Under the Surface

Part I • Part 2 • Part 3

It was Wednesday, Feb. 17, 2021, when it all went wrong at the O.B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant. Dr. Charles Williams, public works director for the City of Jackson, could see the writing on the wall. “We started losing system pressure. Everything bottomed out. We had to figure out why,” he remembered in a long interview this week.

Plant operators scrambled to examine the mechanisms that take in and treat water to be released into the sprawling Jackson metro’s transmission system. But thick layers of ice and snow made physical examination of the outdoor plant’s machinery difficult or impossible.

That same bitter frost left many of the experts and vendors who could diagnose the situation stuck at home, subjected to a literal telephone game as they attempted to solve the spiraling catastrophe.

“It’s like a computer crashing. You’re trying to figure out exactly why it crashed,” Williams said. “It’s mechanical, it’s electrical. If the (system) isn’t operating, you can’t get water to the conventional side. And the conventional side was not responding.” The “conventional side” is the primary water treatment system, leading to a 10-million-gallon basin.

As the second frost blanketed the city of Jackson the same week, the crisis deepened. The basin that supplies the pumps leading to Jackson’s aging web of transmission pipes dwindled, revealing a thick layer of sludge from the reservoir. The pressure in the system declined catastrophically, underfilled water towers struggling to maintain pressure in the capital city’s most distant, elevated wards.

Even as the ice receded, and the entire team arrived at the water plant to assess the situation, the damage to the whole system had grown beyond the ability of the Public Works Department to immediately contain. “We met on site—we worked through different scenarios,” Williams said.

That Saturday meeting at O.B. Curtis was a revelatory one. “Everything started to unfold to us,” he explained. But it was too late, then. Across the city, chain reactions were erupting, the brittle system pushed beyond its limits, each point of failure compounding the next. The Jackson water crisis had begun.

‘Nobody Anticipated That’: Water Treatment Plants

The genesis of the crisis that left Jackson without drinkable water for an entire month is a living lesson in complex system collapse, siloed communication and the fog of war. “Put yourself in the moment,” Williams said. “We just got through one storm, and we had another storm coming in. Nobody anticipated that.”

He continued. “The way the plant works is that there are two 16-inch pipes that come in from an intake system at the reservoir. Water comes in from the conventional side, and water comes in from the membrane. If that goes down, you can’t bring water into the plant to treat it, or to discharge.”

The crisis as a whole was systemic, but the single greatest culprit was the raw water screen system, buried under ice and too clogged to process water at O.B. Curtis, the city’s primary water treatment plant, which was constructed in 1993 in Ridgeland, near the Ross Barnett Reservoir.

“The screens were replaced in the prior year, so the screens themselves were relatively new. We installed a spray wash system to keep mussels and other things that can accumulate on it off. But with the screens not operating, you can’t spray them,” Williams said.

With debris building up, liberating the entire system from swollen ice and then extracting the detritus that had poured in from the reservoir was no easy task.

The Mississippi Free Press asked Williams directly if raw water screen maintenance diverged from the norm prior to the winter storms. “To answer your question,” he replied, “the issue was not related to delayed maintenance.”

Unlike O.B. Curtis, the 107-year-old J.H. Fewell plant made it through the winter storm relatively unscathed, maintaining its current standard output of 15 million gallons per day (MGD).

Yet the continued operation of J.H. Fewell is itself evidence of a water distribution system in a continued state of arrested development. The plant, which is located near LeFleur’s Bluff park in Jackson, expanded to a max production of 58 MGD in the 1960s.

The tremendous decline in output is intentional. Both the 1997 and the 2013 plans call for a transition to O.B. Curtis providing all of the city’s water, a process that is dependent upon the eventual upgrading of O.B. Curtis to generate 100 MGD at maximum, more than the City of Jackson needs.

Former Jackson Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. explained to the Mississippi Free Press in an interview this month that part of his efforts to maintain the city’s struggling water system was to invest in the old water plant, in response to an EPA consent decree—a federal mandate to address over plant runoff into the Pearl River, one of the many environmental regulations that Jackson has fought to keep up with in decades past.

“J.H. Fewell was at the heart of the consent decree we struggled with,” Johnson said. “I opted to do the modifications to keep us from facing fines from (the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality). The modification worked, the discharge was discontinued.”

Currently, O.B. Curtis produces 50 MGD, though at the worst days of the crisis that plummeted to 20 MGD, the key factor in the system-wide depressurization.

Any real discussion of solutions to the freeze that crippled O.B. Curtis eventually arrives at a magical word: winterization. Winterization of municipal utilities is a constant concern in an era of radically shifting climate and renewed focus on crumbling infrastructure.

Williams promised an extensive investigation into winterization technologies was forthcoming, but cautioned that there are limitations on what the plant’s design would allow for. “Our plant was designed to be outside,” he said. “We’re not up north where a lot of those plants are enclosed.”

Modernizing the plant, making it more efficient and more responsive, includes winterization, Williams said. But it also helps limit the scope of danger that inevitable cold-weather malfunctions may cause in the future.

From the Iron Age: Water Distribution System

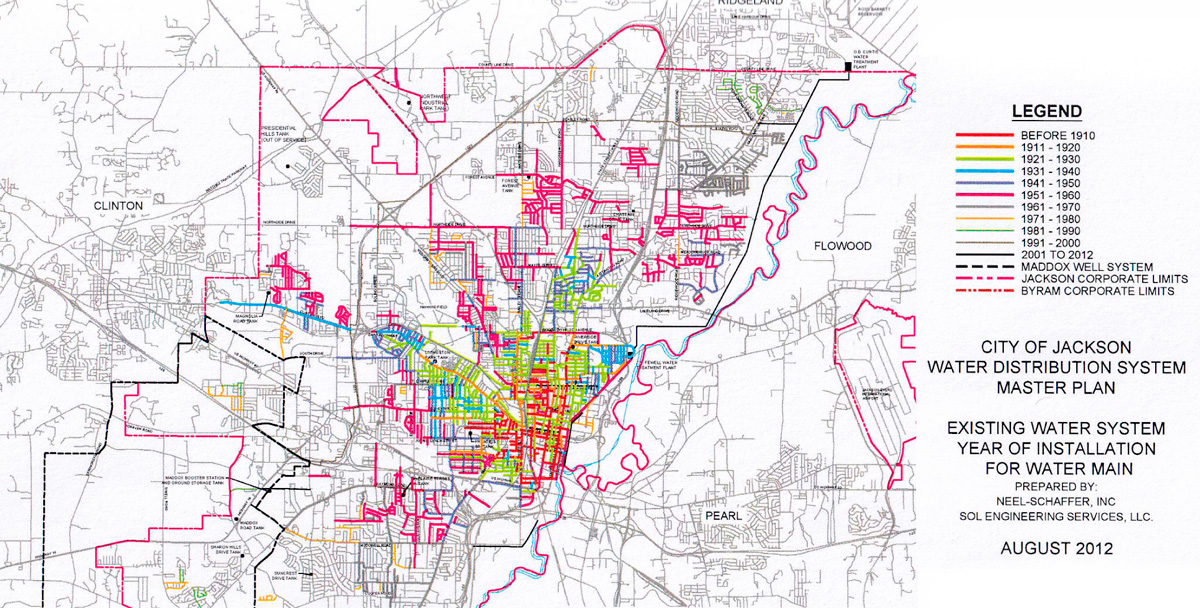

A plan exists for extricating the City of Jackson from its ever-worsening water crisis. Devised in 1997 and significantly updated in 2013, the Water Distribution System Rehabilitation Master Plan represents a collaborative effort between the city, Neel-Schaffer, a Jackson engineering firm, and a host of other civil engineering companies around the city.

The 2013 draft of the plan is extensive, covering every aspect of the city’s aging water system infrastructure, from the water plants themselves to the distribution system and the tanks that help maintain pressure in areas far from the pumps at O.B. Curtis and J.H. Fewell.

“The 2013 master plan is basically the playbook for us,” Williams said. “It’s really mapped out the system. The problem has been the implementation (of the plan) … We have not had the funding available to do some of those crucial improvements.”

The plan is unsparing in its depiction of Jackson’s ailing water system. “The distribution system has seen a continuing degradation since 1997,” it reads. “Unaccounted for water has increased from 19% in 1985 to 26% in 2012.”

The plan cites an American Water Works Association journal from 2012 that found Jackson’s pipeline repair needs are over nine times higher than the national average for similarly sized systems.

Williams reaffirmed the accuracy and continued usefulness of the 2013 plan, but said he couldn’t estimate how much those repair needs have changed since. “I will tell you this—we do have a high number of water main breaks that occur every year, and with that a high number of boil water notices. Any way you reduce that, we’re going to have to make investments in the distribution system,” Williams said.

The pipes that flow beneath the surface of Jackson are in dire shape because of their advanced age and utterly outmoded composition. “Discolored water complaints are prevalent, particularly in Downtown Jackson, where the oldest system piping is located,” the plan reads. “That piping is unlined cast iron that has exceeded its useful life.”

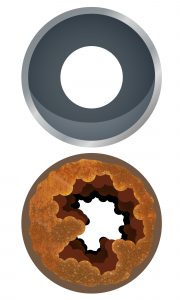

Unlined cast iron pipes have no place in a modern water distribution system. Their composition leads to tuberculation, a complex process of erosion that involves iron-oxidizing bacteria. An effective solution in the form of cement-lining has been available since 1922.

By 1939, standards for such linings had already been established, and yet the plan explains that pipelines installed before 1970 are “expected to be made primarily of cast iron … typically unlined, brittle, and a potential contributor to water quality problems to customers when system wide corrosion is present.”

As a result, the 2013 plans found that more than 112 miles of Jackson water pipes are still unlined cast iron—eroding pipe installed, in many cases, over a century ago. The Mississippi Free Press asked Williams if the 2013 map of Jackson’s pipes was still essentially accurate.

“Yes,” he confirmed, with one caveat. “They’ve just gotten older.”

Jackson’s water distribution map is a technicolor nightmare, with huge segments of the city’s core crisscrossed with pipes well over 100 years old. Generations of expansion pockmark the city streets, a roadmap of where Jackson’s urban core blossomed—and a record of where it now withers.

The plan is expectedly clinical in its assessment of these pipe segments, some of which have outlasted any human living during their installation. “Recent pipe coupons removed from the system have shown extensive build-up of rust by-products within the pipe exterior,” the plan reads.

Worse still, over 97 miles of water mains running beneath Jackson are less than 6 inches in diameter: the cause of over 40% of all water main breaks. These undersized pipes are simply not adequate for a modern utility system like Jackson’s. As days became weeks in the time since the February freeze, both unlined cast iron and undersized pipes alike shattered in the rapidly shifting pressure.

The danger posed by a hard freeze was well understood at the drafting of the 2013 plan. “The Ice Storm of 2010 highlighted the system’s vulnerability to widespread service disruptions,” it reads, in a warning rendered an artful understatement by last month’s outages. In the 2010 storm, hundreds of water mains burst, although service interruptions did not last for a full month.

If Jackson can acquire the funding needed for a full-scale renovation of its pipe system, the introduction of ductile iron piping, the current standard for water distribution, will eliminate the perennial bursting of water mains—estimated in the 2013 plan at up to five breaks per day—as well as the ruddy water many residents have grown accustomed to.

The total cost of the 20-year capital improvement plan, which includes upgrades to transmission, storage, water treatment, and most importantly pipe removal, was estimated to be $516,992,000 in 2012 dollars. Well over half of the entire cost is devoted solely to the removal of cast-iron pipes. Adjusted for 2021, that gives the 2013 plan in its entirety a price tag of just under $600 million.

Time, not just money, is a key concern for such a massive undertaking. “In order to spend $300 million on replacing pipes,” Mayor Johnson noted, “you’re talking (years and years) of scheduling to go about their installation in such a way that service would not be disrupted.”

Mississippi Rep. Ronnie Crudup Jr., D-Jackson, of South Jackson highlighted the importance of time in an earlier March interview. “It takes time to build these relationships between the city and the state. You build them, you finally get a plan together, and then all of a sudden, you get a new mayor, and it takes time to rebuild everything,” he said.

The 2013 capital improvement plan, as ambitious as it may seem, is only one significant step towards a modernized water system for the City of Jackson. “The overall CIP proposed in the Master Plan Update is extensive and expensive. However, it will still result in extensive portions of the distribution system with pipe lines over 50 years,” the plan reads.

Under Pressure: Elevated Storage Tanks

The City of Jackson has another pair of problems facing its water distribution system: elevation and distance. The hardest-hit areas of the city in South Jackson sit at some of the highest points the furthest away from the plants that provide them with water. These were the areas that spent weeks, not days, with barely a drop of running water.

In order to supply these areas and to provide additional pressure to the entire system, water towers dotting the city store millions of gallons of water, ostensibly to help in moments precisely like the February crisis.

But the water towers in the area were not full when the freeze hit. As Williams explained to Mississippi Today reporter Anna Wolfe, the towers are regularly drained as the system faces pressure loss.

This compounding burden on South Jackson led Ward 4 City Councilman De’Keither Stamps to push a $60-million request for the construction of four new water towers in the hardest hit areas through city council, which was later amended to $15 million.

“Byram needs a water tower, at least one. South Jackson needs at least two, and West Jackson needs at least one more water tower,” Stamps said to WJTV.

But with a staggering financial burden between the City of Jackson and a fully functioning water system, Dr. Williams acknowledged to the Mississippi Free Press that the construction of additional water towers was far down the list of realistic priorities for the city.

“Based on what we’ve seen, and from a historical perspective, we really need to put that money into improving our plants,” Williams said. “Second, we need to put that money in the distribution system. That is what would improve our reliability, as far as providing water,” he finished.

The folly in constructing additional water towers is relatively simple: something in the system is broken to begin with. “I don’t think (the towers) have ever been filled to capacity,” Williams said.

“That’s something we’ve been discussing for the past couple weeks. It’s been a big question mark. Why? It’s something in the distribution system.”

Addressing those greater systemic issues will be the focus of any money coming to Jackson from the federal or state level. “The science and the engineering tells me that we need to make improvements at our water treatment facilities and our distribution system,” Williams said.

Something that does appeal to Williams may help diagnose the larger problems with Jackson’s leaking, inefficient water system. “There is no current hydraulic model of the entire water system,” the 2013 plan reads. “Lack of a model prevents the City from determining adequacy of its water storage system to meet fire protection and peak flows. A model would provide an effective response on flushing when water quality complaints arise.”

In a statement to the Mississippi Free Press, Williams confirmed that the recommendation for a hydraulic model for the city has remained just that: a recommendation. “It has been discussed in the past,” Williams wrote. “No formal action or funding has been authorized to implement (it).” But it could help the city move forward. “It would help us understand the complexity of the water distribution system, and how to make it more efficient and reliable,” he finished.

A Draining System: Staffing

If the three major elements of Jackson’s water system—plants, pipes and towers—are its key organs, what remains to be understood is its connective tissue: the work force that keeps the system moving.

As physical access to O.B. Curtis itself was an instigating factor in the February crisis, the Mississippi Free Press asked Dr. Williams if part of the plant’s winterization improvements might be an investment in transportation for employees in severe weather conditions.

Williams’ response was telling. “We didn’t have an issue with getting our people there,” he said. “What I can’t tell you is how a particular vendor would make improvements in how they respond. The problem is not just public works department employees. The problem is also private vendors and contractors who help maintain the system.” The city has less direct control over the operating procedures of these vendors.

His answer intersects with another open question in any complete examination of Jackson’s water problems: a contraction in available professionals. “I think it’s something you see in the industry itself,” Williams said. “I mean, you don’t have a lot of people that have gone into the water industry that probably did 20 or 30 years ago.”

The trend, Williams says, is a national one, as stagnant pay lures workers out of public service and into private industry. Mississippi suffers from this problem in a dramatic and multilayered way.

Dr. Jim Hood, assistant commissioner for strategic research at Mississippi Public Universities, estimated in a March 24 presentation that Mississippi loses two out of every three engineering graduates to other states within five years of graduation. The compounding forces pulling fresh talent towards private industry and out of the state has left the city’s Public Works Department understaffed, on top of being underfunded.

“I’m hoping that as (the federal government) continues to enforce more regulatory requirements,” Williams said, “they will also put more of an emphasis on assisting municipalities with having trained personnel at their treatment facilities.”

“Dr. Williams is right,” Harvey Johnson said. “I think we saw that. I was in office for 12 years, and I saw young, promising engineers come and go.” The former Jackson mayor recalled numerous instances of fresh talent joining the city’s Public Works Department for mentorship and licensing purposes, only to depart for private industry—or other states entirely—once they’d achieved independence.

Johnson didn’t blame the young professionals. “There’s a corresponding opportunity for them to go and work in the private sector and make more money,” he said. And other states promised the opportunity to work on bold new projects. “There are limited opportunities for them to use their craft here, because we’re just not doing a lot of building,” he said.

Though he acknowledged the structural problems facing the city’s civil workforce, Williams was defensive of his team, insisting that mechanical failures from years of decay, not individual human error, was to blame for the crisis. “If we were fully staffed, would it have minimized the impact of the winter storm? No,” he said, resolutely.

Still, time marches on. And though the public works director believes his department did the best that they could given the circumstances of the system and the storms, the fact remains that staffing issues will only complicate the road ahead.

“Do we need additional staff—class A operators? Yes. Do we need additional maintenance staff? Yes. I’ve been vocal about that. That’s not anything that’s being pushed under the rug,” Williams said.

The February frost has abated. O.B. Curtis pumps out its expected 50 million gallons a day. If a sense of normalcy pervades, it is only a passing sensation, a surface-level calm. The water treatment plants are no more prepared for a deep freeze than they were on Feb. 14. Beneath the city, hundreds of miles of ancient pipes grow more ancient with every passing day.

The towers drain, the system leaks, and the people wait to see what comes first: a solution, or the next storm.

This is Part 2 in Nick Judin’s “Under the Surface” series on Jackson’s water infrastructure, historic causes for its decay and potential solutions. Part 1 can be found here or you can continue to Part 3 here. Nick’s full and growing Jackson water crisis archive since March 1, 2021, is here.