The UM Emails

Part I • Part II • Part III

This is Part II of a three-part investigative package.

On the evening of April 18, 1983, fear gripped 20-year-old African American University of Mississippi student Danny Love as he hid with his fraternity brothers inside the Phi Beta Sigma house. Around a thousand white students had marched across campus and descended upon the predominantly Black fraternity house chanting “Save the Flag,” referring to the Confederate flag, and singing “Dixie.”

“I wish I was in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten, look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land,” the mob sang.

It was Dixie Week, the university’s annual seven-day celebration of the school’s Old South heritage. But the unofficial anthem of the Confederacy was not all that the Black students huddled in the house heard that evening. Members of the white throng surrounding the only Black fraternity house on campus were also screaming, “N*gger,” Love told a United Press International reporter in May 1983.

“I was afraid. We knew they were capable of breaking into the house,” the 20-year-old from Coldwater, Miss., told UPI.

The rampaging white crowd had heard rumors that Black students planned to burn copies of the 1983 yearbook over its inclusion of photographs of a Ku Klux Klan march on campus during the prior year. That book burning never materialized, and neither did violence after police peacefully confronted the white mob that evening.

When the UPI reporter asked then-UM Director of Public Relations Ed Meek about that evening’s events, he was dismissive.

“It was nothing but a spring pep rally,” Meek said, looking the reporter straight in the eye.

As a student photojournalist two decades earlier in 1962, Meek had witnessed the “Battle of Ole Miss,” a deadly confrontation that erupted on campus as thousands of angry whites rioted over James Meredith’s admission as the university’s first Black student, prompting President John F. Kennedy to dispatch federal soldiers and members of the Mississippi National Guard to Oxford to quell the uproar. Still, two people were killed, and hundreds sustained injuries.

“Perhaps it was only a (spring pep rally) to a man who has the perspective of Meek, a member of the Class of 1962,” the reporter mused in the 1983 UPI story. For many Black students, though, it was a stark reminder of how near that history remained.

The frightful night was part of a series of events that 19-year-old cheerleader John Hawkins, the first African American on the squad, had set into motion the previous fall when he refused to carry the Confederate flag onto the football field.

‘The Stirring Strings of Dixie’

Back then, the seas of Rebel flags that characterized UM football games and annual traditions like Dixie Week were only a few decades old. They arose as part of the South’s response to the burgeoning national embrace of civil rights in the mid-20th century. In 1948, Democratic President Harry Truman signed an executive order desegregating the military, and the national party backed a strong civil-rights platform, creating a rift with racist Democrats in the South.

Segregationist South Carolina U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, a Democrat, launched a third-party presidential run that year as a member of the States’ Rights Democratic Party, also known as the Dixiecrats. For his running mate, Thurmond chose Mississippi Gov. Fielding Wright, a fellow opponent of civil rights. When the Dixiecrats held their convention in Birmingham, Ala., that summer, 55 UM students left Oxford in an 11-car caravan to attend, historian David Sansing recounted in his 1999 book, “The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History.”

The protest campaign won a majority of votes in just four states, including Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. Years later, Thurmond switched to the Republican Party alongside other Dixiecrats.

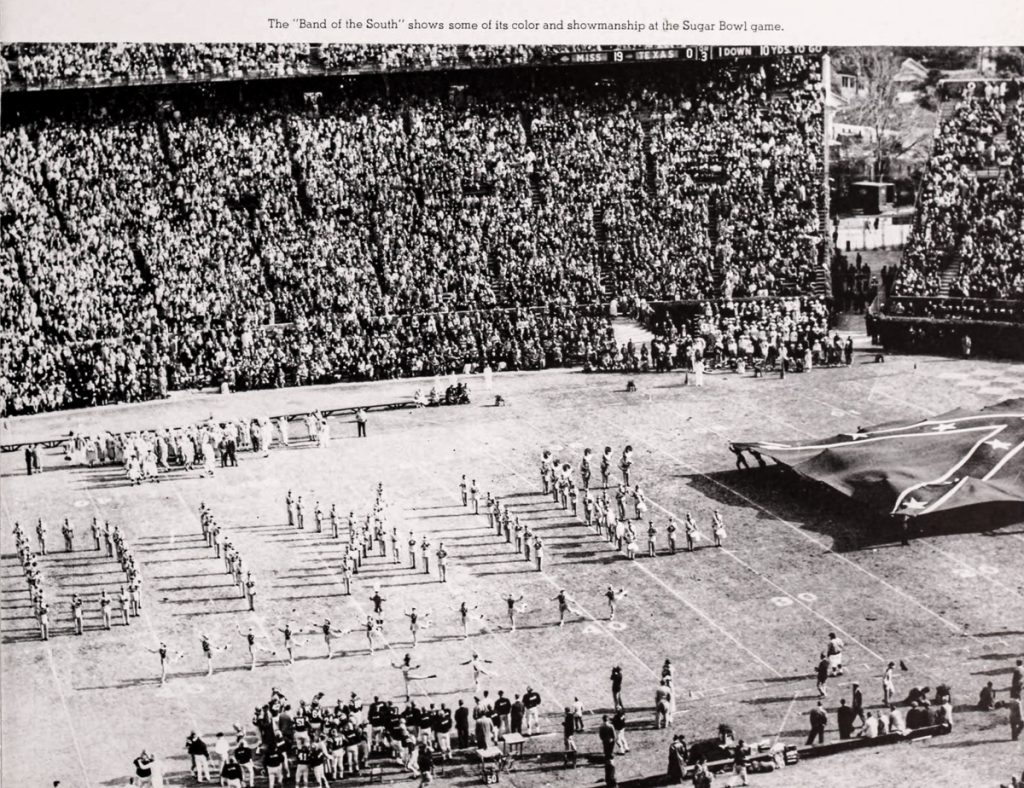

The 1948 campaign was a part of a rising tide of southern “mass resistance” to integration and civil rights in the South. Across the region, white resisters embraced the Confederate Battle Flag as a symbol of their 20th-century southern cause. That fall, the UM band marched onto the football field at halftime and, for the first time, presented a show that would become a school staple for decades.

“In 1948, the Ole Miss band introduced a wildly popular halftime routine during which it marched onto the field unfurling the world’s largest Confederate flag to the stirring strings of Dixie,” UM historian David Sansing wrote in his 1999 book on UM’s history. “The 1948 M-Book explained to new students that the giant Rebel flag did not mean that Ole Miss was not in the United States. It meant they did not want anyone telling them what to do.”

The symbols of the Lost Cause “were woven into the fabric of student life at Ole Miss” by the early 1950s, Sansing wrote, noting that UM inaugurated Dixie Week in November 1950, with the student body president reading the Ordinance of Secession from the student union balcony. (The ordinance is less straightforward about Mississippi’s reasons for seceding than its Declaration of Secession, which directly identifies support for slavery as the root issue.)

John Hawkins’ defiance of those traditions 32 years later set off a chain reaction, leading some people across the state to question not only the continued use of the Confederate flag, but even the Mississippi state flag, with its iconic Rebel image in the canton. White robed klansmen, angry over the turn of events, then marched onto the campus in protest in fall 1982.

As the school’s spokesman, Meek found himself spending part of September 1982 trying to assuage another group that was unhappy with the move to change the school’s image. White alumni were bombarding the university with angry calls and letters after hearing rumors that UM had ordered a large supply of Mississippi state flags and intended to use them to replace the Confederate flags at sports events.

The university had only ordered one state flag, though, Meek told the Associated Press at the time, and had no intention of banning rebel flags on game day. In the years that followed, though, the school would do just that, and many UM graduates would stop attending football games in protest.

It is one of many changes in recent years that have angered some UM alumni. On July 14, 2020, the university moved the towering Confederate monument that has stood at the center of its campus for decades, and placed it instead in a Confederate cemetery on campus. Even that became controversial, though, with some critics accusing a little-known committee of mostly alumni of planning to reimagine the cemetery as a “Confederate shrine” on campus, with the monument as its centerpiece.

The Mississippi Free Press stirred the debate further with its interview with high-profile alumnus and UM donor James Barksdale and then its report in July that the school’s current master plan includes a “New Grove” and other developments adjacent to the statue’s new home should enrollment go back up enough.

Other vestiges of the school’s Confederate heritage remain unchanged. Though the university announced plans to rename it several years ago, Vardaman Hall retains the name of James K. Vardaman, a former Mississippi governor who was known for supporting the lynching of African Americans in the state and for backing laws that disenfranchised Black voters.

Lamar Hall, which houses the Office of Diversity and Community Engagement, is named for Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, a Mississippi plantation owner, an avowed white supremacist and one of the drafters of Mississippi’s Ordinance of Secession. During the Civil War, he served as a Confederate official and, afterward, held several positions in the U.S. government, including as a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

And like Mississippi State University, UM also has a building named for James Z. George, the U.S. senator who came home from Washington, D.C., in 1890 to write the anti-suffrage clauses of the new Mississippi Constitution that rolled back Reconstruction-era voting rights for Black Mississippians. George’s “suffrage” provisions included poll taxes, literacy tests, residence requirements and other provisions that were in place until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s brought federal reversal of the laws.

UM also has a stained-glass window in Ventress Hall that commemorates Confederate soldiers, and its athletes still play under the banner of “the Rebels,” a reference to the nickname for Confederate soldiers.

The changes UM has made, though, remain controversial among many white alums and even some current students, who accuse the university of attempting to erase history. Blake Tartt, the 1984 UM graduate, is among them.

‘The Money Will Dry Up’

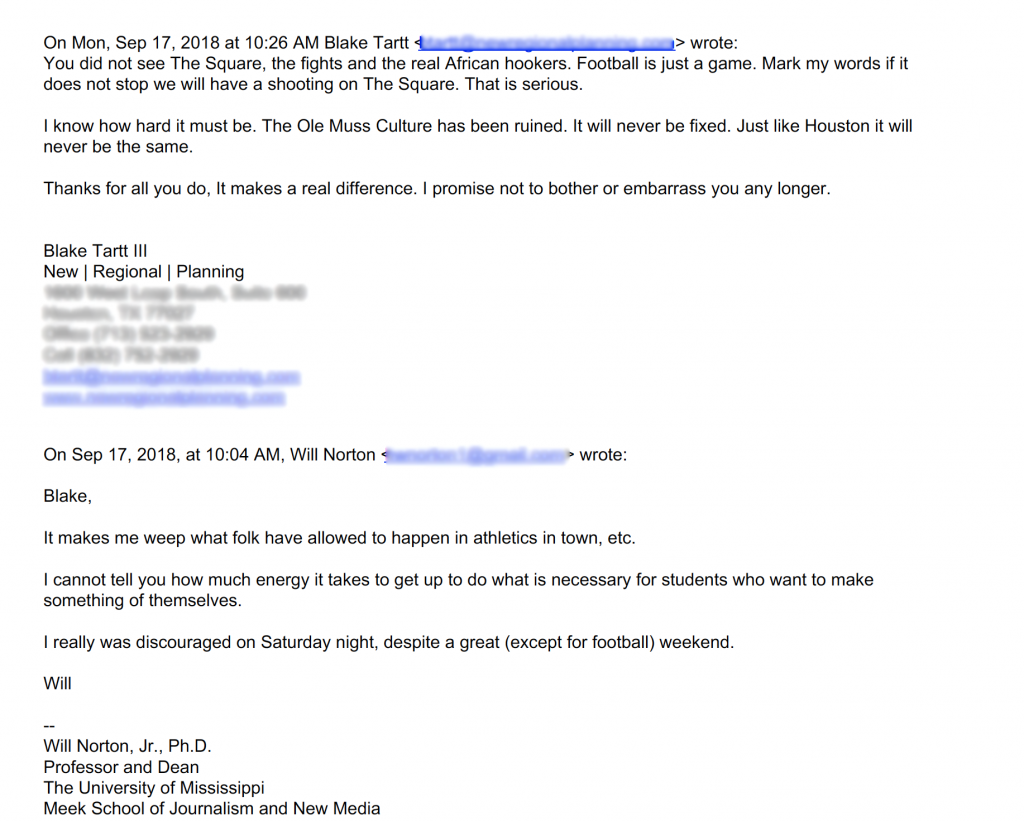

In the Sept. 17, 2018, emails with Will Norton, the journalism-school dean, Tartt lamented the fall of the Old South culture that had permeated the campus during his days as a party-loving fraternity student in the 1980s.

“You did not see The Square, the fights and the real African hookers. … Mark my words if it does not stop we will have a shooting on The Square,” the Houston businessman wrote to Norton, referring to the night in September 2018 when he watched in fury as Black students partied in downtown Oxford after UM’s football team lost to Alabama. “That is serious. I know how hard it must be. The Ole Muss Culture has been ruined (sic). It will never be fixed. Just like Houston it will never be the same.”

Norton wrote back, telling Tartt he was focused on “trying to keep building the Meek School” and that he could not “concentrate on the ineptitude around me.”

“I think the marketplace will bring about change in Oxford, but it will take a long time. These folk will have to hit rock bottom before something useful will hit,” Norton wrote.

Those remarks sent Tartt on a tangent about efforts to retire the school’s Old South image.

“Once a shooting happens they will all wish they never stopped playing Dixie and made up a stupid story about Colonel Reb,” Tartt wrote, continuing his Sept. 17 email correspondence with Norton. “Even the gangbangers and 62-7 beating by Alabama is bottom. The LANDSHARK is a disgrace to Ole Miss. … I had to watch the blind side to make me feel good about Ole Miss when I got home. I am really sick today because of all of this. I have work to do. I can take it any longer.” (sic)

“The Blind Side” is a popular 2010 movie starring Sandra Bullock that tells the story of Leighanne Touey, who helped Michael Oher, a disadvantaged Black teenager in Memphis, finish high school and go on to become a star UM football player before he joined the NFL. Critics often say the film, despite being based on a true story, is another in a long line of “white savior” films that make white people feel good without challenging them to look deeper for their own racist views and behaviors. The film often depicts Black characters negatively.

By February 2019, Tartt was still sending Norton emails in which he waxed nostalgic about UM’s bygone days of Dixie pride.

“Absolutely absurd and unfortunate how many lame out of state liberals, punk spoiled rotten millennials and racist faculty members have totally ruined what was the greatest place on EARTH! … The money will dry up,” the alumnus wrote on Feb. 13, 2019. “Those who tore the traditions apart will have no memories and realize how great the sound of DIXIE was when they can’t put food on the table.”

Tartt’s sunny recollections are at odds with the university’s reality in the early 1980s.

When it came out the spring after John Hawkins’ fateful decision not to carry the rebel flag onto the football field, the “Ole Miss 1983” yearbook featured prominently on its cover a black-and-white photo of the campus’ Confederate monument, dimly lit beneath a full moon with wispy, barren tree limbs hanging overhead.

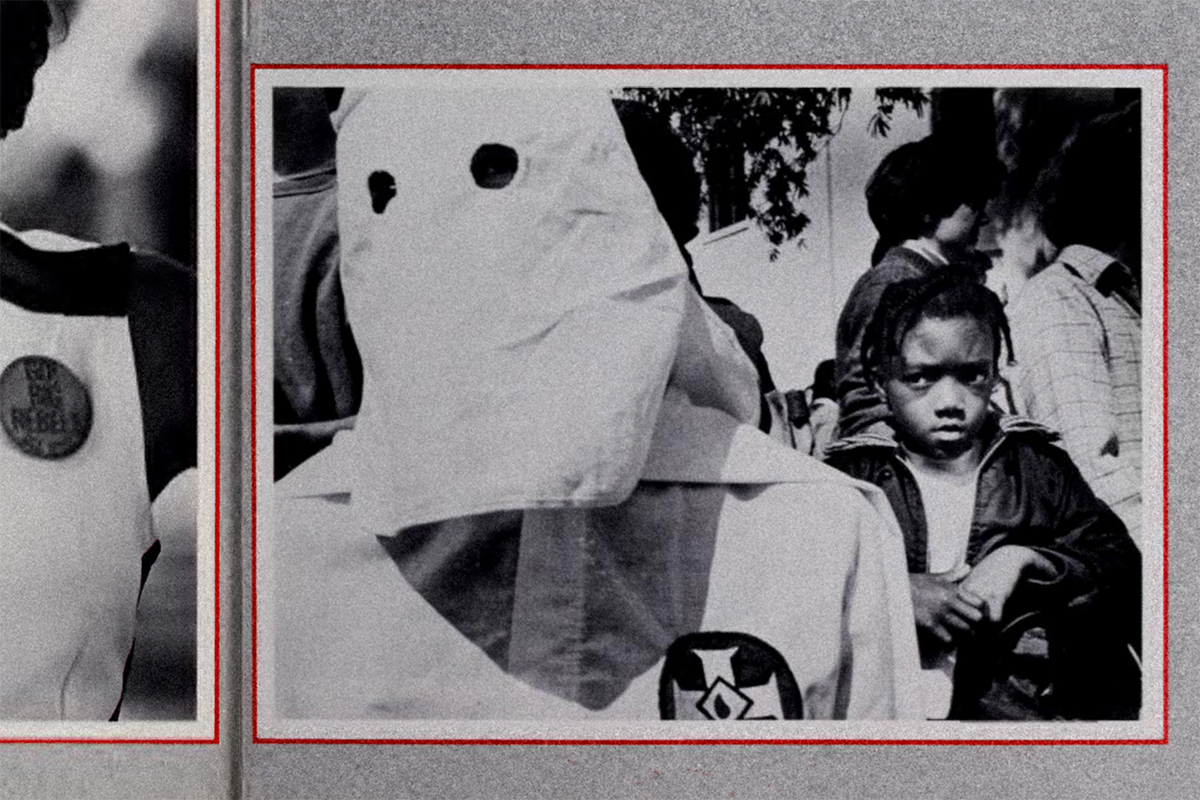

Inside, the yearbook showed just how all-consuming the fights over race and white southern identity became at the university during Tartt’s time as a student there. Page after page featured images of the Ku Klux Klan marching onto the campus, including one arresting photograph of a small Black girl peering over the shoulder of a hooded klansman.

In one February 2019 email, Norton sought to correct Tartt’s false recollection of a seemingly controversy-free UM in the early 1980s.

“Blake, you do not remember. In fact, until this year, I would say that the early 1980s were the most controversial I can remember at Ole Miss,” Norton wrote. “I had to go to the chancellor to ask the chancellor to ask one of our graduates, an African American woman, to return to Ole Miss to help Black students who were going to blow the place apart in controversy. … You, like so many kids today, truly enjoy the place and not knowing about the controversy.”

Students are not the ones who complain about changes at the university, the journalism dean added.

“The only people who talk bad about the place are alumni, … and it usually is those off the campus who are upset with the university,” wrote Norton (who, like Tartt, did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story).

Donors Revolted: ‘I’m Done With Ole Miss’

In fact, a number of donors and alumni, incensed by what they considered the university’s poor treatment of Ed Meek, threatened to shut off funds to the school in the fall of 2018.

Documents in the trove of emails show that a number of university officials, not just Norton, seemed to struggle to strike a balance between empathizing with aggrieved wealthy white donors who clung to the Ole Miss of yore and responding to a UM faculty and student body that, overall, felt the school was not moving fast enough into the future.

On Jan. 4, 2019, University Development Director of Communications Tina Hahn sent UM Vice Chancellor for Development Charlotte Parks a document containing remarks that former and potential future donors had made to UM employees over the course of the four months that had passed since Meek’s fateful Facebook post featuring black women on The Square in Oxford.

The informal report says that, on Sept. 21, 2018, The Neshoba Democrat’s editor and publisher, Jim Prince III, asked School of Accountancy Director of Development Jason McCormick to “have the alumni office discontinue my giving.”

“I’m done with Ole Miss. If you can give me a contact or have them call me to confirm, I would really appreciate it,” the document recounts Prince telling McCormick.

In addition to his leadership at the Neshoba Democrat, Prince is the president and CEO of Prince Media Group, which provides digital marketing services. He is also the publisher and the president of Madison County Publishing Co. Inc., which produces the Madison County Journal newspaper. In the past, he has served as the chairman and, separately, as the president of the Mississippi Press Association. He got his master’s in journalism at UM in 1991.

Meek is not a racist, Prince told McCormick, but “just the latest victim of the ideologically-driven, nameless, faceless mob whose offense trophy can never be filled with enough victims of deliberately twisted words and surmised intentions.”

“The debauchery on The Square is something that concerns all of us as graduates of the University. He was attempting to address a real problem, regardless of race. … Ed Meek is not the problem. Our culture has failed,” the document cites Prince as saying.

Sidna Brower Mitchell, a 1963 alumna and donor, said on Sept. 25, 2018, that the school should “not bother to ask (her) for any more donations,” Hahn’s document reports.

“Based on the way Ole Miss is headed, especially after the ‘outrage’ over Ed Meek’s Facebook post, I no longer feel loyal to nor do I care to donate to the University of Mississippi,” the document quotes her saying.

Mitchell was the editor of The Daily Mississippian, the UM newspaper, from 1962 to 1963—the tumultuous period when James Meredith enrolled as the university’s first Black student. After Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett, a segregationist Dixiecrat, stood in the doorway to block Meredith from registering in September 1962, a federal judge ordered that the state and the university must allow him to register.

When U.S. marshals attempted to escort Meredith onto campus, though, deadly riots, led by white supremacists and segregationists who feared his admittance would change the school’s culture for all time, broke out. President John F. Kennedy dispatched 3,000 federal soldiers to quell the violence before Meredith was able to attend classes.

Many white UM students voiced their opposition to Meredith’s admission at the time, including then 18-year-old freshman Don Barrett, who told New York Times Magazine in November 1963 that he felt, “as do most of the white population of the South, that the negro is inherently unequal.”

In a letter to the editor of The Daily Mississippian amid the Meek fallout in 2018, Sidna Mitchell cited her experiences as the paper’s editor during that tumultuous era to bolster her defense of Meek, whom she knew at the time.

In the document that Tina Hahn sent Charlotte Parks, Executive Director of Development Denson Hollis cited other donors who threatened to withhold funds over the university’s response to Meek’s post.

In a note on Oct. 2, 2018, Hollis recounted his meeting with Mike McDonald, the co-owner of Oklahoma City-based Triad Energy Inc. McDonald’s past giving included funding for a $100,000 accounting scholarship and $50,000 for UM’s law school.

“He is someone I had pegged for a naming in the new accountancy building,” Hollis wrote of McDonald. “He is very upset about the way the Ed Meek situation was handled and said he isn’t giving anything to Ole Miss for the foreseeable future.”

Hollis reported that Oxford resident Don Newcomb, the founder of the Newk’s Eatery and McAlister’s Deli food chains, was “very upset about the Chancellor’s handling of the Ed Meek situation.” Newcomb had already given $60,000, and Hollis had hoped to convince the donor to give another $40,000.

“I am paraphrasing this part, but he went on to say there are other places that deserve funding, that don’t act like this,” Hollis’ report reads.

University Ombudsman Paul Caffera sent emails to colleagues the next spring demonstrating the frequently stark contrast between the views UM officials collected from alumni and those they collected from current students and faculty. After a group of neo-Confederates rallied on campus in defense of the Confederate monument, Caffera described the comments he collected from around the campus as he sought feedback on the statue’s future.

“As of now, I have heard from 115 people. Every one of them wants the monument moved. Nobody has expressed support for keeping the monument in its current location,” Caffera wrote on March 7, 2019.

Among the dozens of donors and alums who told UM employees they no longer wanted to support the university financially during the fall of 2018, a number of them laid the blame squarely at Vitter’s feet.

“Chancellor Jeffrey Vitter threw a good man under the bus who has dedicated his entire life to make the University of Mississippi better and open to all. Vitter has divided the Ole Miss family and it is offensive,” the report quotes Jim Prince, the Neshoba Democrat publisher and editor, saying, which appears to come from a Facebook post he made on Sept. 21, 2018.

Steve Cockerham, alongside his wife, is listed on the UM Foundation website among donors who have given between $100,000 and $499,000. He opined that Vitter had made the Meek situation “exponentially worse by responding in public.”

“I have had my fill of him. No ambivalence anymore,” the document recounts him saying.

The development office’s document quotes Stephen Cawthon, an alumnus from Dallas, calling for Vitter’s removal.

“That giant sucking sound is hundreds of thousands of (dollars) being sucked from the Alumni Association, sponsorships, donations, enrollment, etc.,” the document quotes Cawthon saying. “No one wants to be a part of this Vitter inspired, race baiting, history revisionist ideal that is being promoted as the Ole Miss utopia. As part of the Dallas alumni I will do everything I can to facilitate the removal of Vitter and to stem the flow of (money) into the university.”

‘Open Racism and Rebel Flags’

Even as he came under fire from alumni who blamed him for Meek’s downfall, Vitter faced a new danger on the horizon, as four sociology professors prepared to publish the results of their “Race Diary Project.” The academics had collected 1,400 diary entries during the 2014-2015 school year from 621 students who described a number of racist, sexist, Islamophobic, homophobic and otherwise discriminatory incidents on campus.

In an Oct. 3, 2018, email to colleagues that The Daily Mississippian previously reported, UM Chief Marketing and Communications Officer Jim Zook wrote that “Chancellor Vitter (was) particularly concerned about the characterization of the university” in the report.

“We are very concerned about the potential impact of this report on the university and its reputation. Chancellor Vitter is particularly concerned about the characterization of the university,” Zook wrote.

The sociology professors published their report, titled “Microaggressions at the University of Mississippi,” on Oct. 10, 2018—about three weeks after Ed Meek’s calamitous Facebook post. Without naming the students who had written the diaries, the report described a number of shocking incidents. In one instance, a Black freshman woman said she was walking on campus when a white male student told her to “move, you Black n*gger.”

A white student shared a story of attending a party where drunk male students played a drinking game in which they took turns singing the words, “F*ck you n*ggers,” and had to follow up with a rhyming second line.

In another notable diary entry, a white fraternity student described a conversation about a Black rushee whom his fraternity brother described as “a cool guy that actually went out of his way to shake our hands and introduce himself with a smile.”

“And we can’t accept him to our chapter because mostly all of our Alumni will stop donating money, give us the finger, and never come back for admitting one black guy in the fraternity,” the diary entry, which does not name the allegedly discriminatory fraternity, recounts the fraternity brother saying.

Brian Powers, a white UM alum, told the Mississippi Free Press that those descriptions did not surprise him. He attended UM as an undergraduate student twice, first as an 18-year-old for one year in 1995, and then again when he returned to finish his bachelor’s degree at age 36 in 2013.

In fall 1995, Powers pledged with Phi Gamma Delta. That fraternity had formed three years earlier as only the second fraternity at UM with a racially diverse founding pledge class. The class in 1992 included one Black student and two Hispanic students, while the rest were white. There was at least one Black student in the organization when he pledged, Powers said. Despite that, members of his fraternity wore custom-branded shirts that included the Confederate flag, like other white UM fraternities did.

“There was open racism and rebel flags everywhere on campus—hanging in dorm rooms, hanging everywhere. I remember shirts that would have Nathan Bedford Forrest on the back of them at some fraternities’ parties,” Powers said, referring to an infamous former Confederate general who helped found the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War. “Just openly racist and Confederate stuff.”

Powers said he saw members of other fraternities direct explicitly racist behavior toward Phi Beta Sigma, a Black fraternity on Fraternity Row.

“They were in a little house in the middle, and people threw shit at their house and yelled the n-word at them all the time. I can’t tell you how many times I heard that in 1995,” Powers said.

He left UM in 1996, at a time when then-Chancellor Robert Khayat was beginning to implement a series of changes that would remake the face of the university—at least cosmetically.

When Powers returned as a journalism student in 2013, the atmosphere among students was markedly different, he said. Confederate flags were no longer ubiquitous, but he did see some white students defiantly carrying Mississippi State Flags after a push to change the state symbol began in earnest in 2015. Oxford had also changed since his early adult years, Powers said, noting that the crowds of students that would congregate in The Square in the mid-2010s were significantly more diverse than the almost exclusively white crowds he remembered seeing in the mid-’90s.

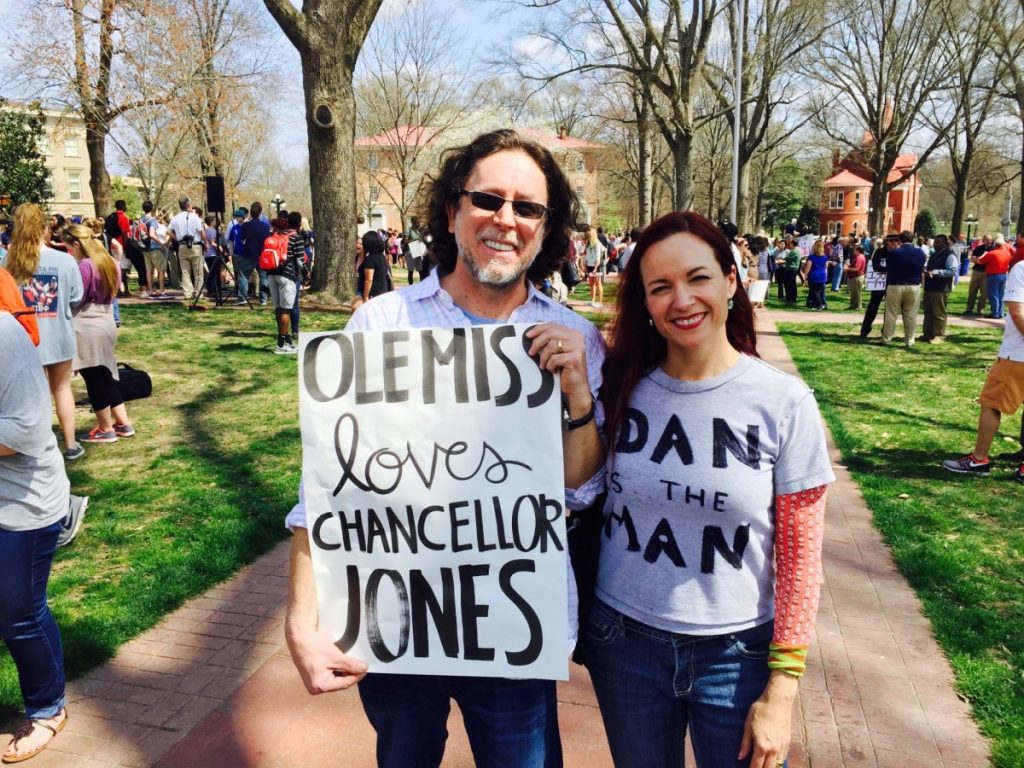

Still, not everything had changed, Powers said. Fraternities and sororities on campus remained largely segregated, for instance. He felt confident, though, in the leadership of then-Chancellor Dan Jones, who had held the position since 2009 and, like Khayat, implemented some modest reforms aimed at updating the university’s image.

“As far as I’m concerned, Bobby Khayat and Dan Jones are the two best chancellors they’ve ever had at the University of Mississippi,” Powers told the Mississippi Free Press.

The Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning, though, felt differently. In March 2015, Jones announced in an open letter that IHL had told him “that they will not renew my contract as Chancellor of the University of Mississippi.” Board representatives told him that the decision was related to his “unwillingness to adjust to the board’s desired governance structure” and issues relating to the university’s medical center.

The dismissal sparked protests on campus, but IHL did not relent. Khayat criticized the firing in a Clarion-Ledger op-ed, calling Jones’ ousting an “evil deed” that was “clearly motivated by personal and/or political reasons and not on performance.”

In October 2015, then-IHL Commissioner Glenn Boyce announced that the board had chosen New Orleans native Jeffrey Vitter as UM’s new leader.

Three years later, though, IHL would sour on him, too.

Downfall of a Chancellor

On Oct. 10, 2018, the same day the race diaries report went public, a displeased Vitter submitted and The Daily Mississippian published an op-ed, which emails show he wrote with assistance from Zook and others at the university. In it, the chancellor said he disagreed with “the assertion in the report that the University of Mississippi ‘has made halting but tangible progress toward creating an inclusive campus environment’” since 1962. Instead, he said, the school had made “sustained, substantial, and measurable progress.”

Vitter pointed to the fact that one in eight, or nearly 13%, of UM undergraduate students are African American. Comparatively, the student body at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg is 28% Black—a much closer representation of Mississippi’s overall population, which is 38% Black. The student body of Mississippi State University in Starkville is about 19% Black. Delta State University, a smaller publicly funded university in Cleveland, Miss., is about 61% white and 31% black.

In his letter, the chancellor also criticized the report for its “anonymized” approach to the diaries project, ensuring university officials “have no way to reach out to those affected by these incidents.”

Sociology professor James Thomas, one of the report’s authors, was “livid” with Vitter’s op-ed, he told The Daily Mississippian in February 2019. He also implied that he thought the chancellor may have written the op-ed as an attempt to dampen the rage of wealthy alumni.

“A chancellor’s first responsibility is to the institution and his faculty and his students. It’s not to your donors or any people outside of the university who claim they have a stake in it,” The Daily Mississippian reported Thomas saying. “It’s to the people on this campus. Period.”

But if the embattled chancellor thought that criticizing the explosive report would help save his job, he was mistaken. The authors of the report were inundated with hate mail, including some threatening messages, and other critics began combing through their social-media timelines.

The Mississippi State Flag Foundation, a group that opposed changing the 1894 flag that nevertheless came down last month, drew widespread attention to a tweet Thomas sent on Oct. 6, 2018. That was the day the U.S. Senate narrowly confirmed Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court even as questions swirled about sexual-assault allegations.

“Don’t just interrupt a senator’s meal, y’all. Put your whole damn fingers in their salads,” Thomas tweeted that day. “Take their apps and distribute them to the other diners. Bring boxes and take their food home with you on the way out. They don’t deserve your civility.”

The flag group’s post about the sociology professor’s then-week-old tweet spread quickly, and conservative national outlets like Fox News and Breitbart lapped it up, stoking nationwide outrage. In an attempt to distance himself from yet another story sure to infuriate donors, Vitter made another public statement on Oct. 14, saying he “condemn(ed) statements that encourage acts of aggression.”

For over a year, the sociology professors had been in talks with Provost Noel Wilkin about hosting a forum after the report’s release to discuss “effective strategies” for making change, but the forum, which had been planned for November, was one of the first casualties of the firestorm that followed the report’s publication.

In the days after Thomas’ post went viral, officials reported another round of comments from alumni, the January 2019 dossier of donors’ complaints shows.

“I received an angry phone call from Nate Howell. He said he will not be giving any more money to the university until (the) administration does something about Sociology Professor James Thomas,” University of Mississippi Foundation Stewardship and Records Assistant Abigail Robbins reported on Oct. 18, 2018. “I tried to transfer him to anyone else, but he only wanted to yell at me.”

Hollis, the UM Development Department director, reported four days later that “Dr. Chan Henry … told me he wants to stop funding the Rexine Henry Scholarship endowment based on recent events at the university, specifically the handling of the Ed Meek situation and also the social media post from OM faculty member, JT Thomas.”

Dr. D. Chan Henry, a Jackson resident, established the Rexine M. Henry Memorial Scholarship Endowment in 2016, naming it for his wife who had died of breast cancer six years earlier. In a statement at the time of its launch, Dr. Henry called the endowment “a permanent memorial to my wife and mother of my children.”

Then, UM Foundation Annual Gifts Officer Alyssa Vinluan reported on Oct. 27 that Jeff Cosman said he was “not interested in supporting Ole Miss if this man is employed by the university,” calling Thomas “disgusting” and saying the university was not “doing enough to drain the swamp of alumni and professors who want the old ways or divisive new ways—in both athletics and academics.”

On Oct. 29, Vinluan also reported that Paul Howell, a lawyer in Gulfport, told her that he was “very frustrated” about events at the university, “mainly the Ed Meek controversy and the sociology professor.”

“He felt that if Ed’s name was going to be removed from the journalism school, then the sociology professor should be fired no questions asked,” Vinluan reported. (Instead, Thomas narrowly became a tenured professor soon afterward, despite an effort to stop his promotion).

The complaints continued to come in, and 11 days later, on Nov. 9, 2018, the university announced that Vitter’s reign as the school’s 17th chancellor was coming to an end.

Brian Powers, who had investigated IHL’s firing of Dan Jones when he was a journalism student in 2015, pointed out that the IHL board consisted entirely of members appointed by former conservative Gov. Phil Bryant at the time of Vitter’s late 2018 ousting. Bryant graduated high school from a Citizens Council segregation academy and, as governor, quietly continued the annual tradition of declaring April as “Confederate Heritage Month” in Mississippi.

Powers said he thinks that many of the IHL members likely had the same central issue with Vitter that they had with the New Orleans native’s predecessor, Jones.

“They wanted a yes man,” Powers said. “They thought Vitter would be the yes man, but he wasn’t.”

Dean Norton Called Leak ‘Treacherous’

In October 2018, while Vitter was trying to save his job amid mounting controversies, then-Mississippi Today reporter (now editor-in-chief) Adam Ganucheau first reported some of the aforementioned remarks from the Sept. 20 Meek School of Journalism and New Media faculty meeting, which occurred the day after Ed Meek’s infamous Facebook post. Ganucheau had obtained a copy of the recording of the meeting from an anonymous source.

Though Ganucheau’s story quoted some of the same remarks from Usery and West as the Mississippi Free Press reported in Part I of this package, it omitted the fact that both women said Meek obtained the photos and the idea for a story about “prostitutes” from Blake Tartt, whom Ganucheau did not mention in the story.

“Meek, who was traveling the weekend of the Ole Miss-Alabama game, did not take the photos of the women, but received them from an acquaintance in Oxford,” the Mississippi Today story reads. “The story idea Meek passed along was that prostitution and fights were hurting Oxford’s character and long-term financial viability, implying that the women in the photos were sex workers.”

Mississippi Today is a nonprofit online news publication. Its board of directors includes nine members, including seven who are either UM alums, administrators, faculty members or donors. Will Norton was on the board until he suddenly stepped down in mid-July of this year.

Norton’s emails show that, on Oct. 11, 2018, Ganucheau reached out to him, saying he was finishing up a story on “the Ed Meek situation” that he expected Mississippi Today would publish the next week. The reporter asked Norton if he would mind speaking by phone or meeting in person to discuss the story.

“I know you’ve been forced into a tough position with all of this, and I hope you know I’ll be fair to you, the school, and everyone involved,” Ganucheau assured the dean and Mississippi Today board member, who later agreed to talk. Ganucheau is a 2014 graduate of the UM journalism school.

On Saturday, the Mississippi Today reporter-turned-editor told the Mississippi Free Press that he repeatedly sought to confirm that Tartt was the source of the photos in 2018, but was unable to do so. Mississippi Today’s journalism operates “completely independently of our board of directors,” he said in a statement.

“Any suggestions that I didn’t do my due diligence as a reporter to tell any complete story is offensive to both me and my colleagues. It’s just plain wrong,” Ganucheau said in the Aug. 1, 2020, statement. “Before that October 2018 story published, the only information I had that suggested Blake Tartt took the photos in question was complete hearsay. So I did what every good reporter does: I diligently dug to prove it. I called Tartt’s cell phone and Houston office several times and left messages with his assistant.”

The Mississippi Free Press also tried repeatedly to reach out to Tartt for this story and left several messages, but never heard back. In his Aug. 1 statement, Ganucheau said he even reached out to some of Tartt’s acquaintances to find out if any of them could confirm that he was the source of the photos. He did not say whether Norton was one of those acquaintances.

“No one I talked with in the course of my reporting confirmed it. As has always been our practice, we don’t publish unsubstantiated rumors. Plus, the main purpose of that story was to inform readers about the influence of Ed Meek at the university through the lens of current students and alumni who were understandably devastated by his actions,” Ganucheau said. “While I would’ve loved to have included who took those photos and was disappointed that I couldn’t, we published what we could confirm. That’s what we do.”

The reporter’s story went live on Oct. 18, 2018—a day shy of a month since Meek’s post had rocked the journalism school.

The article set off what several sources characterized as a “witch hunt” in the UM journalism department to find the person who had taped and leaked the recording of the Sept. 20 faculty meeting. Norton’s emails show that faculty members were incensed about the leak, particularly Anna Grace Usery.

The day after Mississippi Today published Ganucheau’s story, Usery wrote to Norton to say that her trust in her colleagues had “been broken.”

“I don’t ask that consequences are sought. However, I do know I can trust you to emphasize (that) if we’re teaching ethical journalism then it might be in good taste to practice it,” Usery wrote, noting that Norton had suggested on some prior date that the meetings should be considered “off the record.”

Norton passed the message along to Provost Noel Wilkin and UM Chief Legal Officer and General Counsel Erica McKinley, assuring Usery that university officials would have a meeting to deal with the internal whistleblower issue.

“Many faculty are upset about this breach of confidentiality and what I would call treacherous behavior that has the potential to breed distrust among our faculty and staff,” Norton wrote to Wilkin and McKinley about the leaked recording.

Meek confirmed to the Mississippi Free Press in late July that Blake Tartt sent him photos of women on The Square after the UM game against Alabama in September 2018, but said other people sent him photos that night, too. He said he was not sure who made the photos he used in his post.

Tartt Pushed for ‘Changing of the Lyceum’

Weeks after Ganucheau’s story published, on Dec. 1, 2018, Tartt emailed Norton with a suggestion: “Please go be Chancellor!”

“Blake, I would never be named,” Norton replied. “Through the years, I have refused to go above dean. Being dean is the best job on the campus. … Being chancellor is plastic. It is not a position that educates.”

Months before Vitter’s sudden removal, though, in August 2018, Tartt was already speculating to Norton about who the next chancellor would be, despite the fact that Vitter had not announced plans to retire. It is not clear why the men seemed to assume that the chancellorship would soon become available.

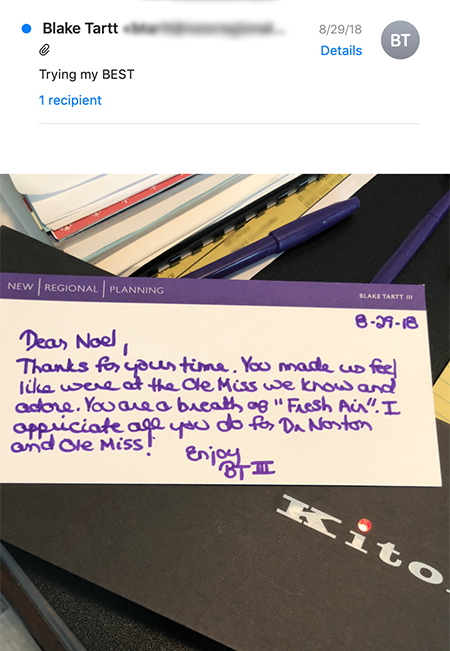

On Aug. 29, 2018, Tartt sent the journalism dean a photo of a handwritten note addressed to Vice Provost Noel Wilkin atop a black box with the word “Kiton” on it. Kiton is a men’s luxury brand that sells ties. Prices for Kiton ties are listed online and typically range from $150 to $300.

“Dear Noel, thanks for your time. You made us feel like were (sic) at the Ole Miss we know and adore,” Tartt wrote in a bubbly writing style that mixed cursive and print. “You are a breath of ‘fresh air.’ I appreciate all you do for Dr. Norton and Ole Miss! Enjoy, BT III.”

Referring to Wilkin in a separate email that day, Tartt wrote to Norton: “We want to take extra good care of him and nothing but positive comments. Who knows maybe they make him Chancellor. He would be excellent.”

“Blake, Wicker will be a help. So will Dr. Dye,” the Meek School dean wrote back, perhaps referring to Republican U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker, a UM alum with whom Tartt had reached out to that morning to arrange a future lunch meeting, and Ford Dye, a member of the IHL Board of Trustees. That same body would, nearly a year later, appoint Tartt to the chancellor search committee.

In the Aug. 29, 2018, email, Tartt noted that Wicker was once president of the Ole Miss Associated Student Body and that overhauling leadership in the Lyceum, the iconic building on campus that represents the school administration, would require “building…relationships.”

“We need to get all of the people close to us. Changing of the LYCEUM is going to happen,” Tartt wrote. “No way they (sic) the current group survives!”

‘This Corrupt Search’

Three weeks before the IHL Board of Trustees announced that Tartt would serve alongside Wilkin and 37 others, the board appointed Dr. Ford Dye, whom Norton had referenced in the August 2018 emails, as the chairman of the board search committee. The appointees spent months considering possible candidates before delivering its list of recommendations to IHL.

But the man that IHL ultimately chose for UM’s new chancellor was not even been among the finalists that the committee had recommended. Instead, IHL selected its own former commissioner, Glenn Boyce, as the school’s new leader on Oct. 4, 2019. Boyce, who had stepped down from his role as commissioner earlier that year, served as a consultant for the IHL board during the search process.

Boyce’s past as a coach at three historic segregation academies drew criticism, but some search committee members suspected that IHL had already decided on Boyce before they ever made their recommendations.

The documents the Mississippi Free Press examined show that Aimee Nezhukumatathil, an English professor and member of the committee who is of South Indian descent, wrote in an email to the IHL board that she had “never been placed in a more corrupt situation than the one I experienced as part of this committee.”

“I want you all to know what it means for me to have put time into this corrupt search,” wrote Nezhukumatathil, a poet who teaches creative writing.

In the email, Nezhukumatathil noted that she had just finished a book tour when she learned of her appointment to the committee from a friend who had seen a newspaper announcement. That summer, she cut a family road trip short so she could attend the chancellor search committee’s first meeting.

“As a mother, as a scholar whose publication record is active and thriving, and as a person of color, the stakes are much higher for me than others: just this past week, I received an anonymous message online where I was told if ‘[I] don’t like the outcome of the search, [I] can just go cry in my curry,” she wrote. (Curry refers to a variety of popular Indian dishes whose ingredients include spices like turmeric, cumin, ginger and dried chillies.)

To make matters worse, some alumni seemed to learn about the decision the night before IHL informed the members of the search committee. At 6:59 p.m. on Oct. 3, Ed Meek posted on Facebook announcing that Boyce would be the next chancellor; search committee members learned the next morning in an email.

‘Ed Has Lost His Mind’

Ed Meek’s ties to the university run deep. As UM’s spokesman in the 1980s, he staunchly defended the university across a series of controversies, including in the latter part of the decade.

In August 1988, Phi Beta Sigma, the predominantly Black fraternity that had been accosted five years earlier by a white mob that Meek likened to “a spring pep rally,” was preparing to move into a house on the all-white Fraternity Row. Events pushed the integration back several months, though, after the house caught fire, triggering an arson investigation.

The next fall, in September 1989, several pledges with Beta Theta Pi, a white fraternity, allegedly kidnapped an active member of the fraternity, along with another pledge, in retaliation for a hazing ritual. They stripped the two naked and painted their pale bodies with racist graffiti.

The pledges drove the two victims of the prank about 35 minutes and dropped the young students off on the campus of Rust College, a historically Black institution in Holly Springs, Miss. There, around 50 Black college students stared at the two stranded white men, whose nude bodies bore words and phrases like, “We Hate N*ggers” and “KKK.” Two Rust security guards took them into custody as they tried to sneak off the campus and draped them in towels before returning them to Oxford, historian David Sansing wrote in his book.

With UM’s embattled Greek system already staring down accusations of racism from the previous year, Ed Meek did his best to minimize the situation.

“They had no idea there were racial connotations in it,” Meek told the Associated Press in September 1989, referring to the pledges who painted the n-word on the victim’s bodies. “They should have, but they appeared not to have viewed it that way.”

Nevertheless, Meek told the AP at the time, UM was treating it as “a very serious violation of good taste and ethics on our campus.” The chancellor at the time, R. Gerald Turner, banned Beta Theta Pi from the university for three years.

While Meek retained important relationships with people in or connected to the university after the 2018 controversy and remained in-the-know about the IHL’s machinations, tensions remained between him and leaders in the journalism department.

In November 2019, UM journalism faculty members fretted over a Meek Facebook post once again, when the ex-donor shared a letter that Lee Habeeb, an Oxford columnist and talk radio host, had written to Vice Provost Wilkin. He criticized the Overby Center’s decision to refuse to allow Elisha Krauss, a right-wing speaker and Daily Wire contributor, to speak.

The Overby Center responded that it only allowed partisan voices on panels that included competing viewpoints. UM officials quickly reinvited Krauss to speak on campus in a different venue.

Leslie Westbrook, a wealthy adjunct assistant professor of marketing, wrote to Norton, expressing concern about Meek’s continued public criticisms.

“Ed has lost his mind. May the Force be with us!” she wrote.

For a while, emails show, Westbrook had been nervous that a spate of controversies could undermine the effectiveness of financial contributions she had pledged to the school of journalism. The IHL’s dramatic appointment of its own former commissioner as chancellor a month earlier had already unnerved her, and now Meek’s latest remarks served as another piece of evidence that the fallout from the September 2018 controversy was still churning.

The UM investment committee reported in early November 2019 that it had missed its fiscal-year 2019 goal of $118.6 million in contributions, closing the year short by $15.8 million instead. An email from UM Vice Chancellor for Development Charlotte Parks that month cited a “turbulent year,” and specifically pointed to controversies involving Ed Meek, J.T. Thomas, Confederate monuments, the new chancellor and UM basketball players kneeling during the national anthem.

In another email on Nov. 12, 2019, to UM Foundation Director of Stewardship Donna Patton, Parks highlighted a pair of wealthy donors who had concerns stemming from the Meek situation. Billionaire brothers Jim and Thomas Duff, the two wealthiest people in Mississippi, had agreed to give $26 million to the university over a 20-year period to fund a new 202,000-square-foot STEM building with their names on it. It would be the largest construction project in campus history, but the Duffs had a stipulation, the development vice chancellor wrote.

“Also, Jim wants some kind of statement in the agreement that would address this situation: If the university takes their names off the building, they want their money back. (This is because of the Ed Meek situation. They said they are conservative, non-drinkers, but someone associated with them could do something bad and then the university might associate that bad behavior with the Duffs),” Parks wrote.

The Duff brothers, who live in south Mississippi, founded and own Duff Capital Investments, a holding company that turns over billions annually; they also own Southern Tire Mart, which they inherited from their father, Ernest Duff. Thomas Duff is a member of the IHL board.

UM announced the Duffs’ $26-million gift on Feb. 5, 2020, saying in a press release that it will help fund the Jim and Thomas Duff Center for Science and Technology Innovation, which “is projected to be one of the nation’s leading student-centered learning environments for STEM education.” The building will cost about $160 million altogether, the university said.

‘They Are Our Enemies’

In late November 2019, emails show that Leslie Westbrook’s frustrations reached a boiling point. An expert in crisis management, she helped engineer Tylenol’s comeback after disaster struck in 1982, when seven people in the Chicago area died from poisoning after taking Tylenol capsules that an unknown killer had laced with potassium cyanide.

Her experience in crisis management, she indicated in the email, would have been helpful in resolving tensions with the Meeks.

“The Meek issue is far from over. Will, when you hosted the J School Board meeting not long after the Meek debacle, I strongly lobbied for a reconciliation; I was willing to devote whatever it took to create an approach to reconcile with Ed and Becky that could be acceptable to the key players,” Westbrook wrote in a Nov. 25, 2019, email to Norton and Parks, referring to Ed Meek and his wife. “I was ‘voted down’ (unofficially). I have a whole lot of experience with crisis management and believed wholeheartedly that I could have found a solution. Now it is far too late.”

Charles Overby, who is the Overby Center’s namesake and has been a member of the board of directors for news site Mississippi Today alongside Norton since its inception in 2016, had tried to assuage her concerns, she wrote.

“My longest time dear friend Charles Overby told me that, in his opinion, (it) was not a crisis and would eventually die down,” she wrote. “It has not died down. Ed took his money back. Every time there is an opportunity for Ed to reiterate that you, Will and the faculty threw him under the bus…he has jumped on it with fervor. It is not over. We did not need Ed and Becky as enemies. They are our enemies.”

Westbrook noted that she had already donated $400,000 of a pledged $500,000 to the UM Foundation for a planned consumer research center. Now, though, she had begun to doubt the project would ever reach fruition. She told Norton she wanted information on the project’s progress.

“I ONLY want reality, facts, not blue-sky hopes and dreams,” she wrote. “Yes, please confirm that you got this email. However, please do not attempt to address my concerns and discouragement in the short-term. That will lack credibility.”

Westbrook then mentioned a pledge of $2 million in estate assets that she had been in talks with the school about making to the journalism school upon her death.

“If I do not feel completely confident sometime within the next six months that the new addition will be built in a realistic and defined timeframe, I will change my will as well as look to not donate the final fifth of my original pledge. As you can tell, I am very discouraged and lacking hope. There was no good time to send this message,” Westbrook wrote.

Norton apologized, saying he had attempted to reach out to Meek to smooth things over, but “no reconciliation (had) been possible” because the former donor had refused to speak with him.

“He believes I orchestrated this against him,” Norton told Westbrook.

Despite tensions with Norton and others in the journalism school, the emails show that, throughout 2019, Meek worked to connect Charlotte Parks and other officials with wealthy potential donors (though he did complain in at least one email that year about the university’s continued sidelining of him).

The trove of emails also shows that UM officials continued to court Blake Tartt throughout 2019, with Charlotte Parks inviting him to lunch several times.

By late 2019, though, Norton seemed to have given up. Tartt sent the dean an email on Nov. 20 complaining about the fall in home-game attendance since 2016 and a 13% drop in student enrollment.

“Something really wrong with ALL managers at Ole Miss and all of the changes made by that past management group in the Lyceum and different schools within the university have FAILED,” Tartt wrote. “Now that we have a new leader hopefully necessary changes will be made.”

“Blake, thank you for your insights,” Norton replied curtly.

The journalism dean forwarded the email to Provost Wilkin and Vice Chancellor for Collegiate Athletics Keith Carter.

“Noel and Keith, I thought you should see this email from Blake Tartt and my response to him. He has not contributed to our school despite our attempts to be kind to him. He is in agreement with Lee Habeeb and Ed Meek,” Norton wrote.

A source familiar with conversations among journalism faculty said Tartt never gave any money to the School of Journalism and New Media, and that the Tartt-proposed retail communications program that the department hired Chip Wade to start up never got funded. Documents show Wade never taught another real-estate communications class after the fall of 2018.

‘Are We in Nazi Germany?’

Even as Norton and others in the school worked to win back funding for the university that the fall 2018 controversies had threatened, he and the rest of the journalism faculty were pushing back against another threat from within: a potentially oppressive campus media policy.

Patricia Thompson, the faculty adviser for The Daily Mississippian, the campus newspaper, emailed the journalism dean and several other faculty members on Sept. 10, 2019, complaining that the Associated Student Body had tried to bar a photojournalist for the campus publication from taking pictures during a public meeting that evening.

“Will, do you know what is going on? What is motivating this? … Unsettling to say the least,” Leslie Westbrook wrote the next day.

“It is from Jim Zook,” Norton replied, referring to the UM chief marketing and communications officer.

“WHAT DOES ZOOK HAVE AGAINST DM?” Westbrook replied.

“It is the whole administration,” Norton wrote.

“Against DM? DM???????? why?????? I am flummoxed!” Westbrook replied.

“Stupid policy. It will hurt the university dramatically,” Norton said.

Westbrook, still confused, responded in all caps, asking Norton if he knew the rationale for the restrictive policy.

“They do not want bad news getting out. They have made a lot of mistakes in administration, and they think that the controversy will stop if they shut down the student newspaper,” Norton wrote.

“OMG!!! Are we in Nazi Germany?” Westbrook replied.

Questions about the policy and its implications for student journalists continued to swirl throughout late 2019 and into early 2020, but The Daily Mississippian was not shut down.

On March 1, 2020, The Daily Mississippian reported on a draft policy proposal that, if approved, would “allow faculty members to speak with members of the media without university approval about only research, scholarship, professional expertise or as private persons,” but require them “to seek advance approval” from the University Marketing and Communications department before speaking to journalists in other instances.

The policy would encourage faculty “to notify deans, department chairs/heads and UM&C when discussions with a member of the media have occurred.” Under the proposal, journalists would need to notify a UM&C staff member when arriving on campus, and a designee would then escort them to their destination on the public university campus. The proposal says faculty “should” notify the department if they learn that a member of the media plans to come to the campus.

Critics of the proposal say it would further “chill” free speech at the public university. Several of the anonymous sources who spoke to the Mississippi Free Press for this story say it is just another layer of control that some UM officials hope will help the institution avoid future Meek-like public controversies—especially ones that could upset the delicate sensibilities of wealthy alumni and the flow of funding to the university.

In one Feb. 26, 2020, email, Charlie Mitchell, a journalism-school associate professor, criticized the proposal.

“The last thing a PUBLIC university worried about its image should do is shield faculty from public inquiries. No one is ever required to answer any media inquiry, but it’s a disservice to faculty advancement—as well as an insult—to posit that because someone may say something untoward or outside their lane that all communications should or must be screened,” he wrote.

The resolution to the battle over the media policy proposal, though, would have to wait, as school administrators and faculty shifted gears toward focusing on a more immediate threat: the COVID-19 pandemic.

Continue reading “The UM Emails: Part III” here.

Editor’s Note: In the reporting of the UM emails series and follow-up reports, the MFP did not confer with members of either of our boards or any donors associated with the University of Mississippi to avoid conflicts of interest.

Also see: From Racist Emails to ‘Witch Hunts’: A UM Emails Timeline

Watch: Reporter Ashton Pittman and Editor Donna Ladd discuss the series during the 2021 Ancil Payne Award for Ethics in Journalism ceremony (40:00) and read more about the award here.

Read the full UM Emails reporting series to date:

- ‘The Fabric Is Torn In Oxford’: UM Officials Decried Racism Publicly, Coddled It Privately

- ‘The Ole Miss We Know’: Wealthy Alums Fight To Keep UM’s Past Alive

- UM’s ‘Culture Of Secrecy’: Dean Quit As Emails Disparaging To Gay Alum, Black Students Emerged

- ‘Appalling’: UM Provost Decries ‘Hurtful’ Emails About Black Women, Gay Alum

- Ole Miss’ Coddle Culture: Ole Miss Will Stay ‘Ole Miss’ Without Radical Shift

- EDITOR’S NOTE: The Decisions, Process, Motives Behind Ashton Pittman’s Series On UM Emails

- Perpetuating Patterns: It’s Time To Build A Better University Of Mississippi

- After UM Emails, Dean Plans ‘Anti-Racist’ Training, Donor Changes to ‘Remake Our School’

- ‘Ole Miss’ Vs. ‘New Miss’: Black Students, Faculty On How To Reject Racism, Step Forward Together

- UM Closely Guards Climate Survey Providing Window Into Social Issues, Sexual Violence

- UM Probes Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails As Ex-Dean Keeps $18,000 Monthly Salary

- ‘Our Last Refuge’: UM Faculty ‘Terrified’ As Officials Target Ombuds In Bid To Unmask Whistleblowers

- ‘Like He Was Disappeared’: UM Faculty Fear Retaliation After Ombudsman Put On Leave

- UM Appoints Acting Ombuds As Weary Faculty See Effort To ‘Stamp Out’ Anti-Racism Voices

- UM Retaliating Against Ombudsman for Protecting Visitors’ Privacy, Org Says

- UM Accuses Ombudsman of ‘Raising False Alarms’ Over Whistleblower Investigation

- A Matter Of Trust: UM Controversy Shows How Ombuds Programs Should, Shouldn’t Function, Expert Argues

- UM Pursuing ‘Criminal Investigation’ Into Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails

- Ombuds ‘Exonerated’ As UM Emails Whistleblower Hunt Fails to Identify Sources

- Will Norton, Ex-Dean in ‘UM Emails’ Race Saga, Quietly Departs University