We already tried that, and it didn’t work out so well for certain people. The small town was Money, Miss., population less than a hundred. Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was accused of whistling at a white woman.

They took care of their own all right—their white own.

Jason Aldean’s song has Nashville country music fighting it out over how “woke” they are. With lyrics like, “Try that in a small town. See how far ya make it down the road. Around here we take care of our own,” it’s easy to see why the gloves are off (especially if you watch the video).

Emmett Till made it to the bottom of the Tallahatchie River with a fan motor tied around his neck. That’s how far he got.

I know, the song is “art,” and art is supposed to activate the right brain, the one that doesn’t analyze and judge, but here are some left-brain questions: Which small town? And where? In what time of history? And who exactly is “our own?”

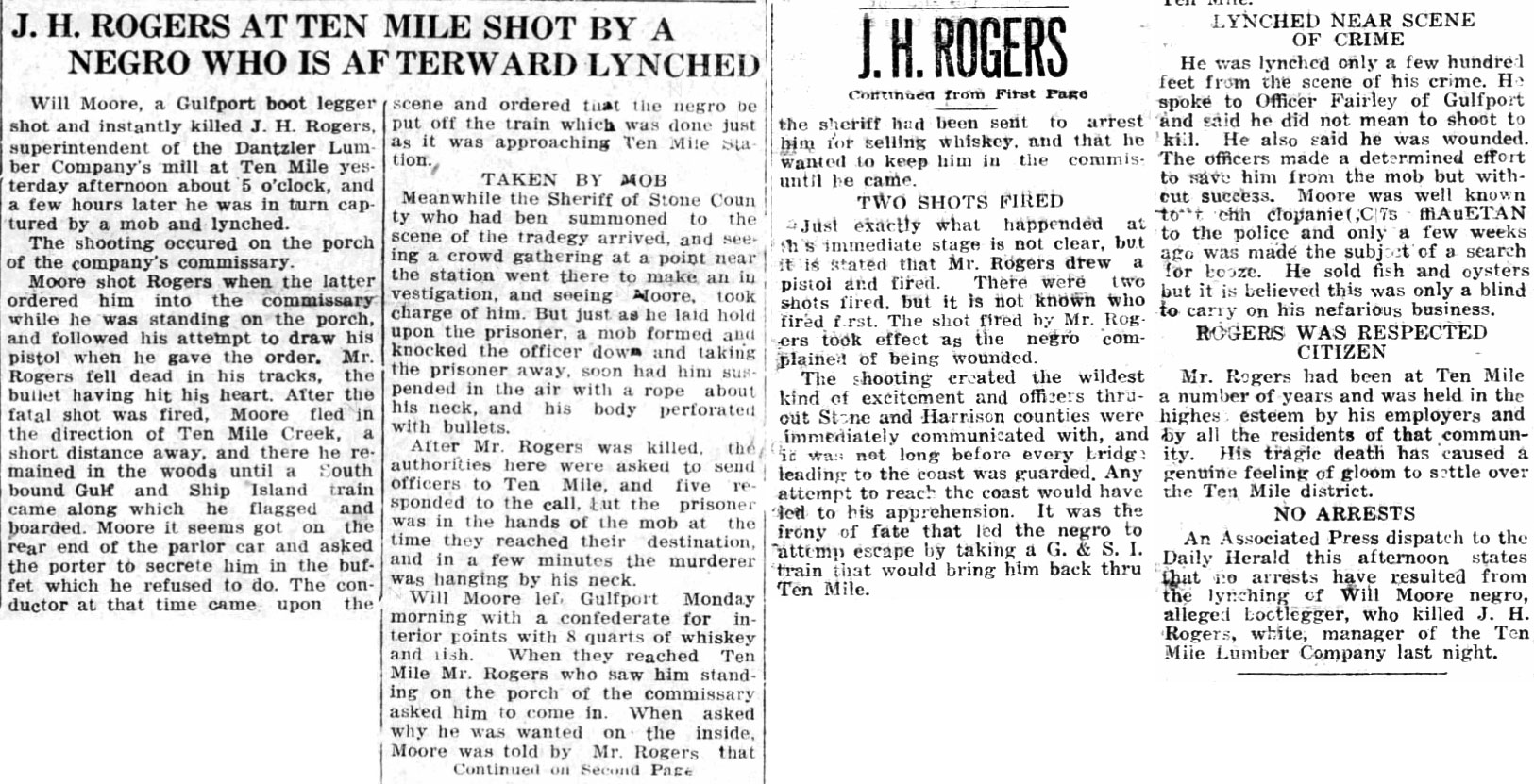

Emmett Till was murdered in 1955, a long time ago. But there’s a peculiar “Southern” tradition continuing here. Let’s look back, even longer ago, to May 21, 1919. A news report in the Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald found that “Will Moore, a Gulfport bootlegger, shot and instantly killed J.H. Rogers, superintendent of the Dantzler Lumber Company’s mill at Ten Mile, yesterday afternoon about 5 o’clock.” Shortly thereafter, a mob captured and lynched Moore.

In a commentary in the same paper, regular columnist Bostick “Crab” Breland opined that, with this lynching, “Stone County got the first stain on the clean pages of her history” (as it was a newly formed county). He went on to point out: “We know nothing of the facts in this particular case, nor the makeup of the mob that enacted the tragedy.”

Characterizing himself as someone “who looks beyond the excitement of the hour (and) thinks below the surface,” he found the incident “sickening.” Two people were dead, yes, but in the process, “that spirit of violence that has been planted in the minds and hearts of the boys, and watered with blood, still smolders and may blaze up after many days,” Breland lamented. Wise words indeed, especially for a century ago.

The Spirit of Violence Blazes On

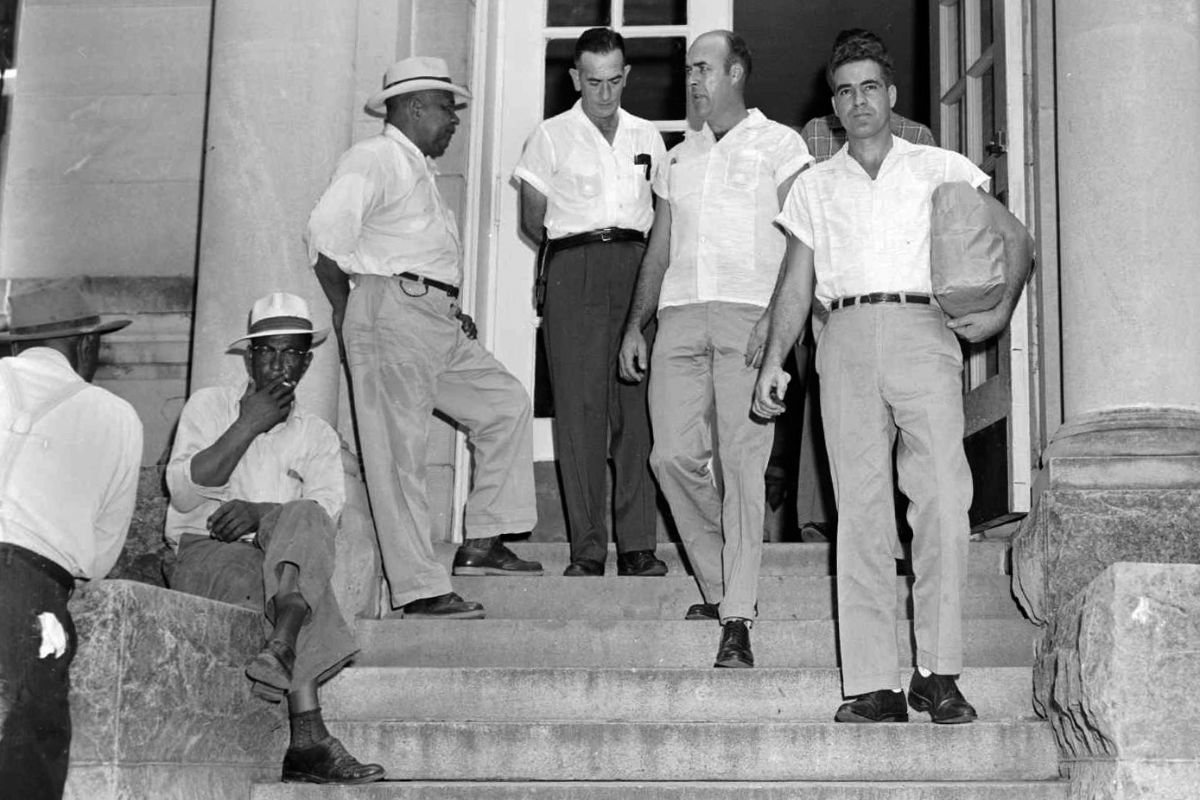

Decades later, in 2023, the assailants, calling themselves the “Goon Squad,” were five members of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department and one member of the Richland (population 6,900) Police Department. The victims were Michael Jenkins and Terrell Parker.

Mississippi Free Press’ and other outlets have reported for months that the officers broke down Parker’s door without a warrant, and threatened the two Black men with rape, and both beat and tased them. One officer forced his gun into Jenkins’ mouth and fired, shattering his jaw. During this torture, the officers called the two “n—er” and “monkey,” and told them “to stay out of Rankin County and ‘go back to Jackson or to ‘their side’ of the Pearl River.’” At one point, one of the officers attempted to “waterboard” them with milk, alcohol and chocolate syrup, before pouring cooking grease on Parker’s head. They’ve all now been charged and pleaded guilty.

Again I ask, which small town? And where was it? And when did who “take care of ‘their own’?”

Jason Aldean, you’ve made a pile of money with your song. This song won your first number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 list, and I guess the writers got their fair share, too: Kurt Allison, Tully Kennedy, Kelley Lovelace and Neil Thrasher.

Again, I know it’s “art,” but when you have people dancing to the tune of “Around here we take care of our own,” and you are praising those “good ol’ boys, raised up right” with guns “my granddad gave me,” you know somebody’s gonna get badly hurt. So, I gotta ask: Do you want to be a party to that? Do you even care?

As for consumers of popular music: Do we really want those with the meanest looks, the loudest voices and the most guns to be running things? Is that the world we want to live in? I don’t think so. That flag Aldean sings about in the second verse does not stand for vigilante justice. It stands for the rule of law.

This column was originally published in Pine Belt News. Read the original story here.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.