Growing up in Hernando, Miss., in the 1950s, a young Leslie-Burl McLemore would often forgo heading to the playground with other students during his lunch breaks at McKay Elementary School and instead enter the school library, searching the shelves for biographies of famous Black history makers. Fascinated by accounts of the lives of men like Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, McLemore yearned to learn more and more, a desire that followed him when he enrolled in high school at Delta Center School in Walls, Miss., which has since become Walls Elementary School.

Upon entering the only recently desegregated Delta Center School, however, McLemore soon learned that the school’s library did not stock any biographies of famous Black leaders like those he had enjoyed in middle school. The school’s principal, Elias Johnson Jr., had also appointed a number of faculty advisers to the student council, for which McLemore served as president, in a bid to control student activity and prevent further efforts such as protests and boycotts intended to integrate additional aspects of the institution.

McLemore took initiative after seeing the conditions at his school, and began looking for a way to organize a protest under the faculty advisers’ noses. He crafted a large number of leaflets detailing his plans and passed them out to students as they got off the bus at school, before they entered the building. The leaflets contained instructions for students to assemble at the gymnasium in protest instead of going to class.

For the next several days, a large number of students spent the entire day in the gym singing songs and speaking to one another. Eventually, the principal relented and agreed to stock Black history books in the library and to reduce the number of faculty advisers, giving students more freedom at the school. The experience proved to be McLemore’s first foray as a leader in the fight for civil rights.

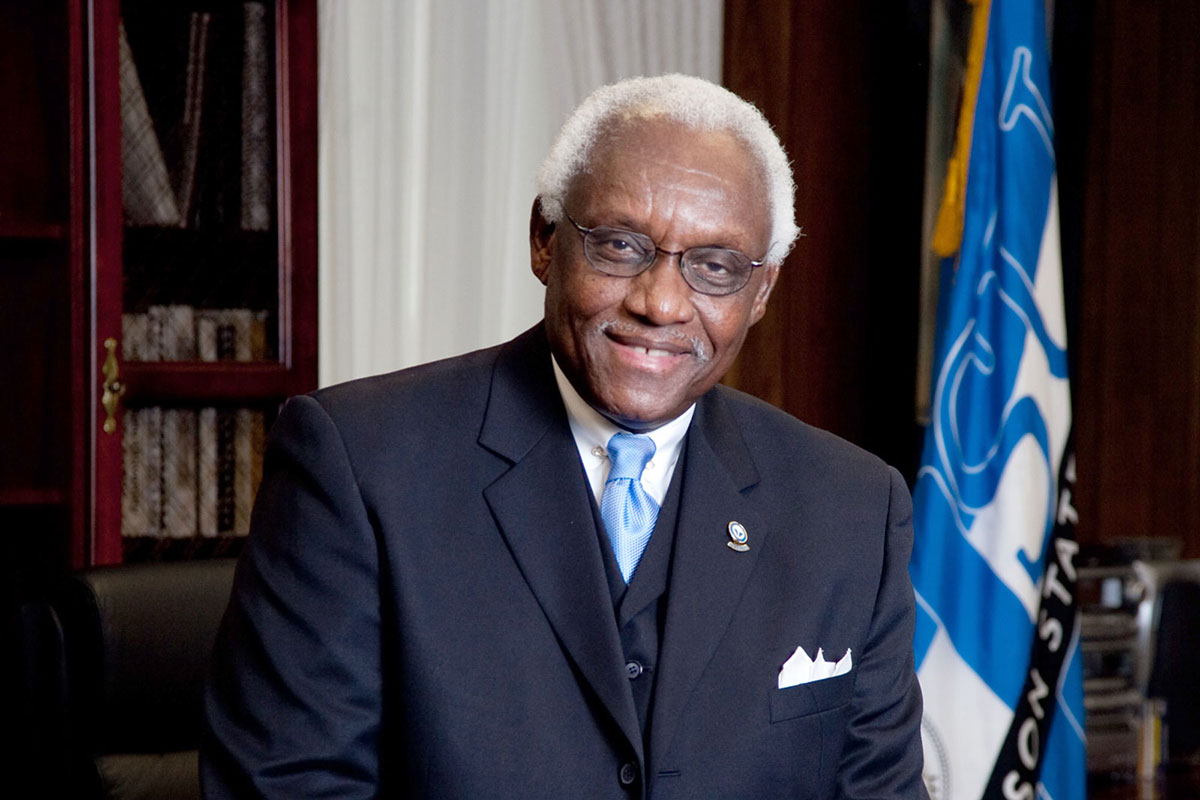

More than 60 years later, the Mississippi Historical Society honored McLemore with its 2023 Lifetime Achievement Award for his efforts as a student leader in the Civil Rights Movement and for his accomplishments as a leader in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

“Generally speaking, I expect folk who have done much more than I feel I have over the years to receive such an award,” McLemore says. “Everything I’ve ever tried to do and have done in the name of social justice was to improve circumstances for people wherever I was, and it was far from my thoughts to receive any awards or special recognition for it.”

“What I am thoughtful of is all the people who have worked with me toward this since my college days and all the institutions I’ve been involved with since,” he continues. “The MHS may be recognizing me, but I consider it a point of pride to have stood on the shoulders of all those who have helped me get here.”

Black Mississippians: ‘Eager to Vote’

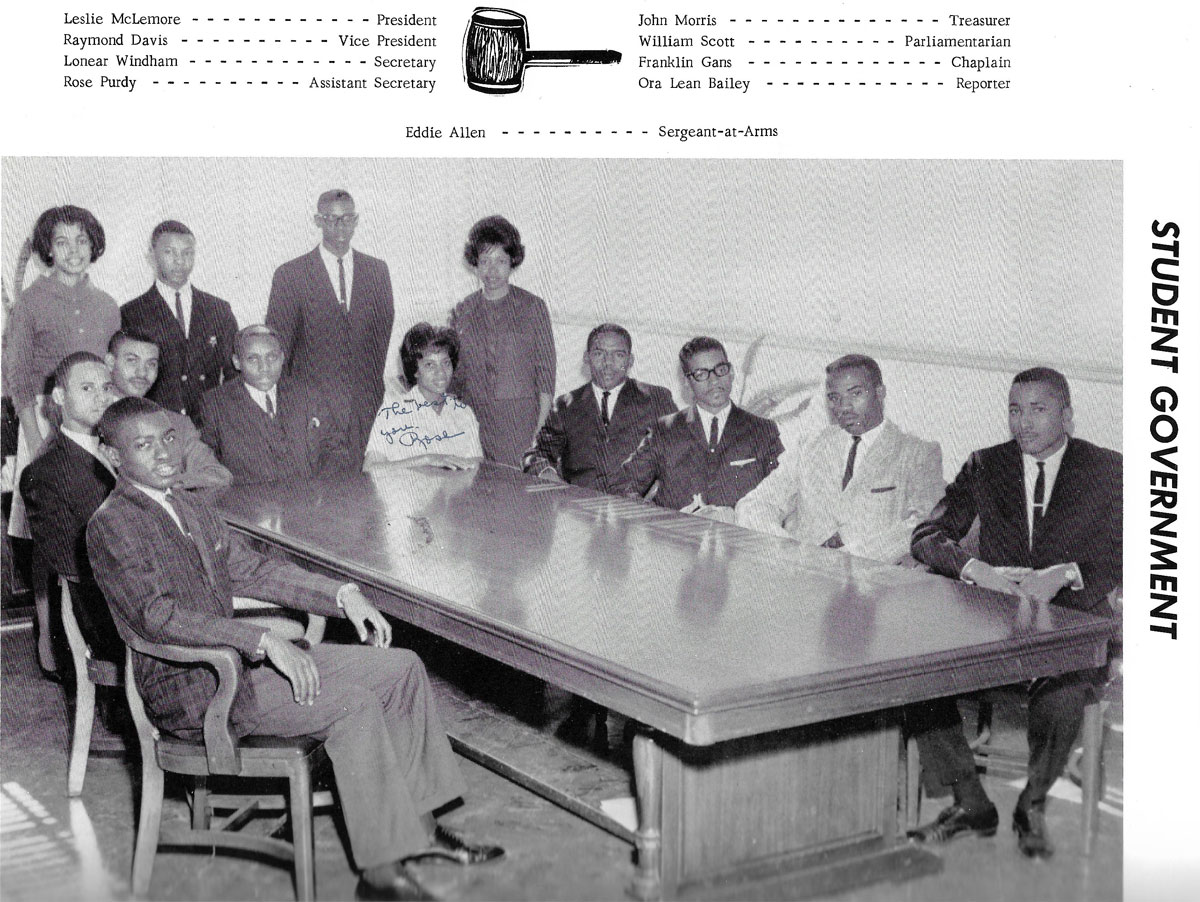

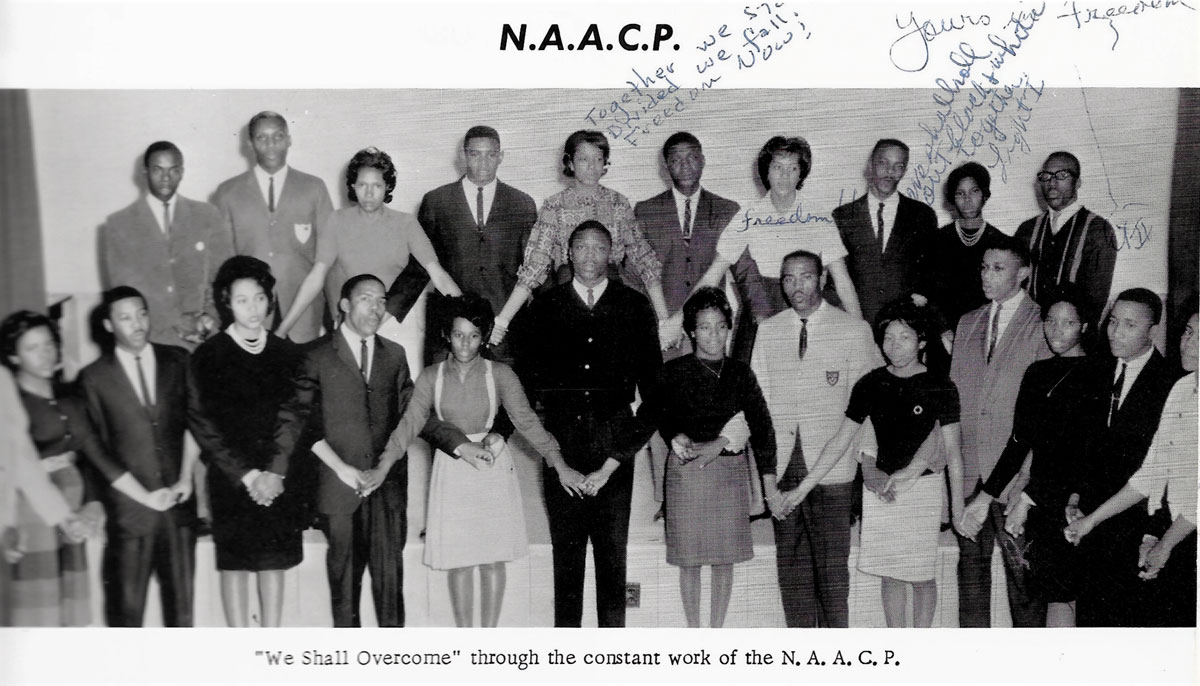

McLemore’s days of civil-rights leadership continued at Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss., where he served as both the first president of the college’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and as a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

While at Rust, McLemore partnered with fellow SNCC field secretary Frank Smith Jr. to host voter-registration drives and to organize the Freedom Vote campaign in 1963—a mock election coinciding with statewide elections that year to raise awareness of Black voter disenfranchisement practices in Mississippi.

“A lot of Mississippi’s white leadership back then were trying to say that Black folk had no interest in voting,” McLemore says. “We demonstrated that they were wrong and that Black folk were eager to vote when given the right. Our efforts in that campaign and the awareness we raised were what led into (the SNCC and other civil-rights groups) organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party a year later.”

The Council of Confederated Organizations—a coalition of organizations comprising SNCC, NAACP and Congress of Racial Equality—founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964 to encourage Black political participation and to act as a parallel political party to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party of that time, who were known as “Dixiecrats.” McLemore served as vice chairman for the organization, which also included civil-rights leaders such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Victoria Gray, Annie Devine, Bob Moses and Ella Baker.

Representatives of the MFDP traveled to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in August 1964 and challenged the Mississippi Democratic Party’s right to participate on the grounds of the state’s segregated election process.

For McLemore, the most prominent memory of that day in Atlantic City is of watching Mississippi native civil-rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer deliver an impassioned speech before the convention’s Credentials Committee.

“Miss Hamer stood before that convention and got the world to see and recognize the living conditions Black people like her faced in Mississippi,” McLemore says. “She spoke about being evicted from a plantation in Sunflower, Miss., about being beaten in jail for her civil-rights work. She captured the imagination of the entire nation that day and put the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party on the map.”

Developing ‘Mutual Trust’ Among All Mississippians

McLemore became the founding chairman and professor of Jackson State University’s political science department in 1972 and served as dean of the university’s graduate school. He also served as interim president of the university in 2010 and became a Professor Emeritus for JSU after retiring from the university in 2012.

He and others also founded the Fannie Lou Hamer National Institute on Citizenship and Democracy in 1997, which aimed to teach high-school teachers and college professors in Mississippi about the Civil Rights Movement through the eyes of those who had taken part in it.

In addition to teaching at JSU, Southern University, Johns Hopkins University and Harvard University, McLemore has served as a member of the Jackson City Council and as acting mayor for the City of Jackson in 2009 following the death of Mayor Frank Melton. He has also served on the Mississippi Municipal League, the Leadership Training Council of the National League of Cities and the Walls, Miss., Board of Aldermen.

McLemore was a plaintiff in a 2019 lawsuit regarding Jim Crow-era electoral requirements dating back to Mississippi’s racist 1890 state constitution. Sadly, McLemore says, the legacy of Jim Crow policies in Mississippi remains an ongoing problem even now, with battles against gerrymandering and other discriminatory practices in the state Legislature taking place.

“The ongoing problem as I see it is that even though Mississippi is composed of 38% Black people, a larger percentage than you’ll see anywhere else, is that all in power now are white Republicans who see the Black population as an ongoing threat to their power, which they don’t want to share,” McLemore says. “This struggle with the powers-that-be has been going on since long before 1890 and will just keep going on until Black people in Mississippi can become better organized.”

“We need to be able to develop a coalition like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. envisioned, where Black and white Mississipians can get to know each other and develop a level of trust between them,” he adds. “Leadership-development programs like Greater Leadership Jackson are a good start, but there aren’t enough of them in other Mississippi cities. We need to all work on projects like these together to develop that mutual trust and bring about meaningful change.”

The Mississippi Historical Society honored McLemore on Friday, March 3, at 12:30 p.m. as part of the society’s annual meeting at the Two Mississippi Museums (22 N. State St., Suite 2205) in Jackson. For more information on the Mississippi Historical Society and the awards luncheon, visit mississippihistory.org.