The concept of death is straightforward—you live; then you die. And when you die, your body decomposes, becoming nothing. Our bodies transform into a tool or vessel for recycling energy into the environment as heat and other chemical forms of energy. Scientifically romantic? Sure, why not. But also, is it anticlimactic? I mean, yeah.

Is death final? Just a void of nothingness? Is it a barbecue where Tupac comes up to you and yells, “Cousin?” Does death transport us to some supreme entity who is all good, all powerful and all knowing? Or is death something our complex, yet naive human brains cannot begin to envisage?

Barbecue. It’s definitely a barbecue, with Joe Torry fervently brushing his hair. (His poor hair follicles; they were fighting for their lives.)

“Poetic Justice” references aside, all of us have an idea—no, better yet, a hope—of what death represents. And if you’re wrong, well, good luck tweeting “my bad.” Apart from Herman Cain, tweeting from beyond the grave seems to be a rather difficult endeavor.

We. Don’t. Really. Know.

We just know, after a certain age, that we won’t live forever. It’s our personal wake-up call. And what do we do after our wake-up call? We tend to live the rest of our lives creating children, creating influence, creating words and legacies just to supplement our finite existence. Those practices and entities are birthed to help us die, meant to outlive us, giving us relief as we all inch closer and closer to the unknown.

‘I Assumed I Had Less Time With My Parents’

My father, Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore, was 44 when I was born. My mother, Anniece McLemore, was 38. I’ve never truly forgiven them for having me that late in their lives. As a kid, I assumed I had less time with my parents compared to others who were my age, especially being that my time was already split between them since I was 3 years old due to their divorce.

I lived with the fear of one of them falling asleep and waking up the next morning at the Sam Cooke concert. I feared they would leave me before I established my own entities to supplement my finite existence. And now, as an adult, I look around at my friends who have younger parents. Some of their parents are no longer with us. Mine are both still here. Both of my parents are healthy, relative to their age. Yet, I still haven’t forgiven them. I doubt I ever will. I deserve more time with them, even while they do everything within their power to create more time for us.

My father had a health scare a few months back. He was losing weight, and not on purpose. When an 83-year-old un-purposely loses weight, it usually means their body is desperately trying to combat a virulent or a mutation. Both he and I assumed the worst, while hoping for the best, or at least the status quo. We both share this pessimistic defense mechanism. I got it honest, and it sometimes makes for a miserable existence, even if it helps me better cope with inauspicious news. However, I’m still less pessimistic than my father. My mother made sure I would be less jaded. Thank Janet “Justice” Jackson for my mother and her balance.

His unexplained weight loss took us down the road of uncomfortable conversations. I believe we call it “next steps.” Jesus. Corporate lingo and death-around-the-corner lingo horribly converged. I didn’t want to be here so soon having this talk. Me being thrusted into a leadership role over someone who has led me for my entire existence.

“This ain’t fair,” I thought. I had the conversation, anyway. And for as much as I dreaded the “next steps” talk, it was relatively mundane. We discussed if he should move to Georgia to be closer to me, my wife and of course his two grandchildren. We discussed whether he should get one of those at-home caretakers to help with household chores and make sure he doesn’t break his hip doing a TikTok dance he saw on “the Facebook.” We talked about comfort. The conversation was light. But my mind was heavy. After making oral, half-assed agreements, we got off the phone.

I exhaled.

My wife slowly made her way over to me on the couch, where I was sitting. She asked if I was OK. “Yeah, I’m good now. Just gotta start thinking about next moves. And he told me it was getting harder and harder to walk up the stairs. So now it’s just …” I cut myself off and began to sob, uncontrollably. I wanted my father back. The one I knew. The one who could get up and run 5 miles at the local park. The one who protected me from this world’s harm while simultaneously warning me I would one day have to protect myself from those very same harms.

I wanted more time. I deserved more time. I demanded more time. I demanded more time so that he could see the fruits of his legacy in the form of his granddaughters. Because they deserve more time, too. What an absurd demand. But I didn’t care. I reverted to that little boy, upset at both of my parents for giving me life at an unconventional age. Never mind we assumed my father’s time on this earth was nearing its end. It was all about me. I tucked myself away, in my selfish corner, like a petulant child.

A week or two after the tears dried, the medical tests started to come back. Negative. Negative. Negative. The weight started to fill out his frame. Ice cream, peach cobbler, optimism and hope were winning. Thank you, Mom.

There was one last medical test my father had to take. I decided to travel to Mississippi to help him get through it. I brought a recorder with me that I purchased off Amazon one random post “next steps” night. I wanted to ask him questions. Ask him his biggest regrets. Ask him about his greatest accomplishments. Ask him about his legacy. I wanted to use yet another vessel that would outlive him, so I could re-share those intimate thoughts with myself and eventually my children. Because of distance and age, how much more time do we have left with each other? How many more times can he share his wisdom? How many more times can he share his legacy? I decided not to record my father’s thoughts that time. I thought it was bad timing.

And yet, I felt and still feel the urge to not let my father’s legacy go to waste.

The Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore Endowed Scholarship Fund

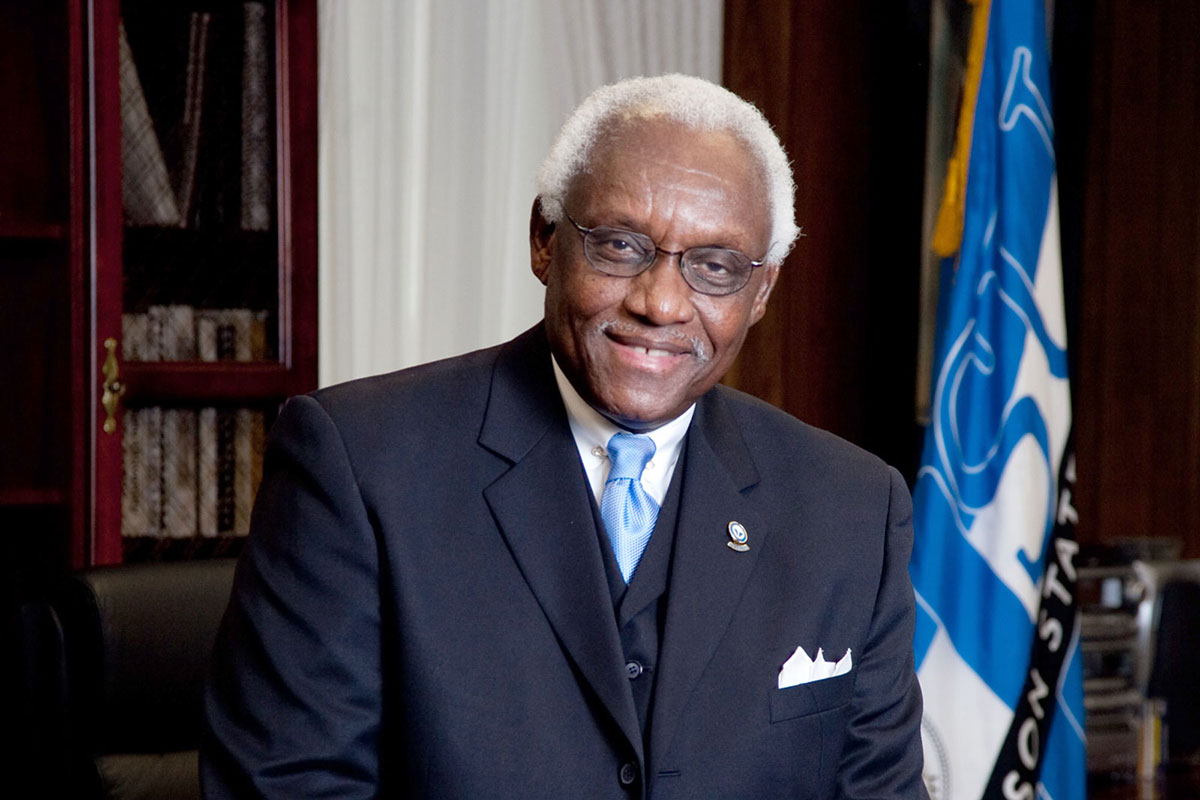

My father’s legacy is well documented. I’ve written about it. Others have written about it. There have been oral histories and documentaries and essays and papers created surrounding his work. That work includes risking life and blood to get Black Mississippians registered to vote during the height of Jim Crow terror; it includes serving as the inaugural president of the Rust College chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; it includes standing beside other Civil Rights titans such as Julian Bond, Frank Smith Jr., Ella Baker, Elanor Homes Norton, and of course, Fannie Lou Hamer; it includes traveling with Hamer to Atlantic City for the 1964 Democratic National Convention as one of the representatives of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the Mississippi Democratic Party’s right to participate on the grounds of the state’s segregated election process.

My father’s work also includes an entire post-Jim-Crow-era legacy in which Jackson State University represents as its foundation. At Jackson State, he became the founding chairman and professor at JSU’s political science department and served as dean of the university’s graduate school. Fighting for Black Mississippi equity and being a tenured professor at a storied HBCU garnered him plenty of attention. This attention had him hitting the speech circuit, something I became all too familiar with.

But even while the speeches were made, so was time. Time for me. Time for his legacy. From being a tenured professor, to giving speeches around the country, to founding and running the Hamer Institute, to Jackson, Miss., political offices to Interim President of Jackson State University—my father still made time for me. I’ve written about that, too. And I’m writing about it now because I’m forever grateful. And now he’s collecting legacies like infinity stones. He’s an alderman in Walls. He’s a grandfather to two amazing girls.

And then there is the Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore Endowed Scholarship fund.

Ironically, one of the more cardinal legacies my father yearns to leave behind is a legacy he didn’t start. His grandfather and my great grandfather, Leslie Williams, started the legacy of education in our family. And my father and his brother, Eugene McLemore, carried the torch Leslie Williams started, even though he only had a fourth-grade education. Having a scholarship fund established in his name was something my father was proud of.

You would think the prestige of political offices, accolades and lifetime-achievement awards would be what defined one’s legacy. No. For him, it’s education because that was his foundation. Education is what took him to heights no Walls, Miss., Black child should have reached, growing up picking cotton in the 1940s and ’50s Jim Crow. Contributing to this legacy and the legacy of other funds—such as the Dr. Jacquelyn C. Franklin Endowed Scholarship, the Isaiah Madison Endowed Scholarship Fund or the Catherine Coleman Fund—takes other Black children to heights above the predisposed station created and reared by white supremacy and generational trauma.

Education. What a simple, yet paramount legacy, a legacy I honestly took for granted before the “next steps” conversation was had with my father—only because I’m lucky enough to be born into a family legacy where education is a right, not a privilege. For that I apologize. Scholarship funds, like the Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore Endowed Scholarship fund, ensures more students benefit from the world-class education at Jackson State University, so I’m asking you to donate whatever you can to help this fund reach its $50,000 goal.

As for death? Hell, I don’t know, nor do I pretend to know. It’s maybe nothing, and yet for whatever reason, I hope it’s something. Even if it’s probably, well, maybe nothing. No matter. Because it’s not only about how you live, but what you leave behind. The legacies we leave behind—good, bad, or indifferent—affect not only us, but more importantly, others. That’s what the true meaning of legacy represents.

As for my legacy? That’s easy. Showing up to random, Black ass cookouts like I’m a third cousin, twice removed.

If you would like to donate to the Dr. Leslie Burl McLemore Endowed Scholarship fund, click here. To donate via check, mail it to Jackson State University Development Foundation, P.O. Box 17144, Jackson, MS 39217. To donate over the phone using a credit card, call 601-979-1760 and say you would like to give to the McLemore Fund.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.