By the time Florida had dunked the nation’s first presidential election of the new millenium into a roiling sea of mayhem, Mississippi had already moved beyond Bush v. Gore and onto another battle more than a century in the making. Angry tirades and racial epithets dogged the members of Gov. Ronnie Musgrove’s flag commission in the fall of 2000 as they traveled across the Magnolia State, allowing residents to weigh in on whether Mississippi should keep its 1894 state flag, which includes the emblem of the Confederacy, or retire it in favor of a more unifying design.

Musgrove’s commission included a number of black and white state officials.

At one stop in Moorhead that month, a white Jackson resident, Jim Giles, used his speaking time to take special aim at Mississippi House Rep. Ed Blackmon, a black lawmaker from Canton. At the time, Giles led an organization called the Southern Initiative, which he had founded in 1994 “to promote pride in Southern heritage.”

“Mr. Blackmon, sitting over there in a thousand-dollar suit, I live in a trailer in the woods. You may have more money than I’ve got, you may have more power than I’ve got, but you don’t have any more self-respect than I’ve got. The Civil Rights Movement is over,” declared Giles, sweat glistening from his bulging forehead as he pointed angrily in the black lawmaker’s direction. “It ended when you stopped trying to help your people up, and you started trying to put me down.”

In April 2001, Mississippi voted overwhelmingly along race lines to keep the 1894 flag intact. Madison and Oktibbeha were the only majority-white counties that voted for a new flag.

Now, more than 19 years later, Mississippi lawmakers are once again contemplating retiring the 1894 flag, which voters opted to keep in that 2001 referendum by a 2-to-1 margin. Mississippi House Rep. Shanda Yates, a Democrat from Jackson, told the Mississippi Free Press Wednesday that the ongoing national and global awakening over cases of police violence against unarmed black people catalyzed serious efforts in the Legislature to whip up enough votes to rid Mississippi’s flag of the racist imagery.

Last week, thousands of Black Lives Matter activists in cities and towns all across the Magnolia State staged mass protests. That included the capital city, where thousands of residents staged the largest march since the civil rights era on Saturday, starting and ending in front of the Governor’s Mansion, where the man inside had signed a Confederate Heritage Month proclamation just weeks before.

‘I Will Vote For it in a Heartbeat’

“A group of us have always voiced support for changing the flag,” said Shanda Yates, who is white and represents a district that includes parts of Hinds and Madison counties.

“There’s obviously momentum that has been growing due to recent events with the Black Lives Matter movement, unfortunate deaths caused by police brutality. After the protest here in Jackson where the attendance was unbelievable, we felt that it would be ignorant to waste that momentum.”

Last November, she defeated Bill Denny, a white Republican who had held his seat since 1987, when she was just 6 years old. In April 2000, Denny threatened to defund the capital city after the majority-black Jackson City Council, with the mayor’s approval, voted to condemn the state flag, and Ward 3 City Councilman Kenneth Stokes took it upon himself to personally remove the flag from the Council’s chambers.

“This leaves me with no ambition to do anything at all for this city,” The Clarion-Ledger reported Denny saying in April 2000. “I have lost all respect for the entire City Hall, starting with the mayor.” Harvey Johnson Jr., Jackson’s first black mayor, was then in his first term.

The white freshman, who entered the House in January, said that other lawmakers told her that emails from constituents who favor keeping the current flag normally far outpace those from people who support changing it. Not this time, though. By Wednesday morning, the Jackson Democrat told the Mississippi Free Press that lawmakers have received about 2,000 emails over the past 48 hours.

“Most of the ones I received supported changing the flag. I can’t speak to what anyone else may have received,” she said.

Still, Yates said she is “not happy” that Mississippi Today broke the story Tuesday; she and others working to amass enough votes to pass a resolution changing the flag, which includes Republican House Speaker Philip Gunn, had hoped to have more time to woo lawmakers in rural areas before tipping off constituents who would likely try to dissuade them.

House Rep. Jeramey Anderson, a young, black lawmaker from Moss Point, told the Mississippi Free Press Wednesday that he believes Mississippians would vote to change the flag if the State held another referendum today.

But Anderson also thinks the lawmakers whom voters elected to represent them in Jackson should go ahead and do it as soon as possible. If he truly wants to, Speaker Gunn can amass enough votes in the House to pass a resolution changing the flag, the Moss Point representative said.

“We possess a lot of power here in the House and Senate. If we truly have the willpower to change the state flag, I will vote for it in a heartbeat,” he said. “And so hopefully we can see that happen in the next couple of days or weeks so Mississippi can truly show the rest of the world it is ready to move forward.”

But Mississippi Sen. Chris McDaniel, a conservative Ellisville Republican who used the 1894 flag on campaign signage during a failed 2018 U.S. Senate bid, has used social media to call in his supporters to speak out against legislators deciding the future of Mississippi’s flag.

“BREAKING NEWS: The people of Mississippi decided the flag issue using a referendum, voting by a 2-1 margin to keep the present design,” he wrote on Facebook. “At this very hour, backroom deals at your state Capitol threaten to undermine the people’s voice. If you don’t speak up now, the legislature will vote to change the flag.”

‘I Don’t Think They Have the Votes in the House, Yet’

On Wednesday afternoon, the Jones County senator told the Mississippi Free Press that he would have no problem with allowing Mississippians to vote to change the flag via a second referendum, but opposes Jackson legislators making that decision without “persuasive lengthy debate.”

“I don’t think they have the votes in the House, yet, but they are working for that endeavor. I can tell you, the same efforts are being made to find senators who would be willing to take this issue away from the people. … The people wishing to change the flag want the Legislature to make that determination,” McDaniel said.

“That’s where I’m opposed. I don’t think it’s our call to make.”

This afternoon, Democratic Sen. Derrick Simmons, a black lawmaker from Jackson, introduced a resolution to suspend the rules, which would allow the Senate to take up a vote on a bill to repeal the flag despite the fact that the legislative deadline for bringing new bills to the floor this session has already passed.

If lawmakers pushing for a new flag are unable to get enough votes to change the flag in Jackson, they could negotiate plans for a new referendum, sending it back to the voters once again.

Both Yates and Anderson want to see change come sooner, though. Anderson told the Mississippi Free Press that he thinks the current generation of Mississippi voters would opt for a new flag in 2020 if given a choice. Still, Anderson rejects the idea that people ought to accept the current flag based on a vote that happened more than 19 years ago—when he was too young to even cast a ballot.

“I truly believe that if it was on the ballot today, it would pass, but when we talk about the previous effort to change the flag in 2001, people need to understand that is no excuse to not take action on the flag right now because it is still a racially divisive,” the Gulf Coast millennial said.

Indeed, the “racially divisive” nature of the flag was on full display during the cross-state public hearings in 2000, video selections of which are available online at the American Archive of Public Broadcasting’s website.

‘I Have Been Heckled By Better Men Than You’

After Jim Giles had declared that the Civil Rights Movement was “over” at the state flag commission’s November 2000 hearing in Moorhead, the video shows him continuing to berate Blackmon, the African American representative.

“You don’t speak for all blacks in this state,” the white Southern Initiative founder told the lawmaker, drawing verbal disagreement from a black man in the crowd.

“You don’t speak for all blacks in this state,” Giles repeated, this time to the audience member. “I love black Mississippians. There are real problems blacks face that you won’t address. The prisons are overflowing, and they’re not learning in the classrooms.”

Then, Giles waxed poetic about the Mississippi flag and its alleged representation of virtues such as “gallantry,” “states’ rights,” and “valor,” before turning toward former Mississippi Gov. William Winter, a member of the commission who had made supporting racial reconciliation a priority in the years since he left office.

“Now listen, Mr. Winter. You are despicable,” Giles said. “You have been nothing but a parasite your entire career. You’re a sorry lawyer, you’re gutless, and you are worthy of being tarred and feathered and run out of this state.”

Chuckling, the then-77-year-old white former Democratic governor took the criticism in stride.

“Mr. Giles, let me say with some humor that I have been heckled by better men than you,” Winter said.

Despite his declaration of love for black Mississippians that evening, though, by 2004, Giles was openly describing himself as a “white separatist” and, amid a longshot run for political office, articulating his desire to make America white again.

“And America that I’m talking about is White America, a white nation, that’s what I’m talking about. That’s what I want. We started out a white nation; we no longer are. I want it to be a white nation again. I’m advocating separation of the races. I’m a white separatist,” he told Ayana Taylor, a black journalist, in a 2004 interview in which he also described the Iraq War as a “war for Jews.”

‘You White People Don’t Get It’

Giles was far from the only pro-1894 state-flag speaker at the fall 2000 hearings who took an aggressive, antagonistic stance toward black leaders and residents. Shortly after Giles’ outbursts at Blackmon and Winter, Mississippi Sen. David Jordan, a black legislator, pushed back against the idea that a popular vote should determine whether or not a symbol of slavery remains embeded in the flag that purports to represent more than a million black Mississippians, the Enterprise-Tocsin reported.

“Don’t tell me that you have a right to decide everything. … I am for redesigning the flag to include all of us,” Jordan said. “So I am for redesigning it because it is the right thing to do. This is a multicultural state.”

“What are you going to put on it, a watermelon?” the Indianola paper reports a heckler shouting, a reference to an old racist trope.

“I am one-eighth Cherokee Indian and am a descendant of Native Americans in northeast Mississippi. And I want to tell my black member here that my people was enslaved 200 years before your people even got here. …. This [flag] is the only thing we have left to be proud of,” one man says in a video of an Oct. 19, 2000, public hearing in Tupelo, though it is not clear from the clip which African American member of the commission he is addressing.

Video of the commission’s Oct. 26, 2000, meeting in Meridian shows two black speakers trying to convey the pain they feel when they look upon the state flag, only to be reminded of Mississippi’s history of lynching, slavery and white supremacy.

After the second black speaker, the video shows a white man in a Civil War-era Confederate cap taking the microphone, his voice cracking as he delivered an emotional plea for those in the room to honor his ancestors who shed their blood under the Confederate flag. His emotions soon gave way to anger, though, as he looked out in the crowd to the black Mississippians in the room and invoked a common Lost Cause myth that falsely claims that a significant number of free black men fought willingly for the Confederacy.

“Why does the black people ignore the free black men that fought under this banner? You people disgrace your own people,” the enraged man shouts. “Why do you turn your back on them?”

Time and again, the clips show state-flag supporters interrupting and jeering as black attendees tried to speak. In Gulfport on Nov. 9, 2000, a black man mused that he is “standing here in Jeff Davis auditorium having this conversation,” and feeling “like a Jewish person standing in Adolf Hitler Junior College in Munich, Germany.” Jefferson Davis was once president of the Confederate States of America; Mississippi has a county named after him.

“We are here in Jeff Davis, who had 5,000 people enslaved. You white people don’t get it. I’m going to ask for your empathy, not your sympathy,” the African American speaker continued. “Why is it, good white folks, that you want to incorporate something into your flag that you know offends me and him, and him—you know this.”

Instead of offering an empathetic ear, though, the next white speaker issued a general threat.

“This flag is just like my wife,” a man warned, holding up a Confederate flag. “You mess with my wife, you’re gonna get your ass kicked.” Raucous applause ensues.

‘If You Get My Flag, I Will Get Your Name’

At a commission hearing in Jackson on Nov. 13, 2000, though, abrasive white speakers faced a little more pushback.

“Who wants this flag taken down? I’ll tell you who. It’s those intent on homogenizing American culture and ridding us of the rich cultural experiences of any culture that cannot be bought, sold and controlled on Wall Street,” archive footage shows a 20-something white man in glasses saying. “These people see independent culture as a threat to our bought-and-sold national government. Having this flag makes people think about our past. This flag is dangerous to those in power because it makes us think.

“Those who want to take down the flag of Mississippi are the racists,” he continued. “They’re the ones who think so little of minorities that they love to give them handouts like affirmative action.” The man immediately drew sustained boos from the largely African American crowd for his last remark.

Later in the video of the hearing, a teenage girl with bushy orange hair and a button-up shirt with a large Confederate X across the front stepped up to the microphone and introduced herself as a grocery-store worker.

“I do work with blacks, and I have several—not just one or two—but several friends who are black,” she began. Those friends, she says, have differing views about what Mississippi should do about its flag.

“One person said, ‘Where would the slaves be today if not for slavery? They’d probably still be in Africa enslaved today if not for slavery,'” the girl offered before plowing through the ensuing chorus of groans to relay another black friend’s alleged thoughts.

“One person asked me to point out that most of the African American race living in America today got their last name from their masters,” she said. “Are you prepared to give up your last name? I don’t think you are. Because if you get my flag, I will get your name.”

“In conclusion, I say it’s time we all stand together once more and defend the honor we have left,” she continued through another round of jeering. “I also say that you will have to kill me before I will give up the honor and heritage.”

Despite the clear racial tones of the hearings, though, many newspapers across the state presented the debate as a “two sides” story, running historically sound op-eds from proponents of creating a new flag alongside op-eds from supporters of the 1894 flag that were premised on factually inaccurate claims and Lost Cause myths.

One Clarion-Ledger opinion page shortly after the April 2001 vote prominently featured assessments from two white columnists. One, Sid Salter, blamed black voters for the result, citing low turnout in the unusually timed April referendum.

“[W]hether the NAACP can digest it or not, a significant portion of the blame for the failure of the referendum that sought to change the state flag lies at the feet of black Mississippians who sat the election out and didn’t vote,” Salter wrote.

‘Even If It Does Sacrifice Some of My White Children’

In 2001, several other southern states, including Alabama and Georgia, were also discussing the possibility of shedding Confederate imagery from their flags, too. Some Mississippi pundits theorized that maybe people felt less urgency to change Mississippi’s flag in 2001 because the state adopted it in 1894 out of a genuine desire to honor Confederate veterans, many of whom were still alive.

The historical record, though, suggests otherwise.

Mississippi radically remade its Constitution in 1890 with the goal of disenfranchising black voters, implementing a system of Jim Crow laws that included literacy tests and poll taxes, seeking to kill off reforms the North had insisted on in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era.

In a convention hall where state officials plotted out the new constitution that September, one state lawmaker, J.H. McGehee from Franklin County, ” gave a rousing speech to his fellow lawmakers’ delight.

“I will agree that this is a government by the people and for the people, but what people? When this declaration was made by our forefathers, it was for the Anglo-Saxon people. That is what we are here for today—to secure the supremacy of the white race,” he said.

To guarantee black disenfranchisement, McGehee said, he was willing to risk disenfranchising some white people, too, noting proposals that would have required people to own property or have a certain level of education before they could vote.

“I will vote for an educational or property qualification if necessary, even if it does sacrifice some of my white children, or my white neighbors or their children,” the lawmaker said. “Too many are trying to whip the devil ’round the stump.”

McGehee then sought to shame his colleagues for not showing more willingness to sacrifice some white people’s rights in the name of white supremacy. He highlighted the sacrifices of a veteran in the room.

“The gentleman from Webster, Mr. (John E.) Gore, was willing to risk his life for four long years—was willing to fight for his country, for property and all that, and yet he and men who had no property were not willing to sacrifice a single vote to save this country from negro domination,” McGehee said.

“Thousands of the gallant sons of the South had no property in slaves or otherwise, and yet they offered their lives to protect their neighbor’s property, and the same noble spirit is now ready for any concession or sacrifice that will secure and perpetuate white supremacy in Mississippi.”

The lawmaker’s speech drew “great and long continued applause” from his colleagues, The Clarion-Ledger wrote then.

Ten years later, the future governor James Kimble Vardaman would bluntly offer his own assessment of the 1890 Constitution’s purpose: “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. Mississippi’s constitutional convention was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the n*gger from politics; not the ignorant—but the n*gger,” said Vardaman, who was known as “The Great White Chief” for his steadfast defense of white supremacy.

‘Legal and Lasting’ Odes to ‘The Lost Cause’

In the meantime, Vardaman and other lawmakers continued working to undo Reconstructionist reforms, and to further cement white supremacy both symbolically and systematically. In 1894, Gov. John Marshall Stone, a Confederate veteran, sent a message to the Legislature, where Vardaman was then serving as speaker of the House. The governor asked lawmakers to devise a new state flag and coat of arms. Two weeks later, the Joint Legislative Committee for a State Flag sent a bill to his desk and he quickly signed it into law, approving a flag that Mayersville Sen. E.N. Scudder designed.

Years later, at the annual convention for the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s Mississippi Convention, Scudder’s daughter explained her father’s design.

“My father loved the memory of the valor and courage of those brave men who wore the gray…. He told me that it was a simple matter for him to design the flag because he wanted to perpetuate in a legal and lasting way that dear battle flag under which so many of our people had so gloriously fought,” Fayssoux Scudder Corneil told the organization, which spent much of the early 20th century rewriting Civil War history with Lost Cause myths and erecting Confederate monuments across the South.

But merely honoring Confederate veterans likely was not legislators’ primary goal in 1894; the same week lawmakers created the new flag design, they defeated a proposal that would have established a soldier’s home for aging, ailing and homeless Confederate veterans.

“Timid souls at the North who still cherish fears that ‘The Lost Cause’ has a dangerous hold upon the Southern people ought to be reassured by the recent action of the Mississippi House in defeating, by an overwhelming majority, a proposition to establish a home for infirm and helpless Confederate veterans,” the New York Evening Post wrote in a blistering editorial.

The Clarion-Ledger defended lawmakers’ decision in a Feb. 8 editorial.

“‘The Lost Cause’ has never had a ‘dangerous hold’ upon the South …, but her Northern brethren, timid or otherwise, should not be permitted to think for a moment that Mississippi has lost her love and sentiment for the old soldier,” the Ledger wrote. “The building of a ‘soldier’s home’ was deferred on account of hard times, because all the money at the command of the State will be needed for other and more pressing purposes, such as maintaining our excellent public school system [and the] establishment of a State prison farm, etc.”

Lawmakers purchased the Parchman Plantation six years later, establishing the now infamous Mississippi State Penitentiary originally as an all-black prison, clearly modeled after the massive antebellum plantation it replaced. Gov. Vardaman described Parchman as running “like an efficient slave plantation” that would provide black men with “proper discipline, strong work habits, and respect for white authority.”

With black laborers working cotton fields that stretched for miles, Parchman, like the Mississippi flag, provided a stark visual reminder that the Confederate South’s legacy lived on.

Push for a New Flag Begins

The state flag provoked few challenges during most of the century that followed, with no major outcry until the decades after the Civil Rights Movement achieved success in overturning much of the Old South’s Jim Crow legal structure. As recently as the early 1980s, the Mississippi NAACP remained split on whether or not it was worth fighting for a new, less offensive symbol.

Stuart Stevens, a longtime Republican strategist from Jackson who served as an adviser for Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential run and is now working for the anti-Trump Lincoln Project this year, recalled the ubiquity of the Confederate flag when he was a student at the University of Mississippi, where the UM side of the football stadium was awash in tiny rebel flags.

“I went to games where they unveiled the second largest Confederate flag in the country, and I always wondered what the largest was,” said Stevens who, nevertheless, supports changing the state flag. (Stevens is also a member of the Mississippi Free Press Advisory Board).

But John Hawkins, the University of Mississippi’s first black cheerleader, forced the issue of flags and Confederate imagery in 1983 when he refused to partake in the tradition of carrying and distributing rebel flags at Ole Miss football games, leading the university to eventually ban the ubiquitous flag from its official sports festivities.

Concerns over the state flag’s own Confederate imagery soon bubbled to the surface. In 1988, then Mississippi House Rep. Aaron Henry, a longtime NAACP leader with a storied civil rights legacy, introduced his first bill to repeal the Mississippi flag. The House never brought it to the floor for a vote, even though Henry reintroduced it twice more in 1990 and 1992.

In 1993, the Mississippi NAACP filed a lawsuit, arguing that the flag violated Mississippians’ constitutional rights “to free speech and expression, due process and equal protection as guaranteed by the Mississippi Constitution.”

After a lower court dismissed the suit, the NAACP appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court, where, in 2000, the state’s top judges discovered an unexpected twist: Unbeknownst to state officials for nearly a century, apparently there was no official state flag; lawmakers, in an apparent oversight, had nixed the flag when it revamped the state code in 1906 when they failed to include the state flag and coat of arms sections in the new version.

Still, the State’s high court agreed with the lower court that the NAACP had no case because the flag, while offensive, “does not deprive any citizen of any constitutionally protected right.”

The discovery that Mississippi in fact had no official flag prompted Gov. Musgrove’s decision to appoint his state flag commission, since simply re-adopting the old design at the turn of the century was a non-starter for many. Issues of racism and the State’s vicious past were at the forefront in the Magnolia State, which proportionally has the largest black population in the U.S. and the most black elected officials per capita.

Pro-Flag Group Warned Voters Against ‘Cultural Genocide’

In 2000, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson led a march down a country road in Kokomo, Miss., where many residents doubted the official story that 17-year-old Raynard Johnson had hung himself. His father had stepped out on his front porch one June morning that year to find his teenage son hanging from a tree, a waist belt tied around his neck.

Doubts over whether or not Johnson committed suicide kick-started a federal investigation that turned up no evidence of foul play, but Jackson said it evoked memories of Mississippi’s lynching of hundreds of black men and boys over their alleged interactions with white women, like 14-year-old Emmett Till who a group of white men murdered in Money, Miss., after a white woman accused him of whistling at her. At West Marion High School, Johnson had a reputation for befriending and dating white girls.

The ghosts of Mississippi’s racist past were already swirling the year before in 1999, when state leaders, including then-Sen. Trent Lott, provoked national controversy amid revelations about their ties to the Council of Conservative Citizens, a white supremacist group based in Carrollton, Miss., that sought to carry on the legacy of the then-defunct Citizens Council, which published long lists of black-on-white crimes to scare white Americans.

The earlier council was a segregationist organization that fought school integration and other forms of desegregation, and had a reputation as the “uptown Klan,” as Mississippi newspaper editor Hodding Carter Jr. called it, because they fashioned themselves a few pegs above their sheeted brethren on the hierarchy of professional racism.

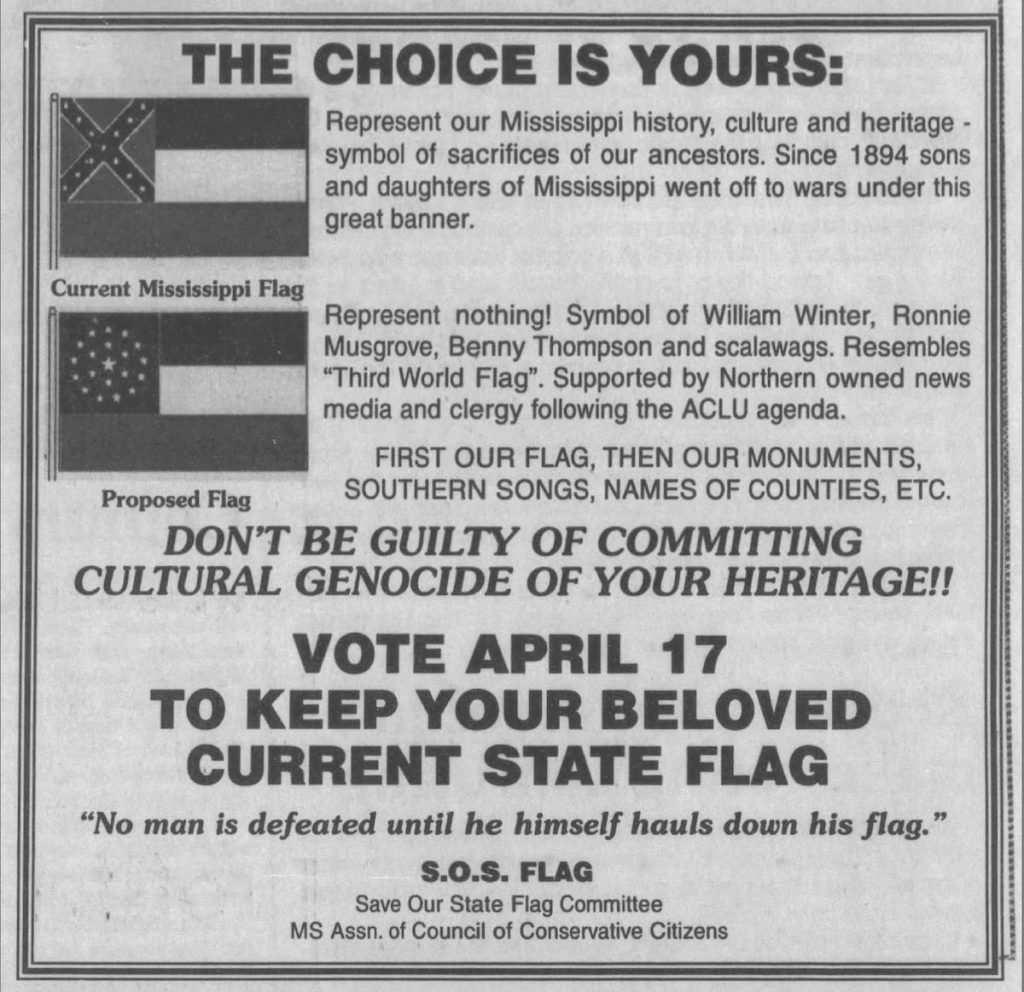

The later group played a significant role in the 2001 state flag referendum. Members, including Conservative Council leader Bill Lord, spoke up against changing the flag and berated members of Gov. Musgrove’s commission in 2000. The Council also raised $2,800 through its Save Our State Flag Committee (referred to as S.O.S.) to run ads urging voters to defeat the effort to change the flag.

One of the group’s S.O.S. ads told voters they had a “choice.” They could keep the 1894 flag, and “represent our Mississippi history, culture and heritage,” or choose the proposed flag—the “symbol of William Winter, Ronnie Musgrove, Benny [sic] Thompson and scalawags.”

Rep. Bennie Thompson is Mississippi’s lone black member serving in either chamber of the U.S. Congress, serving in the majority black Second Congressional District, which runs along the Delta. White supremacist Democrats first created a Delta district in the years following Reconstruction in order to ensure five other majority white districts—an act of gerrymandering that diminished black voting power outside the Delta.

In its 2001 ad, the Council’s S.O.S. campaign claimed the proposed new flag “resembles [a] ‘Third World’ Flag” and was “supported by Northern owned news media and clergy following the ACLU agenda.” If the state should change its flag, it continued, monuments, southern songs, and names of counties would be next.

Mississippi has several counties named after prominent Confederates and white supremacists, including Forrest County, where Hattiesburg is the county seat, which is named for a Ku Klux Klan founder, and Jefferson Davis County, after the Confederate president and former Mississippi U.S. senator.

“Don’t be guilty of commiting cultural genocide of your heritage!!” admonished the Council’s 2001 ad. In recent decades, white supremacist groups have often framed efforts at greater social equality and inclusion, such as the removal of racist historical symbols, as attempts at “white genocide.” The “genocide” theme drew national attention in 2016 when then-presidential candidate Donald Trump retweeted a supporter with the username “WhiteGenocideTM” whose Twitter bio listed their location as “Jewmerica” and linked to a website featuring a pro-Adolf Hitler documentary.

In the years since the 2001 referendum, various local and county leaders have begun removing the state flag despite lack of an official repeal. After a white gunman with an affinity for the Confederate flag massacred nine black members inside a Charleston, S.C., church in 2015, that state’s legislative body voted to remove the Confederate flag that still flew on the South Carolina capitol grounds. In fact, Dylann Roof had posed with a photo of the Confederate flag and, in his manifesto cited the Council of Conservative Citizens as inspiration and used racial-superiority language similar to that of McGehee during the 1890 debate on the new flag.

In Mississippi, a number of towns and counties removed the state flag from its flag poles in 2015, citing the painful message it sent to African American residents even as the scourge of racism clearly continued to thrive. A number of white state officials, including then-Attorney General Jim Hood, a Democrat, and House Speaker Philip Gunn, a Republican, publicly voiced support for changing the flag.

Colleges and universities, including the University of Mississippi and the University of Southern Mississippi, also took down the state flag that year, with USM hoisting in its place and in place of the school flag a second and third American flag. Every Sunday since, a group of out-of-town pro-state flag protesters, the Delta Flaggers, have planted themselves under the American flags at USM’s entrance, where they wave state flags and, since the 2016 election, Trump flags.

Many flag supporters also cite Dylann Roof’s massacre—but for making it more difficult to display the flag.

‘No Symbol or Flag … Made Him Evil’

After neo-Nazis, klansmen, and other torch-carrying white supremacists marched violently on Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, where one killed white anti-racism activist Heather Heyer, Mississippi saw another burst of activists seeking the flag’s removal. A chaotic scene unfolded in Hattiesburg at the University of Southern Mississippi the day after the violence up north, as a grassroots group of Black Lives Matter activists joined the Delta Flaggers at USM’s entrance. The dueling protests went on for weeks, with university police requiring the two groups to protest from opposite sides of the gate.

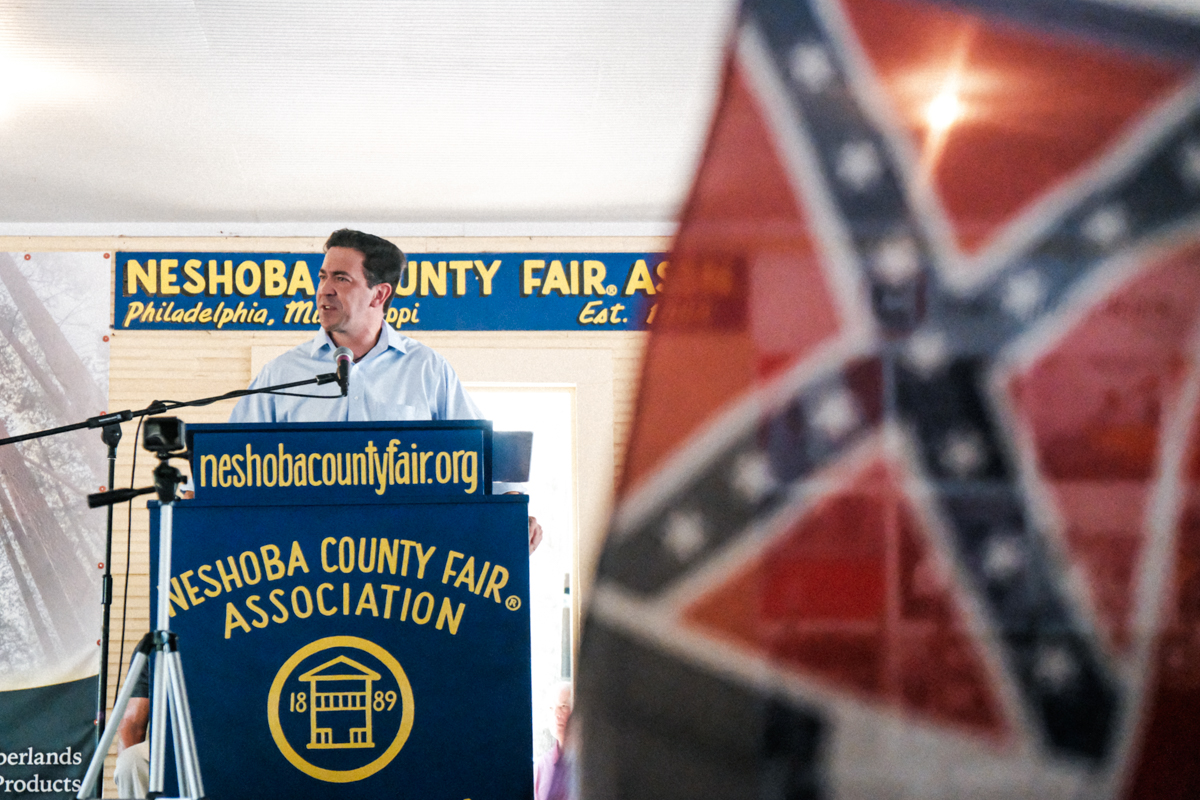

Other pro-Mississippi flag groups and voters sought to cow legislators in the middle of the last decade, though, threatening to boot them from office if they embraced the idea of designing a new flag. At the Neshoba County Fair in July 2015, just a month after Speaker Gunn declared that the current flag “needs to be removed,” hundreds of prospective voters waved miniature state flags as Mississippi officials spoke. As Gunn walked up to the stage to speak, members of the crowd wave signs reading, “Keep the Flag, Change the Speaker.”

In the wake of the Charleston church massacre, though, then-Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, who already had his sights on the governor’s mansion, scored points with pro-flag voters when he responded to Gunn’s announcement with an implicit swipe at his own party’s speaker.

“No symbol or flag or Web site or book or movie made him evil,” Reeves tweeted in June 2015, referring to the shooter, Dylann Roof, whose social media posts featured him waving Confederate flags, holding guns, and burning American flags.

During his gubernatorial run last year, Reeves drew scrutiny for his participation as a Millsaps College student in a fraternity whose members at the time he was there were known for their Old South Balls, idolizing of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, wearing black face, and for racist incidents involving black students. His Democratic opponent, Jim Hood, also raised eyebrows because members of his fraternity at the University of Mississippi also wore black face. Both men denied ever wearing racist costumes themselves, though.

As governor, Reeves again attracted accusations of, at best, insensitivity to black Mississippians if not outright racism when he followed his predecessor’s tradition of proclaiming “Confederate Heritage Month” on behalf of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The organization, to whom he gave a keynote address in front of a massive Confederate flag at their 2013 annual reunion, has devoted itself to rewriting the history of the Civil War to cast the Confederacy as a noble entity fighting federal oppression and for state’s rights, not slavery.

Such attempts to whitewash the Confederacy are at odds with the historical record, including the 1860 Mississippi Declaration of Secession, which said its decision to secede was “thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world.”

The 2020 effort to change Mississippi’s state flag once again followed national events after the recent spate of high-profile deaths of black men and women prompted a worldwide explosion in protests over police brutality and racism in law enforcement.

‘There’s Just Nothing Good About the Flag’

Changing the flag in the midst of the largest civil-rights protests since the 1960s would be meaningful, Stuart Stevens told the Mississippi Free Press, but “there’s also the flip side of that,” he said.

“What does it say if you don’t change it? It’s sort of like how (Democratic presidential nominee) Joe Biden is looking at a running mate. And what is it going to say if he doesn’t pick an African American?” he said, referencing party activists’ push for the 78-year-old white candidate to pick a black woman as his vice presidential nominee, such as U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris or U.S. House Rep. Val Demings.

“There’s just nothing good about the flag. Nobody is sitting there in a corporate headquarters thinking about opening a corporate branch, and they’re going to be more likely to do it if we don’t change the flag. It just isn’t going to happen,” Stevens continued. “Now how much good will it do? You never know these things. All you can do is try to move forward positively. But would it help Mississippi’s image? Yes.”

Mississippi has a chance to cast off its own racism, he said, and removing a racist symbol from atop its flagpoles would be a “tremendously positive” first step, Stevens said. He never thought much about the flag one way or the other, he admitted, until later in life when African American friends shared “just how painful it was to them.”

“I’m a seventh-generation named for an uncle who rode with (Confederate Gen.) Jeb Stuart. But this whole glorification of the Lost Cause in the South is a travesty,” Stevens said. “I mean, I grew up studying Robert E. Lee, but never Ida Wells. There’s something really wrong now. And we have to come around to addressing reality that the Civil War was a bunch of traitors who believed in slavery. … Why have a state flag that is so painful to so many? We are the most African-American state in the country. Why not do everything we can to make sure African Americans feel more like they are a part of the state?”

He pointed to Germany’s emergence from the Second World War and the Nazi regime. Unlike the post-Civil War South’s glorifying of the Confederacy, post-Holocaust Germany did not erect monuments to the likes of Adolf Hitler or his Nazi generals, and banned the production and display of Nazi symbols, including the flag of the Third Reich. Barred from waving the Nazi flag, some German white supremacists in the decades since have instead waved Confederate flags. The South, and America as a whole, could take a page out of Germany’s book, he suggested.

“If Germany can come to grips with its history, the South can come to grips with its history, too.”