“Picasso Landscapes: Out of Bounds,” the first solo exhibition of the famed artist’s work to come to Mississippi, weaves a connective thread with a core tenet of the state’s storytellers and artists: the sense of place.

The chronological layout at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, Miss., enhanced via large photographs of Picasso and historical footage that provide 20th-century context, pulls in the sense of time as well and highlights the prolific artist’s scope and spot in the lineage of art history through a landscape lens.

“Picasso Landscapes: Out of Bounds” commemorates the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death at age 91 and will continue to be on display at the Mississippi Museum of Art until March 3, 2024. The exhibition is the 19th presentation of the Annie Laurie Swaim Hearin Exhibition Series at MMA.

The tandem exhibition “Bearden/Picasso: Rhythms and Reverberations” explores shared interests and approaches of Southern-born American artist Romare Bearden and the Spanish-born Picasso, touching on Picasso’s influence and Bearden’s legacy in the art-history continuum.

Laurence Madeline curated and the American Federation of Arts organized “Picasso Landscapes” with the support of the Musée national Picasso-Paris. The Mississippi Museum of Art is its third and final venue. This exhibition is the first major American touring one to focus on the artist’s landscapes, an understudied genre of his that provides a window beyond the cubism hallmarks, figures and faces that most often come to mind when people think of Picasso.

Against the deeply rich hues of the museum galleries’ walls, dozens of Picasso paintings follow the trajectory of a career that stretched across eight decades of art-making, first in his native Spain but soon after across France. A particular place in which Picasso was making works frames each section, MMA Associate Director of Exhibitions Kaegan Sparks pointed out—some that directly influenced his landscapes.

Two early works, created when he was still a teenager in the waning years of the 19th century, picture the mountains of his Málaga birthplace and a dappled grove, made about the time he was joining art academies in Madrid and Barcelona.

“He doesn’t stay there very long. He quickly tries to make his way to Paris,” Sparks said. “He wants to chart his own path, so he’s teaching himself about the Western art tradition but also really wants to gravitate to a place that’s, at that point, the epicenter of new art.”

Picasso visited Paris in 1900 and moved there in 1904. France remained his home for the rest of his life. Paintings, including a window view and a street scene, show the influence of his surroundings including the working-class Montemartre neighborhood where artists flocked (also depicted in historical film clips). Coming on the heels of impressionism 20 years earlier, artists were depicting everyday life with rough, still-visible brushstrokes.

“You get a sense of the materiality of the paint, rather than it just seamlessly creating an illusion of something that’s beyond the painting,” Sparks said.

At times, significant natural events made their way into Picasso’s landscapes, such as a rare snowstorm in Paris (the lovely, sinuous tree trunks of “Snow Landscape,” 1924-1925), and a hillside fire in the French seaside village (“Villa Chêne-Roc at Juan-les-Pins,” 1931) where the artist found much inspiration.

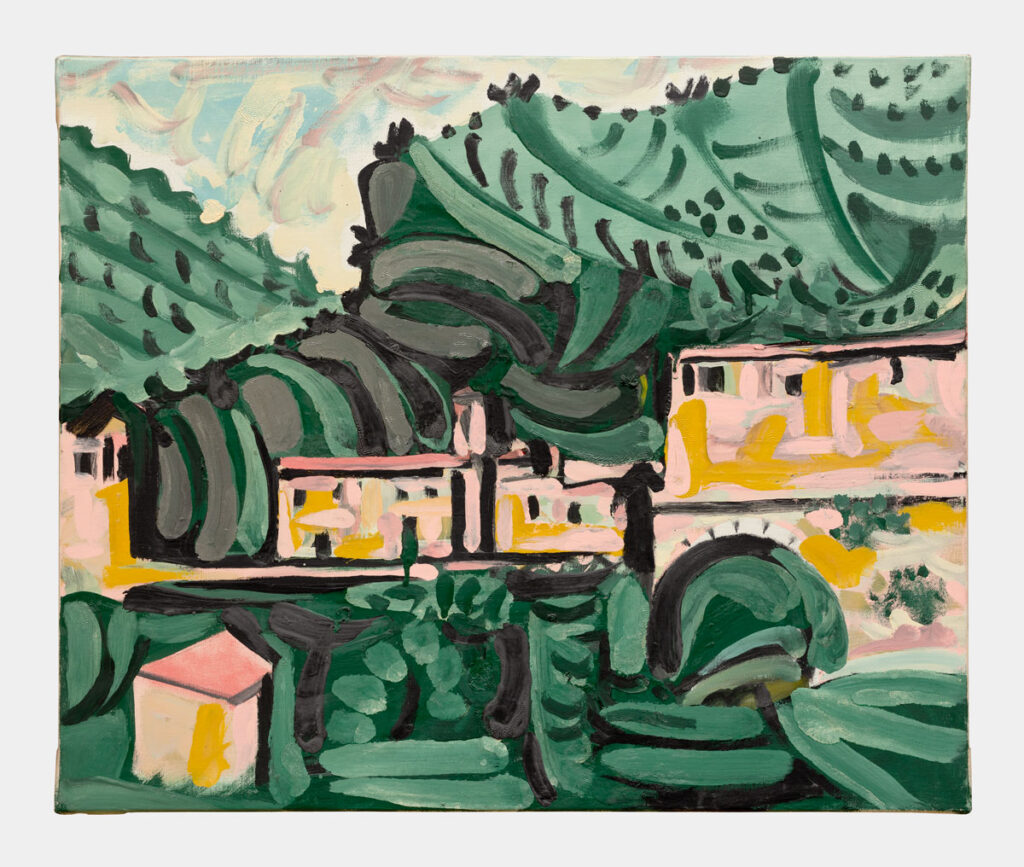

Cubism’s fractured geometrics, multiple perspectives and simplified forms crop up in such works as the deeply verdant 1908 “La Rue-des-Bois” and the Spanish hillside village of the 1909 “Landscape, Horta de Ebro.”

“Picasso is starting to think about different vantage points of objects, combined into one canvas,” Sparks said, “and that becomes a hallmark of cubism,” the influential art style Picasso and fellow artist Georges Braque are credited with creating.

By the 1930s, Picasso had become a well-recognized and successful artist, and two 1932 paintings of the small hamlet Boisgeloup in Normandy, where a chateau became his home and studio, buzzing with the energy of slashing rain. One includes a rainbow brightening the piece. A short home movie featuring scenes of Picasso, his wife at the time and their dog at the estate adds a personal touch.

Picasso’s consideration of sculpture in the landscape folds into the show, with a maquette and a painting of his envisioned—but never realized—beach monuments intended for the shores of the Mediterranean.

“This is a very different style than we’ve seen in a lot of the other works,” Sparks said. “He has a kind of surrealist phase in the ’20s and ’30s; that’s a little bit more about sinuous curves and these figures that look like they’re both organic/natural and also mechanical.”

Figures appear in Picasso landscapes that tap into traditions of Western art such as the “nude woman in the landscape” trope and the pastoral genre. “Picasso is obviously approaching it in a more irreverent way, maybe, than his predecessors, but it’s this whole historical tradition that he’s speaking to and making an intervention into,” Sparks said.

Historical newsreels set the scene for World War II. The gay colors and idyllic mood of PIcasso’s 1940 “Café in Royan” obscure the historical events unfolding around him, Sparks noted. Vintage postcards on display show the pictured building’s landmark role in this French seaside resort, an escape at the start of the war before the artist returned to Paris for its remainder. The painting becomes an unexpected memorial, in the wake of the town’s destruction from bombing during the war. Though life in occupied France limited his environment, landscapes included key Parisian landmarks.

With postwar construction and rebuilding, paintings show the incursion of modern technology and the turnover and redevelopment of the landscape. Hence, a serene balcony view of Cannes at dusk offers birds on the railing; lush, green plants and trees; and in the distance, a villa, the deep blue sea and a construction crane. The exhibition pairs it with a historical photograph showing Picasso at that same studio balcony, juxtaposing art and life.

As with weather events in earlier paintings, “He starts incorporating these other, very historically particular markers that bring what otherwise might feel like a timeless landscape, into the historical context of the postwar period,” Sparks said.

In later years, Picasso bought an estate at the foot of Montagne Sainte-Victoire, a key location and inspiration for artist Paul Cézanne, who painted it many times and was an almost paternal figure in Picasso’s painting career.

One of Picasso’s last exhibitions within his lifetime was installed at a medieval cathedral in France from 1970 to 1972. He placed a landscape in the center, amid a host of figure paintings on the cathedral’s stone walls—as shone in a large photograph of the display, paired with the landscape painting that takes that central spot. Relaying guest curator Madeline’s take, Sparks said, “It has a prominent place. For her, that shows that Picasso has an investment in landscape being part of his legacy and being just as important as the human figure.”

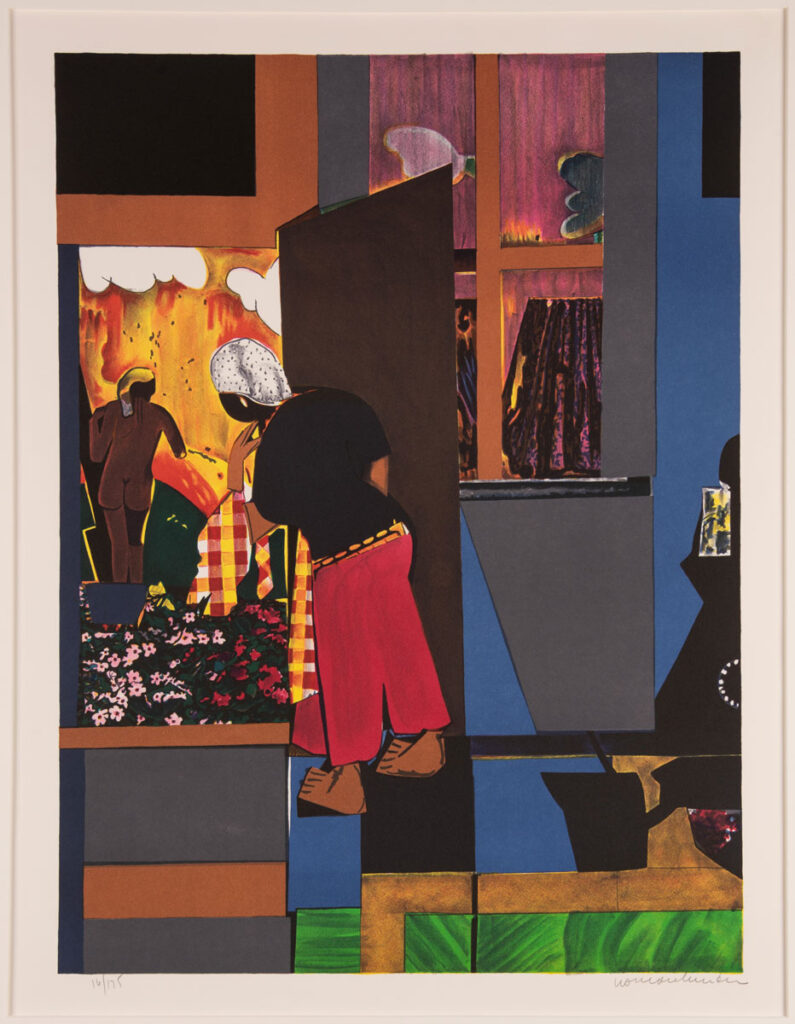

The close of “Picasso Landscapes” flows right into “Bearden/Picasso: Rhythms and Reverberations,” continuing a thread that places Picasso in a larger art-history context. “Bearden/Picasso,” which the Mint Museum in Bearden’s native Charlotte, N.C., organized, focuses on the two artists’ works across four themes: bulls and bullfights, music and rhythm, doorways and windows, and line and color.

Bearden’s career was concentrated in New York, but the African-American artist often drew on memories and the culture of the American South for inspiration in his art. Picasso and particularly cubism also had an effect. “He was kind of a polymath,” exhibition curator Jonathan Stuhlman said of Bearden. “He was a musician; he wrote about art; he was a curator sometimes; he had a career as a social worker for many years; he had the potential to be a professional baseball player. … He wrote about Picasso, (and) he wrote about the cubists’ use of African masks.”

When Bearden went to Paris after World War II to study thanks to the G.I. Bill, he had a letter of introduction to Picasso. They met, but their encounter did not particularly result in a change in either Bearden’s practice or that of Picasso, then a superstar whom many young artists went to see. When asked about it, Bearden replied, “Oh, I went to see Picasso,” Stuhlman explained with a chuckle. “Like one goes to see the Eiffel Tower, like it was kind of a mandatory tourist stop.”

Picasso’s “The Bull Fight” and a wildly colorful pair of Bearden’s on the same subject open this exhibition with a riveting punch, in the frenzied, violent clash of animals and flighter. Western art has a tradition of showing bullfights, but Bearden found inspiration, in particular, in a poem the Spanish poet Garcia Lorca wrote titled “At Five in the Afternoon” (also the title of one of Bearden’s paintings).

“It’s a really interesting kind of triangulation between the three,” Stuhlman noted. Lorca used the bullfighting arena as a metaphor for violence in the Spanish Civil War. Picasso’s famous “Guernica” mural, exhibited in New York, protested the war’s violence. The title of Bearden’s painting, “Now the Dove and the Leopard Wrestle,” quotes a line from Lorca’s poem, and its screaming horse, gored by a horn, quotes the panicked horse in “Guernica.” In Bearden’s “Conjur Woman as Angel,” a watchful bull looms in the background—a masculine counter to the healer and the woman she is treating.

Musician images recurred in the works of both artists, and Bearden’s “Back Porch Serenade” and “Evening of the Grey Cat” resonate with Southern-rooted memory and pulse with warm and lively visual rhythm. His interiors, highlighting doorways and windows, pack the power of story, and bold lines and colors in “Madonna and Child,” “The Annunciation” and more carry forward the stained-glass aesthetic.

Both exhibits showcase multidimensional artists and their explorations in styles, subjects and artistic traditions. “Artists don’t operate in a vacuum, and they are always looking around them—to their environment and particularly to their artistic past—for sources of inspiration to continue a certain trajectory, or to react to and try something new,” Stuhlman said.

“Picasso’s one of the most important artists of the first half of the 20th century, and Bearden, in terms of American art, he’s certainly one of the more important artists of the second half of the 20th century,” Stuhlman said. Bearden is particularly known for reviving the collage medium that cubists had pioneered 50 years earlier. He used it to explore his own cultural heritage and the lives of Black people in the South. The exhibition, Stuhlman said, “was a nice opportunity to bring Picasso’s influence home, in a way.”

Admission for “Picasso Landscapes” and “Bearden/Picasso” is $18 for adults, $13 for people aged 65 and above, $10 for children between the ages of 6 and 17 and college students with student IDs, and free for museum members and children ages 5 and under. The Mississippi Museum of Art is located at 380 S. Lamar St. in Jackson, Miss. Learn more about the exhibit at msmuseumart.org/exhibition/out-of-bounds.