There are two ways to win an election in America. One is the standard that viable democracies use around the world: convince a majority to vote for your candidate.

The second rests on sinister trickery: keep the voters who oppose you from the ballot box. This also happens to be the favorite tactic of quasi-democratic authoritarian republics like Honduras and Turkey. Journalists and academics use the anodyne phrase “voter suppression” for this grab-bag of nefarious anti-democratic techniques.

Back in the day voter suppression was straightforward in my home state of Mississippi—such as a deadly shotgun blast. In this case, the sheriff of Amite County was the one holding the smoking shotgun. The offense his victim Louis Allen committed? Registering to vote, and seeing a white man kill a Black man.

Mississippi legislator E.H. Hurst had fired a shot into the head of Herbert Lee, who was organizing voting drives for Black residents. Hurst was acquitted of Lee’s murder because white Mississippi juries knew that “voting while Black” was the real crime.

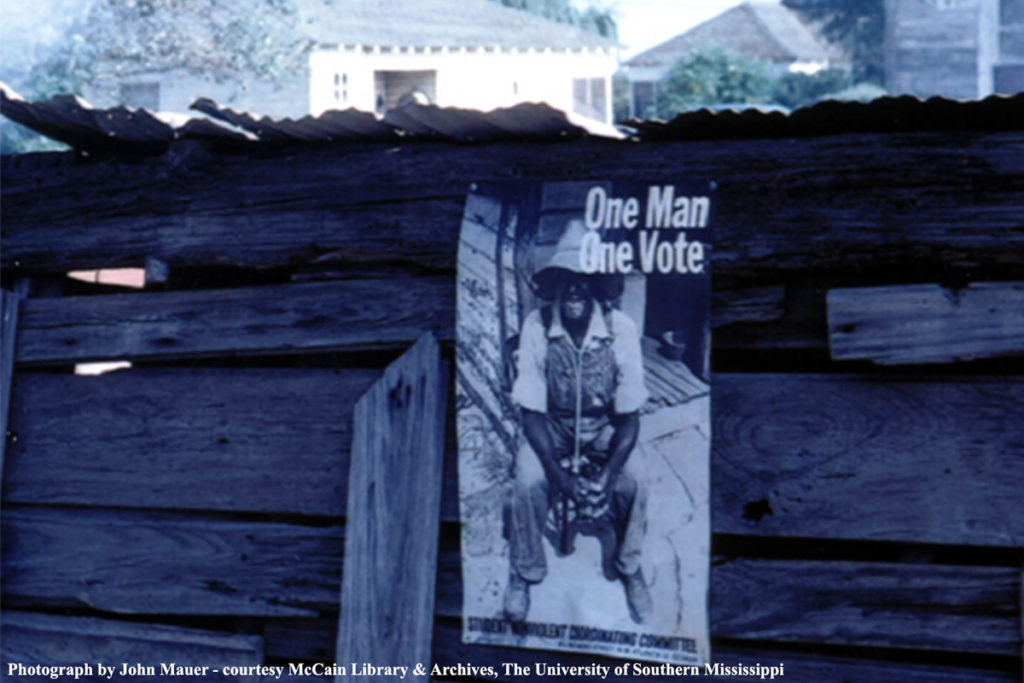

Both these “voter suppression” murders took place in the ironically named Liberty, Miss. SNCC organizer Bob Moses was trying to change Liberty then by registering Black Mississippians to vote. SNCC is the acronym for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—among the most important of the four civil-rights organizations operating in Mississippi in the 1960s.

Unita Blackwell lived a few hours away from Liberty, up Highway 61 through the Delta. The Movement came to her town soon after Lee and Allen were murdered. People were scared to get involved because voting could mean death; everyone knew that. The SNCC organizers showed up at her church one Sunday, looking for volunteers to register to vote.

I interviewed Ms. Blackwell about it in 1997. This is what she told me:

“And he said to us, we had a right to register to vote. And something hit me inside — of agreement. I knew it was something wrong. I just knew it. I been knowing it ever since I was a child. And it made the connection, that if you register to vote, you have a better house to stay in. And the one I was staying in, right across over the road there, was falling apart. And I could connect it, what it meant to me. What it really meant to me and my family. And your child could be educated. And I was thinking about struggle that my mother had been through, and my father and family trying to just get us to what we called the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic ….”

He told us that next week—who would stand up and say they would go to try and register to vote. And I was one of those people that stood up. … I stood up, and I been standing up ever since. Fighting for freedom.

I made a short film about what happened next. “If I die, I die for something. Nothing for nothing leaves nothing. We didn’t have nothing, so I was going to try to see could I get something. One of those things was my right to register to vote and to become a citizen of these United States,” Unita Blackwell told me.

I know this story from the white side of Mississippi since I grew up there during the Civil Rights Movement. I was born a week after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision that school segregation was unconstitutional. Yet my school, Oxford High School, wasn’t integrated until I was 16 years old in February 1970 since Mississippi had its own peculiar interpretation of “all deliberate speed.” I saw what comes of “voter suppression,” and how it subverts both democracy and good government.

I grew up with the results: poor quality schooling for white and Black students alike, with lack schools failing to meet even the most minimal level. Corrupt contractors working for highway commissioners on the take build our substandard roads and bridges. Our economy sat at the bottom of the nation. Young people fled the state in droves as soon as they came of age; unless you were a paid-up member of the good ol’ boys club, prospects were limited for Black and white Mississippians alike.

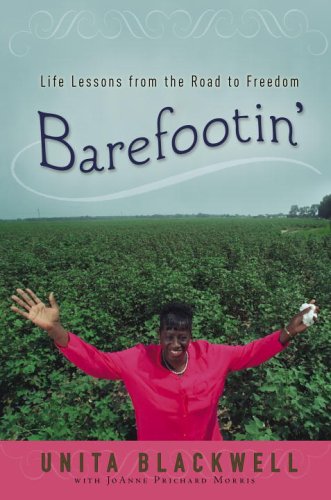

Unita Blackwell was one of the heroes who joined SNCC and brought the vote to Mississippi, courtesy of the Voting Rights Act. Its passage by Congress in 1965 was bought with the blood of martyrs and the untold suffering of thousands more. Ms. Blackwell and hundreds of thousands of Black Mississippians changed my state with their votes.

In the 1970s she became mayor of Mayersville, where she paved the streets, built parks and public housing, and installed the first sewage and water systems its residents had seen. It was a happy ending to a long struggle. She died in Biloxi in 2019.

A New Era of Voter Suppression

But the fight for democracy is never over; complacency leads to decay of the institutions and laws that protect our vote. In 2013 the Supreme Court disemboweled the Voting Rights Act, ushering in a new era of voter suppression.

Mississippi history taught me that attacks on voting get bigger and bolder as time goes by—don’t forget that Black Mississippi men got the vote just after the Civil War and used it over the next 20 years to create public education and social-welfare legislation that helped build Black communities and free the state from the worst of its slave legacy. It was this Black success in voting that spawned a counter-revolution of violence, fraud and eventual disenfranchisement under the segregationist 1890 Mississippi Constitution. Now the same backlash against voting is happening again.

Today’s GOP is filled with white southerners of my generation who remember the “good ole days.” People like Mitch McConnell grew up in 1940s and 1950s Alabama and Georgia where things were just as bad as Mississippi. Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again,” is a window to the past, clear as glass to his followers. It should surprise no one that today’s GOP is trying to hang onto power by limiting the votes of its opponents.

The words of Unita Blackwell are just as true now as they were in the 1960s: “But I think what hit me again, inside of me. That this must really be something. It must be really something when they see these people come with guns, to defend. To keep us down, from this. Registering to vote. This vote must really be about something.”

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.