B.B. King’s head is tilted back slightly, eyes closed in reverence, his guitar Lucille in his hand as he plays the blues. His statue is in the center park that bears his name in his hometown of Indianola in the Mississippi Delta, where the genre was born. It is music deeply entrenched in the state’s history and culture, more so really than any other place.

Blues music was a part of everywhere Africans lived in the South and on plantations, but there was a special type of music known as Delta blues. It has an intense vocal style and a strong rhythm that derives from African music, Mississippi State University African American Studies and Music Professor Dr. Robert J. Damm tells the Mississippi Free Press.

“Africans brought their culture with them, their performance practices, their ways of singing, their rhythms. And then, having been forced into this new way of living with the brutality of slavery, it was especially important for them to have some sense of identity and to find a way to celebrate in spite of the brutality and hardships of life in Mississippi,” Damm adds.

Life for Black people in the Delta was hard, in a place that had the greatest concentration of cotton planting than anywhere else in the country, he says. A large population of poor, Black people were first enslaved in the Delta and, even after emancipation, they faced vicious Jim Crow Laws starting in 1888, which legally required the segregation of Blacks and whites in public spaces. Black people who broke these laws were either harassed, beaten, jailed or lynched.

In Mississippi, more than 200 Black men and women were lynched between this decade and around the turn of the century into 1900, he says.

“So nowhere else was racism and racial oppression so ferocious as it was in the Mississippi Delta,” Damm says. “Blues comes from a terribly sad situation, but the music itself is always fun. It makes you want to dance, clap your hands, makes you want to sing along, it makes you happy. That’s the truth. It’s always cathartic. It’s feel-good music even though it comes out of sadness.”

‘Ground Zero’

Although the music had originated during slavery times in the earlier 1800s, it did not receive the name “blues” until decades after the Civil War—between 1912 and 1920. Recordings in the 1900s made the genre more popular, and artists such as Ma Rainey and W. C. Handy helped to popularize the genre, Damm says.

Blues music birthed rock and roll and influenced rock ‘n’ roll musicians like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix, he says. Blues musicians Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters were huge influences on these bands, with The Rolling Stones getting their name from a Muddy Waters song. Jimi Hendrix modeled his performance style after Chuck Berry, who would play his guitar between his legs and behind his back.

“All the early rock ‘n’ roll songs were based on the blues. All rock bands in the early days and to this day played blues songs,” Damm says.

Mississippi itself was home to a plethora of blues artists such as B. B. King, Robert Johnson and David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards. In an effort to help commemorate the figures and landmarks of blues music, the Mississippi Blues Commission created the Mississippi Blues Trail, an ongoing project of more than 100 blues markers placed across the entire state, including some in Jackson such as for the Alamo Theater and Ace Records.

The trail is long and broken into regions, so I picked one outside the comfort of home: the Delta. In February, before the COVID-19 crisis emerged in Mississippi, photographer Acacia Clark and I hit the road, two women who hadn’t met, on a road trip across the Delta and into music history. We had no reason to distance then, but the blues trail is a perfect way now to break the quarantine blues.

“Morgan Freeman calls the Delta ground zero. That’s where blues was born, that’s where blues became America’s music. If you make any list of the great blues musicians, almost all of them were born in Mississippi. The famous early blues musicians that were recorded in the 1920s, they were all born in Mississippi,” Damm says.

Bentonia, MS: Buffalo Fish, Blues and Moonshine

“This is the oldest juke joint in the state of Mississippi, or worldwide,” blues musician and owner Jimmy “Duck” Holmes tells the Mississippi Free Press. He’s leaning back, legs crossed and arm casually thrown across the wooden booth inside Blue Front Cafe. It’s the first stop on our trek along the blues trail.

The café is practically a blues museum with guitars, awards and blues memorabilia lining the walls. Multi-colored lights and vinyl albums hang from the ceiling. The café first opened in 1948 under the ownership of Holmes’ parents, Carey and Mary Holmes. It was notable for its buffalo fish, blues and moonshine whiskey, the marker says.

Notable blues artists like B. B. King and Muddy Waters stepped through Blue Front’s doors, performing for tips before the musicians became famous. Today, the café is the central site for the Bentonia Blues Festival, and live blues bands come every other Friday to perform, Holmes says.

“All other juke joints in this community were made out of wood. They consider this as being concrete floors,” he says. “When the jukebox was playing, you could dance. In wood structures, when you dance too hard, you can shake the jukebox, records would scratch. They wanted to come to the Blue Front so they could dance, jump up and shout.”

Juke joints were opened in the southeastern region of the United States during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers and plantation workers, banned from white establishments, frequented juke joints that allowed them to relax after a long work week.

“Juke” means disorderly in Gullah, and these spaces were considered rowdy and frowned upon by many people. People ate, drank, danced and listened to music at juke joints, and moonshine was a popular item sold at them during the prohibition era.

Some of America’s most popular music has roots in juke joints, including ragtime, dance music, barrel house, slow drag dance and blues. Juke joints are a part of the culture of southern states and were a haven for Black people to escape the pressures of society

The 72-year-old took over from his parents in 1970 and has been managing the café ever since. Despite its age, the juke joint gives off a rustic simplicity that you don’t see in too many buildings in the state, and it’s kept that way on purpose, he says.

“They (the state) tell me whatever I do, don’t change it. Just don’t let it fall out, don’t try to modernize it out. It’ll take something away from it,” Holmes says.

The café’s furniture has changed, but everything else is original. Holmes says he was practically raised in the café and still spends 90% of his time there, leaving only to go home, eat, sleep and bathe.

Tourists visit the café daily, he says, attracting people from around the world. The evidence is on the walls––on the outside, that is. The signatures, dates of visit and hometowns of various visitors of the cafe decorate the building’s structure—Bolivia, South Africa, Nicaragua, France, Virginia.

One visitor in particular was so moved by Bentonia and the Blue Front Café that she moved there a little more than a year and a half ago. Sandra Tucker, originally from the midwest, was on a one-year road trip, and it was a Mississippi stamp that piqued her curiosity enough to visit the state, she says.

Holmes is on the stamp. It doesn’t show his face, but his hands, which cradle a red and Black guitar that hangs on the wall of the cafe. Holmes wondered why they didn’t use the full image for the stamp, but he says a person has to be dead five years before their face can be shown on the stamp.

“I came through one February about two years ago, and this really pulled me in, but the Blue Front was closed. I came back three months later, and Jimmy signed a CD for me, and I asked if he knew a place to rent, and I rented a house from him,” she tells the Mississippi Free Press.

Three months later, she discovered the stamp she bought featured the hands of none other than Jimmy himself. The reference photo for the stamp hangs on the walls of the cafe.

“I don’t get it, but they say the reason I don’t get it is because I’m a part of it. I’m on the inside. They say I’m on the outside looking in. By me being a part of it, I still don’t grasp it,” Holmes says of the awe tourists feel.

“I’ve been here all my life. I wouldn’t trade Bentonia for nowhere,” he adds.

As Jimmy takes a seat on the porch of the café, Acacia and I sign the building, joining the hundreds of other names that adorn it—a memory made and a promise to return.

Nehemiah “Skip” James

Nehemiah “Skip” James, one of the early Mississippi bluesmen, was born in 1902 on the Woodbine Plantation where his mother, Phyllis, was a cook. His father, Edward, was a guitarist and left the family when James was 5-years-old. James looked up to Bentonia guitarist, Henry Stuckey, and learned to play the guitar and the organ as a child.

As a teen, he worked on construction and logging projects where he sharpened his skills by playing at work-camp “barrelhouses.” In 1924, he earned his living as a sharecropper, gambler and bootlegger while also performing with Stuckey. In 1931, he travelled to Grafton, Wis., where he recorded 18 songs, 13 on guitar and five on piano, for Paramount Records.

He recorded songs “Hard Time Killing Floor Blues,” “22-20 Blues,” which was the model for Robert Johnson’s “32-20 Blues,” and “Devil Got My Woman,” However, James records did not sell well and that same year, he moved to Dallas,Texas, serving as a minister and leading a gospel group. He lived in Birmingham, Ala., Hattiesburg and Meridian, Mississippi, and visited Bentonia on occasion.

In 1948, he sometimes performed for locals at the Blue Front Cafe before moving to Memphis and then Tunica County. Blues enthusiasts found him there and convinced him to start performing again. He moved again to Washington, D.C., and then Philadelphia, Pa., playing at folk and blues festivals and clubs.

He recorded some albums, but gained some acclaim after Rock group Cream did a cover of his song “I’m So Glad.” However, his popular appeal was limited due to the somber quality of his music and his insistence on putting artistic integrity over entertainment value. Nehemiah “Skip” James died in Philadelphia, Pa., in 1969 and was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1992.

Yazoo City, MS: Tommy McClennan

Notable blues singer Tommy McClennan was a man of many names and birthplaces. Though he was said to be born in Yazoo City in April 1908, as cited in Big Bill Broonzy’s book “Big Bill Blues,” his death certificate states that his birthplace is in Durant, and his birthday is Jan. 4, 1905. His mother and siblings were listed on a 1910 census in Carroll County, and by 1920, the family lived on a plantation in Leflore County.

His last name was spelled in different ways such as McLindon and McClenan, but McClennan was used on his recordings. Booker Miller knew him as “Sugar” in Greenwood. In Yazoo City, Herman Bennett Jr. remembered him as “Bottle Up” after one of his most popular songs, “Bottle It Up and Go.” Other bluesmen thought that he was from Bolivar County or Vance in Quitman County.

In the 1950s, McClennan lived on the Sligh plantation and he liked to hang out at the Ren Theater on Water Street. He was also spotted at the Cotton Club, a blues spot on Champlin Avenue. McClennan began recording in 1939 after Lester Melrose, a white Chicago record producer, looked for him.

He recorded 20 singles for the Bluebird label, and his most notable records were “Bottle It Up and Go,” “Cross Cut Saw” and “Travelin’ Highway Man.”He was known for his uninhibited singing and guitar playing. He was described as a ferocious blues singer, and in the studio he would energize his records by encouraging himself with lively comments. He moved to Chicago, though he did not perform there.

Honeyboy Edwards recalled seeing McClennan drinking heavily when he last saw him. Tommy McClennan died of bronchopneumonia on May 9, 1961, in Chicago.

Inverness, MS

Little Milton Campbell was born on the George Bowles plantation on Sept. 7, 1933, near Inverness, but spent his early childhood in Magenta in Washington County with his mother. The “little” in his name was the opposite of his physique, and it also helped to differentiate him from his father, who held the moniker Big Milton Campbell. As a child, he built a one-stringed guitar and at age 12, he bought a real guitar with money he made working in cotton fields.

In Inverness, he would perform at the town’s top blues venue, the Harlem Club, but the Leland blues bandleader Eddie Cusic is credited as giving him his first experience playing for audiences. In his late teens, he moved to Greenville where he hosted a radio program on WGVM and performed with local performers such as Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2, Joe Willie Wilkins and Willie Love.

He was known for his ability to deliver power anthems and soft ballads, and he produced many of his own records. Campbell was also known as a savvy businessman who demanded professionalism from his band and maintained his musical identity throughout his career. In 1951, he first recorded in Jackson as a sideman with Willie Love. Then two years later, talent scout Ike Turner helped him land a recording contract with Sun Records in Memphis.

Campbell developed his own style after moving to St. Louis and then Chicago. During his time in St. Louis, he recorded for Bobbin Records and was a talent scout for the label, along with blues musician Albert King. In Chicago, he signed with Chicago’s Checker label, where he mixed blues and soul music, which helped him rise to national prominence. Campbell’s most popular songs are “We’re Gonna Make It,” “The Blues Is Alright” and “That’s What Love Will Make You Do.”

In 1971, he signed with Stax, a soul label in Memphis, and in 1984 he signed with Malaco Records in Jackson, where he recorded 14 albums. He moved to Las Vegas, but kept an apartment in Memphis so he could perform and keep his ties to the southern soul and blues circuit. In all, Milton had 29 singles and 17 albums on the Billboard charts. In 1988, he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. On July 27, 2005, he suffered a stroke and passed away a week later.

Greenwood, MS

It’s mid-afternoon when we arrive in Greenwood to explore some of the town’s blues markers. We don’t go far to reach our first one, which is right across the street from where we park downtown.

The WGRM radio station is now an empty vessel, but before the 1950s, it was one of the few stations where people could hear African Americans with its broadcasts of gospel-group performances. The Famous St. John’s Gospel Singers of Inverness, for whom blues legend B.B. King was the guitarist, was among the most popular.

“This was actually the first place he was ever heard on the radio,” Greenwood Convention and Visitors Bureau Executive Director Danielle Morgan explains of King.

WRGM premiered on air in Grenada, Miss., in 1938 before moving to Greenwood a year later. It was one of nine radio stations in the state, with Blue Network running most of the programming. The radio station also doubled as a recording studio, which saw the likes of Matt Cockrell and L.C. “Lonnie the Cat” Cation with the Hines band and Ike Turner on piano. The station has been off the air since early 2018.

As we hop in the van with Danielle and her husband, Brent Morgan, to continue exploring the blues trail in Greenwood, the next stop is Baptist Town, one of Greenwood’s oldest African American neighborhoods.

“In blues lore, Baptist Town is best known through the reminiscences of David.

‘Honeyboy’ Edwards, who identified it as the final residence of Robert Johnson, who died just outside Greenwood in 1938,” Morgan says.

A few paces back from the marker is a Baptist Town sign with photos of Edwards, Robert Johnson and actor Morgan Freeman, who was raised in Baptist Town. Edwards says the community was a safe haven for musicians who wanted to get away from work in the cotton fields. He and Johnson stayed on Young Street, not far from the blues marker. In fact, it was normal for people to flock to the outskirts of town or plantations to continue the fun after venues closed for the night. In Baptist Town, musicians would play on the streets and at parties.

Blues music thrived in Greenwood with help from blues deejays, the next marker on our stop at WGNL 104.3 radio station. Blues deejays elevated the careers of artists, introducing new music and artists, as well as being the voice of the community, the marker says.

“Ruben Hughes is a local one and, of course, Ike Turner. We all know Ike. He was a deejay before he had his performing career. Charles Evers, Medgar Evers’ brother,” Morgan names. “(Hughes), the owner of this radio station, started deejaying in Forest, and then he became the owner of this station.”

As to whether blues deejays still play a key role today, Morgan says they do, though blues seems like more of a cult-like following since modern radio stations have shifted to R&B, hip-hop and other genres people want to hear today, she says.

“We’re going to pass a little blues station here in town. You can listen to it online, and they have this real cult-like following of people that want to listen to an old-school blues radio station. I’ve known of German blues-radio people that do shows from over there in Germany,” she says.

‘The Man That Sold His Soul’

Robert Johnson’s grave was a little farther out than the other markers, evidenced by the acres of land and the former Star of West plantation we passed before pulling onto the property of Mt. Zion Baptist Church. Robert Johnson was a blues singer, musician and songwriter from Hazlehurst, Miss. Legend has it that he wasn’t able to play the guitar well, so he sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads, a reverent place in blues culture, to gain the ability. The exact location of the crossroads is highly debated with some claiming it’s the intersection of Highway 61 and Highway 49, while others say the spot is near Rosedale.

The blues singer mostly stuck to performing at juke joints, on street corners and Saturday-night dances with little commercial success. In the span of his short career, he recorded 29 songs in two recording sessions released between 1937 and 1938. Not much is known about his life, only that he spent much of his time in the Mississippi Delta, where he died at age 27. He was a man of mystery.

“There’s a lot of mystery surrounding his death, too, which makes for an interesting story. He was playing at a juke joint here called Three Forks, and he was rumored to be having an affair with the juke-joint owner’s wife,” Morgan recounted as we walked to the church’s cemetery.

“When he got there, before he played, he was given some whiskey. His buddy slapped it out of his hand and said, ‘Don’t drink that,’ because, obviously, he knew the situation. And he (Johnson) said, ‘Don’t ever slap whiskey out of my hand.’ He drank it, fell ill (and) ended up dying three days later on this plantation over here.”

The woman who accompanied Johnson the night he fell ill took him to her parents’ house on the Star of the West Plantation. Morgan says many people believe the juke-joint owner poisoned him with Strychnine, a rodent and pest poison, but others think differently.

“There’s kind of another school of thought that actually the wife poisoned him because he showed up with another lady. I kind of tend to believe that a little more because poisoning is very much a female weapon of choice. We don’t really know,” she says.

Robert Johnson’s headstone is surrounded by guitar picks, flowers, hotel keys and liquor bottles. Under his name, date of birth and date of date reads “Jesus of Nazarath, King of Jerusaleum, I know that my redeemer liveth and that he will call me from the grave,” his last written words on his deathbed, Morgan says.

Johnson’s marker receives the heaviest traffic, and it’s rare that she doesn’t see someone at his grave, Morgan says. That day it was just us.

“They didn’t know where he was buried for a long time. All they really knew was that he was buried at a Zion church. Well, we have a lot of those. There’s three churches that actually have markers for his grave,” she says.

A blues historian cracked the mystery by talking to people in Greenwood who knew him. Enter Mrs. Rose Eskridge, whose husband worked on the Star of West Plantation. He was the one who dug Johnson’s grave. A preacher was brought in to say a few words, and Johnson was put to the earth. Without her eyewitness account, Robert Johnson’s real burial site would still be a mystery, much like the man himself.

“You can’t come to Greenwood and not go to the grave,” she says.

Morgan says the blues shaped a lot of what Greenwood is. The city was a cotton capital because it was a shipping point and prior to that, blues was born in the field, she says.

By 1850, slaves outnumbered white people five to one across the Delta. Plantations started arriving near the Mississippi River, increasing slave numbers. For example, in Coahoma County, the total slave population increased 226% from 1,391 to 5,085. In Bolivar County, the numbers increased from 2,180 to 9,078 slaves, and Yazoo County had the greatest number of any core or partial Delta county with 16,716 slaves.

Damm says enslaved Africans had the field holler and were allowed to maintain work songs because the overseer saw that it made them more productive. Their way of making music, singing while working with a rhythm that underscores the work, is what became a part of the blues, he says. Blues was a form of communication and expression.

“The progression from the field hollers that they would sing in the cotton fields. Without that industry, blues may not have ever been born,” she says.

As we headed back into town, there was really only one question left to ask her.

“Any food recommendations?” I asked.

“We have The Crystal Grill, which is like a classic, southern (food). They have everything. If you want it, they have it. They’re kind of famous for their dessert. They have these pies with mile-high meringue. They have really good cheesecake,” Morgan says.

“Then we have a great barbecue place called Drake’s BBQ. We have a couple barbecue places, but Drake’s is my favorite. It’s kind of a small place, but really good.”

The Crystal Grill it is.

Indianola, MS

“Did you go to Club Ebony back in the day?” I ask Sylvester Pomeli, who was sitting inside Cozy Corner Café.

“I did. On a Sunday evening, you’d see about 200 young women looking like y’all. That was the place,” he answers. “Every blues star that’s a blues star came to Club Ebony.”

“When Little Milton, B. B. King or Albert King would come to town, it would excite people from miles around. Greenville, Greenwood, Ruthville, Belzoni. Because it was like going to a big concert in Jackson. It was the show place of the Delta,” Ronnie Ward, owner of Cozy Corner, adds.

After a quick lunch of burgers and fries at Greenwood’s Crystal Grill, we head back to Indianola, Miss. We had passed through earlier in the day, but the neighborhood’s historian, Ronnie Ward, wasn’t in at the time. Inside Cozy Corner Café, Ronnie is regaling us with stories about Club Ebony, the hotspot for blues artists and Black people back in the day.

Ward says people would come from everywhere, dressed in their best ’fits. He remembers partying at the club when it had a disco, and Bob Kay, who deejayed for WJMI in Jackson, would come to the club on Friday and Saturday nights to spin.

“It was awesome. I’m talking about standing room only. You talking about ‘the roof, the roof is fire’? We don’t need no water, let that mother burn! It was some partying then,” Ward reminisces.

Johnny Jones built Club Ebony. Ward describes him as an immaculately dressed Black man with white shirts, ties, brimmed hats, and driving the finest cars. From the stories he heard from his father and others in the community, if there was a Black mafia, many suspected Jones was the head of one.

The club used to be called John’s Night Spot on Church Street until he moved it a few streets over on Hanna Avenue. It was built in the ’40s and was the biggest club between New Orleans and Memphis, Ward says.

“It was a beautiful structure if you could see some of the pictures. It had an original glass marble bar, and it had lights in it. It was awesome,” he says.

“Mr. Johnny Jones was the man. He had some stuff that people hadn’t seen. The other part was like a tile floor, but a pretty tile, like back in the day they had the square tile with the shine. Like a dance floor. You get to the dance floor, it would be a disco-style color. It had two stages. It had one to the side and one to the very back. Disco ball at the top. They had plenty of mirrors, so you could look at yourself.”

“Once you pay and pass the bar, the mirror was all the way down. You can see yourself from head to toe before you enter into the back. Everybody dressed up before they go through the door,” Betty Ward, Ronnie’s wife, adds.

Club Ebony saw stars like Ray Charles, Bobby Bland, Albert King, Willie Clayton and more. After Jones’ death in 1950, the club had various successors, with Mary Shepard being the last. She ran the club for 34 years before retiring in 2008.

B. King then purchased the club and later, he donated the club to the B.B. King Museum. The club was closed when we ventured over to the space, the rusted sign and aged structure giving hints that there hadn’t been any partying inside for a long time.

“I had a chance to be running Club Ebony, but I had just opened this place. B. B. King kept asking me, ‘Ask that boy what he think he could do with the club.’Guess what? That boy didn’t never reply,” Ward says.

“Sad. How people be trying to help you, but you be so set on what your goals are at the time.”

‘Indianola’s Farish Street’

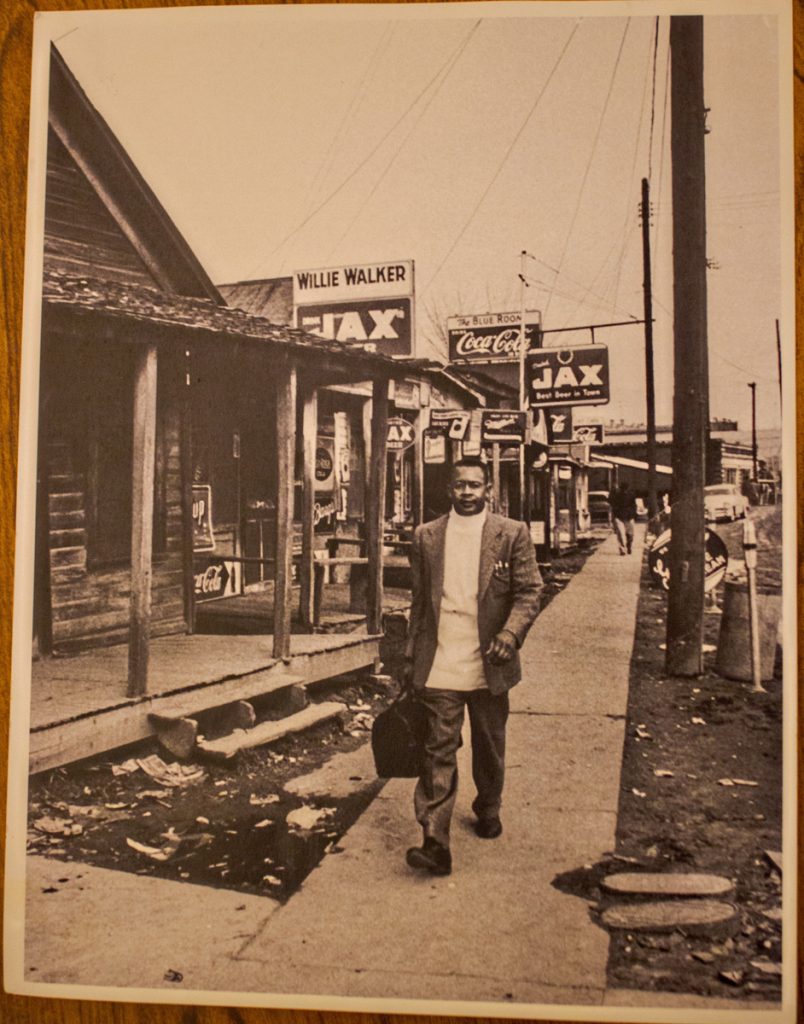

Betty Ward pulls a photo out of a manila folder from behind the bar. In the photo, a Black man with a briefcase in hand is walking past a row of businesses.

“This used to be Church Street. Right here next door, and that was the doctor. That was Dr. White,” she says.

Cozy Corner Café sits at the intersection of Mill and Church streets, the latter of which catered to the needs of the African American community during the segregation era with ice-cream parlors, tailors, restaurants, churches and lounges. Its best comparison is to Jackson’s Farish Street District, Ronnie Ward says.

Betty Ward says she doesn’t know as much about Church Street’s history, but her husband knows it inside and out.

“Ronnie can tell you who died across the street, especially Church Street. When the tourists come through, they tune in like wow. He just gone go on and on and on and on,” she says.

“Church Street was called Uptown,” he begins. “Uptown is where the Black people had all of they things, such as movie theaters, dry cleaners, shoe-shine parlors, barbershops, ice-cream parlors, cab stands. The doctor’s office, which was Dr. White, a Black doctor.”

“Next door on the first slab was Eddie Phillips Pool Hall,” Ronnie Ward continues. “The next one was the Sunrise Cafe. The next place adjacent to that was Vernon Taylor Dry Cleaners, and that was a tailor shop. Then the next building, it used to be Vince McGruder’s, which was the Blue Moon. That’s where you seen the wooden juke joints. But in the late ’60s, two Black men named Will Fountain and J. W. McGee came together and built a liquor store and a barbershop complex there.”

Ronnie Ward remembers the phone booths not too far from White Front Cafe, an old wooden building specializing in chicken and rice. He remembered Ms. Canary’s Place, Sugar Shack, The Key Hole Inn, which Mary Price had run since the ‘40s. Chicago Club. The S&C building.

He ran down the entire list of businesses occupying Church Street before ending back at the marker, where Bryant Chapel used to sit. It’s also the church where the pastor would allow civil-rights activists fighting for the vote to hold meetings.

“Does Church Street look like that now?” Betty Ward asks rhetorically.

It doesn’t. Church Street is peppered with businesses here and there like George’s Lounge, Courtyard Blues Bar and Grill, Club Zone and Yuck’s Food Store. Saint Benedict the Moor Roman Catholic Church and Mt Beulah Baptist Church sits a few paces down from the café. Some buildings on the street are boarded up and there’s an empty lot across the street from the cafe. It’s definitely not the vision Ronnie Ward paints from his childhood.

Ward says Church Street’s decline has to do with the older generation dying off, and the younger generation taking no interest in preserving the street’s history, as well as crack cocaine and unions. A lot of companies, like Delta Pride and MTD, which employed a large number of people and brought money to the town, were shut down, he says.

“If I go to my constituents, and I say, ‘Let’s get together and make a 501c3. We’re going to form a committee where we’re going to call it the Church Street Community Business District, get it wrote off as a 501c3, tax exempt.’ All we have to say is, ‘We’re going to put so much back into the community,’” Ward says.

But when he comes to the community with plans for revitalization, he is met with dissension and attitudes, he says. No one wants to come together. He’s thinking of taking matters into his own hands because he sees potential in revitalizing the neighborhood, especially when people come back for homecoming, which makes money for the community.

“We fill up motels in Greenville, all the ones in Indianola, Greenwood and Cleveland. Anytime you get an impact like that, you’re almost competing with the Delta Blues Festival. And now what we gotta do is keep them here because they’ll just come here for that one Friday, and they’re gone,” he says.

However, Ward is also ready for retirement and would like to be able to pass his business down to his children and spend time with his grandchildren.

“At 65, I’m trying to pull out. I want to get my fishing boat and have me some fun,” he says.

For now, he seems content in keeping the stories of Church Street alive.

“I enjoy people. I really enjoy people, especially when I see young ladies like y’all. And young men that want to know where it started, how it all started. It means the world. Sooner or later I’ll be gone and won’t nobody do it,” he says.

To learn more about the Mississippi Blues Trail, visit msbluestrail.org/.

CORRECTION: The original version of this story misspelled the names of Ruben Hughes and Mrs. Rose Eskridge. Both are corrected in the above story, and we apologize for the errors.