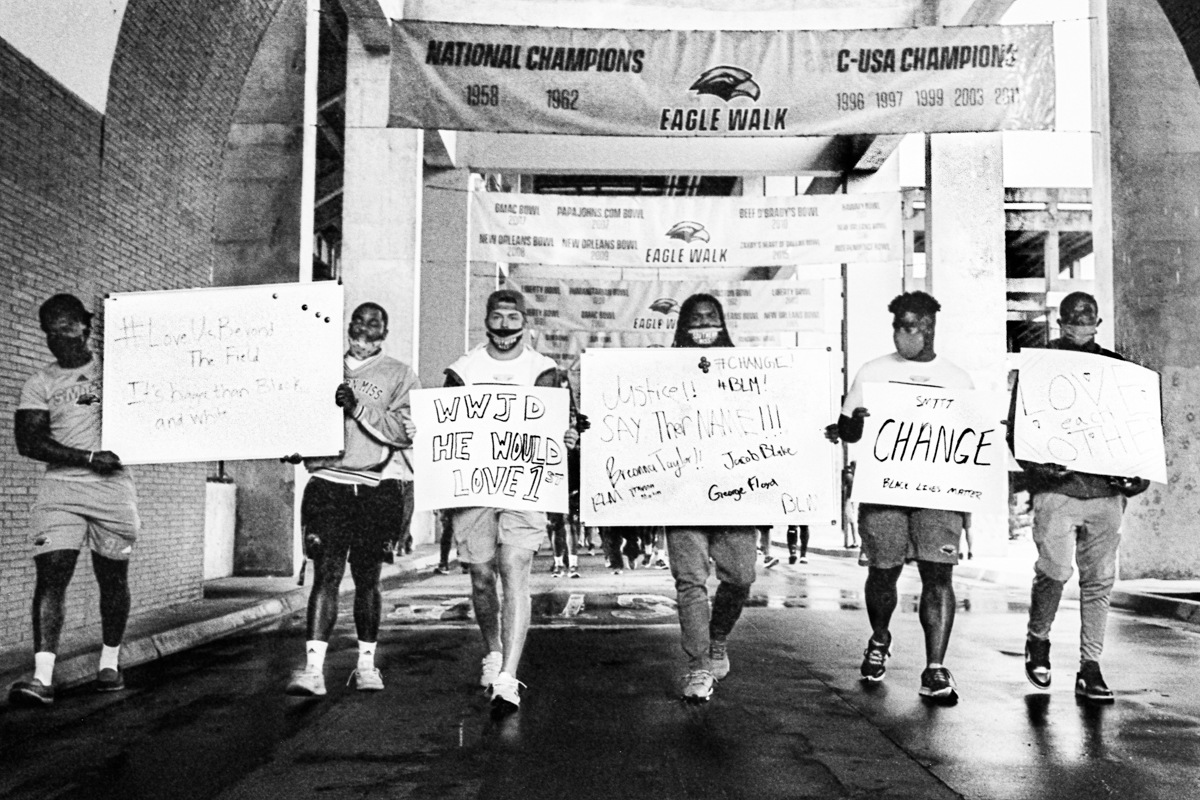

HATTIESBURG, Miss.—“Black Lives Matter,” the University of Southern Mississippi football team chanted as the entire group, backed by coaches and staff, marched out of Friday’s planned practice and to the front of campus to protest racial injustice. Dozens of mask-wearing fellow USM students and local residents joined them.

“Black people are not getting justice like everyone else, and that’s a problem,” Golden Eagles defensive lineman Eriq Kitchens, who is Black and from Batesville, Miss., told the Mississippi Free Press.

Protests and marches over police killings of unarmed Black people have churned all summer long in Hattiesburg, across Mississippi and throughout the United States. After a video emerged showing police in Kenosha, Wash., shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, athletes nationwide joined marches and walkouts, including the football teams at Mississippi State University on Thursday and the University of Mississippi on Friday morning.

On Friday morning, the USM team announced in a social-media statement that they, too, planned to stage a walkout march during their planned 5 p.m. practice time.

“We live by a brotherhood. … We cannot be silent to instances of racial injustice in our country any longer,” the Aug. 28 statement read.

Head Coach Jay Hopson tweeted a message of support shortly after.

“We as a Coaching Staff fully support our players in a march against social injustice,” he wrote.

Southern Miss linebacker Swayze Bozeman, a white Wesson, Miss., native, said he was there to show support for the teammates he considers his “family.”

“For us, football isn’t everything. Football is what we do. It’s not who we are. So we just wanted to take this opportunity to make a positive impact on our campus, on our team, around Hattiesburg, and to show our support for the Black community, because it’s all about love.”

He held a sign that read, “WWJD? He Would Love First.”

“And so that’s what this is about. We’re trying to show love. And when we love, things get fixed,” Bozeman said.

‘My Family is Being Persecuted’

After the march from the stadium to the front of the Forrest County campus, defensive lineman Eriq Kitchen stood on the sidewalk next to Bozeman, with both men holding protest signs as cars passed the front of USM’s campus on Hardy Street, many honking in approval.

“Black people are not getting justice like everyone else, and that’s a problem. We try to stress brotherhood here. It’s sickening because me and my good friend right here, Swayze, I call him my brother,” Kitchen said, gesturing toward his white teammate. “And people in America, they don’t take time to learn about somebody. They want to look at color. Me, as a Black male, it’s hard for me to watch and not say anything, and brothers like Swayze—brothers who are not Black—they’re here to support us. It’s sad right now, but we’re here to make changes.”

Before he came to USM, Bozeman was the only white defensive player on the football team at Copiah-Lincoln Community College. He said he has always supported Black Lives Matter, but that is not the only reason he decided to march.

“This is my brother,” he said, referring to Kitchen. “We may look different, but that’s my brother. And the rest of my team, those are my brothers. If my brothers hurt, I hurt. So for me, it’s not just a Black Lives Matter thing. It’s my family. My family is being persecuted. My family is hurting. So it’d be wrong of me not to support my family. … It’s never just been Black Lives Matter—it’s been, I love my brothers.”

Dozens of supportive students, including other USM athletes, and Hattiesburg community members flanked the Golden Eagles team Friday evening as they marched out of the Athletics Center, which sits on the north endzone of the football field.

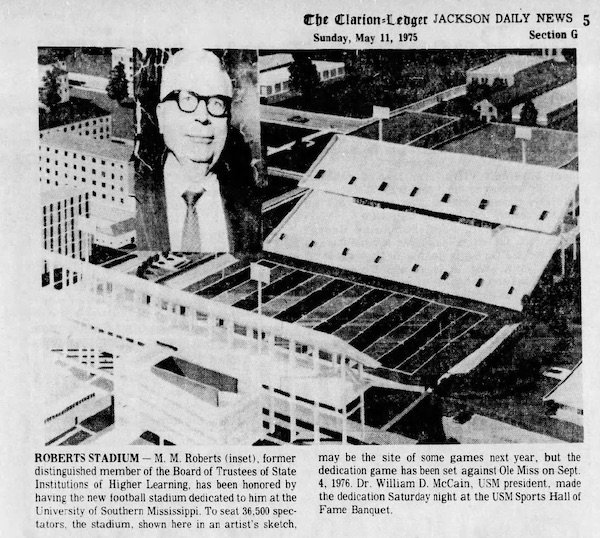

But racism taints even the name of the field where the team plays and the stadium that surrounds it, which fans call “The Rock.” The stadium’s formal name is the M.M. Roberts Stadium, after Malcom Mette Roberts, an alumnus who served as the president of the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning from 1960 until 1972. He was also an unapologetic racist who made no effort to hide his resistance to integration.

‘The Good Lord Was the Original Segregationist’

After graduating from USM in 1918, when it was called the Mississippi Normal College, Roberts pursued a law degree at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, where he graduated with Ross Barnett in 1926.

When voters elected Barnett, a Dixiecrat, as Mississippi’s governor almost 34 years later, Roberts quickly worked to install reliable opponents of racial equality throughout the state government. The new governor was a Baptist Sunday school teacher who claimed that “the good Lord was the original segregationist.”

Gov. Barnett packed the IHL Board of Trustees with racists in his first year, including Roberts as its new president. Roberts took his task seriously, voting in 1963 to withhold a degree from James Meredith—the first Black student admitted to the University of Mississippi in Oxford. Three years earlier, Barnett had sought to block Meredith, a Kosciusko, Miss., native, from entering UM at all.

Roberts was willing to deny Meredith the diploma he had rightfully earned, even though some members feared the federal courts would respond by stripping Mississippi’s universities and colleges of accreditation. A bare 6-to-5 IHL majority opposed the move, though, but mostly out of fear of the repercussions. That same year, Roberts worked with the racist Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, which was attempting to have UM Professor James Silver fired for speaking out against Mississippi’s racist “closed society.”

Even after Barnett’s term expired in 1965, his hand-picked IHL president continued to wage an anti-civil rights crusade. In 1966, Roberts wrote and the IHL passed a policy that became known as the “Aaron Henry speaker ban,” referring to the state NAACP president at the time who had spoken at Mississippi State University that same day. It ordered universities and colleges not to invite “speakers who will do violence to the academic atmosphere” or “persons in disrepute in the area from whence they came” or “those charged with crimes or moral wrongs.”

The policy barred Henry from speaking at UM in 1967 because he had been convicted of “disturbing the peace” in Bolivar County. The NAACP would continue “disturbing the peace” for years to come, later introducing the earliest bills to change Mississippi’s then-Confederate-themed state flag as a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives in the 1980s.

Roberts’ policy also barred civil-rights activists Martin Luther King Jr. and Charles Evers, the brother of slain voting-rights activist Medgar Evers. In 1969, the MSU Young College Democrats sued IHL in federal court, angry that they could not invite Charles Evers to speak to their group on campus.

Judge J.P. Coleman, a former Mississippi governor, ruled that the IHL speaker ban was unconstitutionally vague and could “never be enforced.” The court, though, allowed IHL 60 days to write a more specific list.

Roberts produced that list. The new regulation banned speakers who “might incite riots” or “whose presence might cause a riot,” former USM political science professor Monte Pilawsky wrote in his 1982 book, “Exit 13: Oppression and Racism in Academia.”

“Unlike the old speaker ban policy which was very unclear and very illegal, the board’s new one was very clear and very illegal,” Pilawsky wrote.

M.M. Roberts: ‘I Am a Racist … It’s Me’

Roberts’ skills as an attorney proved unhelpful when he returned to court in December 1969 to defend the revised ban, as he claimed that Evers’ speech could “do violence to the attitude of the fathers and mothers who send their children to school.” As a last resort, the IHL president told the court that Evers’ speech was on the same day as his own birthday and “that if Evers were allowed to speak, he, Roberts, would not have a happy birthday,” Pilawsky wrote.

The court quickly ruled Roberts’ policy unconstitutional again. That same month, he drew fire from USM students over remarks he made at an American Association of University Professors meeting at the Hattiesburg campus. During the speech, he talked about his more than nine years on the IHL board.

“The first real task I had for myself was to try to decide what to do with (James) Meredith going to the University of Mississippi, and I said, ‘No, he won’t go.’ I felt like he would go over my dead body,” Roberts said. “But as I’ve gone along through the years and looked back, I’ve said to myself really that I am a racist. Everytime I read a definition, I say, ‘Well, that’s me.’ I have no apology for it, though. It’s me.”

The IHL head then exhorted the professors gathered before him not to push for USM to hire large numbers of full-time Black faculty. There was no chance of it happening, he said.

“I think if you want to be a stupid idiot, just stir for that kind of thing,” Roberts said. “That’s a thing that’s destructive, and no one who thinks it seriously in his heart ought to get out of here and get out of this institution, because you don’t belong in our society if you think that is necessary—a thing we’ve got to do.”

The speech, which drew national attention, sparked a backlash among residents and college students and officials across the state.

United Press International reported that the segregationist Citizens Council, which then Delta Democrat-Times Editor Hodding Carter Jr. dubbed “The Uptown Klan,” defended Roberts as “a staunch defender of law and order.” The segregationist former governor who had appointed him, Ross Barnett, said that “conservatives in Mississippi and throughout the nation” were “proud” of his “unyielding stand” against civil-rights speakers on campus, UPI reported.

But the speech drew a rebuke from the USM Progressive Student Association, which days later passed a resolution, offering “that Dr. Roberts, not being in agreement with the majority sentiments in the United States, accept our offer of two hundred eighty one dollars and one cent to help purchase him a one-way airplane ticket to the Union of South Africa.”

Segregation was official state policy then in apartheid South Africa. But Roberts was not done, and did not take the students up on their offer.

A day after Charles Evers—who died July 22, 2020—spoke to the MSU Young Democrats in Starkville in March 1970, the IHL president wrote a letter to his fellow trustees expressing his “feelings of despair.” He concluded with a brazenly racist remark about Evers’ planned luncheon with the MSU Young Democrats.

“I know they enjoyed it. I hope he smelled like Negroes usually do,” Roberts wrote.

Despite his blatant racism, Roberts remained on the IHL board until his stint expired in 1972, though he stayed on as its attorney.

In 1975, then-USM President William McCain, who was also a segregationist and a member of the Citizens Council, dedicated the school’s new $6-million stadium in Roberts’ honor, praising the Jackson County native for helping fund the school during his time at IHL.

‘Things That Make America Great’

USM built the M.M. Roberts stadium around Faulkner Field, which the school first opened in 1932, dedicating it in honor of local businessman Louis Edward Faulkner (no relation to author William Faulkner). In 1948, the university’s president, R.C. Cook, called Faulkner “a great American interested in the things that make America great.”

Those interests included the fight to preserve racial segregation.

“Faulkner, a native Pennsylvanian and longtime Republican, was not a typical homegrown white Southern segregationist. But since arriving in Mississippi in 1905, he had become an ardent defender of Southern Jim Crow,” historian William Sturkey wrote in his 2012 dissertation, “The Heritage of the Hub City.” He also wrote about the businessman in his 2019 book, “Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White.”

Faulkner, who owned Faulkner Concrete and served as the president of the Mississippi Central Railroad Company, frequently wrote op-eds and gave speeches, warning about the encroachment of “socialism” and “communism”—which were and are commonly used as euphemisms for integration and racial equality. A Presbyterian deacon, Faulkner used his church position to argue against integrationist beliefs, and condemned Christian organizations that supported integration.

Publicly, Faulkner opposed President Harry Truman’s executive order establishing the Fair Employment Practices Committee, which barred companies from receiving federal defense contracts if they had segregationist hiring practices. The Republican businessman, who had arrived in Mississippi in 1905 at age 20, was selective about his opposition to the FEPC, though, Sturkey noted.

“Faulkner’s own company, Faulkner Concrete, and his employer, the Mississippi Central Railroad, had both received federal contracts during the New Deal and World War II; he had no real grievance over federal spending or influence when it benefited him. The source of his agitation lay in the suggestion that white Southerners should be required to share the spoils of federal money with African Americans,” the historian wrote.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that public-school segregation was unconstitutional in 1954, Faulkner joined the newly organized Citizens Council. In 1955, while the Citizens Council was seeking approval for tax-exempt status under the auspices of an informational and educational organization, Faulkner wrote to state and national leaders in an effort to get the NAACP’s own tax-exempt status revoked.

“May I ask, please, why the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., should be allowed to carry on their vicious and cruel attacks upon the good white and colored people of the South at the expense of taxpayers of this country on account of contributions to this organization’s being deductible from federal income tax?” Faulkner wrote in a letter to IRS Tax Rulings Division Director H.T. Schwartz that year.

The Republican businessman drew praise from prominent Dixiecrats, including segregationist U.S. Sen. James Eastland, who cited his “fine work,” and Brookhaven Judge Tom P. Brady, a Yale graduate who called Faulkner “a voice crying in the wilderness.” In 1965, Time Magazine described Brady as “the philosopher of Mississippi’s racist white Citizens Councils,” as he traveled coast to coast to give speeches and help establish Council chapters far from the South. With approval from some of the state’s top segregationists, Faulkner continued fighting against integration until his death in the early 1960s.

“The encouraged old Hattiesburger kept punching away at his typewriter, fighting another lost cause as he spent his final few days on earth desperately trying to block Mississippi opportunities from Blacks,” Sturkey wrote in his 2012 dissertation.

Like the stadium, the field where Black USM football players play today retains its original segregationist namesake. In 2003, though, the school did append the name, making it the Carlisle-Faulkner Field, to include another donor: Gene Carlisle, the wealthy founder of the Memphis-based Carlisle Corporation and a 1964 alumnus. Carlisle died in 2015, and is the only one of the three men that the stadium and field are named for who did not leave behind a segregationist legacy.

‘Dixie Darlings’ May Get New Name

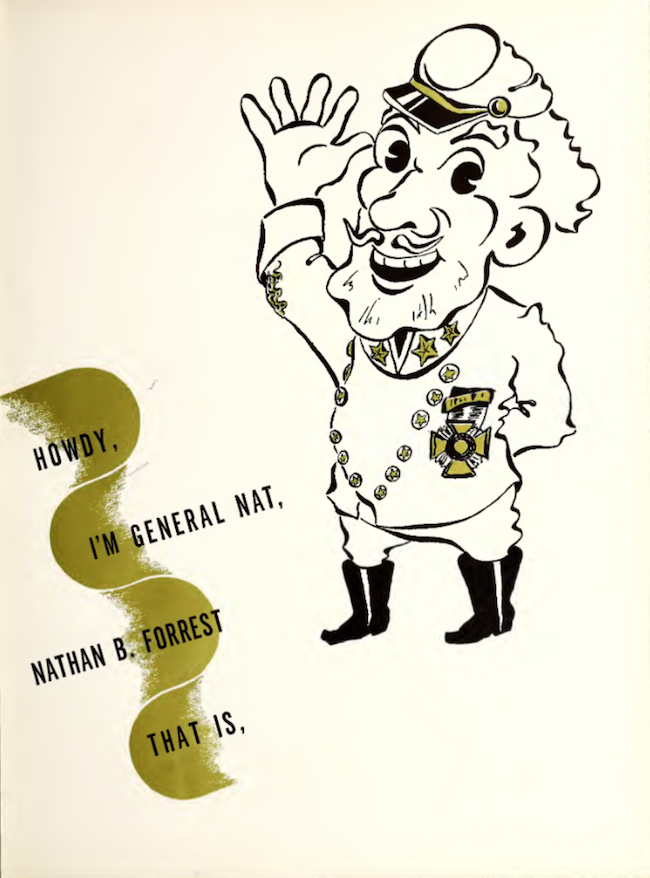

Though USM has not indicated plans to rename its stadium or football field, the university has slowly removed Confederate symbolism from campus since the 1970s. In 1972, the university retired its mascot, “General Nat,” and adopted the new Golden Eagles mascot.

General Nat referred to Nathan Bedford Forrest, Forrest County’s namesake—a Confederate general who helped found the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War and lead the organization as its first grand wizard, and is also known for attacks on Black U.S. soldiers in the what is documented as the Fort Pillow massacre in Tennessee on April 12, 1864.

In 2015, almost five years before the Mississippi Legislature voted to retire the Confederate-themed state flag this summer, USM President Rodney Bennett ordered the school to stop flying the Confederate flag on the front of campus.

On Aug. 13, Bennett, who is the university’s first Black president, announced in an open letter that he has ordered “a process to evaluate a potential name and music change.”

“I have tremendous respect for the Dixie Darlings organization and the ways in which it has represented The University of Southern Mississippi for many years. I remain confident that we will continue to accomplish our institutional goals together,” Bennett wrote.

As the name of the unofficial theme song of the Confederate army, use of the word “Dixie” has grown increasingly fraught in recent years. In Oxford, the University of Mississippi’s marching band in Oxford traditionally played Dixie at football games for decades, only retiring it in the past few years. Amid nationwide anti-racist protests this summer, country trio The Dixie Chicks changed their name to “The Chicks.”

At Southern Miss, the Dixie Darlings still enter the football stadium while the band plays the 1958 song, “Are You From Dixie?” Bennett said the school is now considering ceasing the use of that song.

‘It Could Be Me One Day’

This summer is far from the first time Southern Miss students have protested for change in recent years. After Bennett ordered the state flag’s removal in 2015, a pro-state flag group called the Delta Flaggers began protesting at USM’s entrance every Sunday. But after a mob of white supremacists went on a deadly rampage in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, student protesters spontaneously showed up the next day, holding a large “Black Lives Matter” banner in front of the flag group’s giant 1894 state flag.

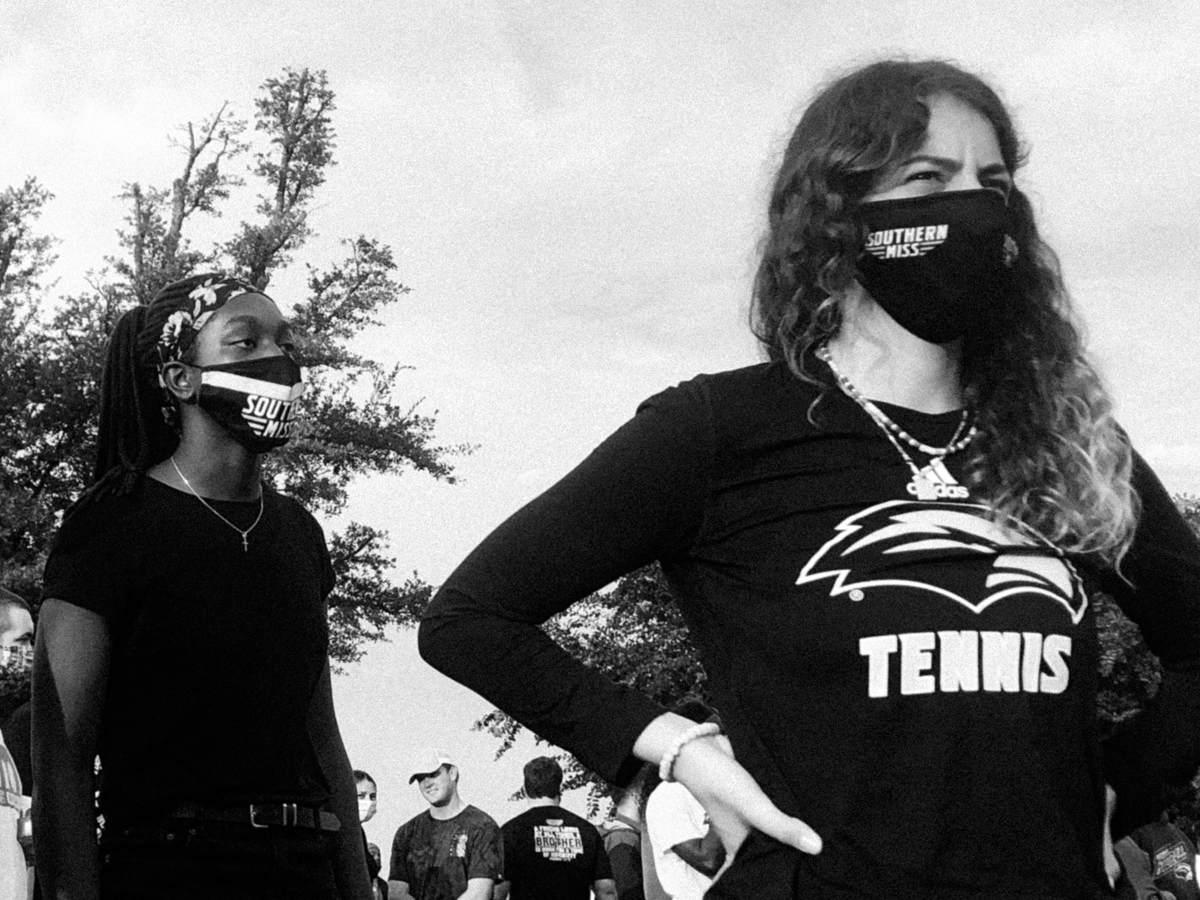

At the most recent demonstration at the campus entrance on Friday evening, Southern Miss athletes from other sports teams joined the football players.

Arina Amaning, a Black student from France who is on the Golden Eagles’ Women’s Tennis team, told the Mississippi Free Press that she wanted to support the football players’ walkout “because it could be me one day.”

“In France, these things happen—discrimination and police brutality happen in France. It’s maybe less, but it’s still there, and over the summer, a lot of protests and marches happened there,” she said. “Because we also have a lot of Black people and a lot of races, and there is a lot of discrimination against Black people there.”

Amaning said France’s racism may seem less virulent than U.S. racism may partly because “people don’t talk about it” as much there. But systemic racism is still an issue, she said, not only in policing but in other areas ike employment.

Her teammate, Ebru Yazgan, is from Turkey, a 98% Muslim nation.

“Coming to America, we don’t have many Black people in Turkey, so it was a really different environment and racism was on a different level,” Yazgan said. “I’ve known Islamophobia existed, but coming here, I realize how Black people are treated. I can say I’m not religious, and I can get away with it.”

The Golden Eagles tennis player said she has been using social-media platforms like Instagram to talk to her friends and family about racism—especially those back home in Turkey who “don’t know about it.” Yazgan said she has also tried to participate in “any march or protest as much as I can.”

“And my teammate is here, so I just made sure I was here with her and supporting her so that she knows I’m with her,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled USM football player Swayze Bozeman’s last name as “Boseman.” We apologize for this error.