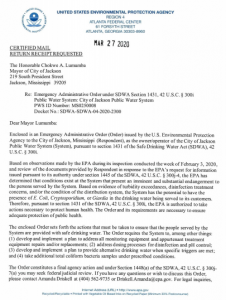

One year after an Environmental Protection Agency inspection visit catalogued numerous reporting, personnel and equipment deficiencies at Jackson’s water-treatment facilities, a pair of harsh winter storms kicked off the now-infamous water crisis, leading to a month without clean drinking water for many of the capital city’s residents.

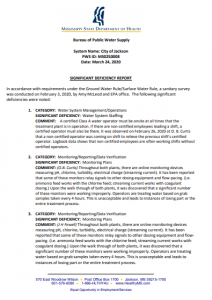

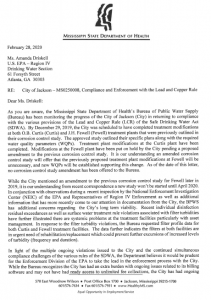

Following a heated debate between Jackson Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba and members of the Jackson City Council over allegations that the city withheld information related to the 2020 EPA visit, the Mississippi Free Press obtained a number of documents from the Mississippi State Department of Health describing these serious compliance issues at Jackson’s O.B. Curtis and J.H. Fewell Water Treatment Plant.

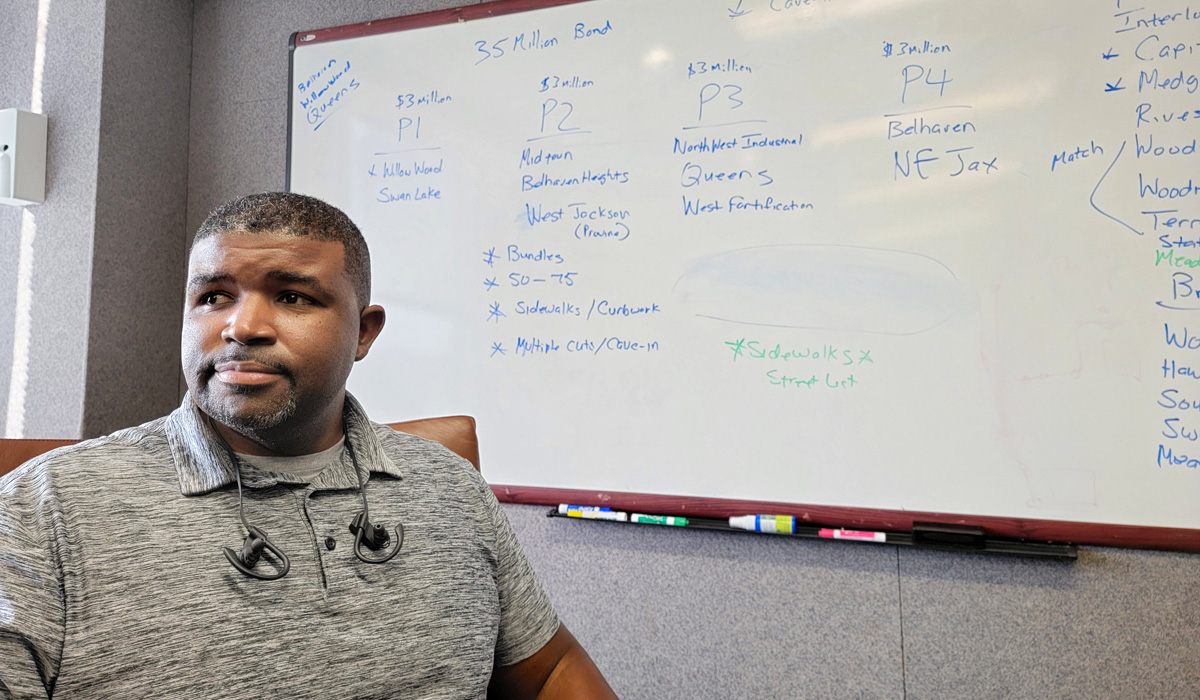

Jackson Public Works Director Dr. Charles Williams has been in charge of the city’s water system since last July, after the resignation of former Director Bob Miller. Miller held the position since 2017—Williams stepped up from interim director to full leadership of Public Works in October 2020.

The Mississippi Free Press met with Williams on May 3 to discuss the EPA’s emergency order, the ongoing effort to improve the city’s water treatment plants, the documentation of the city’s water treatment violations, and transparency over water quality and safety.

Nick Judin: One of the key issues that the Mississippi State Department of Health and the Environmental Protection Agency have identified at O.B. Curtis is a lack of qualified personnel. How many open staff positions were there at O.B. Curtis in February 2020, and how many of those positions have been filled since?

Charles Williams: We had vacancies for an instrument technician, electrician, lab supervisor, operation supervisor and some maintenance staff. Also, we are down approximately two or three licensed operators.

What concerned the health department was the instrument technician, which they felt we needed on staff to help with the calibration of a lot of the equipment that we use for our process. They were also concerned about the Class A operators that were at the plant.

(Since that time,) we lost a licensed operator, but we gained another one. We currently have three licensed water operators, and we need three more. However, we hired two non-licensed operators that should be able to take their certification tests this fall. We hired a lab supervisor recently—she started about a month ago. We still need to hire an instrument technician and an electrician.

The operations supervisor position is still not filled. That person needs to be a licensed operator. That position is normally the true lead in the plant. They set the schedule for the other operators. We need someone with quite a bit of experience in operations management. Normally, you would fill that position from your ranks, but currently none of our operators at the plant want that responsibility, so we have to look outside.

The position of instrument technician has been open for over three years, during which time some monitoring equipment was not repaired or calibrated. The EPA identified that some water treatment readings, including pH meters, were found to be erroneous in this time. For the years of 2017 to 2020, did the staff openings threaten the safety of water coming out of O.B. Curtis?

No. I think the focus on that was to help the City with the calibration of technical instruments required to keep the process in order. We recognize that—(instrument technician) is a very difficult position to fill, along with the Class A operators because of the pay.

I want to talk about pay, but first—when people read this EPA report, certainly laymen like myself, what we see is that an instrument technician is missing, and therefore some of the readings that the reports are based on are not accurate. Are there secondary measures that made sure that the water was safe during that time? Walk us through how O.B. Curtis prevented a compromise to the overall quality of the water.

Ideally, you would want to have a full staff. But in this case, I think it was more the responsibility of the lab supervisor to make sure that their reports are accurate in their readings.

There’s a log book that every operator has to write in. And there is data that you can obtain from our Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system. There’s also information that you can obtain from grab samples. The grab samples are used primarily by Water Operator I’s who are not licensed, but assist the Class A Operators in grabbing samples—routine through that particular operator’s shift. That grab data is compared to the information received off the SCADA system. It’s a redundant measure.

When you fill out the paperwork to turn in (to regulatory authorities), that data needs to be accurate. When that data is not there, obviously, if I was a regulatory (official) and I was looking at this data, then I would have no basis to say whether or not the water was safe.

It’s a check and a balance. As long as the finished water that comes out of the plan meets the requirements, it’s obviously a redundant measure for the city, but still, this goes back to the basic reporting. If there are some inaccuracies in the reporting, it’s going to raise red flags.

So when you look at the information that was provided to the EPA from around 2016 to 2019, and you see some inaccuracies in the reporting, obviously (regulators) should have some concerns about the quality of water.

Let me summarize to make sure I understand correctly. The instruments that were improperly calibrated due to the lack of an instrument technician were not the only measures testing if the water was safe, but secondary measures to confirm that the water was safe to regulatory observers.

Correct.

You mentioned grab sampling. The report concludes that the improperly calibrated devices include continuous turbidity monitoring equipment. Without that equipment functional, operators were forced to treat water at O.B. Curtis based on grab samples every four hours. My understanding is that this is a backup procedure that is only acceptable under current regulations for five days maximum. How long has O.B. Curtis used grab sampling, and has that problem been addressed?

We still use grab samples. That is a basis for redundant measures to make sure that your online instrumentation that is going through your SCADA system is accurate.

We just can’t rely on data from the SCADA system. You want to have a backup just in case something falls out of line in your computer system—a glitch or whatever. It’s very nice to have that grab data available in case you start getting some high readings and you want to back yourself up.

The grab data, for us, is always going to be a continual backup. We cannot rely just on the computer to tell us everything is accurate: you want to have something to back that up and make sure that everything is well within range of compliance.

Here again it sounds like these systems that we’re talking about are secondary, not primary. Walk me through the primary system that ensures that the water coming out of O.B. Curtis is clean.

That falls back on the lead operator at that time. He has the SCADA system in front of him. He monitors that—if something changes, he writes that in the log book. Every decision that that lead operator makes should be reflected in that log book. If there is an issue that is going on, it should be reflected in that log book.

From there, we also have sampling that is done continuously throughout that particular shift. That supports anything that we’re seeing on the SCADA system itself. If something is out of alignment, then obviously we want to check and make sure what is going on. There may be a turbidity meter that’s off. (Note: Turbidity is a key term in water treatment, meaning the cloudiness of the water, and is the primary warning sign of unclean or contaminated water.)

Often, we get out a spike in turbidity. It doesn’t mean that the water has high turbidity per se—but obviously we want to check it to make sure the turbidity meter is functioning correctly. We’ll go take a grab sample.

If there is a spike, and we’re getting high turbidity in the raw water that is coming in, then we would need to look at our treatment technique and make changes to ensure that we are treating the turbidity correctly before it goes to the next process. So there is a standard procedure that every operator should know.

However, we failed. I’m just being transparent with you. We did not properly document what was going on at the plant. If you don’t have proper documentation, you don’t have proper reports.

That leads to the conclusion that while you may not have been putting out bad water, the paper trail does not look good.

It does not look good in the sense that the results can’t be verified?

That is correct.

That log book—the information is from the samples. When you check your samples, all that information has to be reported correctly. If it is not reported correctly, it will lead to the conclusion that something went on.

The other issue is if we have an exceedance in turbidity. We are to notify the health department within 24 hours about that, about what caused it, why and how we treated it. If we do not, that is a technique violation.

We’ve had a number of those because we did not properly report when we had high turbidity. When you see the number of violations that we got when we had those exceedances, because we did not notify the health department, it leads to a level of mistrust.

Those failures to notify the health department—did they derive from technical error in instruments, or did they derive from human error in catching exceedances?

It doesn’t really matter. If there’s a spike that goes beyond the limit, we are to notify the health department within 24 hours.

How many turbidity spikes went unreported in 2020?

I don’t think we were that bad. I think we maybe had one or two occurrences at the most.

What has been done to address these missed reports since then?

We have addressed all the issues as it relates to the emergency administrative order. We’re in compliance.

One of the ways that we’ve been working very hard is to improve the accuracy of our reporting. That leads to training; we’ve done a lot more training with the operators. We hired a consultant from Cornerstone Engineering to assist us with that. We also have a former Mississippi Department of Health employee who is on that team, consistently meeting with our operators, going through standard operating procedures.

(Procedures like) how do we address a particular issue that comes up? How do we properly report it? We have seen the level of occurrences reduced, but there’s still a lot more work that needs to be done.

You told me last week, after the fire at O.B. Curtis, that some of the currently missing personnel would have been responsible for routine electrical maintenance. Describe these open positions, and expand on them as they potentially relate to the fire?

We had two high-service pumps—seven and eight—that were not in use, but still electrically tied to the system. We don’t (yet) know what the causes are. We don’t know if it’s something that became ungrounded. We won’t know until we pull the control panel out to thoroughly investigate what went on.

I don’t know if that could necessarily be tied to a lack of having an electrician on board. (Say) you have a house—you don’t have a licensed electrical contractor come every month to review your electrical components.

We don’t know if this was residual (damage) from the winter storm. The best thing for us to do is a thorough investigation. Because we don’t want this to occur again. It may be an opportunity to avert another issue like this. It could be something that’s tied to the wiring, it could be totally something different.

This was equipment that was powered, but not in use. So it’s not necessarily something that would have been worked with or inspected on a daily basis?

That’s correct.

One of the issues that the EPA found was that some of the ultraviolet light (U.V.) reactors were offline for significant periods of time at both O.B. Curtis and J.H. Fewell. Did that endanger the quality of water coming out of either plant?

The U.V. reactors are a critical part, right? They kill pathogens. They kill any waterborne diseases.

If none of them were in operation, yes, (the water would be unsafe.) But depending on the amount of flow that was coming in, we could still adequately treat the water with some offline. It just would take more time to do that.

I was not as thoroughly involved with the water at that particular time. So I can’t give you an accurate picture as I could now, because now we have our U.V. reactors working.

What I can say is that it would put a lot more stress on our operators. If four out of those six U.V. reactors were not properly working, that puts more strain on the others that are working. The water is still treated, but it limits the capacity of water coming out on your conventional side.

So, to your knowledge, when there were U.V. reactors that were not working, it does not mean that the water was not U.V. treated. Rather, it means that the water was treated at a smaller number of reactors—threatening the overall stability of the system, perhaps, but not outgoing water quality.

Right.

The EPA also detected improperly calibrated streaming current detectors, which help chemically treat the water.

Once again, that puts more stress on the operator because he has to judge the amount of chemicals in order to address the (differing) types of flows that may be coming in.

For instance, we have higher turbidity in the wintertime. The water changes. If we had the stream detectors working, they would help the operator gauge what’s coming into the plant and how to better treat it. So you wouldn’t put more chemicals in that could create sludge in your basins.

You have a better gauge—you can treat the water in a proper manner without having to guess as much, having to utilize your experience as much. And that’s what the EPA really wants to see us get away from.

They want us to (adopt) more automation. The streaming current detectors, the turbidity meters, all of these things. They want an instrument tech there to make sure they are fully calibrated all the time. So when water comes in, it matches the amount of chemicals to treat the water with.

All of these things flow in together. (It is) automation, full automation, taking a lot of the guesswork out that some operators would have to do.

It sounds like some of these missing systems in the process of treating the water automate the workflow, and some simplify it. Some of them are a matter of speed and capacity—like the U.V. reactors. Some are a matter of secondary verification of the fact that the water is being treated.

Correct. Procedurally, we were not where we needed to be. We had put a band-aid on O.B. Curtis for so long. We put a lot of stress on our staff and our operators to make do with what they had without making proper investments at the plant.

And as a result, for about three years, we just didn’t properly report (data).

There’s a minimum level (of performance), a medium level and a high level. Obviously, you want to be at the high level as far as efficiency and treatment processes go. But when you get to the minimum level, you’re still treating the water, and it meets compliance, but you’ve got a lot of red flags.

When you have some of your systems that are not properly functioning correctly, you’re not operating at that high level that you want to. And that’s where we’ve got to get out from: being at the minimum level. We have to start moving ourselves back up.

That’s what we’ve really been trying to focus on. When we got that emergency administrative order, we had just started turning some things around. We knew that we needed to move forward. That’s why we put in place the (State Revolving Fund) loan (from) 2016 that was just laying there. Nobody was doing anything with it.

We said, we’ve gotta take this money. We got to make the investments into the plant. The inspection and the report really validated some of the concerns that we already knew.

And now you’ve got a piece of paper that’s officially telling you that you need to step it up. You need to change the way that you’re treating water. You need to make the necessary investment and to ensure that you are meeting the safe drinking water compliance: that’s just the bottom line.

The EPA complained of membrane cleaning without the use of automatic monitoring equipment. They also said that O.B. Curtis lacks the ability to perform membrane integrity testing. Describe the purpose of these membranes, and has the problem been addressed?

There are six membrane trains and they help treat water. They are what we consider one of the newer technologies, as far as treatment goes. But they are very sensitive, high-maintenance pieces of equipment. And so we’ve already got two replaced. We got train number one that we’re working on right now. We just opened up bids for the replacement of train number five.

We’ve got four in production right now, but by August or September, I want to have all six trains ready to go. That gives us an instant 25 million gallons a day (MGD) of treated water.

We run membrane integrity tests every night, just to make sure that we meet compliance with turbidity, and that the trains are operating at the proper level, as far as the treatment process for water. If they don’t pass the integrity test, we take them out of service and then we get with (Suez Water Technologies) and we troubleshoot to find out what’s going on. Sometimes it’s, you know, a bad valve, an actuator, something minor.

But here’s the thing: failure to properly report that you ran the membrane integrity test is just as if you never ran the test (at all). So you can’t verify that that membrane was properly treating (cryptosporidium) and all those other requirements as it relates to water quality.

So when the EPA says O.B. Curtis lacked the ability to perform membrane integrity testing, it isn’t that the testing never occurred, but that the reporting of the testing was inadequate? Was that a staffing issue?

I think it was a combination of that, and also poor training. That’s something that we’ve worked on. We’ve made improvements in that (regard).

Part of it was that we said that we were running membrane integrity tests every night. Then that becomes part of our weekly and monthly reports to MSDH and the EPA. But at that time, I just don’t think that we were running the MITs (that often), and we were not properly reporting it.

So there were times that the membrane integrity was not being run.

I believe so. And once again, if you don’t have sufficient validation, you really can’t argue that case.

Suez says that you really can run them (less frequently), but I think, for MSDH and EPA, they would prefer that we run them every night to make sure that they are properly functioning and operating. And I think that benefits us, too, because if you have a good membrane integrity test, it means that everything’s properly running.

If you go a day or two and then you don’t pass the test, then that makes you wonder, well, what about those other two days? Did it just happen, or did it gradually happen over a number of days? So we don’t have a problem with (running the test nightly). I think that’s beneficial for both us and them.

The EPA found in 2020 that the City of Jackson had failed to perform filter maintenance at O.B. Curtis and J.H. Fewell. Does this filter maintenance include the raw water screens at O.B. Curtis that broke down this February and kicked off the system-wide collapse? Do any of MSDH and EPA findings relate to raw water screens or their cleaning system?

The raw water screens were replaced last year.

They just froze. I don’t think that had anything to do with it. We already had that project in the works. It just took a little time because we’ve only got two raw water screens. When you take one down, you put pressure on the other one.

It took a lot to get them replaced, but we did put new bar screens in and everything else (needed). So, no. The winter weather just shut them down because of the ice and the cold temperatures. There was no correlation between the two.

You’re saying that the screens didn’t freeze because of the automated cleaning system; they froze because of the weather.

Correct.

MSDH data for violations related to the water system really start to take off in 2020. We see one to three violations each year leading up to 2020, where it is suddenly 10 total. Here in March, in 2021, we’ve got six already. Are these the results of problems that have been building up until this point?

A lot of your technique violations that you’re seeing this year can be tied to the winter storm. We lost pressure, turbidity spiked. (When that happens,) we’re going to make some mistakes.

Bottom line, in 2020, we had to put out some technique violations back then, especially when the administrative order came in place. A lot that had to do with things that had already been done. But we still had to report that there was a treatment technique violation.

I feel that we are getting better, because we’re training, but we’re still going to have some missteps.

There’s still a human element to it. We still utilize human capital. We had one issue with an operator once, (for example), where he just dropped the ball. It happened. The water was not unsafe, but he just failed to report something that happened.

So these events happen. If you look at any water system, you’re going to have some (errors).

Many of the issues we’ve just discussed relate to existing personnel needs. Why is the City of Jackson unable to find the needed operators for its water treatment plants? Is the issue compensation? Why not pay these positions more competitively?

Let’s look at it from a holistic perspective.

I’ve spoken to a number of peers that are dealing with the same issue. Let’s just talk about public-works employees, period. Typically, they are undervalued and underpaid. They deal with infrastructure daily—maybe they have a GED or high school diploma. They have a skillset, but sometimes don’t have a college degree.

Incentive wise, who wants to go and shovel asphalt for $9 an hour? Even with a water-treatment facility, we’re still having the same issue.

Our plants in this nation are not getting younger. That’s for both water and wastewater. Most of the facilities were built 60, 70, 80 years ago. Talk to your typical politician and say “hey, let’s throw $50 million at building a new plant.”

No. Not going to happen. Translate that to now. I’ve talked to kids in high school, in junior high. I’ve gone over to a couple of schools and asked where we get our water from. “The faucet?” they say. OK. But how does it get to the faucet? There’s a silence.

You talk to students, even in college, and ask what career are you going into? (Do you) want to be a water operator? “What is that?” they ask. You say, it’s a person that basically runs a water-treatment facility. (The next question is) “Well, how much does it pay?”

About 30-something thousand dollars. “Yeah, right,” they respond.

So it’s a combination of lack of exposure to understanding water and wastewater, but also lack of improvement in compensation. (Previously), most people that we’ve been able to recruit are going to stay here, but the younger generation, they are a little bit different. They don’t want to wait five, 10 years.

They want to make $50, $60, $70,000 right out of college. Some of them make that much (out of) high school, you know? There are some jobs where you can make $14 or $15 an hour with a high-school degree. So that’s what we’re competing against.

Jackson has the largest surface water plant in the state. Well, your (hiring) pool is limited. So if we’re not able to recruit and retain the individuals that we need to run these plants, it gets depleted, which is kind of where we’re at now. We gotta start recruiting, we gotta get some folks in.

We have made some improvements. We have hired some water operators. They will eventually be able to take the test (to become Class A operators), but we have to keep the pipeline going, and I have to be able to keep them here.

So it’s very important that we look at a really sound recruitment and retention program to make sure that we always have operators available. That’s one thing I try to stress to the council.

We are in the business of making water. We don’t have an (operating and management) contractor to do that. The City of Jackson is solely responsible for operating those plants. So we have to make sure that we have the available personnel.

Let’s focus on compensation specifically. What does a basic water operator earn at O.B. Curtis, and why not raise that?

Right now we are in the low ($30,000) range. I have a recruitment and retention plan that we (intend) to present to the mayor. It’s going to increase the salaries about 20%.

So we’re looking at upping the salaries almost $6,000 to $7,000 from the lowest to the highest (paid employees).

So it would affect everyone?

It would affect everyone. For example, one of our lead operators, I think he makes roughly about $34,000. He’s been here about 15 years. He could easily go up to the low forties, $43,000, $44,000 based off of this plan. Hopefully that will be a good incentive for him to stay until he retires.

It will also allow us to have some other water operators come in and learn under him, so when he does decide to retire, we still have someone that’s capable of filling his position while he moves on.

In your conversations with the mayor, with city council, how have you explained this need for improved compensation?

That is something that we will have a very thorough discussion about in our budget this year. Unfortunately, I’m competing against myself. A lot of other staff members in the Department of Public Works need an increase, too. So do police officers, the fire department, all of these other departments.

They’re feeling the strain of not having adequate personnel because we’re competing with ourselves, but we’re also competing with (other municipalities). That makes it tough. We have to be sensitive. We’re not alone.

When I talk to some of my peers (in public works departments outside Jackson), the difference is that they can concentrate just on public works and engineering, because most of their treatment facilities are regional or shared.

They pay the money, and they don’t have to worry about it. In our case, we don’t have that luxury. We own and manage these assets. When you don’t have the revenues coming in to help stabilize the enterprise fund, you can’t make repairs at the plants, you can’t put money toward the distribution system. You can’t compensate your employees. You don’t have the money.

There has been a lot of friction between the City and the city council on the subject of the EPA emergency administrative order. Has the City met the reporting requirements from the order?

Yes. We have complied with that.

And the reporting?

Yes.

So why did the city council assert that it had not been informed?

I don’t know, because we brought it up a couple of times. I think that what they were really concerned about was the mayor not fully saying, “Hey, we got this emergency administrative order, and here’s what it outlines.”

That’s what they’re concerned about. But we referenced it during the winter storm—a lot of the deficiencies and how we came up with the $47 million (request) from that. I just don’t think the dots were ever connected. And I can’t go back, because I was not in this position.

In hindsight—I can’t speak for the mayor or (previous Public Works Director Bob Miller)—but I think they probably both would have done things a little bit differently. Obviously, COVID had just hit. We had a couple of meetings with the EPA during that time. It could have been handled a lot better.

So, legally speaking, you’re saying the reporting requirements were met. But in terms of the conversations that people would like to have about these things in retrospect …

I mean, that’s not an excuse. Again, I can’t speak for the mayor or Mr. Miller, but probably the City should have come out and said, “You know, amongst everything else we got going on, we got this emergency order from the EPA and here’s what it outlines.”

What we have done is we’ve taken the emergency order seriously. That’s how we got in compliance, you know? With the assistance of MSDH and EPA, with everybody working together, the City worked with them to get all of these items addressed as quickly as possible.

Is there anything that you, the Department of Public Works or the City of Jackson can do to better communicate these ongoing issues to the public? Can you go above and beyond what is legally required because of the severity of the ongoing problems?

Well, let’s just be honest. This was coming. If we look at it from a historical perspective, go back eight years—this was coming! Unfortunately it hit right when we had a pandemic going on. The focus now for the city, in my opinion, is what are you going to do now? We can sit here and talk about what you say you were told or not told.

That doesn’t negate the fact that we have got to put money in our water treatment facilities. We have got to improve staff, and we have got to put money in our water distribution system.

Last week, we had another minor water outage. To me, I think it shows the fragility of the system itself, right? So we don’t need to lose focus. Now the water is turned back on and the pressure is OK, we are still in a crisis. We’re going to be in a crisis until we can make the necessary repairs.

It’s not going to be done overnight, but it has to be consistent every day and each year. We have to make improvements. We need to be doing distribution projects. We need to be making upgrades at the plant. We need to continue to hire personnel. These things should be a continued effort moving forward.

I know we’ve got so many other issues that we have to focus on. We got bridges that are closed that need to be replaced. We’ve got streets that need to be resurfaced. We’ve got flooding that goes in areas around the city.

All of these affect the residents of Jackson. And this is the optimal time for the city to ask for resources and take those resources put into those areas where we’re deficient. We’re not going to be able to rebuild a city, we’re not going to be able to attract industry, and we’re not going to be able to serve our people if we cannot provide clean water.

Why take on this job—at Public Works, at the Water Department?

You know, the one thing I told my team is this: We know what we want to do. I’m not a politician. I leave the political stuff to the politicians. We’re engineers, we’re scientists. We are servants of the community. We already know that whatever we do, it’s not going to be right (to some people).

That’s fine. But we have a plan. We know how we need to address it. We’re going to focus on that. We’re going to have some setbacks. Did we want that fire on Friday? That was the last thing that we needed.

But it happened. And the way we responded was that nobody got down, nobody blamed anyone. We realized that Friday night going into Saturday morning was critical, that if we could get the water out at night, we’d start seeing our tanks refilled in the morning. We knew we were going to be in good shape. That was exactly what happened.

We took off from there. There’s always going to be issues at the plant. We want to make adjustments. We’re going to utilize whatever money that we get. We’re going to make the proper investments in the plant, and we’re going to move it forward.

When my time is up, I want to make sure that the foundation is laid. I may not build the structure, but I want to make sure that the foundation is proper, that whoever comes in and succeeds me, can take it and start building on that. Right now, our foundation is shaky, and we’ve got to stabilize it.

I think the only way to do that is to follow the plan. Sometimes it’s going to deviate a little bit, but if we just follow the plan, get the issues addressed at the plant, increase the personnel, make the improvements in the distribution system, we can get that going and keep it going. Then you’re going to start seeing the improvements in the system.

And that’s what people need to see. They need to see the improvements. They need to see the efforts and they need to have their confidence restored that when they turn on the faucet, the water is safe to drink, that it’s reliable. That’s our goal. And if we can’t do that? We’ll pack our bags and head on.

For more information, data and history regarding the ongoing Jackson water crisis, read Nick Judin’s “Under the Surface” series on Jackson’s water infrastructure, historic causes for its decay and potential solutions. Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here. Part 3 can be found here. Nick’s full and growing Jackson water crisis archive since March 1, 2021, is here.