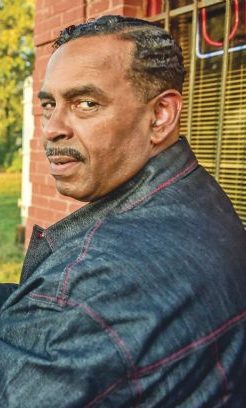

After applying for 43 vacancies in northern Mississippi and being denied every one of them after his time in prison, former Columbus, Miss., Councilman Kamal Karriem is now advocating for the business community to open its doors to people like him as a measure against recidivism.

“Now, because of my criminality and stigma that society has put on me, I can’t even get a job frying chicken,” he said at an online event. “I had to roll barbecue grills many days on street corners—selling barbecue, washing cars, doing whatever I could do because I could not be hired despite my college education because of criminality, even though I had served my time.”

In 2005, while a councilman, Karriem pleaded guilty to embezzlement for lending someone a city-owned cell phone. After the person ran up a $500 bill, Karriem spent two years in prison and eight years on parole.

“People that have already done their time, they’ve already served their time. Why should they be punished for the remainder of their lives and be treated as a second-class citizen and be ostracized from places in society?” he asked during an Oct. 27 virtual workshop titled “Criminal Justice in Mississippi; Where We Are and Where We Need to Be.”

Karriem joined 16th Circuit Court Assistant District Attorney Trina Davidson-Brooks and Vera Institute Outreach Associate Sarah Minion for the conversation. The 16th Circuit covers the 200,000 people in Lowndes, Oktibbeha Clay and Noxubee counties.

One Voice Mississippi organized the event at its annual Mississippi Black Leadership Summit. Matthew Campbell, community organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Mississippi, moderated the workshop.

‘They Can Still Be a Citizen’

Trina Davidson-Brooks said assisting the formerly incarcerated is vital so that they can break the cycle of criminality, rather than return to it when they cannot find employment. Businesses need to hire people with criminal records to build a better community, she added.

Mississippi has a 33% three-year recidivism rate and a 77% rate for five years, worldpopulationreview.com indicates. The recidivism rate is the percentage of prisoners who, after their release, return to prison because they have committed another crime. Mississippi has the second-highest incarceration rate in the United States at 638 per 100,000, following Louisiana.

“Even though they paid their ‘debt to society,’ they still have to live, and they can still be a citizen in our community,” Davidson-Brooks said. “They made a mistake; that mistake does not have to enslave them for the rest of their life.”

In 2015, the City of Jackson, Miss., instituted the “ban the box” initiative and stopped asking job applicants about prior felonies during the initial steps of the hiring process, Human Resources Director Toya Martin told the Mississippi Free Press in an emailed statement on Wednesday, Nov. 3. “However, we do notify candidates that if they are selected for hire, they will have to undergo a background and drug test,” she added.

Fifteen states have mandated the removal of conviction-history questions from job applications for private employers: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington. The National Employment Law Project, which reported that data, said 37 states and more than 150 cities and counties have adopted the measure.

Business Community Involvement

Before prison, Karriem pastored a church. After completing his sentence, he applied to a number of businesses and organizations, with all turning him down. On his 44th attempt, Karriem found a position within another church, ending his long-standing job hunt.

Karriem said the state’s business community has a role to play in helping the formerly incarcerated rehabilitate and re-enter society. By helping those who have served their time find work, he argued, Mississippi can halt the revolving door back to criminality that some face when presented with few alternatives.

“The business community has the excuse not to get involved because of the criminality of just being in prison,” he said in October. “But I think we’re going to have to convince the business community that if you hire someone who has done their time, what you are doing is you’re not taking away from your business; you’re enhancing society, and you’re helping this person (with) reentering and getting back into the mainstream.”

Karriem also advocated equipping the formerly incarcerated with the requisite skills they could use to be relevant in the business world.

“We’re going to have to make an appeal to these corporate boards to take in so many who have been formerly incarcerated,” he said. “But, we have to make sure that those who have been incarcerated, that they develop a skill set that they can meet the (business’) need.”

Karriem wants vocational training and four-year university training for the formerly incarcerated to gain in-demand skills.

Hinds County Reentry Program

On Oct. 12, Hinds County’s reentry program admitted 21 Mississippians deemed at risk of going back to prison into its maiden months-long cognitive- and workforce-development program with many businesses supporting the efforts by lining up to employ those who have completed their training.

“We have met with employers who have agreed to hire our graduates, so when they graduate on a Friday, they start working on a Monday,” Hinds County Reentry Program Director Louis Armstrong told this reporter on the phone on Oct. 6. Participants will choose from one of these areas: construction, manufacturing, warehousing.

“In areas that have started reentry programs in recent years, the immediate impact is a 30-35% reduction in crime due to a reduction in recidivism,” added Armstrong, who was formerly incarcerated for one year in federal prison for receiving bribes as a Jackson City Council member to influence a vote in 1999.

Money Needed to Pay Parole Officer

Kamal Karriem said the formerly incarcerated need the jobs to pay their parole officers so that they don’t go back to prison if they fall behind.

A Flowood, Miss., Municipal Court judge found Savannah Willis, a poet and docent at the International Museum of Muslim Cultures in Jackson, guilty of driving with a suspended license and resisting arrest and sentenced her to six months probation in 2019. She told this reporter in 2020 that she paid $50 each month to the probation officer, apart from $1,700 in fines.

“You need to give formerly incarcerated people a chance, particularly those that have been convicted of nonviolent crimes and who just want to be able to make a living, who just want to be able to pay their parole officer,” Karriem said in October. “Cause if they don’t pay their parole officer, guess what? They’re going to get locked up again.”

Restorative Justice

Trina Davidson-Brooks explained the changes that District Attorney Scott Colom has made to the functioning of the office since his election. Colom defeated 26-year incumbent Forrest Allgood for the position in 2016 and won re-election without any opposition in 2019.

Apart from moving first-time nonviolent offenders to a diversion program to embark on personal reforms and self-development in exchange for record expungement, Davidson-Brooks said last week that the district is implementing a restorative-justice program.

“If someone commits a crime, the (usual) ‘justice’ is punishing that person, but with restorative justice, the method is a little bit different, and it focuses on the harm that was caused by the crime that was committed,” she said. “You’re able to bring both parties—the victim and the person who caused the harm—together.”

The victim and the one who committed the crime meet face-to-face, “and you have a restorative-justice facilitator who facilitates the process,” she explained, with the victim expressing the harm suffered by the crime.

“We’ve had cases where we’ve had ‘restorative-justice circles’ and the victim just wanting to hear the person who harmed them say, ‘I’m sorry,'” she said.

“Once they’re able to get that from the person who did that to them, a lot of times they say, ‘You know what, he’s apologized. I want my restitution for whatever damage (caused) or what was taken, but I don’t want to see this person go to jail because I think that he or she is sorry, and there’s no jail time needed,’” she explained.

In a Tuesday, Nov. 2, statement to the Mississippi Free Press, Davidson-Brooks said that the district’s Restorative Justice Facilitator Tina Rogers has taken the lead in 11 “restorative-justice circles” since late 2020, with cases ranging from burglary to murder, boasting what Davidson-Brooks claimed as a 97% success rate.

“Due to the type of harm caused by the defendant in any given case, we are very selective of the cases we allow to participate in the circles as we do not wish to harm them any further,” she wrote. “As a side note, depending on the severity of the crime, not all restorative justice circles will result in the Defendant not going to jail.”

Examples of Restorative Justice

The assistant DA wrote about three cases that went through the restorative justice process—a car accident, church burglary and second-degree murder. Davidson-Brooks said a family believed a young woman who left the scene of an accident murdered their loved one.

“In the circle, there was a great breakthrough whereas the mother of the deceased told the defendant that she forgave her,” the attorney wrote.

“The defendant was sincere in her apology to the mother,” she added. “She explained what she should have done differently and how this has impacted her life.”

“At the end of our circle, they cried, hugged each other, and decided that they would stay in contact,” she added. “The victim’s mother in this case strongly opposed the defendant going to prison and wanted something different, so we concluded the circle.”

“That recommendation was sent forth to the appropriate parties.”

For the church burglary, the pastor of the affected Noxubee County church stood in as the victim and asked the defendant various questions.

“The defendant let him know that he has some struggles but now has gainful employment, has a new love in his life, and how he intends to repay all that he owes to the church,” the assistant DA wrote. Because the pastor felt that “the defendant was truly sincere,” he asked for no prison term.

“The defendant was in tears and eternally grateful for the decision the pastor made at that time,” Davidson-Brooks said.

For the second-degree murder case, the victim side of the circle, which the family of the deceased comprised, listened as the defendant gave details of what happened the night their loved one died.

“[I]t was so compelling to see a person who was harmed speak on their feelings about the hurt, harm, and pain caused by the defendant but also understand the importance of truth and how truth sets you free,” the attorney wrote. “After this circle, the victim wanted to speak to the District Attorney to recommend no more than twenty-five years.”

“The victim felt that would be enough time because no amount of time would bring their brother back.”

Restorative Justice in Massachusetts

Winthrop, Mass., Police Chief Terence Delehanty, in a report by wcvb.com, hailed a nonprofit working in the city—Communities for Restorative Justice, or C4RJ—for its impact.

The programs bring mostly juvenile suspects, victims, police, and supporters together “to promote healing and a resolution that holds the suspects accountable without an arrest or jail time.” C4RJ works with police departments in 31 Massachusetts cities and towns, mostly Suffolk and Middlesex counties.

“It’s about giving children a second chance in life and making them understand how to make those right decisions in the future,” Delehanty said in the Oct. 27 report. “They’ve been very helpful to Winthrop. We’ve referred a lot of cases over to them, and a lot of these cases are misdemeanor juvenile cases or assault and battery, kids fighting, shoplifting.”

North Carolina Department of Public Safety Juvenile Court Counselor Shalee Forney wrote on July 5, 2021, on socialworker.com that restorative justice ensures the victim is the center of the processes.

“Across the nation, the victim’s voice is replaced by that of the prosecutor, who essentially represents the victim,” she wrote. “Victims often feel excluded throughout the process, including sentencing.”

“Those victimized generally have no say in how crimes have affected them,” she added. “For true justice to be served, all parties need a chance at restoration.”

She said research has shown that offenders and victims feel empowered to repair relationships and develop a new sense of understanding via the restorative-justice process.

“[E]ach person is allowed to share their story and speak from the heart,” she wrote. “The goal of this process is to promote healing, facilitate the offender in making amends, empower victims, and build a sense of community.”

“According to a study conducted by Umbreit (1994), victims who participated in this process were more satisfied than those in the court system,” she added. “Victims felt less fearful of being re-victimized in the future. Offenders who participated were more likely to complete their restitution obligations.”

Restorative Justice and Accountability

Restorative justice holds the individual accountable and does not preclude jail time, or probation in some cases, “but a lot of the times, you can avoid all of that,” Trina Davidson-Brooks said.

“You can avoid incarceration if you (bring people) together and have a resolution and a just outcome,” the assistant DA continued. “And in those situations, I think that it’s justice, right? Because you’re holding the person who committed the crime accountable, and you’re also offering forgiveness.”

“The person who committed that crime does not get a conviction, and you can prevent people from going into the system by just having an alternative way to resolve a conflict because that’s what most of it is,” she added.

“And also taking a look at and trying to embrace restorative justice, understanding it and understanding the need for it to help, not only the victim, but to also hold the offender accountable for his or her action, and still not have to necessarily incarcerate that person.”

Editor’s Note: District Attorney Scott Colom and his father Wil Colom have previously donated to the Mississippi Free Press. That had no influence on this reporting.