Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves signed “a law to turn a page in Mississippi today,” as he put his signature on legislation that will retire the state’s Confederate-themed flag. With legislative officials and African American leaders surrounding him, the Republican governor said that recent events have changed his mind about what the State of Mississippi should do about the long-controversial symbol.

“Over the last several weeks, I have repeatedly heard it said that we must have change because ‘the eyes of the nation’ were on Mississippi. Frankly, I’m not all that concerned about the eyes of the nation,” Reeves said during the 5 p.m. speech at the governor’s mansion in Downtown Jackson. “I do care, however, about looking in the eyes of every one of my neighbors—and making sure they know that their state recognizes the equal dignity and honor they possess as a child of the South, a child of Mississippi, and yes, as a child of an Almighty God.”

U.S. House Rep. Bennie Thompson, the only Black member of Mississippi’s congressional delegation, praised today’s bill signing, but said there is more to do.

“I commend the state Legislature on doing what is right. Now the question is, what else will we do?” the Mississippi Democrat said in a statement this evening. “We cannot stop at changing the flag. This is only a symbolic change. I hope we see this moment as an opportunity to address systemic problems in our state.”

A renewed push to change the flag came amid protests around the state—and throughout the nation—over systemic racism, sparked by the police killings of African Americans like George Floyd in Minnesota and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky.

Earlier this month, a multiracial and student-organized group of protesters staged the largest march in downtown Jackson since the civil rights era.

‘It Sounds Like Mississippians’

During his address, the governor alluded to protests outside Mississippi, where some activists have toppled statues that honored Confederate figures. Mississippi has dozens of Confederate monuments and memorials on public spaces across the state, too, which the Mississippi Free Press is tracking with an interactive map.

But Mississippians need not worry that the state’s history will be “erased,” Gov. Reeves said today, vowing to “protect Mississippi from that dangerous outcome.”

“It is fashionable in some quarters to say our ancestors were all evil. I reject that notion. I also reject the elitist worldview that these United States are anything but the greatest nation in the history of mankind,” Reeves said. “I reject the mobs tearing down statues of our history—north and south, Union and Confederate, founding fathers and veterans. I reject the chaos and lawlessness, and I am proud it has not happened in our state.”

A number of national protests over the past month grew violent, at times with police provoking peaceful protesters by firing rubber bullets or tear gas into previously peaceful crowds.

While a reckoning on race and white supremacy spread across the country, supporters of changing the flag sought to whip votes throughout June to change the flag—which a white supremacist Legislature created in 1894 as the state dramatically rolled back rights Black Mississippians gained after emancipation. Over the weekend, a veto-proof majority of lawmakers in both chambers of the Republican-dominated Mississippi Legislature voted to retire the current state flag.

On the Senate floor on Saturday, Sen. Barbara Blackmon, a Black Democrat from Jackson, recalled tears turning into icicles on her face one frosty cold January day in Washington, D.C., as she watched Barack Obama take the oath of office.

“Just as I thought I would never live to see a Barack Obama, I thought I would never live to see this flag come down,” she said.

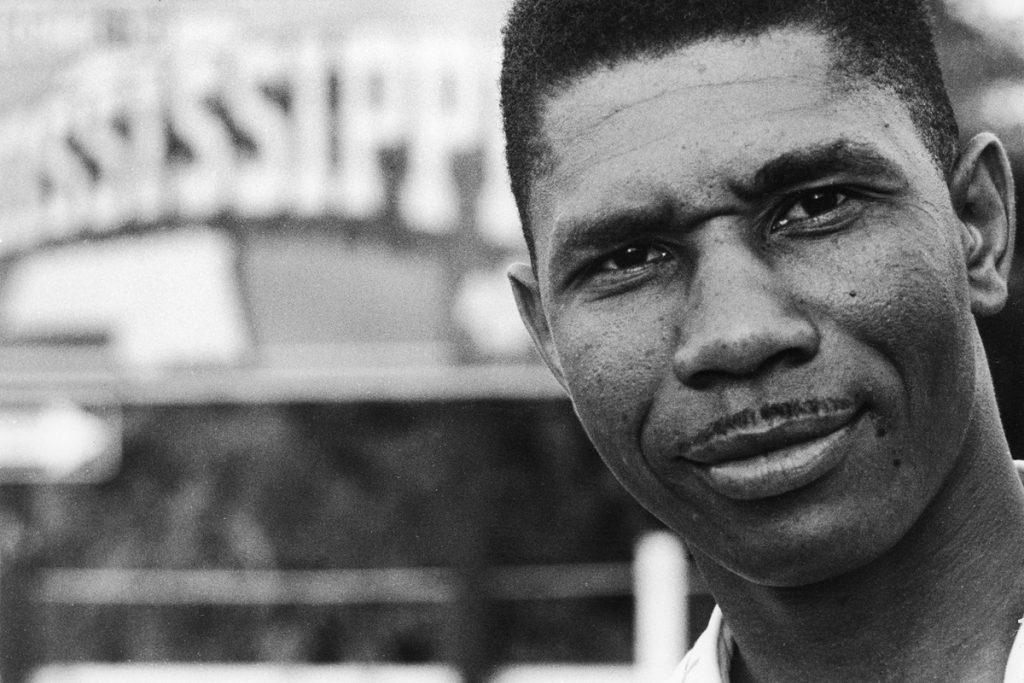

As Gov. Reeves spoke in the governor’s mansion today, Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute Executive Director Reena Evers-Everette (who is a member of the Mississippi Free Press advisory board) sat in the front row, wearing a black mask with “EVERS” written in white across it. In 1963, she and her siblings were inside their Jackson home with their mother, Myrlie Evers, when they heard their father, NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers, pull into the driveway. Moments later, as he was getting out of the car, a white supremacist shot him in the back. A local hospital initially refused him entry because of his skin color, but admitted him after learning his identity. He died there 50 minutes later.

Gov. Reeves, who is white, was born 11 years later. He grew up in Florence, an 85% white Rankin County town about a dozen miles southeast from the capital city, which is 82% Black. During today’s speech, he acknowledged that his experiences had colored his worldview, shielding him from having to reckon with the pain that having a flag with an emblem of the Confederacy flying atop state government buildings caused African Americans.

Even before the final push to change the flag began, Gov. Reeves drew criticism for proclaiming Confederate Heritage Month in April at the request of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization known for whitewashing the history of the South’s role in the Civil War. In 2013, he spoke to the SCV’s national reunion in Vicksburg, Miss., with a massive Confederate flag hanging behind him and arrangements of cotton on either side. And as a college student in the 1990s, Reeves was in a college fraternity known for romanticizing the slaveholding South, wearing blackface (he has denied he ever participated), and idolizing Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Today, though, Reeves sounded a note of understanding as he spoke about “reconciliation.”

“Now, I can admit that as a young boy growing up in Florence, I couldn’t have understood the pain that some of our neighbors felt when they looked at our flag—a pain that made many feel unwelcome and unwanted,” Reeves said. “Today, I hear their hurt. It sounds different than the outrage we see on cable TV in other places. It sounds like Mississippians, our friends and our neighbors, asking to be understood.”

‘End This Battle Now’

The late Mississippi House Rep. Aaron Henry, who was a friend of Medgar Evers and was the NAACP president at the time of his death, introduced numerous bills in the 1980s and 1990s to change the flag, but they never made it to the floor for a vote. In 2001, Mississippians voted 2-to-1 in a referendum to keep the 1894 flag.

Until recent weeks, Reeves and other Republicans publicly said they thought the flag should only change if Mississippi voters choose to change it in another referendum.

“I’ve long believed the better path towards reconciliation for our state would be for the people to retire this symbol on their own at the ballot box,” Reeves continued. “And I believe we would have eventually chosen that outcome—a deliberate consensus by a thoughtful people. I am not a man who likes to change his mind. But through prison riots, Easter tornadoes, a pandemic the likes of which we haven’t seen in over 100 years and now this flag fight, all in just a few months, I have taken to replacing sleeping with praying.”

The numerous crises unfolding in the state and throughout the nation, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crash changed his mind about changing the flag, Reeves said, and he feared further ruptures in the state’s social fabric.

The 2001 vote on the state flag came following tumultuous public hearings where Black speakers and public officials often became the target of vicious, angry, racist rants. Mississippians at the time voted 2-to-1 to keep the 1894 flag.

“Our economy is on the edge of a cliff. Many lives depend on us cooperating and being careful to protect one another. I concluded our state has too much adversity to survive a bitter fight of brother against brother,” Reeves said today. “We must work to defeat the virus and the recession—and not be focused on trying to defeat each other. So last week, as the Legislature deadlocked, the fight intensified, and I looked down the barrel of months of more division—I knew that our path forward was to end this battle now.”

Reeves first announced that he would sign the bill if it made it to his desk on Saturday, as more than two-thirds of lawmakers in both legislative chambers coalesced in support of the effort.

‘Finally Free of This Heinous Symbol’

After the bill signing ceremony, the Mississippi Center for Justice, a non-profit law firm that focuses on civil rights issues, praised it as “cause for celebration.”

“For decades, our state has been represented by a symbol that celebrates the degradation and brutalization of Black people,” MCJ CEO and President Vangela M. Wade said in a statement this evening. “It has taken far too long, but our flag will finally be free of this heinous symbol of hatred and oppression.”

Like Congressman Thompson, Wade said the state must “take courageous action” to address other systemic issues of “pervasive” racial injustice and discrimination.

“Removing the flag must be accompanied by ensuring health care, education, and economic opportunity for the marginalized and the poor of this state,” Wade said.

Now that Reeves has signed the bill into law, the state flag must come off all government flagpoles within 15 days. Gov. Reeves, Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and Mississippi House Speaker Philip Gunn will each appoint three members to a committee that will design a new flag, which it will submit to the governor in September.

The law includes two stipulations: the committee must design a flag without the Confederate emblem and must include the words, “In God We Trust,” which is already on the Mississippi State Seal. Voters can choose to accept or reject the committee’s design in November’s election.