Students, to you ’tis giv’n to scan the heights

Above, to traverse the ethereal space,

And mark the systems of revolving worlds.

—Phillis Wheatley (To the University of Cambridge, in New England)

Senate Bill 2726 has died a timely death. The bill would have closed three public Mississippi universities. Many believe that three Mississippi HBCUs (Alcorn State, Jackson State, Mississippi Valley State) would have been on the chopping block. Not surprisingly and fortuitously, HBCU alumni rallied along with supporters of these and the other public Mississippi universities to overcome this bill before it could do any harm. This legislative tactic may have stalled, but it helped to reveal a potentially troublesome mindset. The idea that closing schools is a productive measure to combat declining enrollment is not new to the national discussion.

The more problematic issue is that Black schools were or could be singled out. Jackson Public Schools decided to shut down multiple schools in a decision that disproportionately affects Black students. The consequences of any bill that would shut down HBCUs would have the same impact. Senate Bill 2725 has been introduced. This sister bill to 2726 would formulate a task force with the power to recommend the shutdown of universities based on select factors.

When I investigate the potential takeover of Jackson water and sewer, the formation of an unconstitutional court in the capital city, the closure of Black public schools, or the secret homicides and burial of Black citizens, I don’t see coincidence. I see power. Or more accurately, an attempt to assert power over Black people to enforce a political agenda. These moves serve to discredit the dignity and humanity of Black people in Mississippi. The education specific decisions are an affront to the larger legacy of Black education in America.

Black Education as a Liberatory Practice

For centuries, Black Americans—enslaved, free, entrepreneurial, revolutionary and alive—have always been zealous about the education of our people. We see education as a liberatory practice. In America, the education for Black people has always been a revolutionary undertaking. To be Black and educated in this country is to demand a reckoning of our humanity and potential. It is to demand that the world treat you not as an equal, but in direct proportion to your identity—an identity that you choose to claim for yourself. For Black people to tell their own story, name themselves and live out their own destiny as they see it has always been revolutionary, if not criminal, in this place.

Education has been a tool, not one that we have been given, but a tool that we have unearthed for ourselves. With it we choose to sculpt a life bigger than the class we are born into. This means that education is and always has been a threat to the powered class of America, a threat to white supremacy in thought and practice. An educated Black person holds within them the potential to rewrite law, craft legacy, raise generations and challenge injustice. I must admit that as a Black educator I am pridefully biased in my thinking. However, I am confident in my understanding as I stand on the shoulders of generations of educators whose work paved the way for my life.

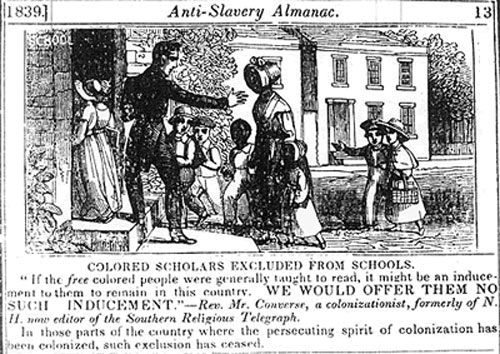

There is a consistent through-line and legacy of Black educators extending all the way up to today. Historically, for Black educators, teaching and being taught was a dangerous undertaking. The oppressive class thought that to educate Black people put their way of life in jeopardy. They were right. It becomes almost impossible to degrade and abuse educated people. If the subjugation of Black people was or is a cornerstone of American capitalism, then the education of those people stands in direct opposition to American economic advancement. This is a hard fact for many to rationalize as it is opposed to the American mythos of liberty, freedom and meritocracy. Mass incarceration is our 21st-century example of Black bodies being transmogrified into dollars. Add to that the privatization of prisons and the mortifyingly low wages inmates receive for their labor.

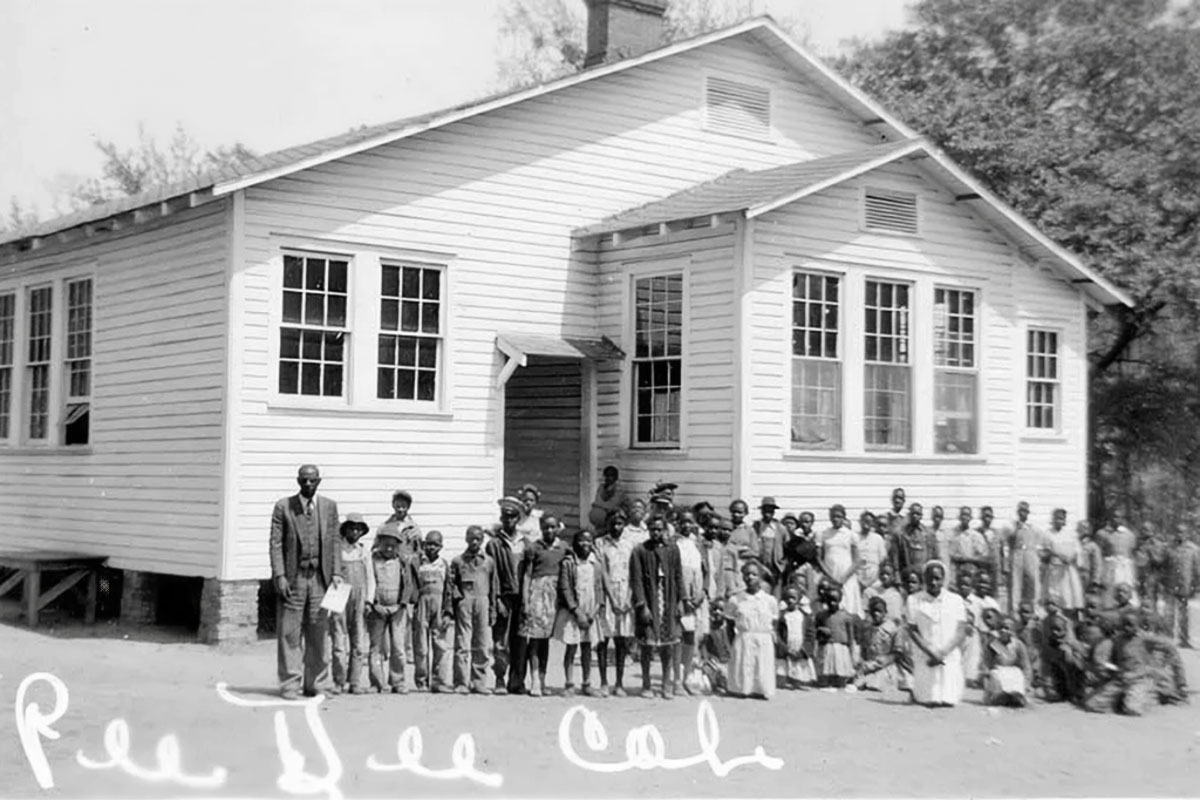

The history of Black education as a subversive anti-white supremacy measure was clearly seen during American enslavement in Mississippi. The narrative of formerly enslaved person Mandy Jones espoused one of the ways in which enslaved people learned to read. According to Mandy, they would hide in what could be described as pits and have a hidden school. Enslaved people knew the risks and intentionally educated themselves in secret. They believed so strongly in learning that they elevated the need to be taught over their own safety. This is the legacy of Black education and pedagogy. To be Black in America means to be born into a lineage of resistive learning, it is to believe that in order to truly be alive, you must be free, and in order to be free, you must learn. This is the genetic history encoded into the pedagogical DNA of Black teachers. We teach by any means.

If Black schools are closing in Jackson, if a bill passes that leads to the erasure of historically Black colleges and universities, I am confident that Black educators will find a way. I am also confident that we shouldn’t have to. Scholar-historian Heather Williams asserts that Black people, enslaved Black people, educated themselves. They worked to secure knowledge secretly and routinely despite being thought of as not intellectually able to hold understanding.

The idea of Black people being subhuman and thus sub-intelligent is older than the United States. In 2009, former Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour introduced a plan to consolidate three Mississippi HBCUs. Though the plan failed, the idea seems very much alive in 2024. It’s hard not to see the closure or potential closure of Black institutions of learning as continuous additions to an American legacy of the criminalization of the Black mind. It was illegal to learn then; it is apparently unprofitable now.

This writing is a bridge. It is a way to connect and remember from whence we have come. It is an admonishment that we must not in practice or thought go back. We must not retreat in our pursuit of knowledge, which is a divine expression of Black humanity. It is not a threat to anything good in America. It is a threat to the human evils that have set the foundation of this country. Much like a growing adolescent on the verge of adulthood, America must decide who it is growing to be. How will it proceed from the racially prejudiced embryonic fluid in which it was formed? The toddler-esque stumbling through Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement must lead us somewhere. It is for us to decide our destination.

When I say that anti-Black-intellectualism is a historical staple of white supremacy, I am not simply exaggerating or espousing some Black-pride saturated defensiveness. I call to remembrance the words of Thomas Jefferson, a founding father of our country, who himself had a disdainful history with Black people. Jefferson in his criticism of the American author and poet Phyllis Wheatley said, “…The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.”

To Jefferson, her Blackness was so limiting that she could not truly be a poet worthy of the thought and respect necessary to garner critique. It would appear that for centuries white men have seen the intellectual ability of Black women to have and express thought, particularly thought in contrast to white ideals or sentimentality, as a threat. See the recent words of Frank Hester, UK conservative and donor, directed toward the first Black Woman elected to Parliament, Diane Abbott: “It’s like trying not to be racist, but you see Diane Abbott on the TV, and you’re just like, I hate, you just want to hate all Black women because she’s there, and I don’t hate all Black women at all, but I think she should be shot.”

There is nothing as threatening to a white-supremist power structure as learned Black people (especially Black women). We, Black people, must continue striving for the heights of educational attainment, and pushing toward knowledge of ourselves and our world. The visceral answer to Black knowledge begets only one appropriate response—that Black people, in K-12 and collegiate spaces continue to make them sick.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.