“God is good. God is good,” Charles Chiu repeats, wiping the tears from his face with a balled-up tissue.

It is 2014, and Chiu, 83, has handed Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum Curator Emily Jones a photo of his father K.C. Lou and grandfather Charles J. Lou’s gravesites.

Jones recognizes K.C. Lou’s name, and then leads Charles Chiu and his family to another room in the museum in Cleveland, Miss.

There, she pulls down a brown box and takes out a Bible that belonged to K.C. Lou, Charles’ father. The Chiu family, who travelled all the way from California to Mississippi in search of the family’s full history, was getting much more than they initially expected.

“That’s my father’s Bible. Oh my God!” Charles Chiu exclaimed.

“In memorial of K. C. Lou, Pace, Miss. USA 1908-19 April 1946” is inscribed in red and black ink at the back of the Bible. The utter shock and joy at this new discovery is overwhelming, so much so that it brings Charles Chiu to tears. He has found a piece of the puzzle that is his father, a Chinese immigrant and grocery-store owner in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s. He died in 1946 at the age of 38.

〈MFP seeks to sustain the most diverse and inclusive statewide media outlet in Mississippi. Click HERE to Donate to our Truth-to-POWER Campaign!〉

“That scene where we found the Bible was a tearjerker, especially for my father,” producer Baldwin Chiu told the Mississippi Free Press in a phone interview. “And I thought I was taping it, (but) had an operator error on the camera. I did not capture any of the deep emotional periods. Maybe that was a good thing.”

His wife and director Larissa Lam said though her father-in-law was sobbing in the corner for five minutes, it didn’t make the film. She added that he needed that moment to himself and not for the world to see.

“You see him cry enough, but that was overwhelming,” she continued. “And what was beautiful about that was our daughter was only a little over 1 year old, and she ran up to Grandpa and hugged him. We don’t have that on camera, you know?

“It’s etched in our memories.”

‘Systemic Exclusion and Erasure’

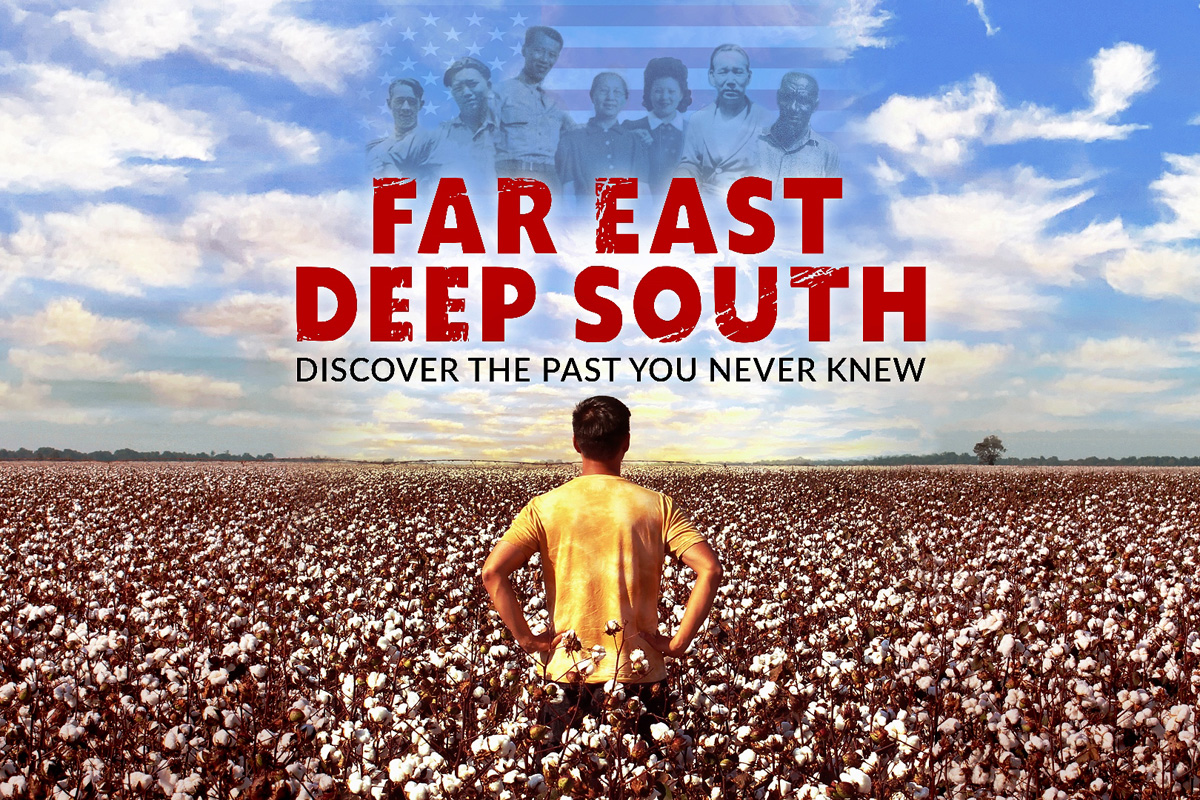

The film “Far East Deep South” follows Charles Chiu and his family’s journey from California to Mississippi in hopes of finding answers about his father K. C. Lou. When the family learned about the life of K.C. Lou and his contributions to the surrounding communities in Pace, Miss., just northwest of Cleveland in Bolivar County, they also discovered some harsh truths about life for Asian Americans living in the Deep South during Jim Crow.

For one, they learned the buried truth about the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law restricting Chinese immigration into the United States. The act prohibited Chinese men from entering the country as laborers with few exceptions for merchants, scholars and diplomats.

In 1920, when K.C. Lou was 17 years old, he and his mother, Shee Chin, entered the country through Angel Island in California, a U.S. immigration station that processed 1 million people. After 17 years, K.C. and his mother could finally be reunited with his father, Charles J. Lou, who had earlier settled in Pace, Miss., in Bolivar County northwest of Cleveland.

All the Chinese citizens had to register under the Chinese Exclusion Act and had to carry their registration papers at all times. Without said papers, they could face deportation and only the testimony of a white person could save them.

Although the The Page Act of 1875 put heavy restrictions on women coming into the U.S., Shee Chin had bound feet. Bound feet are a Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to change their shape or size. They were a sign that Chinese women were a part of the elite class, and it was also an effective way to get into the United States.

Before the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were no laws that mandated new arrivals be inspected at the port of entry.

Men who were not married had few options to settle with a woman in America due to anti-miscegenation laws. The laws against race-mixing—supposedly to preserve the superior white race—only gave men like K.C. Lou the options of returning to China and marrying there, then staying awhile and fathering a family, but ultimately returning to the U.S. to work. Thus, children grew up in China without fathers, which left a lasting impact for generations.

The Exclusion Act deeply affected Charles Chiu. It separated him and his father, K.C. Lou, severing any relationship they might have had. The last time he saw his father was when he was 1 year old; the encounter is immortalized in a photo and video reel. He lived in a Chinese village with his mother and siblings, while his father sent income back to China.

After the Civil War, Chinese men were recruited as laborers for Mississippi Delta plantations to fill a void after slaves were freed, leaving a predictable labor shortage and the desire for cheap workers to do the work. The book “Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi: The Twentieth Century,” produced by the Mississippi Humanities Council, explains that Delta planters joined in collectives to seek needed labor, including public relations and lobbying the U.S. government for help. One strategy was to recruit Italian and Chinese men as laborers. They believed Chinese workers, in particular, would work cheap and be resistant to malaria, the book explains.

After consortiums of planters met in conventions in Arkansas and Memphis, they devised a plan to send over two ships and recruiters to China to recruit workers, promising them lucrative work in “the Gold Mountain,” as they pitched plantation work in the U.S. The ships, the Ville De St. Lo and the Charles Auguste, arrived back in New Orleans with 400 Chinese immigrants, some of whom went up the Mississippi River to work on Delta plantations, as well as to Arkansas and Tennessee. Some, like the men of this family, landed in Bolivar County.

But the plantations’ transition from slavery to cheap labor did not go well for the Chinese, or for the Italians. Once the laborers realized they weren’t going to get the economic boost they were promised, they went into owning grocery stores.

The racist Chinese Exclusion Act came as a shock to Charles’ sons Edwin and Baldwin, who had never heard of the act until their visit to Mississippi in 2014. Lam, who is also Asian, said when it comes to Asian American history, they only hear about railroad workers, Japanese internment camps during World War II and maybe a vague line about the Chinese Exclusion Act. Most people cannot even name a prominent Asian American historical figure, she added.

“Whether it was intentional or not, there’s clearly a systemic exclusion and erasure of histories of people of color,” she stated.

“And even with the issue of Jim Crow and the application, we all learned that it was clearly targeted towards the African American community. Yet, it was applied to the Asian community, the Hispanic community, the native communities nationwide that we don’t learn about as well.”

This ignorance is one of the main reasons the couple made the film, she said, with the goal of influencing the education system that tends to exclude the full history of people of color. “We hope teachers (and) schools will start to incorporate this history into their curriculum to broaden how we teach American history so that we’re inclusive of other groups that have just been historically excluded,” the director said.

Baldwin added that they hope the film encourages people to become more sympathetic and empathetic towards other discriminatory history in this country.

“There’s a lot of Asian Americans that don’t really identify with the South. They don’t identify with the struggles that the Black community has gone through because they feel like they have their own struggles,” Baldwin said. “But in fact, we do have some similarities, and it should drive us closer together by understanding that we share some of the history.”

‘Neighborly Attitude’

Empathy and sympathy are especially needed today with the exacerbation of anti-Asian sentiment abound in the country. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism reports that anti-Asian hate crime reported to police in 15 of the largest cities and counties in the country rose from 169% in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the first quarter of 2020.

New York City takes the top spot with a 223% increase in hate crimes followed by Los Angeles with an 80% increase. The violence being perpetuated against Asian Americans started the “Stop Asian Hate” movement, which responded to a series of mass shootings at three spas and massage parlors in Atlanta, Ga. Robert Aaron Long, a white man, killed eight people, six of whom were Asian women.

Lam said the discrimination against the Asian community and other communities of color today seems to stem from a lack of knowledge and education that are part of the fabric of America.

But during the Jim Crow era, communities of color seemed to be more united than ever, particularly the African American and Asian American communities in the Mississippi Delta. “Far East Deep South” reveals the camaraderie and support these Mississippians had for each other as they deal with racism and discrimination during the Jim Crow era.

The “Second Mississippi Plan” launched Jim Crow with Mississippi legislators explicitly baked disenfranchising clauses and other racist language into the 1890 Constitution in order to keep freed slaves from voting and exercising rights supposedly gained after emancipation.

What is lesser known is that white Mississippians treated other people of color in much the same ways—as if they were inferior and deserved no rights of their own—even as many Black and Asian residents helped each other, the filmmakers point out.

“We don’t think we have a lot in common today and systematically, our communities have been pitted against each other,” she remarked. “This film shows that there was unity, that there was cooperation in terms of trying to survive together in an oppressive system that marginalized both communities, and there was the acknowledgement that there was mutual respect. Somehow, some of that has been lost in the generation.”

What’s missing, Lam believes, is that neighborly attitude that she found in the communities of Mississippi, despite the cloud of racism that looms over the state historically.

“At least in our interactions with the community in Mississippi and in other Delta towns, people know each other. They interact with each other. They say hi to each other. They generally care about each other,” Lam said. “And I think a lot of these attacks that you’re seeing today, too, are happening in a lot of major cities. And it’s because people are strangers, and they don’t know each other.”

Baldwin said the majority of Americans who do not have relationships with Asians or see them in their communities have a certain perception that they are perpetual foreigners with no history here and no suffering here, thus they’re not American. But that’s far from the truth.

“I think our film, our history and this country show the opposite,” he said. “This shows that we have been here for a long time. We have contributed, we have struggled together with multiple communities, and we need to acknowledge that we are Americans just as much as we may be ethnically Asian.”

‘Fully American and Fully Asian’

K. C. Lou stands on a boat beside a friend, laughing and smiling at the camera. And then he’s holding his infant son, Charles Chiu, and they’re surrounded by family and friends. This isn’t a photo, but raw footage in black and white of K.C. Lou. Throughout the film, he is an image stitched together through lively stories from neighbors and friends, photos and letters.

But K.C. became larger than life, becoming life itself, as the family sat and watched video footage that Charles’ grandmother, Shee Chin, gave him. In the film, Baldwin says the photo captured the last time his father, Charles, saw his dad, K.C. Lou, before he left China.

“When we first showed Baldwin’s dad watching the film, he didn’t know who the baby was that his father was carrying, and we’re like yelling at him: ‘It’s you! It’s you!” Lam said, laughing.

“Every time I see a section, I get so teary-eyed because of all the things that we were able to uncover. … To actually have the footage of his father holding his son. It was remarkable.”

“And to clarify, there was no audio,” Baldwin added. “You see pictures—OK, It’s a picture—but then with a moving picture, it’s like you’re experiencing that life. You can almost feel yourself being held by the grandfather.”

Since that fateful trip in 2014, Baldwin says it continues to be a bag of mixed emotions as he has watched his father reconciling with all that he has learned of his family history. For 70 years, he did not have a father in his life, and there were unanswered questions as to why, but now the veil has been lifted.

“Now at least he knows that he doesn’t have to blame his father for everything. He’s come to the conclusion that he was loved,” Baldwin said. “It was not by his father’s choice that they were separated, and there were all these laws in place. But, it doesn’t take away the fact that those years were missing.”

His father, Charles, is OK with people knowing his story with the hopes that other people will recall their own stories. He wants peace and unification between communities in this country, Baldwin said.

Growing up in Sacramento, California, Baldwin explained that he was always conflicted about his racial identity, flitting between whether he was American or Chinese. In the U.S., Americans would say he’s Chinese, not American, and when he visited China, he was told that he’s American and not Chinese.

Going on this journey and making this film was just as much of a transformative experience for him as it was for his father, he said. “I think a lot of Asian Americans are stuck in that place. Where do we fit in? Where do we belong? And I think after this, we can be fully American and fully, ethically Asian,” Baldwin said.

More than that, Baldwin finally has clarity to the mystery behind his father’s side of the family, history he can now share with his daughter.

“It doesn’t have to be so secretive. We have a lot more to talk to her about when we talk about our family and our family lineage. My daughter loves history now,” he said.

“She’s studied history from every ethnic group, and she’s only 7 years old. She makes her own collage of historical people in this country, and it’s beautiful to see how she looks at every color of face as an important part of American history.”

Lam said the experience was life-changing as she always found it peculiar that Baldwin didn’t know anything about his father’s side of the family. Even when they were sending out wedding invitations, there were no relatives on his dad’s side that he could send an invite to.

“I made a whole film to explain why we couldn’t invite anybody to the wedding from his dad’s side,” she joked.

‘If You Don’t Tell Your Story’

The month of May is Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, so “Far East Deep South” will premiere nationwide May 4 on PBS and run all month.

Lam said she and Baldwin have been making this film since their first trip in 2014, and audiences will see that the themes that run throughout it have been present all along.

“You hear some of the Chinese American Mississippi Deltans in our film talking about some of the bullying and some of the racism they faced,” she said. “For a lot of them, that was the first time I think they talked about it. Even though we spotlight some of the discrimination, we hope it can be a healing experience for people.”

The film was supposed to premiere last year, but the pandemic delayed their plans. However, Baldwin thinks it may have been a godsend, especially given the current climate.

“Maybe that was a blessing in disguise to where our film can now be available at a time, such as this, where it’s a little bit more important than it might’ve been 13 months ago,” he said.

Baldwin Chiu and Larissa Lam can be reached at their website, fareastdeepsouth.com, where they answer comments and questions. If people want to book them for speaking engagements or desire a private screening of the film, they can reach them through their website.

The married couple also hosts a podcast, Love, Discovery and Dim Sum, where they talk more about some of the hidden history they discover and issues of race and culture through an Asian American lens. “Far East Deep South” is available for educational license through New Day Films, Baldwin said.

“We’ve inspired a lot of people through our documentary to start digging into their own family history. If you don’t tell your story, no one else will, right?” Lam remarked.

“Far East Deep South” will premiere on the WORLD Channel documentary series America ReFramed on Tuesday, May 4 at 8 p.m. EST. It will also be available to stream on WORLDchannel.org, PBS.org and the PBS video app on May 4 and throughout the month for Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. The series will air on Mississippi PBS on Tuesday, June 15, at 8 p.m., and Wednesday,June 23, at 2 p.m.

Editor’s note: The above story has been updated with additional explanation of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.