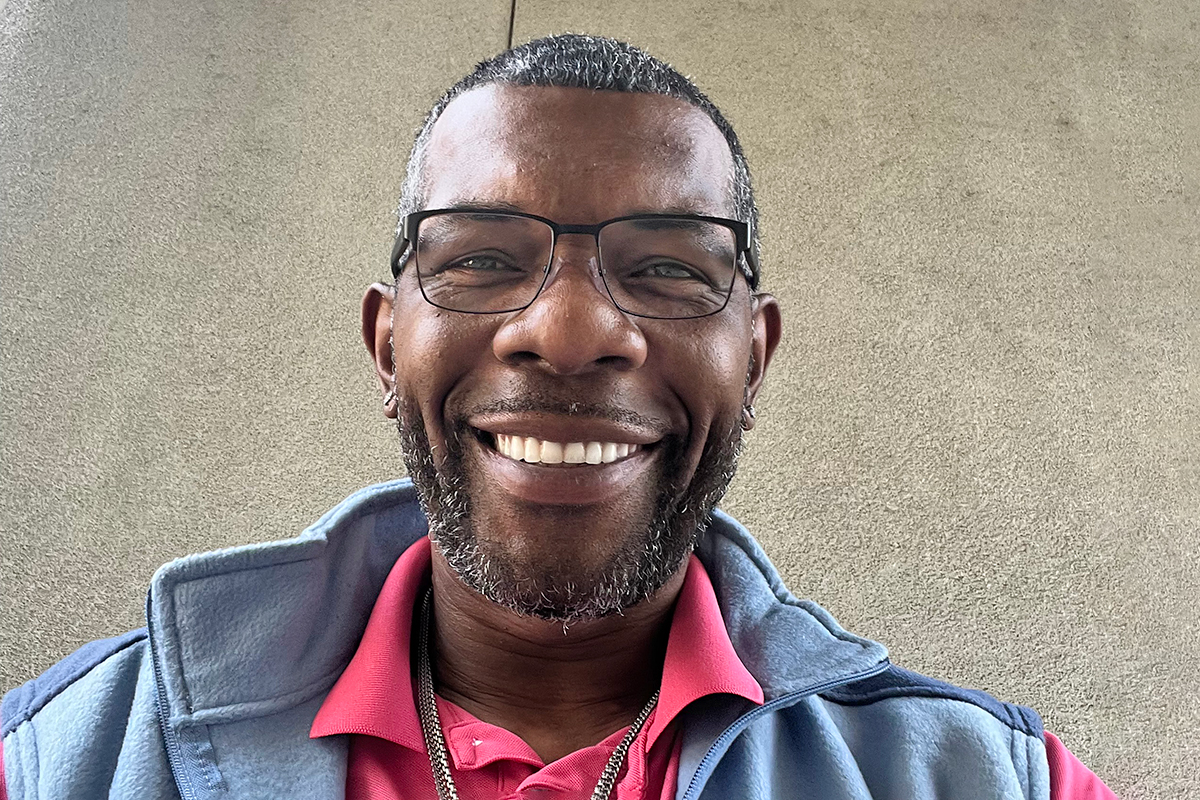

When John Knight left jail for the third time in 2013, he owed about $40,000 in child-support payments on seven different children from seven women. The first of the seven children was born when he was about 16. He is now 45.

“I think I was in 10th grade when I first got put on child support in 1994,” Knight told the Mississippi Free Press over the phone on March 18, 2022. “So, I have been dealing with the court system with child support for 20-something years. I got out of high school in 1995, but I went to prison my first time in ’96.”

Knight describes a child-support system that was near impossible for him to get in front of and made the trajectory of his life more difficult—with him over time less able to support his children, a cyclical problem even Black women’s advocates in Mississippi warn about.

Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable Co-convener and State Lead Cassandra Welchlin told the Mississippi Free Press by phone on March 15, 2022, that while mothers are typically the primary caregivers for their children, the accrual of child-support debt for the incarcerated non-custodial parent adds to the individual’s financial load and strains the relationship.

“If they don’t pay this debt off, they’re going right back into prison, you know? And so, this would be, again, harmful to that relationship and also (affects) that mom getting the resources that she needs in order to take care of that family.”

As a teenager, Knight worked at Rally’s on Highway 80 in Jackson, Miss., where he remembered earning less than $5 an hour and about $600 a month. He later received a paycheck $215 less than he expected. The reduction was because of a child-support obligation removed from his paycheck.

“I quit the job because of child support—it was eating my check up, and I was a kid; I wasn’t grown; I was a teenager still living with my mom,” Knight continued.

“My auntie was a manager. So she helped me get a job there to try to put a few dollars in my pocket. But as soon as I got it, they garnished it out of my check, so it was just a losing situation at an early age.”

Quitting the job and moving to the street to sell drugs, Knight repeatedly landed in prison before starting a journey to rebuild his life outside incarceration. “[I]n the process of me being incarcerated all the years all three different times, child support never stopped, never stopped coming,” he said.

He remembers getting child-support bills from the Mississippi Department of Human Services while in prison. “So I took it upon myself a couple of times to write them, ‘’[I] am in prison. How can I pay y’all, and I’m incarcerated in prison?’” Knight added. The department has recently been embroiled in financial misappropriation controversies.

An MDHS publication titled “Division of Child Support Enforcement Child Support Policy Manual” provides an avenue toward a potential remedy on pages 295 through 299 for people who are in prison.

As stated in MDHS’ manual, a child-support worker shall notify an inmate sentenced to more than six months in prison that it is possible to request a review of the child-support amount within 15 days of the worker learning of the sentence. How the worker learns of the inmate’s incarceration status is unclear.

The prisoner must then send a written request for review to MDHS, and the child-support worker will then send a letter informing both parents of the decision to either grant or deny the request.

Not being able to locate the custodial parent means the review remains pending. The custodial parent can challenge the assessment in writing within two weeks of receiving the decision, and the worker must notify the inmate of the challenge not more than two weeks after the custodial parent submits the challenge.

A supervisor will review the challenge and make a final decision. If the supervisor agrees to the review, MDHS will transfer the case to an attorney on staff who will obtain an adjusted order from the court.

MDHS will subsequently mail an agreement stipulating the new order to the inmate within two days. DHS requires the incarcerated parent to send a signed and notarized stipulated agreement to suspend child support to the child-support worker, who will refer it to the legal department to obtain a court order approving it.

If the inmate does not send in the notarized order within 60 days of DHS mailing it, the expedited review process, created for those in prison, will terminate it in that case. “Upon receipt of the properly-signed agreed order within sixty (60) days of mailing, the (child support department staff) attorney will present the same to the Court for approval,” the MDHS document added.

MDHS policy states that if the correctional facility does not have a notary, the case should be immediately referred to the child-support attorney to file the appropriate petition and mail the proposed agreed order to the noncustodial parent. How DHS will determine if a facility offers notary service or not is unspecified.

“If a case is eligible for modification of the current child support order on the basis of incarceration, a modification may be initiated by the agency without a request from the noncustodial parent or the custodial parent when appropriate,” DHS wrote. The parameters that constitute when the situation is “appropriate” are undefined. Additionally, the language does not specify that MDHS must do it, as the text only says that it “may” do so.

John Knight said it is difficult for those in prison to navigate that process. “[I]nstead of them taking it upon themselves to do the right thing and stop child support until this person is released, they let it pile up and pile up and pile up, and then you’re forever stuck,” he said.

In a February 2022 report, the National Conference of State Legislatures explained that incarcerated parents with child-support obligations are often unaware of child-support debt while locked up. Many states, including Mississippi, require those in prison to be aware of child support policies and submit paperwork, constituting a barrier to modifying the child support orders, it says.

“Even when obligors are aware of their right to modify child support orders, knowing the process can be a challenge,” the organization wrote. “Obligors sometimes do not become aware of modification opportunities until they have already served their time or are nearly finished.”

A newly released parent may confront a mountain of child-support arrears on top of having difficulty finding work due to their felony record. When trying to avoid returning to prison for contempt of court for child-support nonpayment, returning to crime may appear to be one of the only options.

“That means that they’re going to continue to be pushed back in that corner to continue to do the same thing they did to go back to prison because they need to try to pay this child support, (because) they need to try to get their driver’s license reinstated, (and because) they need to try to pay a certain amount of money every time they go to court,” Knight said.

Knight believes the criminal-justice system sets up people to be perpetually behind bars. “(Obligors will) be in so much debt with their child support that any job they get, they might get their first check or maybe their second check, and after that, they are going to ‘kill him’ (with garnishment).”

“So it’s a lose-lose situation when you’re incarcerated and have child support, only because it’s not going to stop, it’s not going to stop while you’re incarcerated,” he added. “It should, because you’re in jail—you don’t have a job; you can’t pay it. So why would y’all tax them or charge them when they are locked up, and they can’t pay it?”

‘A Common-Sense Approach’

Mississippi House Bill 592, which would have suspended child-support payment for those in prison, passed in the Mississippi House of Representatives on Feb. 14, 2022. The law does not cover those who have the resources to make the payment or who are in prison for child abuse or for not paying child support.

Re-entry reform advocates gathered inside the Mississippi Capitol one week after to advocate for the bill.

At the event, RECH Foundation CEO Pauline Rogers called the bill “a common-sense approach to eliminating barriers to re-entry,” adding, “Incarceration should not be regarded as voluntary (unemployment).”

MDHS refers those who receive federal benefits to its child-support office. In spite of federal guidelines decreeing that states should not treat incarceration as voluntary unemployment in their operations of child-support service, Mississippi continues to charge those in prison for child support, even though they have no income.

The State continues sending child-support balances to those behind bars, except on an order from a chancery court. House Bill 592 would emplace the automatic suspension of child-support billing for someone sentenced to more than six months in jail. The bill did not make it to the floor of the Senate for a vote.

‘It Would Have Been a Good Bill’

Mississippi Black Women’s Roundtable Co-convener and State Lead Cassandra Welchlin told the Mississippi Free Press that the bill’s death was regrettable.

“It would have been a good bill and smart policy, a really smart policy,” she said. “Just to give returning citizens the opportunity to get a job and not have to carry that large amount of debt, but really try to start afresh and resume paying the child support so they can take care of their families and reintegrate back into their family’s lives, their children’s lives.”

“And then when you have a disproportionate amount of Black people incarcerated, removing any kind of financial burden would just be a win-win for the returning citizen and for that family,” she added. “They can’t pay anything while they’re incarcerated. And so it makes no sense to continue that debt.”

Do you support suspending child support payment for those in prison (I welcome your comments for whatever choice you make)

— Kayode Crown (@kayodecrown) March 30, 2022

The Mississippi Department of Human Services lists several child-support collection enforcement methods including income withholding, interception of unemployment benefits and court action finding the parent in contempt, which may result in imprisonment, the organization says. Others include license suspensions including drivers and work license, and passport revocation.

This reporter created an unscientific twitter poll on March 30, 2022, asking for responses to the question: Do you support suspending child-support payment for those in prison? By the end of the poll’s 48-hour period, 157 people responded. About 49.5% voted in support of it, while 24.8% said no and 26.8% were unsure.

In a phone interview with the Mississippi Free Press on March 12, 2022, Mississippi Rep. Gene Newman, R-Pearl, said he is not interested in getting those incarcerated off the hook for child-support payment during their time behind bars.

“I’m not for letting people out of child support,” he said. “if you’re gonna go out and have a child and you need to support the child, and you need to do what is necessary to do it.”

“Just because you make a mistake, and you’re gonna be locked up, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t still be supporting the child.”

Jackson-based attorney Peter A. Stewart III disagrees with Newman, and explains why he thought HB 592 would have been valuable. “In my opinion, we needed that bill; we needed it desperately,” he told the Mississippi Free Press. “In my opinion, it is common sense.”

“There are employers that will not hire someone who has basically a felony amount of child-support arrearage,” he added. “And so there’s certain things you just can’t do because literally the dollar amount of the child support hanging over your head could be turned into a felony. You could be snatched up at any time.”

John Knight said that he recently discovered that he should have stopped paying child support for his children, who were between ages 22 and 27 years.

“All seven of my cases were over 21 years old,” he said. “There were 25, 28. So that’s six, seven years that I was supposed to have stopped paying it and just been paying arrears, but they didn’t do it that way.”

When the Mississippi Free Press reached out to the MDHS on March 31 about the childhood-support payments, the organization sent this statement via email on April 1, 2022: “Child Support obligations are ordinarily paid through wage withholding orders. The money is collected and distributed to the appropriate party, and accurate payment records are maintained.”

Knight, however, said he experienced more than MDHS described. “They had continued for me to pay the obligation and the arrears and the court costs and the lawyer fees (beyond 21 years of age of the child) and all those things I tell you that they add to keep you in bondage.”

It wasn’t until the last two years, when he became a juvenile counselor and a truancy director at Henley-Young Detention Center in Hinds County, that Knight came in contact with some lawyers who helped him navigate the judiciary system and was able to stop his continued child-support payments. He discovered that he had overpaid and has not received any refund.

“I’ve been paying child support since 1994 until two years ago,” he said. “I had like seven cases. I overpaid on cases. They don’t want to give me back the money that I paid over, but they were so quick to take it.”

“They need to revamp their whole damn system. I’ll stand up in front of the United States Congress, in front of the whole world and be the poster boy and be the spokesman for how child support does you and has done me and other people.”