In America’s past, white nationalism had unprecedented control over the country’s culture. Many individuals would argue today that this cultural behavior no longer exists, but racism has evolved and adapted to modern-day America. White nationalism has an origin story, and it is important to learn its roots.

Many authors have written on this subject and its racist effects. As more books on such sensitive subjects come out, many resist learning true Black history. Learning about America’s past failures and realizing its continued legacy in white nationalism invokes fear in the minds of anti-Critical Race Theory advocates. Nikole-Hannah Jones wrote such a book, “The 1619 Project,” an educational achievement that was adapted into a Hulu TV series. Jones’ series and book force America’s white culture to revisit the origins of this land through the eyes of the enslaved.

There is great difficulty in looking at history from more than one perspective, especially when that perspective is outside one’s comfort zone. This difficulty has been ingrained in many white Americans due to our nation’s educational system spraying confetti and memorializing its forefathers with the greatest esteem. America loves to indoctrinate its students with patriotism and adoration for the country’s personal selection of the individuals who qualify as the greatest of patriots. This is the exact reason “The 1619 Project” receives resistance due to its hard-core critique of America’s selection of so-called patriots.

“The 1619 Project” shines a much-needed light on the enslaved Africans who were forced over to Jamestown, Va., centuries ago by men long celebrated for founding this nation. This perspective causes massive cognitive dissonance for the roots of American history—these white forefathers are not heroes, but colonizers. One should question the alias of America being described as “the New World” from past descriptions. This land and its indigenous communities were not new. They existed prior to the arrival of the first supply of colonists in 1607.

My Ancestry in White Nationalism

One of the white men who came over in the first supply was Robert Beheathland. He was listed as a gentleman in Capt. John Smith’s book, “The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England and the Summer Isles” where he mentions him as a first planter. Beheathland, my earliest Virginian ancestor, accompanied Smith twice to visit members of the Powhatan trlibe. Beheathland also was with Smith during the first Christmas among the Indigenous. Throughout Smith’s book he refers to the Indigenous tribes as “savages.” This derogatory word reiterates the discriminatory ideology forced upon anyone not white.

On the second supply, a Virginia leader named Capt. Thomas Graves would come over on the ship Mary and Margaret in 1608. I am a descendant of Graves through his daughter Verlinda Graves who married William Stone—the first protestant Maryland governor. This prominent white man, a stockholder in the Virginia Company of London, would also serve as a representative in the first general assembly held on July 30, 1619.

Gov. Yeardley appointed Graves in a letter written after April 1619 to lead the people of Smythe’s Hundred. His leadership positions illustrate his impact on his community since African slavery continued in the Virginia Colony. Although no documentation shows that Graves owned enslaved Africans himself, his participation in the colonization of Virginia and racist effects are evident—more Africans were forcefully imported and enslaved as the Virginia Colony continued to grow. There is no mention of his involvement in preventing the importation or enslavement of Africans.

This date correlates to “The 1619 Project” because the enslaved Africans arrived roughly a month after the first general assembly. Jones’ work puts a magnifying glass on the first Africans forced over to Jamestown, Va. Traditionally, enslaved persons of color had not received such attention in the educational area. The amount of resistance, such as today’s banning of books and curriculums, reiterates a valid point from “The 1619 Project”—the fear of America’s role in African enslavement since its genesis. For this reason, the first general assembly set the foundational political structure for America.

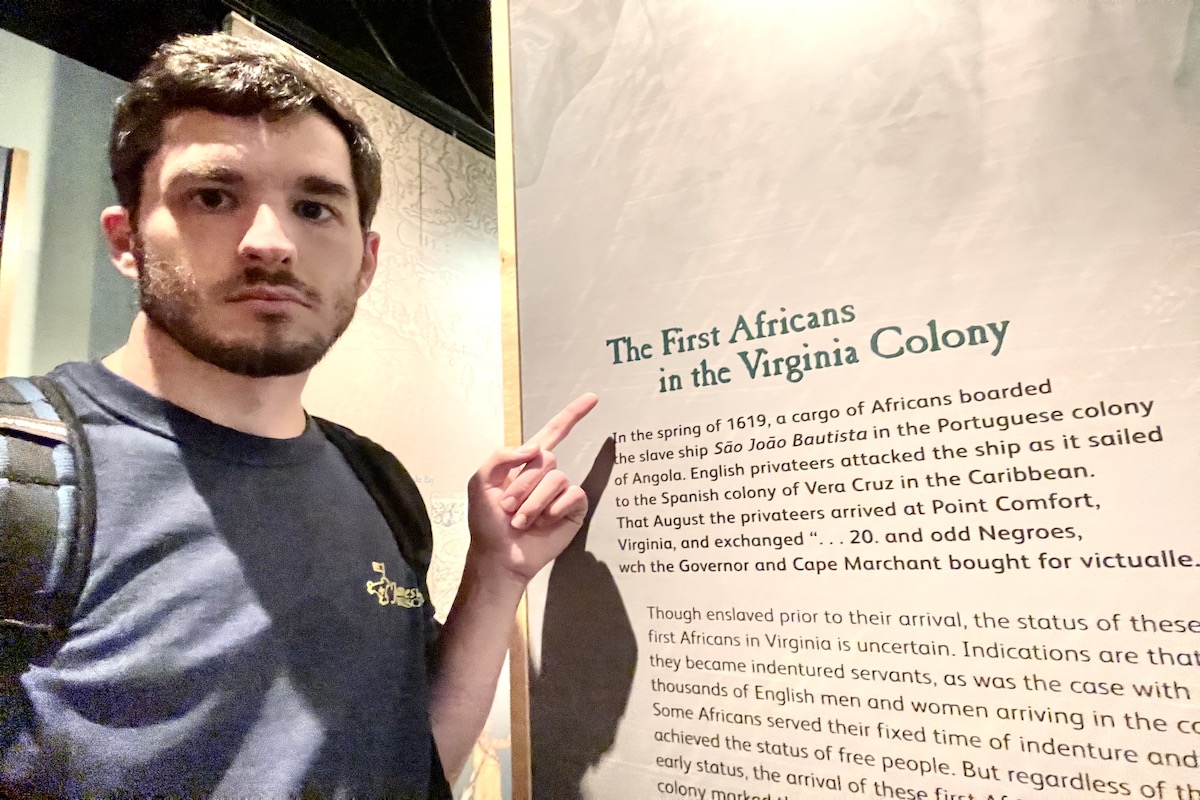

Arrival of ‘20 Odd Africans’ to Jamestown in 1619

The continued involvement in African enslavement connects to the first general assembly’s policies: “Be it further ordained by this General Assembly, and we die by these presents enacted, that all Contracts made in England between the Owners of lande, and their Tenants and Servants which they shall sende hither, may be caused to be duly performed, and that the offenders be punished as the Governor and Council of Estate shall think just and convenient.” The relationship has been established between servant and owner in the first enacted legislative policies of Virginia prior to the arrival of the “20 Odd” Africans.

I recently visited the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn., and during the tour, I saw human figures in bondage sitting down while sound effects of whipping played repeatedly. This visual imagery and educational aid also explained the Middle Passage and the early 1600s of colonial Virginia. It reminded me of Jones and her work on Black history.

There, I saw a painting of a white man forcibly commanding Africans in the exhibit. I was reminded of my 10-time, great-grandfather Captain Thomas Graves. He did nothing to prevent the global infection of slavery from inserting its DNA into colonial America.

The effects of African slavery are seen in 1619 and one of its biggest reflections are from the Civil War. This country-wide battle over the enslavement of African Americans could have been prevented from the beginning.

Again, my genealogical history comes into play. My two times great-grand aunt, Mary Tabb Bolling, is the daughter-in-law of Robert E. Lee—she married his son, Congressman William Henry Fitzhugh Lee. Fitzhugh Lee was a Major General in the Confederate Army, Prisoner of War and Congressman. I am a member of the Descendants of the Enslaved at Mount Vernon to support removing the name “Robert E. Lee” from Arlington House, currently known as the nation’s memorial to the Confederate, slave-owning general, to Arlington National Historic Site.

The removal of statues, names, symbols and flags are all continuous efforts to remove a racist legacy that originated in 1619. “The 1619 Project” critiques the roots of African slavery in America and its educational value is significant. Just as I can trace my ancestry back to Captain Thomas Graves, likewise, other white people should trace their ancestry of white nationalism to gain a broader understanding of themselves.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Journalism and Education Group, the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.