The prolific Black journalist Ida B. Wells toiled for justice in Memphis and across the world, speaking out against lynching and the unfair treatment of women and Black people.

“Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” said Wells, in whose honor a statue will be unveiled Friday morning July 23 on Beale Street.

The vigilance she speaks of doesn’t assume every act is sinister, but it does implore us—especially journalists—to listen when disenfranchised people speak out, to be relentless in pursuit of truth in any issue, and never dismiss the plight of historically overlooked people.

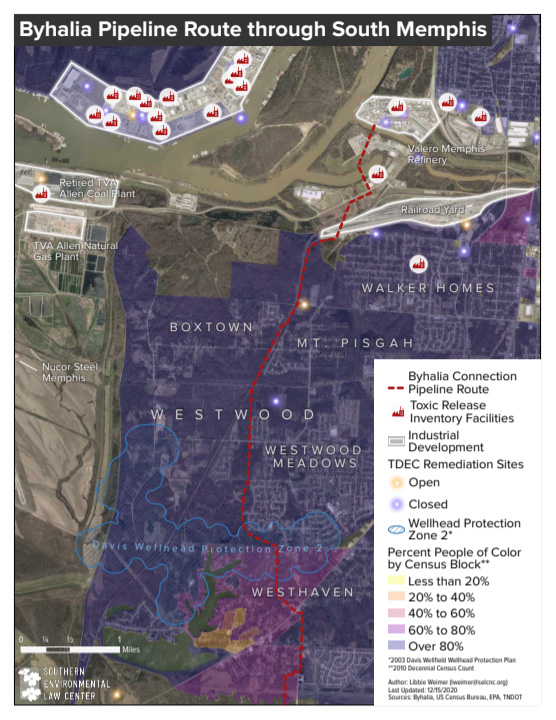

Consider when Plains All American Pipeline announced in late 2019 its joint plans with Valero Energy Corporation to build the Byhalia Connection Pipeline through Black communities in Southwest Memphis. The multi-billion-dollar fossil fuel corporation, with a public relations machine, blitzed into Southwest Memphis with maps, charts and donations to local nonprofits, as though the pipeline was inevitable.

And it might have been had Boxtown and other communities not vigorously wrestled the company in a battle of information to make their health and property concerns heard by elected officials and media.

The company tapped out and announced on July 2 that it would not proceed with the project.

Early news coverage of the pipeline mentioned the company’s plan, community meetings and featured residents of North Mississippi, where most of the pipeline route would have run.

Few stories explored what a pipeline would mean for the Black, low-income Memphians in its path and the risks that it could pose. The residents were not just espousing unsupported fears; they were telling Memphis what they know through the experience of environmental degradation that spans generations. And those accounts are backed up by numerous studies as researchers and policymakers catch up to the realities of environmental injustice.

Additionally, few stories applied journalistic scrutiny to the company’s promises regarding the project’s benefits to the area.

MLK50: Justice Through Journalism centered Boxtown’s opposition in its first two stories about the project written last fall by freelance journalist Leanna First-Arai. The stories caught the attention of former Southwest Memphis resident Kathy Robinson, who sent it to another former resident Kizzy Jones, who shared it in a Mitchell High School alumni Facebook group where Justin J. Pearson, also from the area, read it.

Those stories brought together the three eventual founders of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline, and they attended what would be Plains’ last community meeting, in November.

Knowing that the pipeline would run through the places they grew up and where their families and friends still reside led the trio to fight. Boxtown residents, many of whom are elderly, accepted the help of MCAP after elected officials ghosted the neighborhood associations’ previous efforts.

Months later, MLK50 was first to report on Plains’ use of eminent domain in Memphis to force access to land that owners wouldn’t sell to them. The frustration and pain of the residents came through in story after story, including one about a landowner who sued the company, alleging that a Byhalia Pipeline agent took advantage of her medical emergency to have her sign away an easement.

Another story, co-published with the Guardian and Southerly, took a broader look, calling the Byhalia Pipeline fight a “flashpoint in a national conversation about environmental justice and eminent domain.” The fight had already gained national attention, including from celebrities Justin Timberlake and Danny Glover, former Vice President Al Gore and the Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.

As the stories continued and more information about the company’s use of eminent domain and the risks of a spill became apparent, local politicians—who previously would not respond to residents’ requests for support—jumped on board.

Knowing the stories of property owners changed Westwood pastor the Rev. Melvin Watkins’ opinion on the pipeline.

And knowing the pipeline would have added risk to the Memphis Sand aquifer made Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland an opponent, but this was after the community’s many requests for his help.

The saying is that “knowing is half the battle,” but for the Byhalia Connection, knowing seemed to be all of the battle for pipeline opponents.

Community Determination

At a November community meeting, Jones asked company representatives what residents would need to do to have Plains abandon its plans. One representative was Deidre Malone, a former Shelby County commissioner and public affairs consultant hired by Plains. At the same time, Malone served as second vice chair of the NAACP Memphis Branch, which accepted a $25,000 donation from developers.

Malone told Jones she didn’t know what it would take to stop the pipeline and that there is a “strong possibility” it would be built, and that the community should instead dialogue with the company on how to “work together.”

Plains representatives did not consider the option of not building a pipeline because the community doesn’t want it since fossil fuel companies historically have never been required to care what poor Black communities think of their business.

If a landowner doesn’t want to sell access to an oil corporation, the company can simply force their way onto the property through eminent domain. “No” was never a real option for someone who can’t afford to stand up to the multi-billion-dollar company in court.

Southwest Memphians should be able to veto projects that pose an immediate risk for their community. Furthermore, low-income communities of color should not be forced to host a contributor to a climate crisis from which they will be first to bear the most severe consequences. And the veto should be backed by elected officials and government institutions.

A Plains land agent said the route through the area was chosen because it was a “point of least resistance.”

The infamous one-liner highlights a fundamental question that’s larger than Memphis. Should Black people—including those with low wealth—control what goes in and out of their communities?

Some would say, yes, Black people should control the economics and politics of their community. But Plains representatives have argued that the pipeline was opposed by only a vocal minority.

I made cold calls to landowners who sold easements to the company in an effort to find a landowner or resident in the path of the pipeline that would say they were excited about the project. To this day, I’ve found none.

The Daily Memphian posed the question of whether pipeline supporters were being “drowned out.” But even that story did not include a single resident who publicly supported the project, only an anonymous Boxtown resident who said they were neutral.

I even turned to Plains’ representatives and asked to be connected with a landowner in support of the pipeline. They didn’t provide a landowner, and one representative responded saying, “Based on MLK50’s previous coverage around the project, I’d like to better understand your intentions.” However, no representative accepted calls or returned emails to discuss further.

No community is a monolith, and my goal is to amplify the voices I encounter in my reporting. The only Memphian I encountered who publicly claimed to want the pipeline was Malone, a public affairs advisor for Plains, and she declined to be interviewed.

What happened here sent a message: Billion-dollar companies must respect the agency and dignity of the people who would host their projects, regardless of their race and access to capital. Although that should be the norm—it’s not.

I wonder if it had been the norm decades prior, would Southwest Memphis have given the fossil fuel industry permission to move its polluting businesses to their community?

Credit Due

For decades, Southwest Memphis has carried a disproportionate pollution burden and now has helped the entire city dodge an additional risk to its water supply. But a verbal thank you—if Southwest Memphis receives one—won’t be enough for a community that remains over-polluted and one of the poorest ZIP codes in the city.

When the history of the fight is distilled, some will say aquifer advocates stopped the pipeline, some will say MCAP stopped it, others will say local elected officials did, and Plains will say COVID-19 stopped the pipeline.

But the ultimate credit must go to Boxtown and the other Southwest Memphis residents who were first to sound the alarm.

The Boxtown Neighborhood Association organized the first community meeting not hosted by Plains and community leaders invited elected officials to it; none showed up.

And it was Robinson, Jones and Pearson—daughters and son of Southwest Memphis—who carried the fight to a national stage during a pandemic.

It’s easy for the efforts of poor Black people and, in particular, Black women to be forgotten by history—or erased—to make more space for celebrities or people more palatable for white sensibilities.

But this example needs to be maintained accurately for generations to come. Because knowing about Southwest Memphis’ victory may be critical to how communities respond to the difficult environmental fights of the future.

Wells addressed this, too, in her 1892 book, “Southern Horrors.”

“The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press.”

This piece was published in cooperation with MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a nonprofit newsroom focused on poverty, power and policy in Memphis. Support independent journalism by making a tax-deductible donation today.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.