Under the Surface

Part I • Part 2 • Part 3

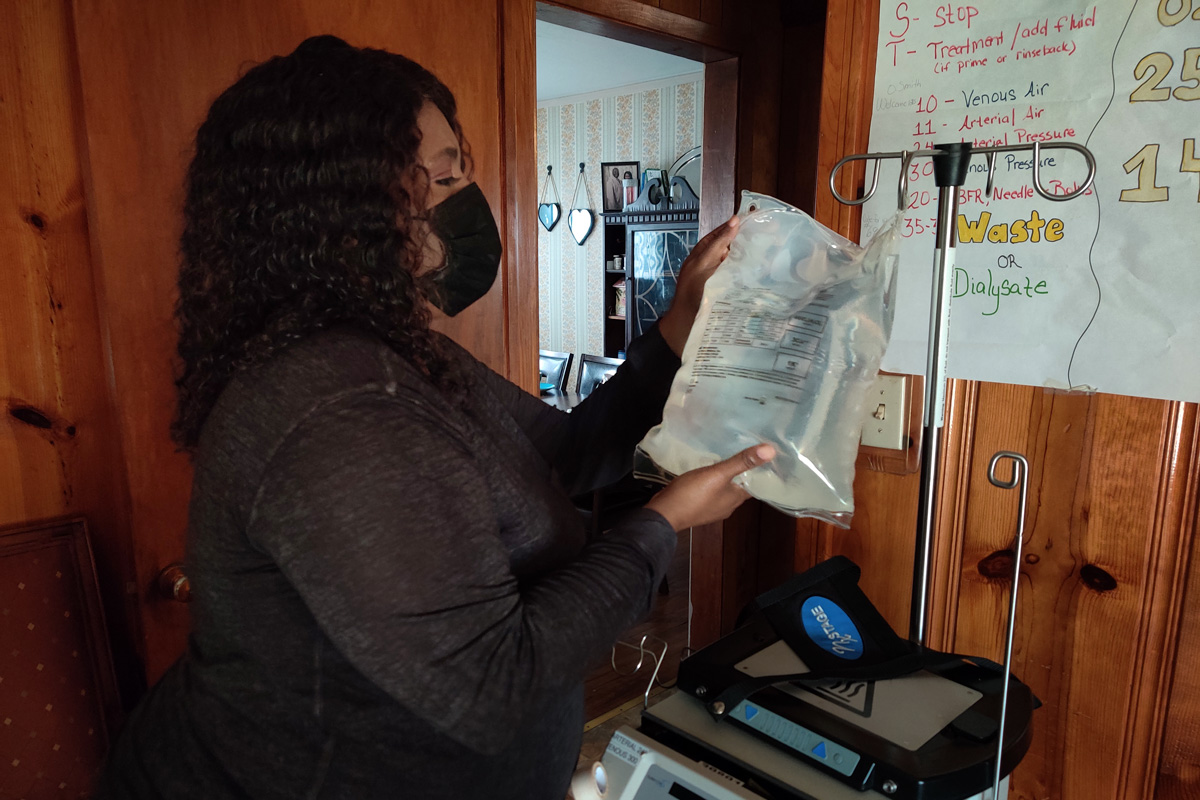

Tamiko Smith hooks the seventh bag of solution on a pole above the hemodialysis machine, with the first already warming on the heater. If the water is too cold, it could cause a sudden drop in her husband Otis’ temperature, triggering cramps, light-headedness or fainting. She is precise in the process, in her movements and the recounting of the procedure that keeps her love’s blood clean.

“We’ve never had this before,” she told the Mississippi Free Press later, in her living room in South Jackson. “Not to this extreme.”

She gestures to a stack of boxes piled high in her living room with sealed packages inside, like an I.V. supply for a giant. “My husband does dialysis four days a week. So that’s …” she pauses, counting the bags. “I have to have at least four boxes to be able to do that dialysis without using water. Normally we get two days’ supply, and now we’re stretched over to …” She waves off the thought and smiles beneath her mask. “I’ve lost count.”

Outside, the mid-February freeze is a memory. The deep frost robbed them of power, leaving all of Jackson buried under hard ice. The power blinked off, water trickled and tapered and finally dissipated. Those who could escape fled to hotels and the homes of families outside the city. Those who remained shivered under blankets until the power returned and then waited for the water to flow again. And waited, and waited.

What does it mean to be without water? It is innumerable small humiliations: the splash of a toilet flushed with a bucket, days on end without a shower, no clean clothes. It is weeks without a cooked meal, a sink full of unclean dishes, brushing one’s teeth with water from a bottle, if a bottle can be found.

For Tamiko, Otis and many others, it is something far more dangerous.

Otis rests in the chair by his hemodialysis machine, watching television. With safe running water, the process is simple: the machine filters and warms water straight from the pipes, mixing it into dialysate that filters his blood. Here in the long days of Jackson’s water crisis, it requires the continual, punctual delivery of premixed solution bags. Missing a delivery could mean severe danger. When the bag is warm, the process begins. It will be more than three hours before he can sleep, the better part of his evening.

Otis is a full-time EMT supervisor for American Medical Response. Tamiko, a receptionist at New Horizons Church as well as owner and licensed cosmetologist at Nu Dimension Hair Extensions, is pleased that he rarely rides the ambulance now, with all the stress and physical labor that entails. But he still works; the cancer that took his kidney could not take that from him.

Underneath the streets, Jackson’s heart is still frozen. Forty-three thousand veins shiver and contract in the cold, gasping for liquid. Each day, when it comes flooding through, the pipes will fissure and burst, 100 jagged breaks beneath the pavement in all. The month that follows brings catastrophe after catastrophe, with the pressure in the constricted lines erupting under the rush.

When Tamiko turns on her faucet, it whistles like a kettle. It is March 1st, the 14th day since the ice came, and Jackson still does not have water.

‘A Gap as Large as the Grand Canyon’

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has gotten used to the disaster press conference. After a solid year of floods, freezes, and pandemic orders, what once felt arresting now carries a queasy regularity. His task, as he stands in front of the railroad that borders downtown Jackson on March 9, is to touch on new urban development displayed on posters behind him, COVID-19 and, of course, the water crisis.

The freeze put a horrific new twist on the ongoing state of emergency over the pandemic. As temperatures plummeted, Jackson’s water-treatment plants could not take in the icy water. That left a webwork of pipes beneath the city cold and constricted for days. The situation deteriorated after a second freeze on Wednesday, a one-two punch that crippled the system. The grim task ahead would be refilling the buried pipes, many of which are decades beyond real effectiveness.

In the weeks that followed, the process of refilling the city’s transmission system led to more than 100 water-main breaks, as frozen pipes exploded with the pressure of the oncoming water. That left the capital city without water pressure, and even as the municipal workers continued the slow work of restoring pressure, the city could not guarantee the potability of the water until completing the repairs.

After the disaster press event, Lumumba speaks to the Mississippi Free Press directly, lamenting the halting, bitter communication between the City of Jackson and the State that followed the two freezes of Feb. 15 and 17.

“There is a gap as large as the Grand Canyon in terms of people’s perception of the work being done, often depending upon the demographic makeup of those communities …,” the mayor says. “The reality is the City of Jackson invests millions of dollars into our water infrastructure each and every year.”

Only a week earlier, Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann casually revealed to the Mississippi Free Press that there had been zero contact between himself, other legislative leaders, and either Gov. Tate Reeves or Mayor Lumumba to coordinate a response to the Jackson water crisis, though the catastrophe had just entered the third week by then.

During the exchange, Hosemann displayed an impatient disdain for the capital city’s leadership that many in the state found uncomfortably familiar when he complained that recent decades had brought little improvement. “You remember during Kane Ditto’s administration, he did repair work on water and sewer. So what happened since then?” Hosemann said.

John Kane Ditto was Jackson’s last white mayor; his successor, Harvey Johnson Jr., was its first Black mayor. At the heart of Hosemann’s critique was what he saw as a lack of meaningful plans, a concrete document for extracting the city from a worsening infrastructure crisis.

In fact, a master water plan had been completed in 1997, at the beginning of Johnson’s tenure. A new plan, the most current, came in 2013, at the end of his time in office. Between the two, the City of Jackson spent more than $200 million in water improvements alone, including construction of new storage tanks, water-treatment plant improvements, and transmission line repair and replacement.

Since then, an attempt to address the water system’s most surface challenge—customer billing—transformed from an ambitious deal with international tech conglomerate Siemens into a crushing failure. The installation of the new meters was such an irreparable disaster that, after an extended lawsuit, the company settled with the City of Jackson in early 2020, paying back the full price of the $90 million contract, about a third of which went to attorney’s fees. For Jackson, it was a victory that left the city close to where it started—save a decade of wasted time.

“I just want to be clear on this point,” Lumumba says in the interview. “There has never been a lack of a plan for the City of Jackson. Our problem has been that we haven’t had the funding to follow through with the plan we’ve already drawn up. A plan is only as good as its execution.”

In the weeks since the statement, Hosemann has labored against the disturbing implications of his dismissal in his remarks to the Mississippi Free Press, meeting with Mayor Lumumba for a deep conversation the latter described as both fruitful and respectful. House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, did likewise. As a result, the Legislature is now in possession of the hard plans that Hosemann demanded and a request to fund the capital city’s immediate water needs.

If cooperation prevails, Jackson will receive $47 million for critical work on its treatment plants and water distribution system, as well as a referendum for another 1 percent sales tax within the city to support the water improvements, estimated at between $13 million and $15 million in revenue a year.

Back at the presser, a gust of wind picks up. The posters behind Lumumba collapse inwards, pictures tumbling to the ground. Lumumba grabs one poster; the other knocks over a microphone stand.

“I couldn’t do both,” he admits, a tired chuckle following.

‘Welcome to Jackson, Mississippi’

Kehinde Gaynor recalls washing an apple. It is a small task, and yet it is first to come to mind when he reflects on the frustrations and indignities of a month without water.

“My daughter loves to eat fruit,” he tells me. “So she says, ‘Daddy, can I get an apple?’ But in my mind, I’m weighing that I have to wash this apple off with the same bottle of water that we’re using to brush our teeth, to drink, to clean.”

Gaynor lives in South Jackson with his wife, Nadia; two sons, Amari and Ayinde; and a daughter, Alora. He winces as he tallies up the expenses of food, water and cleanliness over the late winter freeze. Running water underpins virtually all of the comforts and necessities of modern life. Without it, normalcy is reserved for those with the privilege to pay.

For Gaynor, it was a staggering 18 days before water pressure returned to his home. He still has the tub of water he used for flushing and cleaning sitting on his back porch. A month out, the City is finally sending water samples to the Mississippi State Department of Health for testing. The citywide boil-water notice may be lifted on March 15, a month after the freeze first hit.

Outside, the wind whips against the side of Gaynor’s home, a choppy breeze on a warm day. Here, the deep freeze of less than a month prior feels like a vision of a distant era. Gaynor, who runs a multimedia company from his home, has water now, but it is not safe to drink. For weeks, he recalls watching national media overlook Jackson’s languishing crisis.

“My mom lives in New York, and she was looking at all the coverage of Texas—she only knows what’s happening in Mississippi because my brother and I were telling her,” Gaynor says.

He continued. “She said, ‘I keep seeing talk about Texas, but no one’s talking about Mississippi.’ I said yeah, they usually overlook us. She came down on me so hard! She said, ‘Well what are you gonna do?’ I was like, what do you mean what am I gonna do? This happens every year.”

After a stern dressing down from his mother, Gaynor shared his experiences in a video that quickly went viral, drawing the eyes of the nation closer to a catastrophe mostly overlooked in favor of the power crisis in nearby Texas.

The video follows Gaynor through the simple act of flushing his toilet, a task made infinitely more difficult during the long period without water pressure. “Imagine waking up thinking ‘It’s raining outside, I can probably capture some water to flush my toilets.’ Welcome to Jackson, Mississippi,” Gaynor says.

Outside his home, he has to laugh, admitting that the only reason he’d released the video was because of his mother’s urging. “That’s what mothers are for,” he says.

A Megaphone, Not a Whistle

Laurie Bertram Roberts, cofounder of the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund and executive director of the Yellowhammer Fund, has been coordinating and delivering direct aid to residents in need during the Jackson water crisis. Much of that aid is water, for drinking and basic necessities, but a population under the dual weight of a pandemic and water system collapse needs far more.

“Obviously, people need water—but when you’re already dealing with the pandemic,” Bertram Roberts tells the Mississippi Free Press, “a lot of people are not working, or their money is tight. People are already dealing with financial stress, right? Then this comes along and they’re trying to buy water. They’re having to use extra gas to go across town to go pick up (supplies), having to pay people to take them places to pick up water that’s non-potable so the toilets flush. Their needs are beyond just water.”

Bertram Roberts, who herself has struggled mightily with Jackson’s decaying water infrastructure, as detailed in a 2018 comic for Rewire, has done much for stranded residents in the aftermath of the freeze. But she is quick to highlight the gap between what her activism can do and what a present and responsible state is capable of doing and preventing.

“(This is) the role our governor refuses to play,” Bertram Roberts says. “It’s the capital city of Mississippi. What does it look like to have your capital city routinely not have drinkable water? It’s representative of a failed state. It’s not special treatment to make sure people have access to human rights.”

Gov. Reeves has been uniquely resistant to addressing or even acknowledging the severe crisis facing Mississippi’s capital city. In 2020, the governor vetoed a bill that would have allowed the City of Jackson to establish flexible payment plans to address overdue water bills in the city, many of which resulted from the faulty water meters installed under the Siemens contract. The bill passed in the House and Senate unanimously; only Reeves’ personal whim saw it die.

In his veto message, Reeves minimized the city’s infrastructure woes. “The City of Jackson is not the only municipality in the state with outstanding uncollected debt for water and sewer services … there are ‘disproportionately impoverished or needy’ Mississippians throughout the state that have overdue balances for water and sewer services.” That Jackson alone had recently emerged from the brutal fight with Siemens, an international corporation with a local office in Reeves’ home county of Rankin, over tens of millions of dollars and a decade of broken billing did not come up in the governor’s veto.

Reeves’ statewide guidance saw over half a million bottles of water and “several tankers of non-potable water” delivered to Jackson, but the coordination between the City and the State seen in the direct talks with Lumumba, Hosemann and Gunn has yet to materialize in the governor’s office. When asked in early March, Reeves replied that he had texted the mayor about the crisis. No communication followed.

“So when he says other municipalities in Mississippi have problems, how does that sound to people who are on the ground in Jackson, trying to solve these problems?” Bertram Roberts asks. “To me, it sounds like he’s saying that these other white cities are handling those problems on their own, while our Black leadership is incapable of handling the situation … It’s not even a dog whistle. It’s a yell through a megaphone,” she answers.

‘I Can’t Break Down’

Tamiko and Otis have been through it before. “We’ve had boil-water notices,” she says. “We were thinking it’s not gonna be long. We’ll be back.” But this time was different: weeks would pass before the shrill whistle of an empty faucet would yield to even a trickle of water. Even today their water is too unsafe for use in Otis’ hemodialysis.

Tamiko never had the hard conversations with her husband during the crisis about what to do if their supplies ran out. The crates of hanging bags arrived just in time for his regular home treatment, carefully rationed to dialysis patients in the area. Power was back, so they continued on as normal as normal gets in a year like this. Privately, anxiety gnawed at her.

“If you know anything about dialysis patients, this stuff is hard enough,” Tamiko explains. “A lot of dialysis patients are down sometimes, because they’re having to deal with this every day. You watch what they eat, what they drink. … They have their days.”

She does not look worn down by the experience, even though the experience must be wearying. “So I can’t break down. I can’t have a moment … I don’t want to discourage him, upset him. He has enough on him to try to do this every day,” she says.

Tamiko is even more concerned about the other dialysis patients in the area. Dialysis cleans toxins from the blood. It is not an elective procedure, and delays—or compromised treatment—can easily be fatal.

“My husband’s uncle lives in Clinton. He comes to Jackson for his dialysis. When this first started, he didn’t get dialysis for three days. You can’t do that. That’s life threatening,” Tamiko says. “Others in the area, she adds, waited even longer for treatment. Tamiko is neither old nor frail, but for those who are, even the act of lifting the pre-mixed bags might pose a challenge. The full scope of danger the ongoing crisis poses to the health and wellbeing of Jackson’s residents is impossible to quantify.

Tamiko is intimately aware of the underlying decay that limits the city’s ability to fix its water. At its peak, the city boasted over 200,000 residents. Now, it is estimated to contain roughly 160,000 people, with the lion’s share of that loss going to the surrounding bedroom communities.

Each day the city swells to around a quarter million as commuters living outside the city drive in for work, many for state government but without a commuter tax, payment in lieu of taxes or much support of any kind to make up for the resources they use and take home to other counties. That gap alone does much to explain the city’s current crisis. On a clear night, from St. Dominic’s overlooking Interstate 55, you can see the money traveling all the way back to Madison County.

Tamiko and Otis flowed in the opposite direction. She grew up in Rankin County, and together, they moved to Jackson, not out of it. “My family asked, ‘why are you doing that?’” The question didn’t faze her. “You know, everybody running out of Jackson doesn’t make Jackson better,” she says.

Many solutions remain to be explored. Jackson is still reeling from the catastrophic deal with Siemens to update the city’s water meters. Without accurate water billing, the enterprise fund that pays for improvements to water and sewer will grow thinner and thinner. Though Siemens surrendered $90 million in the settlement with the city for the shoddy contract last year, translating the $60 million after attorneys’ fees into the system it was intended to construct will not be easy.

The State of Mississippi can forge a different kind of relationship with its capital, one based on collaboration, rather than the recriminations, white flight and disinvestment of the 20th century’s end. But for that to happen, promising conversations, like the ones between Lumumba, Hosemann and Gunn will need to translate into material sources of support.

The federal government, too, plays a crucial role in the survival of the nation’s many municipalities. It was not so long ago that Environmental Protection Agency grants funded much of municipal water system improvement—without that support, many cities have crumbled from their mid-century peaks.

Otis is seated, and Tamiko is warming the solution for his dialysis. There is an odd symmetry between the danger to his system from a cold rush of blood and the devastation that icy water wrought on the cracked pipes beneath his home. Tamiko would never let him come to harm—but for the body of the city they inhabit together, no individual effort is enough.

This is Part 1 in Nick Judin’s “Under the Surface” series on Jackson’s water infrastructure, historic causes for its decay and potential solutions. Read Part 2 here. Nick’s full and growing Jackson water crisis archive since March 1, 2021, is here.