Derick Mercadel is no stranger to water pains: the pain of too little and the pain of too much. Mercadel originally hails from St. Bernard’s Parish, near New Orleans. The resident of south Jackson recalls braving Hurricane Katrina in 2005 until the totality of flooding and devastation around his home parish forced him to temporarily relocate to a shelter in Benton County in Mississippi.

“I remember I was on a block with two neighbors,” Mercadel said. “We decided to stay behind because in Algiers it wasn’t bad flooding on the west bank, but we had no power. So we just decided to sit out there and barbecue all our meat; then you have the National Guard coming around telling us to go inside. I was like, we’re not going in this house, it’s too hot to go inside,” he told the Mississippi Free Press in a June interview.

Mercadel has experience with social breakdown. In the days following the hurricane, even the police were left scrambling for supplies, Mercadel recollects.

“I remember going to Walgreens, and we were going to just take any supplies we needed to survive, but we had to wait for the police,” Mercadel said. “ The police said, ‘We’re in here right now, y’all wait until we finish.’ (They) went in there and got what they needed, then after they left, we went in and got what we needed.”

“That’s just how it was,” he said. “That’s the stuff you’re not going to see on the news.”

Now permanently relocated to Mississippi, Mercadel’s water pains continue. In the aftermath of February’s winter storm, Mercadel lost access to water for two and a half months. His house was connected to well water, the one water system serving the City of Jackson that did not see significant outages during the winter storm. But the hard freeze damaged many pipes at homes and apartments across the city, leaving individual homes and customers without water even as their connections were repaired.

Though Mercadel’s water eventually returned, it wasn’t the end. Beginning on May 18, Mercadel lost access to water for three days, had low pressure for two weeks and unsafe drinking water for over a month at his Maddox Road home. It was a miserable continuation of the Jackson water crisis not much easier to endure than the city-wide outages of February and March.

The culprit? Two broken water pumps in the Maddox well system, struggling with lingering maintenance issues from previous failures. The month without safe water revealed fractures for Mercadel, too—yet another wearisome burden, piled on top of years of crumbling infrastructure in south Jackson.

“We’ve got buckets on standby,” he said. “That’s sad, man. I keep a bunch of buckets. I don’t have that many now ‘cause you lose them, some people borrow them, you don’t get them back, but I try to keep at least 10 buckets around and when I see that pressure going low, I start filling my buckets up.”

Months Without Water

In 2009, Mercadel and his now wife moved to Jackson, her hometown, where they made their home on Maddox Road. Water trouble followed them, Mercadel said, and for the past 11 years they have been unceasing.

“(My wife) said that they never used to have problems, the water like this, but since I’ve been staying here—every year, we get low pressure or no pressure.”

Mercadel estimates that they receive city-issued boil-water notices about every two months, and that it isn’t always easy to know they’ve been issued.

“You wonder why, why do we have to boil water so much,” Mercadel said. “What’s really going on with that?” The pace of the crises, one after another, robs Mercadel of even the basic comforts of modern life. In 2021, the catastrophe only grew.

Mercadel’s water problems compounded this year with Jackson’s historic winter storm, leaving him without water for two and a half months. “That was horrible,” he said. “It started probably the first week of the ice storm, and it lasted at least until about April.”

“I was outside cutting up ice and putting it in my tub to melt it,” Mercadel said. “I would boil some and melt it to dissolve the other ice that I had sitting in the tub. “It’s miserable to live like this, and this is the United States of America, you know?”

Now, months later, Mercadel is hopefully at the end of his catastrophic months without water, but he still laments what he perceives as Jackson’s lack of response to his and his neighbors’ plight.

“You have to buy gallons of water to wash and brush your teeth, but there’s not even a rebate for us as far as the money we spend on water when we have no water coming out of the ground,” he said.

”Do you really care about us? You’re not even trying to give us our money back. That’s piss-poor customer service. You go to a restaurant, and you’re waiting long for your food, they’ll at least offer you a free drink,” he said. But a free drink in a city without water is hard to come by. The city is in the process of addressing extant bills to customers who lacked water access at the time.

As the winter storm subsided and workers repaired damaged infrastructure, Mercadel had about two weeks of normal water usage until disaster struck again. This time, a number of parts in the TV and Siwell Road pump systems failed, taking the systems offline and once again removing Mercadel’s access to clean and safe water.

A Second Tap

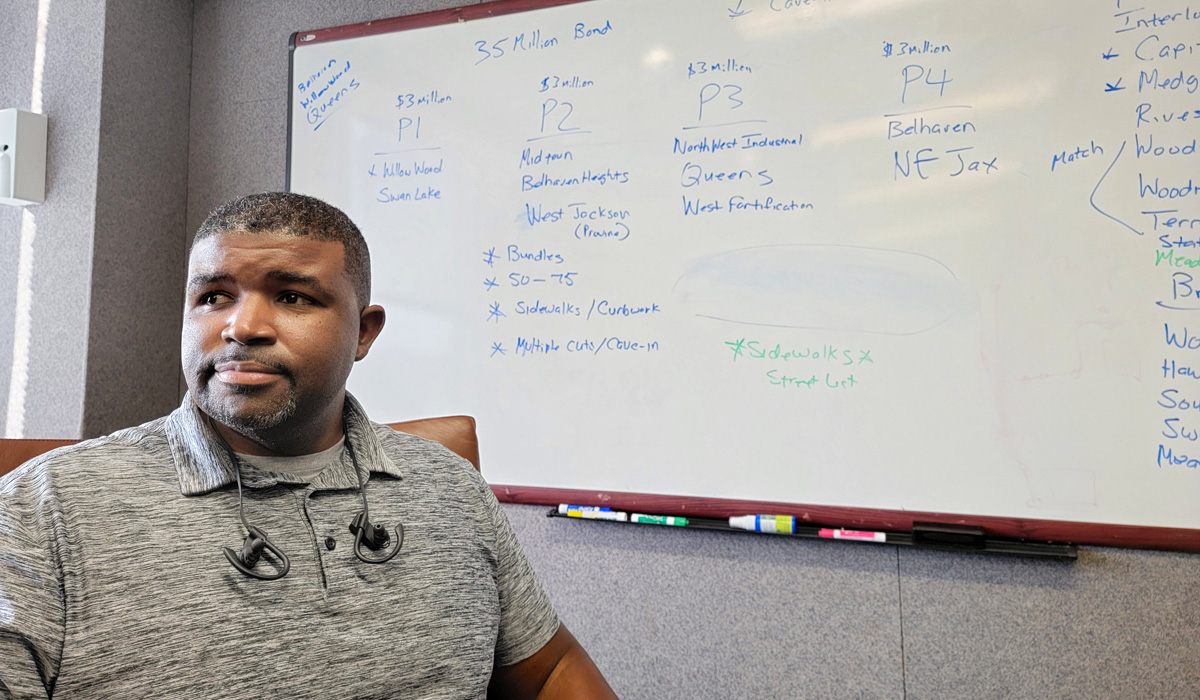

Jackson Public Works Director Dr. Charles Williams addressed the problem in a press briefing later that day, explaining how the repair process would work and giving a hopeful timetable.

“We’re basically assessing the situation while the contractor is outside and starting to break the well down and determine the actual cause of that failure,” Williams said on May 18, the day of the incident. “We also anticipate having a mitigation plan in place that we can quickly make the repair in order to have water restored to that area off of Siwell Road by Friday, and then we will look at TV Road, and that will be the best case scenario.”

That best-case scenario did not pan out for about 2,000 south Jackson residents, including Mercadel. Though he regained some amount of water pressure three days later, the temporary pump city officials installed gave only low pressure, and what water it did provide was unsafe to drink. This situation lasted until June 24, when Jackson officials lifted the boil-water notice.

On May 18, the day of the pump failure, Mayor Lumumba spoke to the public asking for their patience and understanding.

“I’d like to thank our residents for their patience once again,” Lumumba said. “We know how difficult it is. We know what a sacrifice and challenge it is to go without water not only for drinking, but for bathing and for sanitary purposes. Our hearts go out to those residents,” he said.

Lumumba went on to describe the state of the city’s infrastructure, and how incidents like these will continue until more funding flows into city coffers.

“I believe that the city of Jackson is still in the midst of a crisis because of our aged infrastructure, our legacy city. Until it is addressed, until we can comprehensively and effectively address it with the appropriate resources to accomplish that feat, we will continue to fight with this system,” Lumumba said.

The mayor mentioned the billions of dollars attached to fixing Jackson’s infrastructure problems, a number he calls a “conservative estimate.”

“That’s before we get to drinking water, that’s before we get to storm water, that’s before we get to roads and bridges,” Lumumba said. “And so that is at best a conservative estimate as to what our problem really looks like.”

The infrastructure burden facing legacy cities like Jackson is real—a symptom of years of disinvestment at the local and federal level. Nationally, President Joe Biden has promised tens of billions of dollars in water infrastructure investment as a part of his grand infrastructure plan, but such an investment must survive a hostile Congress before it can arrive in a place like Jackson.

Legal Action Possible?

In a July interview with the Mississippi Free Press, Dr. Williams confirmed that most residents should have only experienced one of the two manifestations of the Jackson water crisis this year. Those who lost their well water would not have lost surface water connection after the winter storm and vice versa, even if individual consumers could have experienced significant damage to their home pipes and thus their water access.

Williams laid the blame for the well outages at the feet of the contractor who completed repairs on the system last year. “We had some issues last year with both wells, around July, and late September and October,” Williams said. “We had a contractor come in and assist us with both repairs. This year, around April and May, we started seeing some vibrations in both wells that ultimately turned into issues that caused us to take both wells offline.”

Adequate repairs could have avoided those lingering issues, Williams asserted. “To be very general, it looks like the previous work performed was not up to standard, resulting in a pump failure at both locations. We had to replace pumps, pipeshaft and tubing,” he said.

The public works director declined to name the contractor responsible for the 2020 repairs he says caused this year’s well outages. In part, this is because the city is still mulling over possible legal action against the contractor in question.

“Our preliminary conclusion is that the work that was performed on the two wells was not up to par,” Williams said. “We’re getting all of our information to review with our legal team to determine what will be the next step. Right now our goal is getting all of the wells back in operation.”

That part of the task is nearing completion. Currently, all six of the permanent well pumps are in place and repaired. As of Tuesday, July 6, the Mississippi State Department of Health is sampling the newly installed TV Road pump: safe samples will mark an end to this chapter of the Jackson water crisis.

Jackson’s own legal proceedings continued this month as well, with the City entering into an Administrative Order of Consent with the Environmental Protection Agency, the beginning of a renewed process to bring Jackson’s public water utilities in line with the Safe Drinking Water Act. The order includes the many deficiencies the EPA identified in last year’s inspection of the city’s two water treatment plants.

The order of consent is merely the prelude to the work ahead of the city. “There is an order, signed by both sides, committing to that work,” Williams said. “Now the work really begins: we’ll send information to them over the next 30 to 60 days. There’ll be further discussions and evaluations of timelines and costs.”

The job ahead is immense, and Williams acknowledged that the city’s public-works leadership was eagerly awaiting the outcome of the infrastructure plan that Congress now debates—the only realistic source of the massive funding that Jackson’s crumbling infrastructure requires.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do,” Williams said. “And we’re committed to doing it.”

The Wellspring of Inequality

Still, Mercadel is deeply frustrated with the city’s leadership.

“The solution is simple,” Mercadel said. “You raise money, and you fix it. You replace it. You don’t wait until everything goes to hell and then get on the news and say that you’re working on it. That’s what we did in New Orleans with the pumps, because of the flooding. They knew that they had to replace the pumps, so they raised money and they started replacing pumps before hurricane season.”

“Do you really care?” he asked of Lumumba. “You’re not coming up with solutions.” Mercadel said failing to meet with a rival during a crisis over politics, “is a bad example of a leader who cares about the people who put him in office.”

Though a conversation with the governor never materialized, Lumumba has since met with Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton. The meetings came at the height of tension between state and city leadership over who bore responsibility for Jackson’s lingering water issues.

Mercadel sees the tension between city and state government as counterproductive to helping Jackson when inequality in Jackson runs rampant.

“I deliver groceries at Whole Foods, and I could not believe that in walking distance from some of the poorest parts of Jackson are mansions,” he said. “Then you ride five minutes in a different direction, and you got poverty everywhere, and the poverty is accepted because it’s just a way of life for America—to make sure that that wealth inequality remains that way.”

Mercadel sees Jackson’s water problems as inexorably linked with inequality.

“These rich neighborhoods I go to, I never see them having problems with their water. “But you’re still in the same city, you’ve got the same mayor. You’ve got the same mayor.”

Mercadel carries the memory of inequality and racism from Louisiana, where for a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s he worked around New Orleans. At the same time, none other than ex-Grand Wizard David Duke of the Ku Klux Klan was serving a single term as a Louisiana state representative. Police would regularly stop Mercadel, who delivered papers at the time, though the man did everything he could to make his car bright, visible and inconspicuous.

“I would get pulled over, get out of the car, stand handcuffed while they searched my car, every night,” Mercadel said. “I stopped delivering papers.”

Now Mercadel, who served from 1989 to 1993 in the Louisiana National Guard and honorably discharged as a specialist, thinks an inclusive political process rather than partisan bickering would better serve the poorest and most vulnerable in Jackson.

“I just think that if we had a governor and mayor who could tolerate sitting down just having lunch, I think a lot could get done,” Mercadel said. “They can’t even sit down there and have a Whopper. Now if you can’t sit down and have a Whopper with somebody, you’ve got problems.”