as he saw a glimmer of hope in a young woman’s apology for the behavior of other 1894 flag supporters back then, he saw hope for the future in the efforts of young activists in 2020.

“All of them came together and showed us where we can go together,” he said.

On June 28, 2020, the House and Senate overwhelmingly voted to retire the 1894 state flag. The bill followed Welch and Hall’s earlier suggestion to establish a commission to select a new state flag design and allow voters to either approve or reject it in a November referendum.

Once the flag commission began its work, Welch offered feedback and suggestions.

“I even proposed that they accept Rocky Vaughn’s magnolia graphic for our new flag design,” Welch said. “They took all of our considerations very seriously. And when it was all over, I did get an email thanking me for the emails I sent them, and they stated that it was persuasive and very well thought out and that they appreciated my feedback.”

On Sept. 2, the Commission to Redesign the Mississippi State Flag announced its final pick: an updated version of Vaughn’s design that Welch and Hall had originally pitched to lawmakers on June 9, 2020, with design support provided by Sue Anna Joe, Kara Giles and Dominique Pugh. Like Stennis’ flag, the proposal featured red bars. But instead of an inverted Bonnie Blue Star at its center, Vaughn’s featured a magnolia on a blue field encircled by stars. It also incorporated an element from the runner-up flag designed by Micah Whitson: a diamondhead star at the top of the circle to represent Mississippi’s indigenous tribes.

“The New Magnolia flag is anchored in the center field by a clean and modern Magnolia blossom, a symbol long-used to represent our state and the hospitality of our citizens,” the Mississippi Department of Archives and History said in a statement on Sept. 2, 2020. “The New Magnolia also represents Mississippi’s sense of hope and rebirth, as the Magnolia often blooms more than once and has a long blooming season. The New Magnolia is sleek and updated to represent the forward progression of Mississippi.”

Exactly two months later, 73% of Mississippians voted to approve Vaughn’s design as the new state flag. Crystal Welch’s quest to ensure the new flag would tell the story of Mississippi’s diversity and progress had succeeded.

“We ended up with the flag that I think the majority of Mississippians are proud to have represent us,” Welch said.

Read the MFP’s full series on how the Mississippi flag finally changed in 2020:

1. Black Mississippians Paved The Way For State Flag Change A Year Ago Today

2. ‘No Compromise’: How Crystal Welch Changed The State Flag Debate In 19 Days

3. Young Black Activists Helped Change The State Flag. They Intend To Change The State.

Also see: The Flag and the Fury (Radio Lab Podcast)