Each year, someone forwards me an article about the “controversy” surrounding Dr. Malanga Karenga and Kwanzaa. The most recent one sent to me is Bruce A. Dixon’s “Why I Can’t Celebrate Kwanzaa.” I’ve been aware of these issues for so long that I’m surprised that many people today don’t know them. Yet, I also realize that few people actually research what they claim to believe or the practices that they execute daily. I, however, tend to be different as I rarely do anything without researching its history. For instance, when people ask me, “If you are married, why don’t you wear a ring?” I simply reply, “because I don’t worship idol gods, and if you knew the history of rings you probably wouldn’t wear one either.” I could continue with such things, like people who identify as Christian but still use the term “Easter.” That cracks me up. And, I’m not going to waste time commenting on that tree that they erect in December. Just know that you are celebrating and worshiping Nimrod with that tree and not Yeshua.

I’ve known about the accusations and facts regarding the life of Karenga for years, and they have never changed my embrace, support and practice of Kwanzaa’s principles for a few reasons. As a quick aside, however, I do think that it’s important to recognize Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate as a co-founder of Kwanzaa and is equally responsible for the spread of Kwanzaa. It seems that both of them had the idea for a new Black Holiday and shared it at a Black Nationalist conference in 1966 at UCLA, building on and adding to each other’s concepts together.

Moreover, based on her testimony, Karenga named her “Sister Makinya,” showing his deep respect for her work as a scholar and freedom fighter. Unfortunately, as often happens, the most noted or charismatic person usually gets the credit for an idea, especially if the choice is between a man and a woman. Westerners, especially Americans, love the mythology of individualism over the truth of collective (cultural) work and often seek to identify the sole “leader” of a movement because it satisfies humanity’s fetish for celebrity worship. Yet, they had the idea simultaneously and co-developed it. Some are now starting to promote Sister Makinya as the “rightful” founder of Kwanzaa solely to avoid the Karenga controversy. But that’s as myopic and hypocritical as acknowledging only Karenga.

I don’t celebrate holidays or birthdays, which means I don’t regularly schedule time to acknowledge them or attend events for most of them. However, my pops taught me to execute Kwanzaa as an evaluative ritual rather than a holiday, so that’s how I engage in it.

I’m dedicated to following and manifesting Kwanzaa’s seven principles in my life: Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity) and Imani (faith). If more Black folks practiced these seven principles, our lives and sovereignty would increase exponentially. So, I take a moment at the end of the year to evaluate if I have lived by those principles and to rededicate myself to living them. Yet this is no different than what I do every night before I go to bed. I ask myself: What have I done to improve myself, my community and the world as a way to keep myself focused on the goal of using writing to make life better?

White Transgressions v. Black Transgressions

As for Karenga, I’m well aware of all of his shortcomings and treat him like I do every other person who has also done good and bad: I take what I can use and discard the rest. Next, y’all gon’ tell me that we should erase Martin Luther King Jr., from history because he had an affair. Moreover, which Napoleon Bonaparte should we remember—the revolutionary or the dictator? Should we simply reject and erase from history the Napoleonic Code because Bonaparte was an insecure little man who was so jealous of Gen. Thomas-Alexandre Dumas—a Black man leading European troops—that he allowed Dumas to languish in jail for two years just to teach him a lesson about questioning his leadership? Sadly, I find that even Black folks are more forgiving of white transgressions than they are of Black transgressions. So, if one’s reason for not celebrating Kwanzaa is because of issues with Karenga, then that person is a hypocrite for celebrating Thanksgiving (Kill-an-Njun-and-Take-His-Land) Day.

Second, as a student of the Black Power and Black Arts Movement, having a father who was part of that movement to a degree, I learned early that one of the primary differences between both movements is that the Civil Rights Movement was about protesting white evil while appealing or petitioning to white goodness. The Black Power Movement was about resistance of white supremacy, rejection of white supremacy, and renewal of one’s African and African-American self. As such, those who embraced both movements understood and believed themselves to be at war with America and that violence was a part of that war. Dr. Akinyele Umoja’s book, “We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement,” discusses this well.

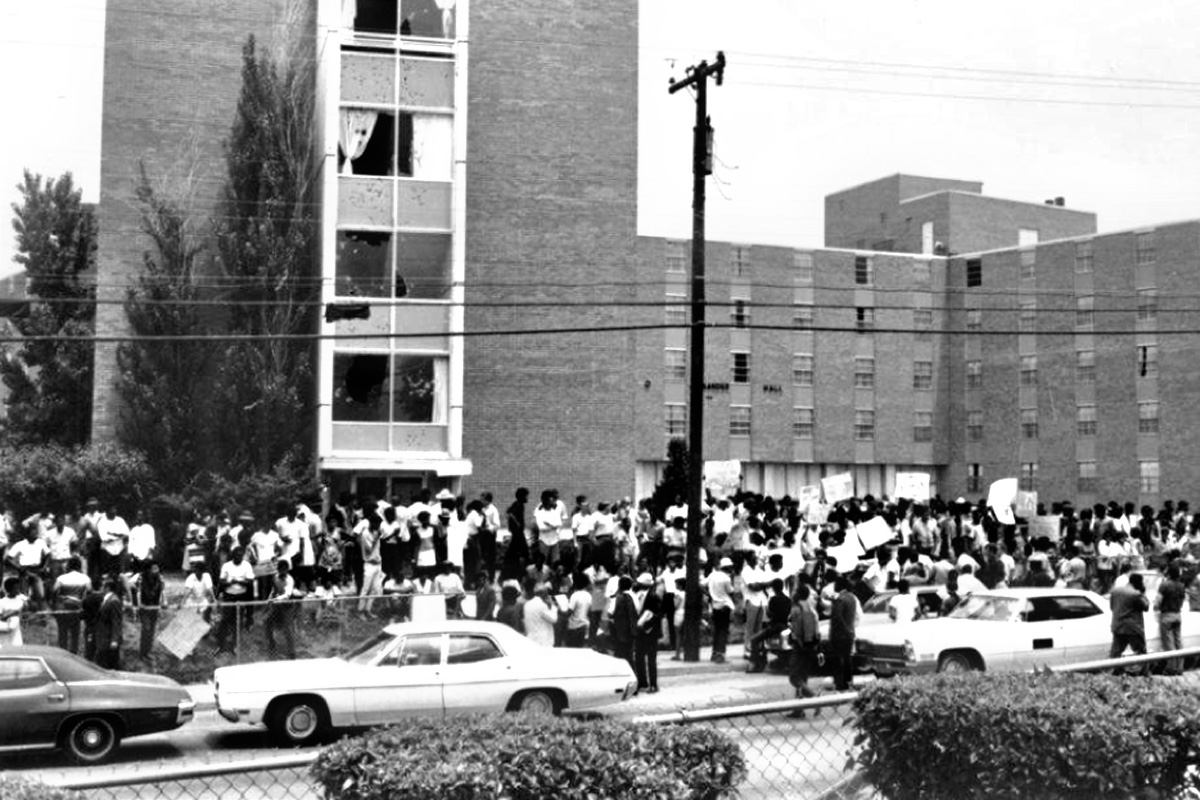

After returning from Vietnam, my father helped establish the Vet Club, which was an armed resistance group that, among other things, patrolled J. R. Lynch Street in Jackson, Miss., because white motorists refused to obey the speed limit and struck two Jackson State University students with vehicles. It was at that moment when JSU students decided that every white motorist disobeying the speed limit would get a brick through the window. Thus, my father and other Vet Club members would patrol the street to help keep students safe. (Of course, not even their work could stop the Jackson Police Department, the Mississippi Highway Patrol and the Mississippi National Guard from shooting up a JSU dorm, Alexander Hall, killing two students and wounding 11 others on May 14, 1970). Unfortunately, when one is “at war,” the use of violence can become misdirected at people who are fighting the same enemy as you because you disagree on the tactics or believe that the other person is really trying to help the enemy.

Where Civil Rights Movement groups, such as NAACP, CORE, SCLC, SNCC, and others were able to unite and establish COFO, most Black Power Movement groups were unable to develop the same type of collective. However, it should be noted that COFO only really lasted as long as Freedom Summer and that immediately after Freedom Summer, those Civil Rights Movement organizations returned to their own individual work and agendas. So with this understanding that violence was always part of the Black resistance movement, it cannot be surprising that, sometimes, violence was aimed at other Black people in the same manner that white people killed President John F. Kennedy because he was a perceived threat to white supremacy as they understood it.

This is one flaw in Dixon’s article in that he demonizes Black folks for using violence against each other, but never mentions how white folks have always used violence against each other in the same organized manner.

Or, as I state in my poem, “Revelations of a Bastard Child”: “If Africans are uncivilized creatures at war, is the tribal warfare any more civilized when it’s in Kosovo? Nat Turner fights for his liberation, and he gets hung. White folks commit treason and get a flag and a song.”

It seems that Dixon’s article is polluted with the same hypocrisy.

Next, the reason that Malcolm X knew that some members of the Nation of Islam wanted to kill him is because he, himself, stated that had any man done what he had done just five years earlier, “I would have killed that man myself.” I’ve often thought that it is disingenuous for people to be “surprised” that the Nation had a hand in Malcolm’s death because, again, Malcolm stated that he would have done the same. Of course, I try to inform people that the FBI and CIA had just as many hands in the killing of Malcolm as the Nation because they had their own spies and informants influence the movement and decisions within the Nation.

Kwanzaa Is Bigger Than Karenga

This gets me to the specific question about Karenga and Kwanzaa. One should notice that a lot of Dixon’s article contains insight from people associated with the Black Panther Party. That’s only relevant because, yes, the Black Panthers and Karenga’s organization, US, had a lengthy dispute that escalated into armed violence on more than one occasion. There is, at least, one documented shoot-out, but other incidents are known to have happened. Unfortunately, many of those people, on both sides, have never forgiven each other or have never found a way to work with each other. But, to be clear, it wasn’t just Karenga’s organization US shooting at the Black Panthers. They were shooting to kill each other, so the Black Panthers don’t get to play the role of innocent victim—especially since the Black Panthers had a history of “armed confrontations” with several groups, Black and white. Again, they all believed that they were at war.

| Dr. Maulana Karenga explains the meaning of Kwanzaa and why the holiday was created. Video courtesy African Holocaust Society/YouTube |

As for the kidnapping and torture of the women, Karenga is on record that US, like the Black Panthers, had a way of “dealing with” traitors, and those two women were, according to Karenga and others, working with local authorities as spies. I don’t know how much of that is true, but, again, US, the Black Panthers, and the American government all have “their ways” of “dealing with” traitors. Moreover, Karenga served his time, and I don’t know what else one would want from someone who has served their time. When America apologizes for torturing, killing, and incarcerating people for political reasons is when I’ll expect the same type of apology from Karenga, the Black Panthers, or any other person or group who was at war with America for the liberation of African peoples. Maybe Dixon can write an article about how we should not celebrate St. Patrick’s Day or that we should not support labor unions because of the long and well-documented history of Irish and Italian criminal activity both within and outside “legal” means.

Taking all of the above into consideration, none of it has moved or influenced me not to embrace the principles of Kwanzaa as Dixon is right about one thing: Kwanzaa, the idea, is bigger than Karenga. Furthermore, Dixon is being disingenuous, which makes him an untrustworthy journalist and scholar because he is acting as if the Black Panther Party were not just as violent toward other Black organizations like US. Regardless of the side on which they fought, a lot of people were harmed, and for Dixon to paint such a one-sided picture is laughable at best. I don’t think that any Black person is obligated to celebrate or even honor Kwanzaa, but I do think it is more harmful when Black people make decisions that are not based on empirical data.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.