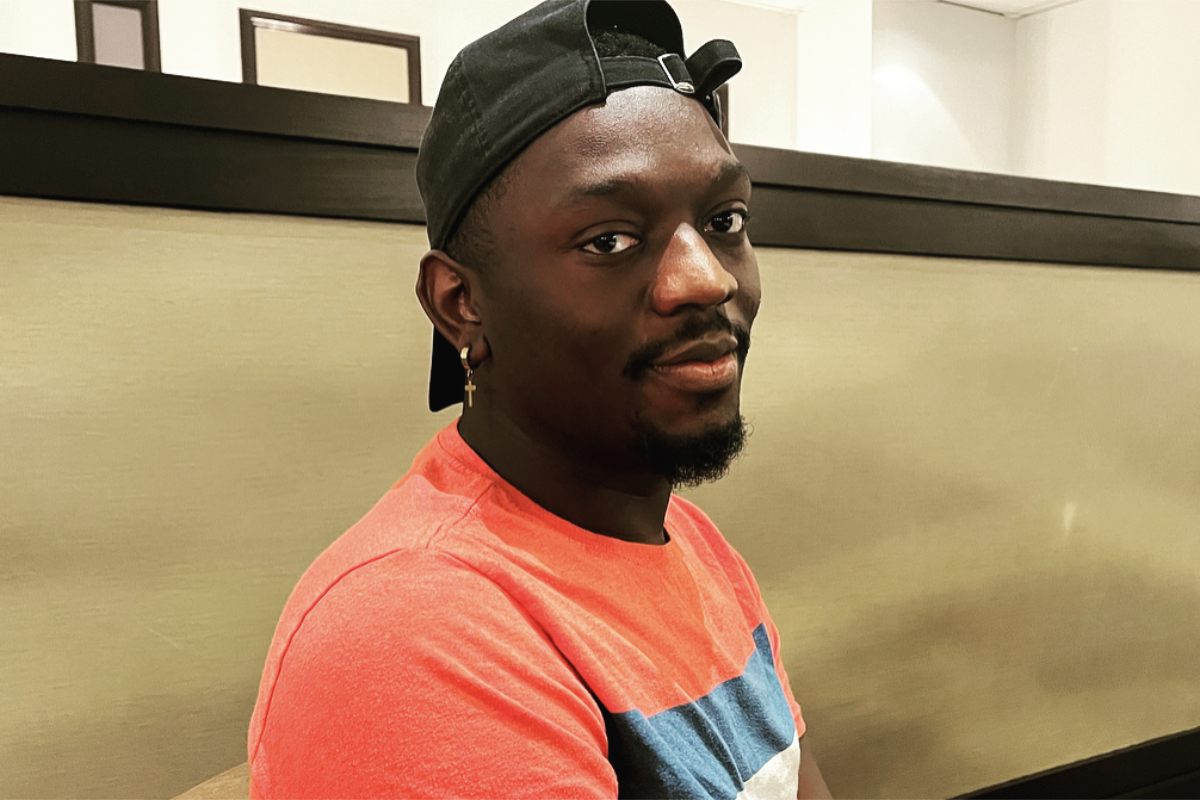

Corey Burnside was a shell of his former self when he met Cedric Sturdevent at a Greenville, Miss., support group for Black gay men in 2017. His previously contagious laughter was silenced; his weight was deteriorating.

Four years earlier, Burnside had gone a year without talking to anyone he knew—not even his mother. His sisters only made contact after arriving at his apartment for a wellness check six months into his self-imposed isolation in 2013.

By all accounts, Burnside, then 18, was supposed to be entering an exciting chapter of discovery and possibility. He had just signed a lease for an apartment that granted him the independence he craved and a reprieve from a strained relationship with his mother after he told her he was gay.

“I didn’t hear from her for the first four or five months,” Burnside said. “She wanted nothing to do with me. She said, ‘Well have you told your friends? Have you told anybody else? Have you told your family?’” he recalled his mother asking.

Burnside developed an intense fear of rejection that kept him from opening up to relatives and creating close friendships, resulting in him spending most of his high-school experience in isolation. With a newfound independence, Burnside had an opportunity to explore dating for the first time.

‘I Just Started Getting Super Sick Out of Nowhere’

For Black gay men in the Mississippi Delta, where LGBTQ-affirming spaces are almost non-existent, dating apps provide the most convenient way for people to meet.

“He was number one in his class in the Marines,” Burnside said, describing a man he met on the popular dating app Jack’d who would become his first boyfriend.

“He was three years older than me,” he continued. “We worked at the same place, and it was all falling in line to me. We were supposed to be together.”

Young, inexperienced and blissfully naive, Burnside, now 28, described this chapter from his past as one of the darkest periods of his life.

Having no proper education about safer sex practices, Burnside recalled being oblivious about the possibility of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection—especially since he’d only had one sexual partner.

“I just started getting super sick out of nowhere,” he said.

His family has a history of sickle cell disease, so his grandmother urged him to get tested. Burnside went to the health department for testing soon after he began experiencing flu-like symptoms.

“They said, ‘We don’t test for sickle cell, but you can get an HIV test.’ In my mind, I don’t know anything about HIV,” Burnside said, recounting his confusion. “I don’t know why they’re asking me this.”

He told the Mississippi Free Press that the possibility of being exposed to HIV never crossed his mind.

“This is the only partner I’ve ever had sex with,” he said. “I took the test and it came back positive.”

The results sent a shockwave throughout his system that, in many ways, felt like an out-of-body experience. Burnside was no longer on the receiving end of life-altering news, but a casual observer of someone else’s misfortune—until he became a target for the stigma attached to living with HIV in rural Mississippi.

“After my results came back, and I remember this so clearly, the disease-intervention specialist asked me, ‘So how many guys have you slept with?’” he said. “That was his first question. And at this point, I was still in denial. I said, ‘None.’ And he was like, ‘Are you gonna sit here and lie to my face?'”

Burnside described the interaction as “aggressive.”

“You could hear him outside of the doors. That’s how loud and aggressive he was,” he said.

Following his diagnosis, Burnside explained that he spiraled—attempting suicide four times and falling out of medical care for the next four years.

“I just wanted out of here,” he said. “I didn’t know what my life would consist of, and I had nobody to help me navigate that process.”

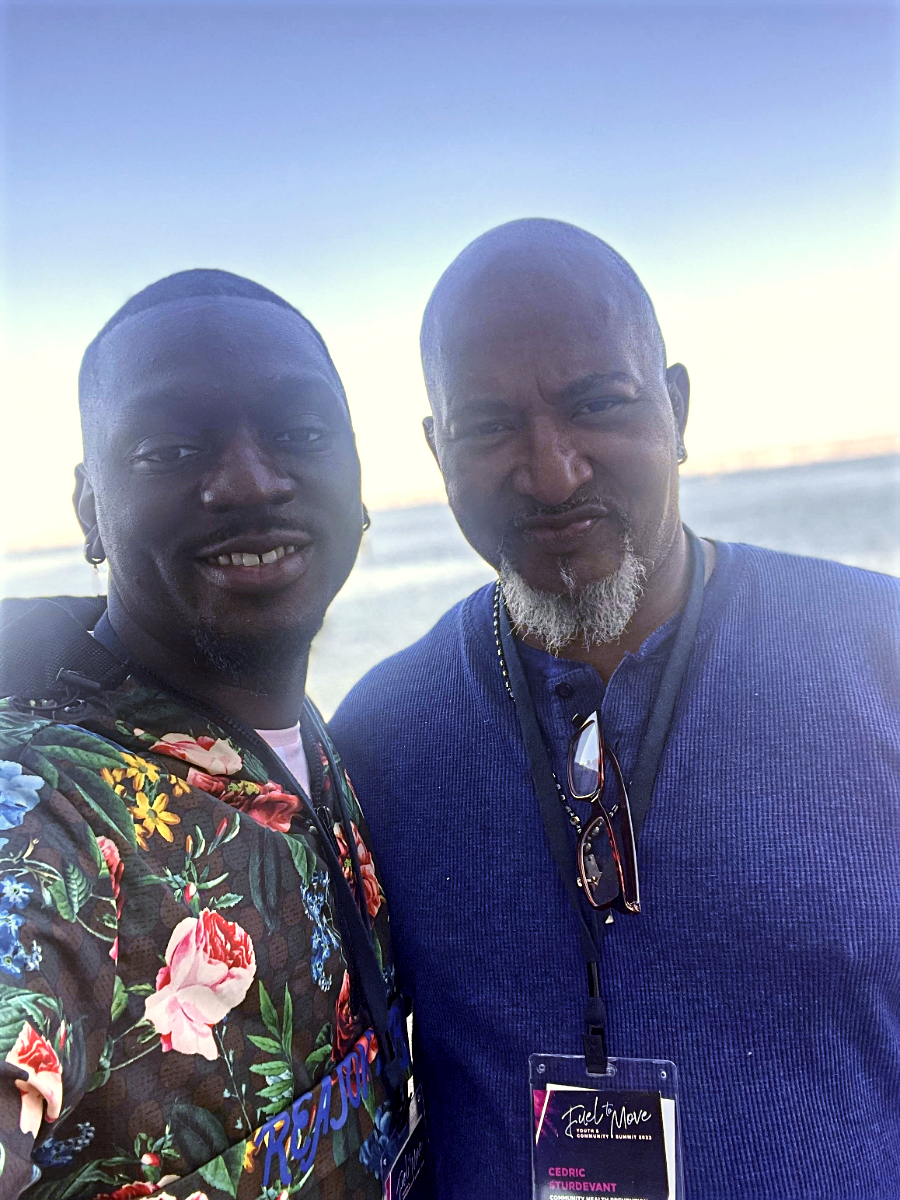

Help arrived in 2017 when Burnside crossed paths with Sturdevant, who would become a father figure and change the trajectory of his life, at the support group at the Crossroads Clinic (now Adult Speciality Care) in Greenville. Burnside’s biological father had died of suicide before his first birthday.

‘There’s No Bridge I Wouldn’t Cross’

Cedric Sturdevant, 58, is a co-founder of and serves as the executive director for the Greenville-based nonprofit Community Health PIER. PIER stands for prevention, intervention, education and research.

He has been living with HIV for 18 years. He met Burnside in his former role as a consumer speaker with Merck Pharmaceuticals, where one of his assignments included speaking to an HIV support group at Crossroads Clinic where Burnside volunteered.

“He told me he wanted to do what I did,” Sturdevant said.

“I still don’t know why (I said that) to this day,” Burnside jokingly recalled. “Cedric was like, ‘Are you sure?’”

The two soon began attending HIV-advocacy meetings throughout Greenville and Jackson, with Sturdevant often transporting Burnside between the two cities to nurture his growing interest in HIV work.

“I’m going to walk you through. I’m going to make sure everything you want to know and need to know, you will know,” Burnside remembered his mentor telling him.

Sturdevant was uniquely positioned to mentor Burnside and get him back into care after living through the same denial, stigma and HIV health-related issues himself. Sturdevant also decided against pursuing care after his 2005 diagnosis.

“I really didn’t want to know; I’m already living with one chronic disease,” Sturdevant, who also manages diabetes, said. “The ignorance that I had was that I can’t have another one. So it’s not going to affect me. I didn’t want people to know.”

Sturdevant told the Mississippi Free Press that, at the time, he hoped his HIV diagnosis would “just go away.”

“I think Corey was on the same line of thinking,” Sturdevant said. “We didn’t want that rejection that we feared we would get from the family. And of course, with Corey being in this area, it was just something you didn’t want to deal with—the way people talked about folks living with HIV/AIDS.”

In response to Burnside’s negative experience with the specialist, Sturdevant pointed out that no two experiences with medical providers in the Delta are the same.

‘”You do what I tell you and we’ll get you back,'” Sturdevant recalled a nurse practitioner advising him at a Greenwood clinic during the lowest point in his journey living with HIV.

“I haven’t had any experience with those kinds of doctors. But I know some are ignorant and don’t know how to talk to people.”

HIV is now manageable, but the increased stigma associated with it can often be as deadly as the disease itself if left untreated. Sturdevant takes his role seriously as a mentor to Burnside and other young Black gay men.

“It’s not something that I planned,” Sturdevant said. “I told God that I didn’t want young men to grow up like I did without a dad and I wanted to make a difference.”

“Cedric spoke power into me,” Burnside said. “No matter what room I step in, I’m gonna make sure Cedric’s name walks along with me.”

“I see the fruit of my labor in these guys and how God continues to use me,” Sturdevant concluded. “I get tired. I keep saying I’m getting old, but I have to realize that I think they keep me young.”

“There’s no bridge I wouldn’t cross for Cedric,” Burnside said. “I can honestly say that and mean it: That’s my dad.”