After Mississippi’s Legislature amended the state constitution in 1890, white supremacist Missisippi House Rep. James K. Vardaman was not shy about declaring its purpose in the post-Reconstruction landscape.

“There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. Mississippi’s constitutional convention was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the n*gger from politics—not the ignorant, but the n*gger,” said Vardaman, the Democrat known as Mississippi’s “Great White Chief,” who served as speaker of the Mississippi House and, later, as a governor and U.S. senator.

The new Jim Crow constitution steamrolled civil rights and voting-rights gains Black Mississippians had made in the years during the Civil War and slavery’s end. Decades later, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act ended many of its provisions, such as literacy tests and poll taxes for voting.

On Election Day, Mississippi voters have the opportunity to vote to rid the state constitution of a remnant that still remains from the one Vardaman helped design: A state-level elections law similar to the national electoral college system that requires candidates for eight statewide offices, including governor, to win not only the popular vote, but a majority of House districts.

Under the system, if a candidate does not win both the popular vote and a majority of House of Representative districts, the Mississippi House decides the winner.

‘Minimizes African American Voting Strength’

When the Jim Crow constitution was crafted in 1890, Black Mississippians accounted for a majority of the state. If Black men had been able to overcome other Jim Crow provisions and exercise the right to vote, the system would have ensured white Mississippians still maintained power over the state’s top leaders; white Mississippians represented a majority in most house districts at the time.

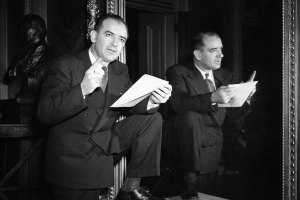

A campaign of government-sanctioned racial terror, intimidation tactics and the other Jim Crow provisions made the provision moot, however. The provision did come into play in 1999, however, when Democrat Ronnie Musgrove won the popular vote for governor, but not a majority of House districts. But Democrats still held a strong majority in the Mississippi House, which declared Musgrove the winner.

The law became a flashpoint in last year’s statewide elections, though, when then-Attorney General Jim Hood, a Democrat, mounted a close race for the top job against then-Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, who ultimately won in an election where all statewide winners were Republican. Democrats worried that, if Hood had won the popular vote but not a majority of House districts, the House, which now has a Republican supermajority, would have declared Reeves the victor anyway.

A group of Mississippians challenged the law in federal court last year with assistance from former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder’s National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

In legal filings, the plaintiffs argued that the state constitution’s electoral scheme “minimizes African-American voting strength, and most glaringly, it requires an African-American-preferred candidate to win at least 55 percent of the popular vote in order to win a majority of House districts, while a white-preferred candidate can accomplish the same feat with only 45 percent of the popular vote.”

Mississippi’s system took inspiration from the national electoral college, which was advocated by slaveholding states when the founding fathers drafted the U.S. Constitution. At the federal convention in July 1787, James Madison said he would prefer a popular vote—if not for southern resistance to the idea.

“There was one difficulty, however, of a serious nature attending an immediate choice by the people,” he wrote, referring to a popular vote to choose presidents. “The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of Negroes. The substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to the fewest objections.”

U.S. District Court Chief Judge Daniel Jordan punted on the question last year, saying he would give the Mississippi Legislature a chance to address the Jim Crow provision first.

‘That’s Got to Change’

Mississippi Secretary of State Michael Watson, Mississippi’s top election official, urged the Legislature to put the issue on the ballot, and it did so.

“I’m definitely supportive of moving away from the current system. We’re the only ones that do it (like this), and that’s got to change,” Watson, a Republican, told The Clarion-Ledger last year.

When Mississippians vote on Tuesday, the option to amend the Mississippi State Constitution to rid it of the Jim Crow election law will appear as the second-to-last item on the ballot.

“This amendment provides that to be elected Governor, or to any other statewide office, a candidate must receive a majority of the votes in the general election. If no candidate receives a majority of the votes, then a runoff election shall be held as provided by general law. The requirement of receiving the most votes in a majority of Mississippi House of Representatives districts is removed,” the amendment provides.

Voters can vote “Yes” to adopt the amendment and remove the Jim Crow election law or “No” to keep it in place.

New State Flag on Ballot

The final item on the ballot gives Mississippians the option to adopt a new state-flag design, which a commission designed after the Legislature voted to retire the old Confederate-themed state flag during the summer.

The old flag, adopted in 1894 when Vardaman was speaker of the House, was another effort to solidify white supremacy government after the end of Reconstruction. Large majorities in both chambers of the Mississippi House and Senate voted to get rid of it and begin the search for a new flag amid the nationwide racial reckoning that also swept through Mississippi this year.

The election is Tuesday, Nov. 3. Mississippi voters who did not vote by absentee ballot must arrive at their polling places with a valid form of photo ID to cast a ballot. Mississippi State Health Officer Dr. Thomas Dobbs has advised voters to wear masks amid the COVID-19 pandemic, though election officials are only requiring them for poll workers. More information on voting is available at sos.ms.gov/vote.

This story is part of the MFP’s Mississippi Trusted Elections Project, focusing on access to the polls and voting access in Mississippi. Visit the site to view several infographics and continually updated maps of voting precincts, absentee vote totals and precinct changes across Mississippi, created by William Pittman. The American Press Institute provided funding for this work.