OXFORD, Miss.—”Ole Miss has never really been integrated.”

Dr. Charles K. Ross saw this audacious claim laid out in a Mississippi Free Press investigation of controversial plans to renovate his campus’ Confederate cemetery earlier this summer. A teenaged Don Barrett said those words to a New York Times Magazine writer on the University of Mississippi campus in 1963, the year after James Meredith became the first Black student to enroll at UM, despite violent opposition. Those words stuck with the professor.

“That’s powerful,” Dr. Ross, a UM history professor and director of the African American Studies Program, thought when he read the piece in July.

“He’s absolutely right,” Ross told the Mississippi Free Press earlier this week, just days after the MFP published a three-part series on racist emails and responses between a wealthy donor and the former journalism dean. Or, at least that’s what many actions and symbols communicate to Black faculty and students who want UM to fully embrace and communicate solutions.

“African Americans cannot put their arms around this whole concept of ‘Ole Miss,’ and what it means in this history. … You can put your arms around, potentially, ‘The University of Mississippi,’ and it’s got a lot of work to do to even get that done. But this whole idea of embracing and feeling as though you are a part of ‘Ole Miss’? No,” Ross said of the Black experience at UM.

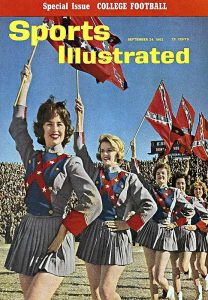

The nickname “Ole Miss” is everywhere you look on the Oxford, Miss., campus, from football helmets to official university vehicles. Its origin is traced back to the establishment of a yearbook for the university in 1896 by members of Theta Nu Epsilon, a chapter of Skull and Bones then on campus. The Mississippian, as the campus newspaper was initially called, reported on May 13, 1939, that Elma Meek, a member of the committee tasked with creating a yearbook title, was the person behind the name.

Elma Meek told the Mississippian then: “I had often heard old ‘darkies’ on Southern plantations address the lady in the ‘big house’ as ‘Ole Miss.’ … The name appealed to me, so I suggested it to the committee and they adopted it. I have never thought much about the matter, for I never dreamed, of course, that the term would grow into such popularity and favor.”

“The term ‘Ole Miss,’ has got to go,” Ross, a graduate of Stillman College and Ohio State University, said. “It must be totally removed in its connection to the university. Any kind of apparel. It is not a nickname befitting where we are in the United States of America on race relations as we sit in 2020.”

Dr. Ross is not alone in pointing out the “Ole Miss” moniker problem; it’s well-known in the higher-education world. “The university’s leaders know the nickname is a problem. Their own consultants told them that years ago,” The Chronicle of Higher Education reported late last year.

“They’re also keen to promote a more inclusive environment at an institution that remains plagued by racist episodes,” the Chronicle continued. “But they face pressure from wealthy alumni who oppose changing symbols, as well as from within a campus Greek system that is also perceived as wedded to Old South traditions. The university has responded by acting like the problem doesn’t exist.”

Dr. Ross has been talking about the necessity for systemic and equitable change since he arrived in 1995—to a campus with buildings built by slaves and still named for slave owners. He found a perpetual struggle between those clinging to the past and others wanting to modernize the DNA of the university from the one that young Barrett, already a cross-burner by 1963, had embraced to one where Black students can “love this campus just as much as everyone else,” as Associated Student Body President Joshua Mannery and Black Student Union President Nicholas Crasta wrote in an MFP Voices column this week.

That can be hard with revelations about racist actions and words by some in the UM community. Additionally, Black campus leaders say, a standard university response can seem more like climbing into a bunker than an honest reckoning and transparent embrace of solutions.

“If the incident is large enough to warrant a public response, the university typically tends to acknowledge what happened and reaffirm the values that we all live by, noticeably lacking any next steps or actual substance,” Mannery and Crasta wrote this week in the Mississippi Free Press. “Often, that acknowledgement feels accompanied by a noticeable use of generalization.”

Worse, the Black students say, the university does not publicly detail its plan to repair the damage while talking enough about the positive actions already underway to tackle systemic issues, whether involving students, faculty or fundraising. “Additionally, the university does not spotlight measures that are taken to improve the student experience, leaving students and the UM community without awareness of important work that is being done,” Mannery and Crasta wrote.

To their point, the public university has declined multiple interview requests to respond to the recent email and fundraising revelations or to talk about existing or new solutions they are pursuing.

To Ross, UM’s ubiquitous nickname symbolizes this calcification—and the deference some powerful people still expect Black students and faculty to show to the “Ole Miss” of the past.

“We understand very clearly the history behind this term, where this term originated from. That it is a term that, of course, individuals that were slaves had to use in a very deferential manner to refer to the plantation master’s wife or even daughter as ‘Ole Missy,’” Ross said. “So this is a clear vestige of slavery that is used particularly in athletics when you have it scripted on helmets, in which your key players—individuals that really decide the outcome of a football game—are African American. And you want them to wear this on their helmets, OK, and we’ve got to continue to refer to this school in that way.”

Like other old customs that keep a potentially modern university mired to a despicable past, Ross describes, the nickname is like a stubborn albatross. “And so, that must go,” he insisted, “and that’s going to be probably the thing that will be most contentious. You will have a tremendous amount of individuals that will make some serious threats. People will probably make vows never to give contributions.

“People will just feel like, ‘That is the last straw. That’s the last shot of the Civil War.’”

‘We’re an Institution First and Not a Business’

Dr. Ross believes real, enduring and truly integrated change can come to the University of Mississippi, however. It just won’t be easy and painless, and it will require uncomfortable reckonings and deep listening to people of color in the UM community, especially Black Mississippians.

“What will have to happen,” Ross told the Mississippi Free Press this week, “is that pressure will have to be applied at the grassroots level to push back on the board and many very conservative white alumni that don’t want the university to move forward.”

The “board” is the powerful Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning, which recently caused a campus outcry when it bypassed its own hiring process and appointed former IHL commissioner Glenn Boyce as the UM chancellor after Jeffrey Vitter’s tenure ended.

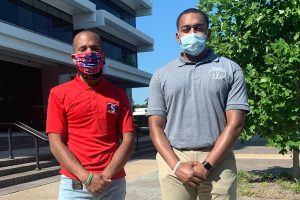

One group doing that grassroots work is the University of Mississippi Black Caucus. Following in the footsteps of James Meredith in 1962 and other southern civil rights leaders, this vibrant group of young scholars is taking action against racism and inequality at their university and beyond.

The UMBC is young, having formed just weeks ago in reaction to the lack of minority representation at UM, where only 12% of its student body is Black. “Thinking about (a) Black Caucus, at the beginning of the summer, it was just a conversation,” UMBC Vice President and founding member DeArrius Rhymes of Hazlehurst said.

The group, led by presidents of several Black organizations on the UM campus, has come a long way fast since those initial conversations about bringing more Black students to the Associated Student Body, a strategy they saw as necessary to creating an organization that could fulfill the group’s solution-driven goals.

UMBC began to organize Black associations on the UM campus, officially establishing themselves on July 1, 2020, in part due to transparency issues raised by the IHL’s approval of the Confederate monument relocation and cemetery renovation plan. Students say the chancellor had not conferred with students or faculty involved with calling for the statue to be moved to the cemetery about a little-known plan to add headstones, lighting and other features, a strategy university alumnus and donor Don Barrett had backed, and other donors and statue critics had opposed. The surprise cemetery plan and renderings that suddenly emerged on June 19 at the IHL meeting approving the statue’s move convinced founding Caucus members that they would need to rally a coalition of allies in order to obtain a seat at the university’s table and install real change at the institution.

Like many who attend the University of Mississippi, UMBC’s ties to the school are generational. Black students also follow their families to the university, often instilled with a sense of purpose to help the school become fully inclusive and equitable. “(UM) has definitely made a lot of progress since James Meredith came,” UMBC Treasurer Tim Herrington of Grenada said in an MFP interview via Zoom this week with several of the caucus members. “My dad was here 25 years ago. We’re trying to get to a point where we’re an institution first and not a business.”

Herrington, like the ASB and Black Student Union presidents, expressed concern with what they see as the university’s tendency to place the dollar before the dignity of all students. This is illustrated by what they see as the coddling of wealthy donors like Blake Tartt III, who openly talked about wanting UM to return to the university he remembers, and Don Barrett, who told the MFP that his Christian faith had reversed the racism of his youth. Still, his closely guarded plan that the campus’ largely ignored Confederate cemetery be renovated into more of a tourist destination drew the wrath of many students and faculty members this summer, helping solidify the Black Caucus’ mission.

“That’s the underlying racism we’re talking about,” UMBC Vice President Rhymes said about the university putting donor desires above the involvement and concerns of Black students. “They need to start being proactive instead of just active.”

“We can’t wait until it gets in the news,” Herrington added about controversial revelations.

‘How Hard Are You Willing to Try?’

Now, the Black Caucus is united in the belief that the University of Mississippi needs to squarely face its history and figure out how to finally and fully move past it.

“My point is,” UMBC Historian and Stamps Scholar Tyler Yarbrough of Clarksdale says, “I think the university needs to yield to its history. Stop and look directly in its face.”

While UM administrators are asked to reckon with the hateful symbols on campus and racist throwbacks attempting to prolong the university’s reputation as a Confederate Mecca—some of whom donate big bucks or at least promise to—the Black Caucus and others are working to build up the communities they hail from.

Herrington and Rhymes have been busy raising scholarship money for students living in underrepresented areas of Mississippi so they can attend UM, too. Even in the face of the racist comments and actions that bubble up on campus—or off-campus at the hands of UM students—and what they see as inadequate official responses and solutions, UMBC President Amirah Lockhart of Mendenhall said that she, like all members of the Black Caucus, loves the University of Mississippi and wants to be part of its evolution.

When asked in what ways she benefitted from choosing UM, Lockhart recalled a trip she took to Washington, D.C., funded by UM. “It’s something I want for everyone,” Lockhart said of the opportunity.

It’s not like other UM donors do not support Black students and a new kind of future for the university—many back such opportunities and push back on funders who want to maintain the old “Ole Miss” and its symbols. Former Netscape chairman and Mississippi native Jim Barksdale, a major UM donor, told the Mississippi Free Press he backed out from raising funds for the Confederate cemetery enhancements after learning the specific details of the plan. Soon afterward, the chancellor scrapped the plan for headstones in the cemetery.

Caucus members are bursting with ideas that UM administrators could pursue to make the university a place of full inclusivity—if leadership would listen and respond loudly and with courage. The students want to see what just about everyone associated with UM calls “Mississippi’s flagship university” become a place that truly represents the people of Mississippi, nearly 40 percent of whom are Black. When the university opened in 1848, the state was majority African American, in fact, with enslaved people outnumbering white residents.

A major concern the Caucus shared is Black representation and enrollment at UM, which is currently hovering around 12 percent, the lowest of all public universities in Mississippi, aside from the historically Black institutions. Caucus members find this paltry percentage to be unacceptable for the state with the largest proportion of Black people in the nation.

UMBC President Lockhart hopes to see UM triple down on recruitment efforts that would bring more Black students to the university.

That could start with recent UM graduate and its first Black woman Rhodes Scholar Arielle Hudson’s call for more in-state scholarships for Black students to increase their proportion of the UM student body. Likewise, she wrote in the Mississippi Free Press this week, the administration must “filter out” openly racist targets from the UM donor list, leaving the ones willing to fund a fully diverse, equitable and inclusive university.

Is ‘New Miss’ Within Reach?

You might have seen James Meredith, the first Black student at UM who has a statue but not a building named for him there, sporting a ballcap with “New Miss” inscribed on it.

It stands to reason that “New Miss” is now only an idea, an aspiration, something still in the process of being built. But what exactly is it? What would it look like? A campus devoid of Confederate symbology? No more buildings named for slave owners and white supremacists? A university with Black enrollment numbers well above 12 percent? A secure place for all people of color where all know and accept that hate has no refuge? A place where the university administration addresses racism head-on and publicly? A flagship university no longer referred to as the plantation mistress? A campus that Black students can love as much as anyone else there?

Black Caucus members say “New Miss” should be all of those things. Really, though, it all begins with representation. “When we talk about this need to increase scholarships and making sure everyone can afford to get this knowledge,” Tyler Yarbrough began, “we understand that knowledge is needed to help improve our communities, and that’s something serious. That is so serious.” The emphasis was his.

Amirah Lockhart spoke about the importance of events like the MOST Conference, an educational recruitment gathering for rising African American seniors in Mississippi organized by the Center for Inclusion and Cross Cultural Engagement. At MOST, students and their families learn about admissions and financial-aid processes, as well as the campus resources available at UM. Prospective students also listen to the testimony of successful UM students and can explore their future career options.

“I would really love to see the MOST Conference expand or even have several similar programs that are just made to increase Black representation at (UM),” Lockhart said.

The UMBC members collectively stated that UM, although progressing, still has a lot of work to do in order to reach students in underrepresented areas of the state. Tyler Yarbrough, who speaks fondly of his Delta origins, believes UM needs to further invest in minority students who call Mississippi home. The Black Caucus is adamant that proper representation will pay off in a way that the University of Mississippi may not currently be able to imagine.

Yarbrough, the Stamps Scholar, said the University of Mississippi acted as “a gatekeeper to knowledge in a society until James Meredith forced it to integrate.” That knowledge, and the network and opportunities and nurturing that come with it, must intentionally be opened up to all young people in Mississippi, these leaders believe.

The Clarksdale native will be the first to tell you exactly how beneficial a generous scholarship has been to his own life. Yarbrough wants the same experience for others. “If more minority students, more people from the Delta got it, if more folks from Jackson got it, what would that mean for people?” he asked.

Yarbrough believes UM is a cornerstone for lifting up all of the state if it fully embraces and telegraphs its role as a public institution that is transparent and respectful to everyone—far beyond the environs of its campus or the sometimes-limited vision of some of its donors, alumni and administration.

“The university has to understand its role in bringing about this new future for Mississippi,” he told the Mississippi Free Press.

Whose Culture Is It, Anyway?

In emails to the former UM School of Journalism and New Media Dean Will Norton, 1984 UM graduate Blake Tartt III relayed the type of sentiments that anchor UM to the past. “All may think I am living in the past and not progressive enough,” he told the journalism dean, amid a batch of racially disparaging emails about Black students and “culture.”

“I happen to know what happens when a place is overtaken by the wrong elements,” Tartt wrote. “For all the movement for total inclusion social engineering does not work.”

Ashton Pittman reported in the Mississippi Free Press on Aug. 2 that Tartt grew up in Houston, Texas, in the now “majority-minority” Harris County, where a majority-white population had dominated a decade earlier.

“Blake, I have been really disappointed for a long time with the way this culture is going,” the UM journalism dean responded to that email to his potential donor.

Within days of the MFP series publishing, Provost Noel Wilkin called the emails the investigation revealed “appalling.” But he stopped short of speaking to how the university would address systemic issues the emails revealed, even as he expressed that studies found that fundraising is more effective, drawing more dollars, when such donor proclivities are not coddled, as Arielle Hudson called it in her later column. Wilkin declined an interview to detail specific solutions the university is engaging, telling the Mississippi Free Press that UM was not ready to talk about plans to “outside groups.”

NEW: University of Mississippi Provost Noel Wilkin responds to our @MSFreePress UM emails investigation, saying he "condemns" the "appalling" actions described. "They're not reflective of who we are as a community…We're not the same institution we were in the past." #UMEmails https://t.co/7dc3J5bwLi pic.twitter.com/csAaTquijy

— Ashton Pittman (@ashtonpittman) August 7, 2020

That kind of response befuddles Black students who want the public university to clearly state its plans and be more forthcoming about the problems and the solutions it will engage without expecting them to do the heavy lifting of healing racism and of modeling how far the university has come on race. Student leaders Mannery and Crasta called such vague UM responses part of “the repetitive cycle of crisis management from the institution, especially in regard to race-related issues.”

“This approach has, for so many students, felt like an intentional effort to minimize any damage to the UM brand rather than assuage the distress of those affected,” the men said in the solutions-driven MFP Voices piece they asked to write after the UM emails series came out.

Attempts to minimize race-related problems rather than talk loudly and publicly about anti-racism solutions, means those messages don’t reverberate to potential students around the state who could help increase the 12% enrollment if they better knew the efforts under way and heard more from administration and alumni actively leading efforts to extricate the institution from racist belief systems of the past.

Black student leaders say there must be cultural shifts at the university, but not the slide backward that some white alums, such as in emails the MFP series quoted, would prefer. Instead, it must be a fully inclusive, welcoming culture that protects students first.

“That culture shift begins with our UM community from the top-down serving as better allies to not only Black campus stakeholders, but to our Asian-American, Hispanic, LGBTQ+, International and other communities all across the board as well,” Mannery and Crasta wrote.

In the MFP interview, Black Caucus members reinforced that the “diversity, equity and inclusion,” also called DEI, approach must apply to faculty as well. “We talk about the need to diversify staff. Diversify staff! Diversify staff!” Yarbrough exclaimed. “We understand that people like us have so much to offer to the white kids that have grown up in the suburbs. Who have grown up in Ridgeland and on the Coast, who haven’t had to worry about anything or engage with any cracks in our society.”

Interim Journalism Dean Deborah Wenger released a statement this week after the MFP’s UM emails series that shows the current inadequacy of UM’s staff “diversity” problem in a state that is 38% African American. Wenger wrote that the journalism school has made progress on faculty diversity: “six of the school’s 32 permanent full-time faculty members are Black,” she wrote, adding that they are reworking the diversity plan in place there since 2011.

In response to the MFP discoveries about fundraising emails in her school, Wenger added that the department is revisiting ethics for communications with potential funders: “we are developing a ‘Statement of Principles for Fundraising’ that will guide our school as we work with donors going forward,” Wenger wrote.

The Mississippi Free Press also spoke with Texas poet, educator and UM PhD candidate Joshua Nguyen about the importance of increasing inclusion and representation in faculty and leadership roles at the University of Mississippi.

“There’s more of a camaraderie,” Nguyen said of typical relationships among students and educators of color. “There’s a quiet understanding. We understand each other, and we’re navigating this very white space together, and that can be comforting to some people.”

Nguyen said it is crucial for students of color to have mentors, role models and educators who look like them and with shared experiences. “Just to know that someone else is navigating this space, so I think I might be able to do the same thing,” he explained.

‘Give Them Their Greatest Fear’

In the aftermath of the Meek controversy after the UM-Alabama football game in September 2018, Dr. Charles K. Ross and Poet Joshua Nguyen joined a list of UM academics who authored and signed a letter published in the Daily Mississippian demanding “reparative justice” at the university. The letter listed specific actions needed to mitigate the harm caused by Meek’s racist Facebook posts using the photos of Black students partying alongside white ones on the Oxford Square, in which he warned fellow Oxonians that the “values we hold dear that have made Oxford and Ole Miss known nationally” were in danger.

The reparative-justice letter addressed the issue of Meek being the namesake of the journalism school, as well as other racist symbols on the campus, and denounced ongoing affection for the institutional racism that Confederate symbols represent.

“Meek’s comments expressed nostalgia for institutional racism and policies of racial exclusion, both of which are represented by the buildings and monuments on our campus,” the letter stated.

The call for reparative justice pointed out that students are clear about the effects of such symbols on their lives and campus experiences. “In the listening session on Sept. 20 (2018), students emphasized how monuments and buildings named after slave owners and segregationists act as a constant reminder of exclusion and source of harm,” the signers wrote. “Removing Ed Meek’s name from the School is a necessary, but basic, step in a much longer process of reparative justice. Our university must firmly stand for its stated values of intellectual excellence, non-discrimination, and inclusion and support for all its students.”

Meek’s name was indeed removed from the j-school in a very public fashion, but the journalism dean, some faculty members and journalists knew the likely identity of the man who took and distributed the photos to Meek, Norton and others, but it was not revealed publicly until the MFP’s Aug. 2, 2020, investigative series.

Ross, Nguyen and UMBC members all discussed this week how cutting ties with racist donors and alumni, whose words and deeds can negate and set back anti-racist progress, would be an important step in bringing forth reparative justice now to help heal a pattern of racist incidents, and perhaps stop them from recurring.

“The best thing to do (with racist alumni) is to give them their greatest fear—to in essence say, ‘You can no longer be associated with the University of Mississippi,” Dr. Ross told the Mississippi Free Press. “You can’t donate money, you can’t buy football tickets, you can’t buy tickets to go to the Ford Center.’ Whatever the case may be. If you did that, I think that then you would begin to send a message to many individuals that are in those circles.”

That public rejection of racism impersonating school spirit and pride would send welcoming messages to students and faculty and allow alumni and donors who embrace diversity, equity and inclusion to take center stage and publicly project the right and consistent message about what UM strives to be, Ross described.

“If we strip away all these things, we have an opportunity to now truly become a public institution for the first time in our history,” Ross continued. “We have an opportunity now to build something that has a whole unique identity and perspective. And who knows? Maybe there’s a whole other group of donors out there that you could begin to reach out to.”

Ross had a message for young leaders who want to see their university fully integrated, equitable and inclusive. “Stay the course,” he advised.

“They have been very brilliant in their use of social media,” Ross said of Black UM students and leaders. “They have used it as a communication strategy to rally a diversity of people. I am extremely proud, particularly of the African American student athletes that have been involved in several protests since the death of George Floyd.”

Ross is inspired to see younger generations step up and claim their power. “This is a very, very powerful group of individuals,” he said. “The more they recognize how much power and leverage they have, the more that they can potentially do to effect change. More so than maybe any group of people on our campus.”

Learning and Hope from a Timeline of Gradualism

As might be expected from an African American Studies professor, Dr. Ross drew on the lessons of history at the university long called the nickname of the plantation mistress. In so doing, he intentionally or not summarized UM’s gradualism of giving up its Confederate iconography and easing out of its embedded beliefs in fits and starts over decades.

“Every time UM has made a stride, or has done something to try to distance itself from its racist founding, it has become stronger,” Ross said. “UM became stronger after James Meredith integrated it even though two people died, and you had a riot that went across our university and Oxford. The university got stronger.”

“The university got stronger in 1982 when (Black cheerleader) John Hawkins said ‘I’m not going to carry the Confederate flag.’ The university got stronger in 1997 when Robert Khayat said, ‘Look, you can’t bring the flag into the stadium.” The university got stronger. Enrollment went up.’”

“The university did not lose strides when it got rid of Colonel Rebel, stopped playing Dixie,” Ross continued, essentially preaching the anti-racism gospel of seeking strength and growth within equity and inclusion.

“The university continues to move forward when it distances itself from its racist baggage.”

Or, as student leaders Josh Mannery and Nicholas Crasta wrote in their column this week, calling the UM university community to action, “It’s time we finally made good on the work started in 1962.”

_________

Editor’s Note: In the reporting of the UM emails series and follow-up reports, the MFP did not confer with members of either of our boards or any donors associated with the University of Mississippi to avoid conflicts of interest.

Also see: From Racist Emails to ‘Witch Hunts’: A UM Emails Timeline

Watch: Reporter Ashton Pittman and Editor Donna Ladd discuss the series during the 2021 Ancil Payne Award for Ethics in Journalism ceremony (40:00) and read more about the award here.

Read the full UM Emails reporting series to date:

- ‘The Fabric Is Torn In Oxford’: UM Officials Decried Racism Publicly, Coddled It Privately

- ‘The Ole Miss We Know’: Wealthy Alums Fight To Keep UM’s Past Alive

- UM’s ‘Culture Of Secrecy’: Dean Quit As Emails Disparaging To Gay Alum, Black Students Emerged

- ‘Appalling’: UM Provost Decries ‘Hurtful’ Emails About Black Women, Gay Alum

- Ole Miss’ Coddle Culture: Ole Miss Will Stay ‘Ole Miss’ Without Radical Shift

- EDITOR’S NOTE: The Decisions, Process, Motives Behind Ashton Pittman’s Series On UM Emails

- Perpetuating Patterns: It’s Time To Build A Better University Of Mississippi

- After UM Emails, Dean Plans ‘Anti-Racist’ Training, Donor Changes to ‘Remake Our School’

- ‘Ole Miss’ Vs. ‘New Miss’: Black Students, Faculty On How To Reject Racism, Step Forward Together

- UM Closely Guards Climate Survey Providing Window Into Social Issues, Sexual Violence

- UM Probes Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails As Ex-Dean Keeps $18,000 Monthly Salary

- ‘Our Last Refuge’: UM Faculty ‘Terrified’ As Officials Target Ombuds In Bid To Unmask Whistleblowers

- ‘Like He Was Disappeared’: UM Faculty Fear Retaliation After Ombudsman Put On Leave

- UM Appoints Acting Ombuds As Weary Faculty See Effort To ‘Stamp Out’ Anti-Racism Voices

- UM Retaliating Against Ombudsman for Protecting Visitors’ Privacy, Org Says

- UM Accuses Ombudsman of ‘Raising False Alarms’ Over Whistleblower Investigation

- A Matter Of Trust: UM Controversy Shows How Ombuds Programs Should, Shouldn’t Function, Expert Argues

- UM Pursuing ‘Criminal Investigation’ Into Whistleblowers Who Exposed Racist Emails

- Ombuds ‘Exonerated’ As UM Emails Whistleblower Hunt Fails to Identify Sources

- Will Norton, Ex-Dean in ‘UM Emails’ Race Saga, Quietly Departs University