Peering over a hedge across from her family’s home in Natchez, Miss., 5-year-old Jes Simmons, as she is known now, watched in curiosity as a young blonde girl simply existed. Jes didn’t have a “crush” on the girl, but the femininity that bloomed across the hedge fascinated her. This state of being, so different from her own, perfectly aligned with the feelings in her heart despite the fact that she was assigned male at birth.

Born in Farnborough, in Kent, England, in 1954 as Joseph Edgar Simmons III, Jes Simmons’ relationship with her transness growing up was not only indescribable to her personally, but also to the rest of her world. Christine Jorgensen, the United States’ first widely known openly trans person, had only recently come into the public eye in 1952, and the words transgender and gender dysphoria were hardly the mots du jour they are now.

Around age 9 while in her father Edgar Simmons’ study—he was a Mississippi poet—Simmons picked up a pile of discarded poems and began to draw. After drawing her hand and an arm, she adorned her sketched body with rings and bracelets and placed the words “emeralds,” “rubies” and “diamonds” around the paper.

Years later when Simmons found this drawing in a 1950s Columbia Encyclopedia that her mother, Kathleen Floyd Simmons, used to collect her and her brother’s drawings, she was astounded by how much this childhood drawing communicated about her internally.

“Even at that young age, although I didn’t have any words to explain what was going on inside, a picture like that speaks volumes,” Simmons says now in an interview from her home in Farmville, Va. “Admittedly, I don’t think my parents looked at that drawing and said, ‘Son, why are you putting bracelets all over your arms,’ but it was my way of communicating.”

Her parents never pressed on the gender fluidity of her self-expression when she was a young child or how she dripped with androgyny during her teen years. Still, despite finding ways to express her gender dysphoria through drawings, or dressing up as a witch with a “female mask,” Simmons says her life up until her transition was “solitary.”

She is clear, though, that her life before transition was “not lonely, but solitary” with a tone that implies acceptance, but not sadness.

In interviews, Simmons shows an unusual balance of intelligence and relatability, and an honest interest in who I am. She has an unexpected respect for the “Twilight” novel series, which stems from her own well-articulated theory about the intersection between transgender people and vampires. (She insists that Bella Swan is “one of the most important female characters in literary history.”)

Simmons is a spectacular drummer, a skill she inherited from her father and one she passed down to her daughter, and there is a moderate melody in her tone.

What is most obvious about Jes Simmons when we speak is how almost unnervingly calm she is because she has nothing to hide. Jes is Jes, and she knows that.

‘People Innately Know They’re Trans’

You can tell by the way that Simmons, now 65 and retired from administration and teaching English at Longwood University, discusses herself and who and what she cares about that people with creativity in their roots raised her. Her poet father and English dancer mother met in England when a “writer friend” of Simmons’ father invited him to come visit and meet the dance troupe where her mother was a principal dancer and actor.

The foundation of her parents’ meeting, such as its purposeful happenstance and the fusion of people from two relatively different cultures, would serve as a precursor to the chance and bisected gender distinctions that would pattern Simmons’ life.

Simmons recounts a story claiming that as a child she glided to the living room and “grandly announced” that she was going to “have a bath, y’all” pronouncing bath like “bawth” with a British levity and “y’all” with a drawl. “That combination of London and Natchez is astounding, and maybe the dysphoria within my language at that moment was even reflective of my gender dysphoria,” Simmons says.

Elaborately, the former university English professor uses a metaphor to describe gender dysphoria.

“It’s like handedness,” she begins. “When you’re born, no one puts an R or an L on your right hand or your right hand. You just know, and it even feels weird to write with your other hand. If you’re right-handed, even trying to put your left arm over your right when you cross your arms is physically awkward.

“So it’s a felt sense. I know I’m right-handed and that I’m not a male,” she concludes.

Simmons’ roots as a writer then creeps in. “I don’t think a lot of people understand what it’s like to be called to be a writer just like they don’t understand that people innately know they’re trans,” she says. “You can take classes in creative writing, but unless you have a sure sense that you’re a writer, you’ll never be able to listen to the calling to write, which is like the calling towards the female that I had.”

During her childhood, Simmons moved around due to her father’s occupation, living in New York, Virginia, Illinois and Texas before returning to Mississippi and finishing high school in Jackson at Provine High School. It was in El Paso, Texas, though, that a turning point in Simmons’ self-discovery occurred when Simmons’ father offered her $5 to read Carl J. Jung’s “Man and His Symbols.”

“At first I was reading it for the money, but then I came across the term ‘anima’ or the female inside the male,’” Simmons says.

“Man and His Symbols” describes the anima as “the personification of all feminine psychological tendencies in a man’s psyche, such as vague feelings and moods, prophetic hunches, receptiveness to the irrational, capacity for personal love, feeling for nature and his relation to the unconscious.”

Simmons said Jung’s content was not entirely clear to her in the seventh grade, but that it made palpable the tension between who she presented as and who she was. “I remember clearly thinking like a bell went off and saying, ‘Oh, that’s who she is,’ and by she I meant the person that was with me but not male,” Simmons said. “That word (anima) gave me some relief.”

Unlike today where libraries have LGBTQ sections, and a Google search of transgender yields 150,000,000 results, Simmons said the late ‘60s and early ‘70s were bereft of LGBTQ literature and general knowledge outside of the hetero-normative world. That deficit caused her to grasp for straws while searching for the vernacular associated with her identity.

“You could not find LGBTQ books anywhere so there was really no recourse but to drift in this state of not knowing what’s what other than an internal self-sense of being female,” said Simmons. “Back then there was no internet, and you really trusted gaydar to find people who were LGBTQ.”

When Darden Wade, Simmons’ best friend from high school, begins to tell me about the beginning of their friendship, he talks about her with all the freshness of someone he just met yesterday, but with the sincerity that comes naturally from their 40-year relationship and side laughter indicating marvelous inside jokes between them.

Wade says the tension in Mississippi’s public schools from recent integration decisions in the early 1970s kept their conversations far from gender identity.

“As high school kids, now in addition to dealing with the usual pieces of classes, we now had to deal with the tension rising about court-ordered desegregation, so we didn’t think much about sexuality or preferences,” Wade said. “Girls were girls.”

Whether or not it was obvious to Wade, Simmons’ gender identity was at the forefront of her mind. The two possible instances of Simmons’ gender dysphoria that Wade noticed were “very brief,” he said.

The first was on a day when Simmons and Wade were taking a break from making “the dumbest” silent movies, and a gaggle of girls walked by. Wade said Simmons struck up a conversation about the girls’ dresses.

“I can’t remember the particulars of the conversation, but I do remember thinking, ‘Wow, this is a topic we don’t talk about much,’” Wade says.

The second was when Wade became involved with theater and “Jes became infatuated” with an actress in his show, as he puts it. “Looking back, maybe that was a sign to her and to me, but if that was a sign, the question then is how do you bring that up?” he says.

Soon, while Simmons was studying at Millsaps College in Jackson in 1974, American entertainer Canary Conn published her memoir, “Canary: The Story of a Transsexual,” providing Simmons with a haven and a story that spoke to her acutely. The book’s 11-word tagline, “trapped in a man’s body he should have been born female,” was simple but articulated all of the complexities of her internal strain.

While at a local Jackson bookstore dressed in a blue turtleneck and jeans with “longish hair,” Simmons held Conn’s memoir and was hit with a wave of connection. “I remember feeling an out-of-body experience like, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s something here for me,’” Simmons says.

While Simmons held the book, another customer entered and asked the owner to point out the psychology section. The owner pointed toward Simmons, and the customer said, “I see it, next to where that young woman in the blue turtleneck is standing.”

Millsaps, Marriage and Self-Segregation

While pursuing her B.A. in English at Millsaps between from 1972 to 1976 Simmons was “extremely gender dysphoric.”

“I was severely struggling psychologically and emotionally,” she says blithely. “I was attracted to young women in my classes, but I didn’t know if I wanted to date them or wear their clothes.”

In between classes at Millsaps, Simmons would sit in her car and avoid the student union. This self-segregation was not out of fear of other students or disdain, but because she was trying to “understand” who she was.

“I mean, I was friendly with them in classes, but I never even dated. In fact, the first woman I dated was at Mississippi College, and I ended up marrying her,” Simmons says.

After receiving her B.A. at Millsaps and then her M.A. at Mississippi College, where Simmons’ father had previously taught in the early ‘60s, Simmons married her now ex-wife and taught at Texas A&M while completing her PhD.

Simmons and her wife had open lines of communication about her gender dysphoria, with a slight hope that marriage would mitigate her gender-dysphoric turmoil.

“We hoped that marriage would maybe help alleviate the anxiety and concerns,” Simmons says. “And for a while it did, but it never goes away. I still love her and have not a single negative thought about her.”

Once, while at a marriage-counseling session, the counselor asked Simmons’ wife what had initially attracted her to Jes, and she answered, “He’s unlike any man I ever met.”

Simmons chooses not to name her wife, but not out of fear or shame, but in a manner that translates as respect and love.

‘Not Many People Have a Lesbian Dad’

In 1986 the couple had a baby girl, Laura Simmons, while they lived in Texas. “Because not many people have a lesbian dad,” Simmons, a lesbian herself, says they assume her upbringing was distorted or vastly different from their own.

But the younger Simmons’ reflection on her childhood is far from the laborious tale that I, admittedly, expected.

“My dad’s always been my dad,” Laura Simmons says. The elder Simmons’ transition came when Laura was only 11, so for the majority of her life she’s known her dad as Jes.

“When my dad told me that she wanted to become a woman, I can just remember thinking, ‘will it make you cry less and make you happier?’ She said yes, so I said, ‘OK then, well let’s do that,’” Laura Simmons says.

The unconditional acceptance of her father that Laura Simmons expresses perfectly aligns with the profound consideration Laura has had since a young age as Simmons describes it.

“One day I was talking to my daughter, and I said, ‘I hope this doesn’t make you lose friends at school or anything like that,’ and she said ‘Dad, if I lose friends because of this they were never my friends,’” Simmons says. “And she was only 11, so I was taken aback.”

Laura Simmons says the concept of her father’s gender identity never prodded at her or made her mind wander. She was most concerned about the intense depression and discomfort that she watched torture her father.

“I was more worried about my dad and wanting to make sure she was happy and safe,” Laura says. “There weren’t a lot of people checking in on her, and so I wanted to do that because I was a kid. That was my dad, and as a kid you don’t want anybody in your family to hurt.”

In a mini-documentary made in 2018 titled “The Jes Simmons Story,” Simmons says before her surgical transition and the dissolution of her marriage, her mind offered her two options: surgery or suicide. In a 2015 profile of Simmons, she said at age 8 she would count down nightly and pray for God to kill her.

“I didn’t realize not everyone had those thoughts, but my gender dysphoria had to have been that intense,” Simmons says. “Even at that young age it must have been such a confusion roiling inside me and causing all of that turmoil.”

Those thoughts never fully left Jes’ mind, and she struggled with the stifling of her identity for years before she fully stepped into her authenticity as a woman.

In 1989, Simmons and her wife moved to northwestern Ohio both for Simmons to take an assistant-professor position at a private university, and to raise Laura there, which she calls a “great place to have a family.” There, though, transphobia cost Simmons her teaching career when she announced her intentions to transition.

“Having a transitioning teacher was not heard of at all, so they ended up giving me a year’s severance,” Simmons said. Previously, she had moved up from assistant professor to an esteemed position as division chair for the university’s humanities department.

“You have to be well-liked and respected to move up like that, and I was, but the transition was not something they were ready for,” Simmons says. “And even though I was tenured, there was no law against them dismissing me.”

The momentous June 15, 2020, Supreme Court decision that upheld protections for the jobs of gay and transgender Americans would have seemed preposterous to Americans living in the 1990s with the recently passed the Defense of Marriage Act (which included a rejection of prohibiting employment discrimination in the private sector).

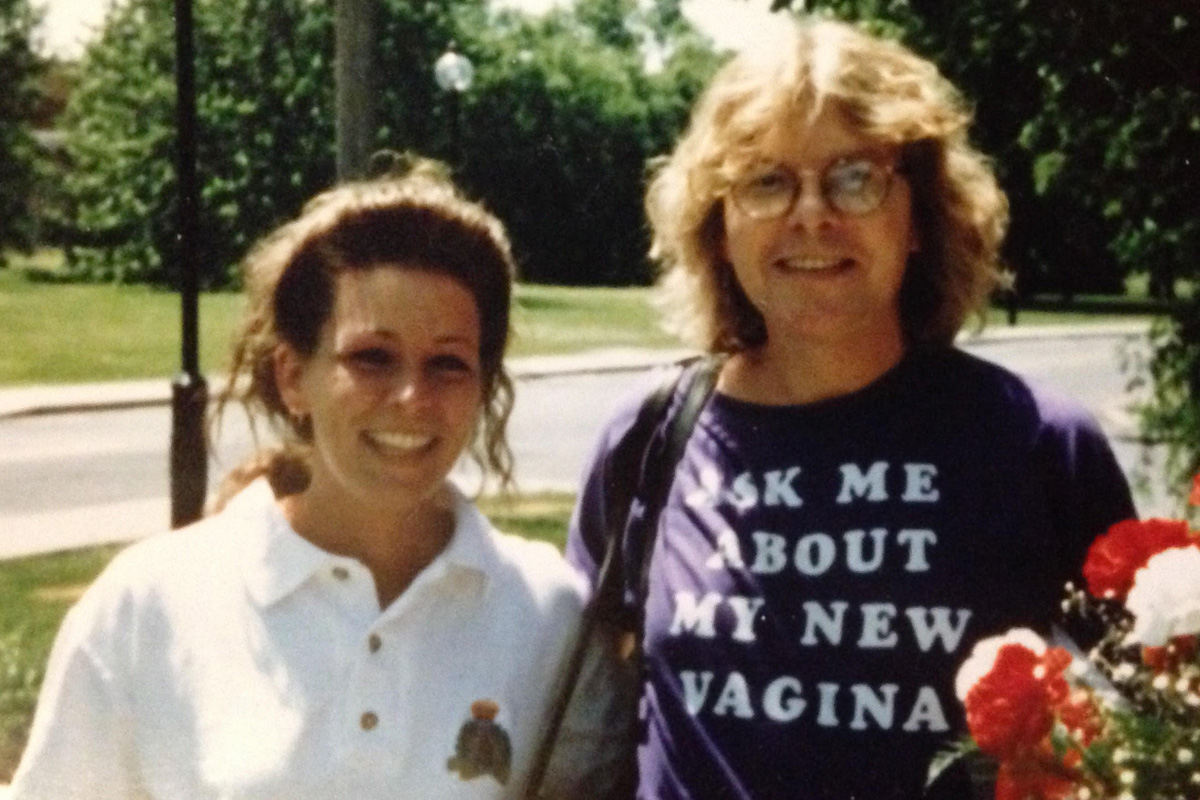

Stripped of her career and preparing to surgically transition, Simmons underwent the Harry Benjamin standards-of-care test, called the real-life test,” for a year as ordered by her therapist and endocrinologist to see if she could exist as a woman before receiving sexual reassignment surgery.

‘It Was Wonderful, It Was Freeing’

“It was wonderful, it was freeing,” Simmons says of the real-life test. “I could finally wear the clothes that felt comfortable to me, and just to be able to go right to the women’s section instead of having to sneak around because I was perceived as a woman was amazing. And not having to worry about wanting to be female. I didn’t have to resist anymore.”

During her year as a woman professor, Simmons says she became a living case study for the double standards that derive from society’s misogyny due to the difference in how she was treated as a male professor versus as a female professor.

As a male in Ohio teaching an English class with a “feminist leaning” lens, as Simmons describes, in the reviews she got for her class included “he knows more about women than any man that I have ever known,” “his views are so refreshing,” and “I would give anything if Dr. Simmons had been my father.” But while teaching the exact same course as a woman at an community college during her “real-life” test, the reviews flipped as students wrote that “she’s a femi-nazi, “too feminist,” and even said to “fire her.”

Simmons says she lost her “agency” and her “voice” in many settings in ways that she hadn’t noticed as a man because of her “white male privilege.”

“It was shocking because everything I had said as male was accepted by the class as good, but as a woman it was horrible,” Simmons says. “As a male, students rarely contested grades, but as a woman I had students throw their essays down and jab their fingers and say ‘you can’t give me a C.’”

During the real-life test, the issue of Simmons’ driver’s license being marked as male despite her presenting as a woman was a consistent worry for her, and even though she had legally changed her first name to Jes by the time of the test, the contradiction between her marker and her appearance still made her uneasy. In the late 1990s, gender-marker laws were far more complicated than they are today.

“I did have a fear of being pulled over by the police, so my therapist gave me a handwritten letter that said, ‘Dear officer, Jes Simmons is presenting as a female, and she’s in no danger to others’ and whatever else she could say to prove I wasn’t just driving around as a female,” Simmons says. “I had always obeyed the speed limit, but I was extra careful.”

The ultimate validation that Simmons got from her real-life test was an immense breakthrough in her journey, but she attributes some success she had with the test to her “white privilege” and “gender privilege,” saying that she’s never been “read” as anything other than female since her outwardly transition began.

“I could pass,” she adds.

Happy Birthday, Jes Simmons

After the 17th year of marriage to her wife, Simmons divorced her in 1997, not because she necessarily wanted to, but primarily because same-sex marriage was illegal at the time. Simmons’ depression had also reached the crescendo it had been churning toward since those nights at age 8 when she prayed that God would kill her.

Having passed the real-life test, Simmons underwent gender reassignment surgery on June 17, 1997, in Montreal, Canada. (Our first interview was on her “23rd birthday” as a trans woman). Ironically, Simmons used the severance pay after she was ousted from that private Ohio university to pay for her surgery.

Before her surgery, Simmons had a dream where she was standing in the formal dining room of her childhood home in Natchez. Jes’ mother and father were present and seated together at the end of the table.

“I looked at them, and I said, ‘But you’re dead,’ and they both smiled beatifically as my mom gestured behind me. When I turned, there was a full-length mirror,” Simmons says.

In the mirror Jes stood naked, but with the anatomy of a woman.

“I interpreted that as my unconscious saying that they would have accepted my identity and that they’re both happy for me,” she says now.

The Interruption of Peace

Surgery was a prelude to peace for Jes Simmons.

“Growing up I was never spiritual or religious, but after surgery I was walking the grounds of the hospital in Montreal, and suddenly I saw beauty in the most mundane things like birds and trees, and in a way my heart opened up to the world around me,” Simmons says.

“I remember after surgery I had this grin on my face that I couldn’t get rid of,” Simmons says in the documentary about her.

Yet, all preludes are simply an introduction for something more to come; and what came next was the opposite of peace as Simmons’ life was thrown into a maelstrom spun by transphobia and jump-started by the loss of her academic career. Simmons’ divorce and surgery put her on a steady, but uncomfortable path of wage jobs and “stealth” living for 15 years.

The solitude of her previous life as a woman trapped inside of a man’s body had transitioned with her into a compendium of isolation and forced seclusion.

“I went from getting chalk dust on my tweed jacket as a male tenured associate professor to getting butter on my blouse working concessions at a single-screen movie theater,” Simmons says in “The Jes Simmons Story.”

Many of the jobs that Simmons worked—photo-booth work, framing and patent editing, among them—had no insurance. She made so little that she periodically turned her refrigerator off to save money on her utilities bill (because she “didn’t have much in it anyways”), and her car was repossessed.

Simmons’ financial insecurity was coupled with the return of her depression that now stemmed from a feeling of “having everything taken away.” Simmons’ mother and father had died before her transition, but her brother and members of her ex-wife’s family rejected her.

Even though Laura Simmons says she saw her father “whenever she wanted,” Jes Simmons says she lost her family. “They say depression is anger turned inwards, and maybe instead of being angry about losing a career or how I had been treated, I absorbed it,” Simmons says. “I had no outlet to flood it out other than depression.”

Simmons doesn’t look at this period of her life with acrimony for those who withdrew themselves from her life, but instead explains her loved ones’ frigidity from what she assumes is their perspective. “It’s difficult for any family when someone has changed gender because in my case it felt like people’s brother, nephew and male cousin died, and that’s pretty serious,” she says.

“Did she talk about my suicide attempts?” the elder Simmons asks me about my conversation with her daughter. Laura Simmons had mentioned them to me briefly, and I hadn’t pressed her on it, I tell her father.

“That’s certainly one of the things I regret, you know, causing pain,” Simmons replies. “I had mild depression all of my life because of gender dysphoria, but what happened after surgery was that I had no one to share this feeling of ‘Hey this is the best thing that’s ever happened to me’ with. So the depression wasn’t over becoming female; the depression was over losing connections with people I loved. That was devastating.”

Laura says that those who misinterpreted the birth of Jes as the death of Joseph do not understand that “the person and the personality are still the same even if their presentation changes.”

“Presentation changes happen to everybody because we all change over time even from child to teenager, but who we are remains,” Laura says. “You have to see someone for who they are instead of what they look like, and maybe that was easier for me to do because I’m a kid, but she’s the same person.”

Simmons lost job opportunities after her transition because of the requirement that she list any names she had worked under before, which required her to list her dead, male name. “I was struggling to find work because I would get a job, and then suddenly lose it,” Simmons says. “I didn’t have savings at all.”

As Simmons unfolds this portion of her story, her strength becomes overwhelmingly apparent. She is strong in ways particular to the adversity that was foisted onto her because she dared to be herself.

Laura Simmons similarly speaks in awe at the peculiarity of this strength.

“I think about it now as an adult, and … to lose everything for something you have to do I think there would be lots of space to wallow in the loss and even question ‘Is it worth it?’” Laura says. “She’s a ridiculously strong person because not everyone could have gone through that and thrived.”

When I ask Laura where she thinks her father’s strength comes from, she pauses and sputters in veneration. “I don’t know how you pick up and keep going,” Laura Simmons says. “A strong sense of self is definitely part of it because she spends so much time thinking and feeling, but I don’t know.”

Jes Simmons tells me she had “no other choice” and that her choosing to live in the authenticity of her truth despite the despondency it came along with was second nature.

“Have you ever seen the film ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind?” she asks me.

“No,” I reply, feeling uncultured.

And then, with ease, Simmons compares the unknown, but certain, center of her strength and decision to transition to that of Roy Neary, the protagonist from the film who becomes increasingly and inexplicably drawn to the extraterrestrial in the film. Neary’s infatuation with the aliens becomes so stringent that he leaves his wife and children behind, which confused and angered many audiences who saw the 1977 film. But Simmons says she understood Roy’s calling because her calling to be herself was the same: intrinsic.

The veracity of being Jes Simmons ushered in a “dark time” in her life, she says. But in the midst of what would have collapsed the average person this same authenticity was enough for Simmons to subsist.

‘Meant to Be’: Longwood’s Warm Embrace

The end of the 15 dark chapters in Simmons’ life arrived by chance when in 2013 her daughter Laura accepted a position as a Spanish lecturer at Longwood University in Farmville, Va. Simmons left her own résumé with Longwood on a whim and wasn’t expecting to hear back at all, but she soon received a job offer.

“I was thrilled, but I didn’t want to uproot myself from Ohio and be dismissed because I was transgender,” Simmons said. On the phone she told Longwood she would need a “few days” to think about the offer. She called the university back in 20 minutes and accepted.

Still apprehensive due to the trauma from her old position in Ohio being snatched from her, Simmons emailed Longwood a detailed email about her transness expecting to have the offer rescinded. “I said, ‘I’d love to accept this, but there’s something I need to tell you,’ and so I told them, and they replied ‘OK, well, can you still teach English?’” Simmons says.

Later at Longwood as an English lecturer, Simmons came across a statue of Joan of Arc, the university’s patron saint, in Ruffner Hall, and began to cry joyfully at what she saw as an emblem of her intended destiny, marking the return of everything she had lost.

Many textbooks sum up the end of Joan of Arc’s life with her being executed for witchcraft, but as Simmons informs me, the true reason behind Arc’s execution was her decision to attire herself in men’s clothing. For Simmons, the combination of Joan of Arc’s queer coding and eternal symbol of female power have awarded the saint a position of symbolic pertinence.

“Seeing the statue was like, OK this is meant to be, and it was an eye-opening moment seeing her there,” Simmons says.

For the beginning of her career at Longwood, Simmons was “stealth” with only a few people on campus knowing she was transgender. By 2015, however, administrators asked Simmons to come out as trans in order to foster community and support for the campus’ LGBTQ students. Faculty and staff at Longwood had met Simmons with expected support when she arrived in 2013 while “stealth,” but the influx of support when she came out rivaled the amount of rejection she had previously faced.

“It was a steep change from losing a career because of who I was to being asked ‘please come out as who you are’ as a service,” Simmons says. “I was thrust into it, but I wanted to give back to Longwood and Farmville because they gave me my teaching career back, and they didn’t have to.”

Sebastian Lacoss, a future teacher who graduated from Longwood University in 2019 where he called Simmons “Pridemom,” says her presence on Longwood’s campus saved his life. Lacoss’ upbringing in Virginia had not afforded him the opportunity of knowing that he was trans or what that meant, but hearing Simmons’ story at a 2015 Longwood Pride meeting opened the door to a world where he knew he belonged.

“I asked her ‘Did you ever hope you were wrong?’ because I was hoping that I was wrong, and she told me that she didn’t ever think that she was wrong,” Lacoss says. “I was disappointed, but I was relieved because what she said meant that I wasn’t broken.”

Shortly after meeting Simmons, Lacoss began his medical transition, which he describes as “quite a process,” during which he would often lean on Simmons for support.

“Sometimes we would talk, but sometimes we would just sit in silence, and it was nice to be in the same room with someone who understands your struggle,” Lacoss says. “It was a rough year because it felt like nobody could help me, so it’s not an exaggeration when I say she definitely saved my life just by being Pridemom, and being there.”

Simmons says her decision to come out to Longwood’s entire campus and help students like Lacoss was because she sensed a disconnect between how she had always stressed the importance of authenticity in writing to her English students, but “here I was keeping secrets about being transsexual.”

“When I came out I could finally be authentic to the students, and after that so many students would write in essays ‘I’m gay or my brother is gay’ and were saying it freely without fear of being judged or graded down,” Simmons says.

For Lacoss, Simmons’ support for him and multiple other gender dysphoric and transgender students was an inspiration “to be the best I can be” and so that he can “provide the same support that” she provided him. “I wouldn’t be where I am today without Dr. Jes, and I wouldn’t have accomplished most of the things I was able to do without her,” Lacoss says.

Don Simmons, Jes Simmons’ second cousin and a writer and meditation expert, met Simmons while she was in Atlanta for a conference and said as soon as he saw her he “fell in love with her” because he noticed the same warmth and nurturing in her aura as Lacoss. The embrace of Jes Simmons’ persona was so strong to Don Simmons that without having seen a picture of her he said he knew “exactly who she was” when they first met.

“Jes is a beautiful person,” Don Simmons said. “And with the way we are in the world right now the world is a better place because of people like Jes because people like Jes have the ability to graciously allow everyone else to explore their answers.”

Don Simmons didn’t speak about his cousin as if their connection was only a few years old. His phrasing and familiarity was seasoned, and he referred to her as Joan of Arc without prompting.

Dr. Leigh Lunsford, a mathematics professor at Longwood University, is one of Simmons’ best friends. They met when Simmons overheard Lunsford mention that she was from Mississippi at a faculty event. What is most alluring about Simmons is that “she really knows who she is and she believes in who she is,” Lunsford says.

“Jes will do anything for you … almost too much sometimes because she cares about everyone, and those who are hurting in particular,” Lunsford adds. “Everybody likes her, so that alone makes everyone open up their mind around her.”

Acceptance ‘For Those Coming After Me’

Jes Simmons’ story is far from over as she heads into retirement due to COVID-19, and makes plans to continue to “give back” the unconditional love that Farmville and Longwood have given her.

“What I want to do now is help as much as I can,” Simmons says. “Having been a female for 23 years I have a lot of history behind me, and even though it’s an entirely new world for young trans people, I want to be a resource.”

In 2016 1.4 million Americans self-identified as transgender, and today a bastion of transgender icons exist in comparison to trans representation just a decade ago. But with 26 known murders of transgender people, the reality of trans individuals is still far from what known figures like Caitlyn Jenner and Laverne Cox may cause mainstream America to believe. Simmons wants her story to act as a soldier in the fight to protect trans lives.

Many Longwood colleagues have asked for Simmons to return to their classes and tell her story.

“We can cite statistics about transgender people, we can talk about hormones and chromosomes, but that’s not going to necessarily change minds,” Simmons says. “But hearing someone’s story can bring acceptance far more than anything you can read in a book. And I’m not bringing acceptance for me, but for those coming after me.”

Laura Simmons has no doubt about the impact of her father’s story because Simmons has already taught her about “being true to yourself and what a difficult journey it can be to come to love yourself.”

“Sometimes you have to take the next step without knowing if it is the right step, and she’s never let knowing where she’ll wind up deter her from taking the next step,” Laura Simmons says. “I don’t know what my journey looks like, but being raised by my dad let me know that it’s OK to guess, try, fail and try again, and that’s a lesson by example.”

The lessons in Simmons’ life might appear on the small screen as a mini-series as Katie Letien, a Los Angeles filmmaker who made the short film “VIRGINIA” with Simmons starring as the lead in 2014, has begun to dig her way through the volumes of Simmons’ journals for a possible pilot.

But regardless of what’s next, Simmons will continue being “sincere, passionate, loving, 100 times talented and intelligent in capital letters,” says Darden Wade, Simmons’ close friend.

“When I visited her at Longwood I saw where students had written about her answering ‘Who’s one of your favorite teachers,’ and the answer was always ‘Dr. Simmons,’” Wade says. “To have that much of an impact on somebody’s life, how good is that? I’m not a smart enough person to put into words how proud I am of her.”

Jes Simmons’ life is positioned toward peace as Laura Simmons says her father articulated during a trip the two took to Xalapa, Mexico, a few years ago.

“We were laying out in hammocks, and she had a big coconut she was drinking out of, and the breeze was blowing, and there were mountains on one side,” Laura Simmons says. “And I said ‘This is the life,’ and she said ‘I don’t think I’ve ever understood that phrase until now.’”

“If anyone had told me that I would spend my 65th birthday dressed as Supergirl in a Pride parade, I would have said ‘That’s insane,’” Simmons tells me with a mindless chuckle on our last phone call. Her words strike me as an indication that perhaps she isn’t fully aware of the depth of her resistance, and the refusal to succumb to defeat that poured from her with every vignette she graciously shared with me.

Jes Simmons cannot help but be an inspiration—because she has always chosen to be herself. When thinking about the “phoenix rising from the ashes” sensibility that Simmons embodies, I can’t help but be reminded of “All You Need is Love” by The Beatles, one of Simmons’ favorite bands.

“There’s nothing you can know that isn’t known, Nothing you can see that isn’t shown

There’s nowhere you can be that isn’t where you’re meant to be.”