The Tennessee Valley Authority may have a big problem—and one that could soon spill over into Mississippi. The federally owned corporation manages the now-defunct Allen Fossil Plant in Memphis, Tenn., where environmental experts claim ash ponds have been contaminating groundwater said to be locally connected to the Memphis Sand Aquifer since at least 2017. This aquifer is the primary source of drinking water for the city of Memphis and serves other communities across the Mid-South.

To address the ongoing contamination of groundwater at the Allen plant, TVA proposed In October of 2020 that trucks transport all of the coal ash to offsite landfills: one in Memphis and another across the state line in Tunica, Miss. Following removal of the coal ash, TVA will backfill the ponds with “clean borrow material” such as soil taken from one of seven listed borrow sites near the Allen Fossil Plant.

TVA estimates that this process will take nine years and cost from $550,000,000 to $650,000,000.

Managers of the coal power plant, which closed in 2018, have historically disposed of 3.5 million cubic yards of residual waste, known as coal ash, by combining it with water in unlined ponds on the property. Coal ash is any of the various byproducts of burning coal to produce energy—fine particles of ash that fly up into smokestacks or larger pieces that collect at the bottom of furnaces. The waste product contains several chemicals hazardous to humans, but is controversially classified as “solid waste” by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Contamination at the Allen Plant in Memphis has prompted state agencies to investigate the antiquated operation. The Mississippi Free Press obtained documents indicating that the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation’s Bureau of Remediation is overseeing a remedial investigation, as well as an environmental investigation, which former TDEC Commissioner Bob Martineau ordered.

The Southern Environmental Law Center, on behalf of several activist groups, is calling for good-faith remediation efforts to combat the damage, but also claim that TVA’s proposed course of action may present other significant problems for citizens of both Tennessee and Mississippi.

‘Serious Environmental Justice Concerns’ for Tunica

Protect Our Aquifer, the Tennessee Chapter Sierra Club, Jobs with Justice of East Tennessee, and Interfaith Worker Justice of East Tennessee make up the coalition of groups concerned about TVA’s plan to remove coal ash from the Allen plant. The SELC letter written on their behalf cites TVA’s history of failures related to remediation efforts, especially the fallout from one of the worst environmental disasters in modern American history—the Kingston Fossil Plant coal ash slurry spill in Tennessee.

On Dec. 22, 2008, a TVA containment pond in Roane County, Tenn., failed and released more than a billion gallons of coal ash slurry into the surrounding area. Dozens of workers who helped clean the spill died, while hundreds more experienced illnesses they claim are related to coal-ash exposure. Several legal battles ensued as a result, some of which are ongoing.

Jim Kovarik, executive director of Protect Our Aquifer, spoke with the Mississippi Free Press about the demands outlined in the SELC letter. Kovarik and company want the safety guaranteed of those who will be responsible for removing and transporting the coal ash to Tunica.

“We don’t want several hundred people to walk away with coal-ash diseases or afflictions,” Kovarik said.

The coalition is also demanding the protection of people living in the areas where the coal-ash project will take place.

Tunica County—as well as the immediate area surrounding the south Shelby landfill—experiences high rates of poverty. In both areas, more than 80 percent of those citizens are Black.

The imposition of environmental racism on these communities is a major concern for critics of the coal-ash transfer. People of color have historically shouldered the burden of environmental crises in the United States in neighborhoods that are the most likely to be exploited. TVA was previously criticized for harming Black communities, but representatives from the corporation say the livelihood of Black citizens is a consideration they prioritize.

TVA’s Latrivia Welch told the Mississippi Free Press that the corporation has extensively engaged the public about proposed plans to remove coal ash from the Allen plant, speaking with neighborhood associations and holding virtual events to keep citizens informed during the pandemic. When this reporter asked about environmental-justice concerns, Welch asserted that TVA is dedicated to engaging the communities whose lives this project might disrupt.

“African Americans in the community being engaged is part of our consideration,” she said. “We live here. …This is home. … When we talk about impoverished people, you have to make sure that you are not impacting them unduly.”

Organizations who wrote the SELC letter do not agree that TVA is acting as a good steward of the communities the project will affect. “If ever there was a case of what’s called environmental injustice, this is it,” Kovarik told the Mississippi Free Press.

Boxtown vs. Byhalia Pipeline

The activist groups assert that the Tennessee Valley Authority’s plan to dispose of the coal ash is flawed and does not properly account for the people living in communities along the haul routes and where the coal ash will end up.

TVA’s plan to remove the coal ash and backfill the empty ponds means that heavy equipment will course through dense lower-middle class neighborhoods that are already strained by financial, social and infrastructural burdens.

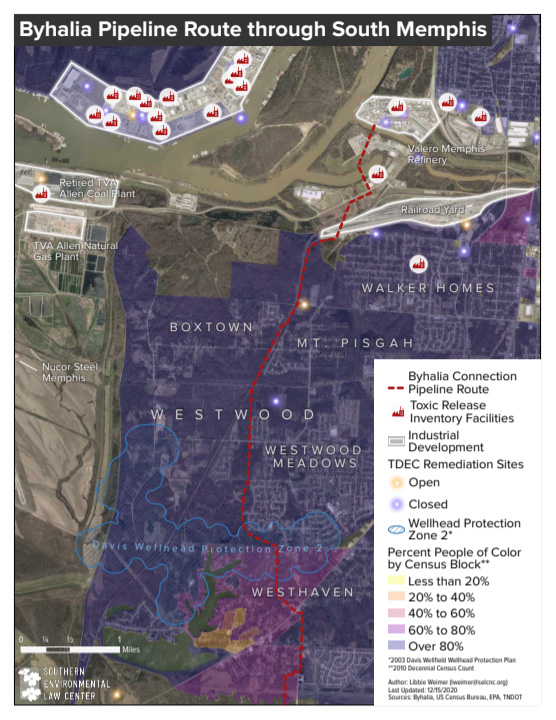

Citizens of one affected Tennessee neighborhood, Boxtown, are already fighting the placement of the controversial Byhalia pipeline in their community. The pipeline system, brought about by subsidiaries of Plains All American Pipeline and Valero, would carry oil from Memphis southeast to Marshall County, Miss., and is part of a larger effort to establish a system capable of transporting crude oil between Oklahoma and the Gulf Coast.

Critics are concerned that the companies are choosing communities for high-impact operations because the people in them may not push back in ways that wealthier communities might. “More affluent neighborhoods wouldn’t allow it, wouldn’t have it,” Kovarik said.

Leanna First-Arai of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a nonprofit news outlet in Memphis, reported that Wyatt Price, a supervising land agent for Plains All American Pipeline, told citizens at a Boxtown community meeting in 2020 how the path of the Byhalia pipeline was chosen.

“We took, basically, a point of least resistance,” Price told Boxtown residents.

The Allen Plant Problem

In its October 2020 proposal, TVA stated that a routine groundwater inspection near the East ash pond in 2017 revealed the presence of arsenic, lead, fluoride, and other unnamed toxins derived from coal ash in groundwater near one of two coal ash ponds on the property. Multiple sources told the Mississippi Free Press that McKellar Lake and the Memphis Sand Aquifer—the primary source of drinking water for Shelby County, Tenn.—have been “poisoned,” an assertion that TVA disputes.

“Based on the (remedial investigation),” TVA’s proposal states, “arsenic in groundwater was found in the upper portion of the Alluvial aquifer. The Memphis Sand aquifer has not been affected, and sample results meet USEPA drinking water standards. TVA plans to further investigate groundwater conditions beneath the [East Ash Pond] when safe to do so.”

The SELC letter states that TVA’s own data contradict the claims that contamination is limited to the shallow aquifer. Attorneys at SELC sought an independent review of TVA’s proposal and investigative reports by a chemical hydrogeologist, whose findings were attached and sent to TVA with the letter.

Dr. Douglas J. Cosler, of Adaptive Groundwater Solutions LLC, did not agree with the information TVA has provided.

“In the report that follows, I describe my independent review of the data collected and analyses performed pursuant to the (remedial investigation) and the related USGS-CAESER pumping test in the Memphis Sand. In particular, I evaluate the implications of the data for the risk of contamination of the Memphis Sand Aquifer by CCR constituents present in the MRVA aquifer at the Allen Plant,” Cosler wrote.

Citing Dr. Cosler’s reports on the information, SELC is alleging that the contamination at the Allen Plant is potentially worse than has been reported.

‘Profoundly Incorrect’ Assertions?

When the Mississippi Free Press spoke with TVA’s Cedric Adams—a chemical engineer who is managing the coal-ash removal project—he asserted confidence in the work TVA has done, but did not offer an argument concerning Cosler’s comments, which he confirmed he had seen.

“We feel we have conducted the science and the investigations to do what we need to do to improve the site,” Adams said.

“We have an extensive, robust monitoring program where we monitor the aquifer at three levels,” he added. “The shallow, intermediate and deep—we have characterized the upper alluvial aquifer pretty well, and we haven’t stopped.”

TVA claims that the contamination of the groundwater is limited to one area in a shallow portion of the Mississippi River Valley alluvial aquifer and two areas along the East ash pond. SELC, bolstered by Cosler’s findings and a USGS/CAESER report, wrote that test results indicate that the shallow aquifer where coal ash contaminants were found is hydraulically connected to the Memphis Sand Aquifer.

Cosler’s findings also suggest that water with coal-ash contaminants is already mixing with that contained in the aquifer so many in the Mid South rely on.

“Age dating of groundwater and elevated sulfate concentrations in Memphis-Sand Production Well 5 indicate that mixing of MRVA Aquifer groundwater with Memphis Sand Aquifer water is occurring in the vicinity of the Allen Plant and that potential ongoing transport of CCR constituents from the MRVA into the Memphis Sand Aquifer is occurring,” the hydrogeologist wrote.

The SELC letter goes on to criticize TVA’s efforts to analyze the contamination and characteristics of the situation. “The groundwater remediation approach outlined in the Proposed Plan, and the Groundwater Modeling Report upon which it is based, fail to account for these well-supported findings,” the letter states.

“TVA’s proposed remedial approach only scratches the surface of the likely groundwater contamination problem at the Allen site.”

A spokesman for the TVA indicated that an announcement regarding the project may come today.