STARKVILLE, Miss.— Brush Arbor Cemetery, also known as the Starkville Colored Cemetery, is hidden among trees in a plot of land between the yellow shack that holds Scooter’s Records and the three-story building with Commodore Bob’s restaurant and liquor store on University Drive in Starkville. It is across the street from the far-better-maintained Odd Fellows Cemetery, where ornate stones and statues honor prominent white Starkvillians from the past.

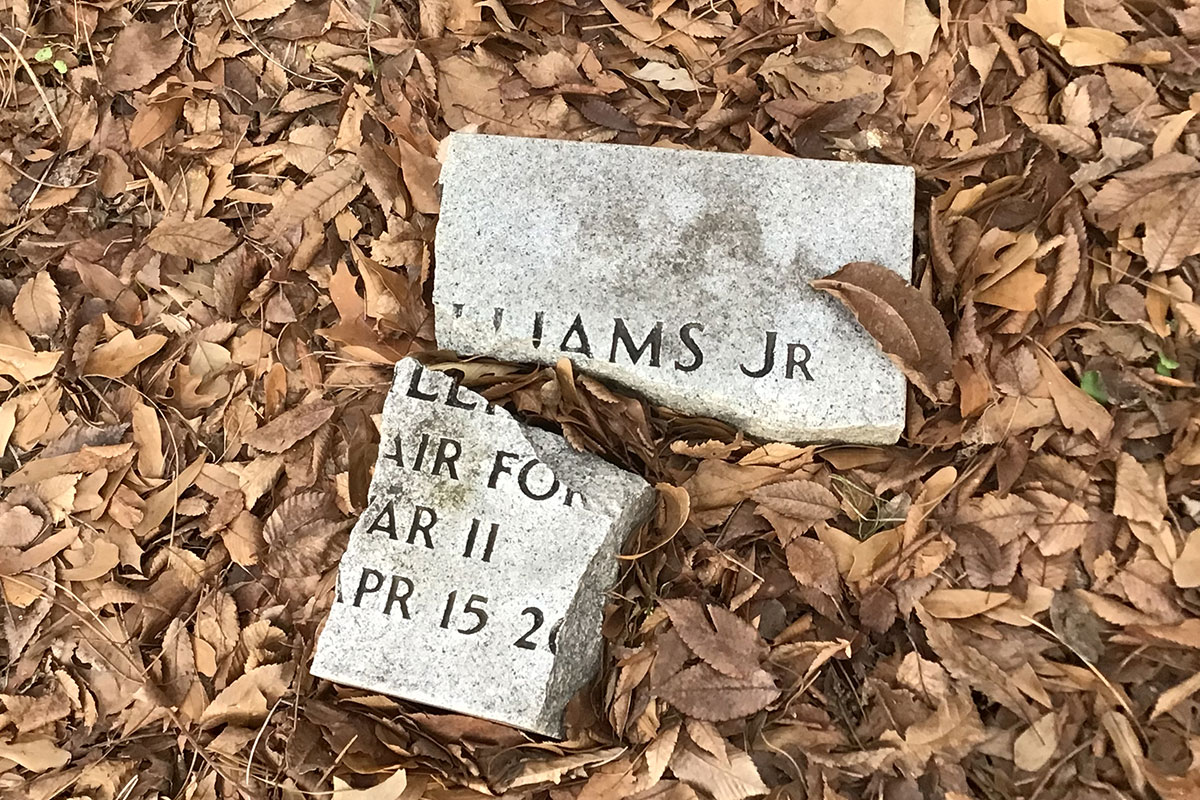

In Brush Arbor, about 33 tombstones dated from 1882 to 1920 sit in patches of grass and dirt behind a bench and a Starkville land marker, erected in 2014, that details a timeline of the unfenced cemetery. More people could be buried at the location in unmarked graves, the sign says, considering noticeable indentations in the ground. The sign indicates no dog-walking in the cemetery, which has long been popular for that activity, but the Mississippi Free Press has observed owners allowing dogs to run loose among the remaining tombstones since the sign went up.

The cemetery’s full history is largely unknown, but Dr. Jordan Lynton Cox, an assistant professor of cultural anthropology and Middle Eastern studies at Mississippi State University, is leading a cohort of young researchers as they uncover the roots of the Brush Arbor Cemetery.

“Our work is vitally grounded in not only community engagement but decolonial practices and cultural heritage preservation,” Taia Bush, a senior at Carleton College, told the Mississippi Free Press on July 16.

Ten students from across the country came to Starkville for five weeks this summer to research the lives of those buried in the cemetery through the Brush Arbor Community-Engaged Field Program. The National Endowment for Humanities funded the three-year program, now in its first year.

‘Changed Purpose’

Joseph B. Earle bought land in Mississippi and Alabama during the 1830s and 1840s. One of his purchases included the area where the cemetery now resides close to Needmore, a historic Black community. The City of Starkville does not have any other records for this time.

The cohort of students learned that African American Baptists and Griffith Chapel Methodists formed Union Church on that land in 1867 to fellowship and worship outside the many all-white churches in the area at the time. Union Church disbanded in 1869, and the churches separated into Griffith Chapel and Second Baptist Church.

The City’s records resume in 1925 when the Starkville Colored Cemetery was on an official Starkville map.

R.C. Morris wrote about Union Church in a 1937 history of Oktibbeha County for the Works Progress Administration using documents and interviews with locals. He did not mention how he uncovered the story behind the name “Brush Arbor,” the historic-marker sign said.

Cox said the team refers to the cemetery as both Brush Arbor and the Starkville Colored Cemetery because they do not know for certain whether the site was a brush arbor, which is a “very particular kind of meeting place.”

Formerly enslaved and freedmen around Civil War time would gather among brush in the woods to practice their religious beliefs and African traditions, which were not accepted in white society, Cox explained.

“(The land) actually seems to have changed purpose over time,” she added.

The professor said the city previously called the space the Starkville Colored Cemetery before renaming it Brush Arbor Cemetery. City Clerk Lesa Hardin said she had not found any documentation to confirm when that happened.

“The space on all records that we have found call it the Starkville Colored Cemetery,” Cox said.

‘Long-term Preservation’

In 2021, Cassidy Rayburn, then a master’s student at MSU, was doing her master’s thesis on Brush Arbor Cemetery when Cox was in her first year at the university.

“I went with another faculty member to look at the cemetery, and I was just kind of astounded by how much decay and how much it deteriorated despite how important this place was,” Cox told the Mississippi Free Press. “… I was like, ‘We really need to do something to promote the long-term preservation of this place.’”

Cox and fellow faculty members applied for the National Endowment for Humanities grant and used the money to create a program that taught budding anthropologists real-life skills while preserving the history of the cemetery. The grant funds the research for three years.

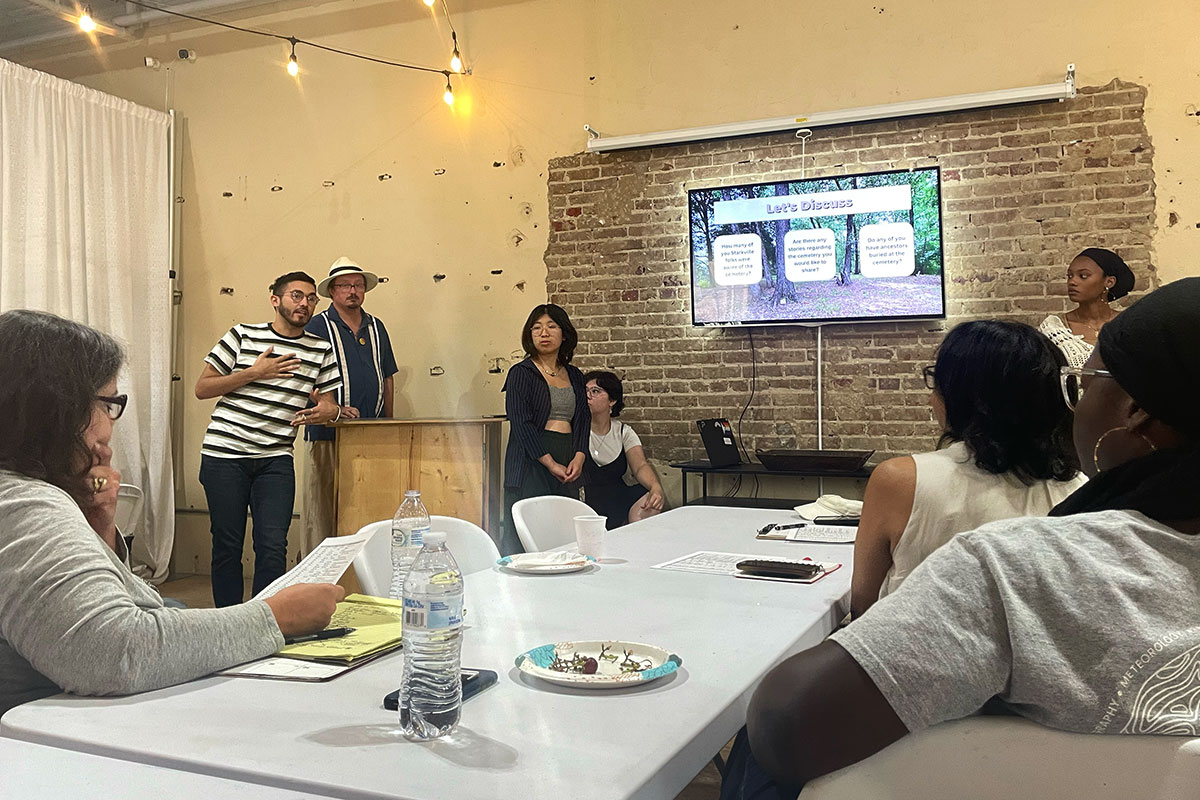

The professor and the students held a community-dialogue event on July 16 to introduce themselves and their research to residents. About 15 people sat at the tables in the back of Dunkington in downtown Starkville to hear their presentation.

This summer, the students researched the origin of the cemetery and the lives of the deceased by interviewing residents and looking at city records. They encouraged Starkville natives to look through their ancestry records to see if they are related to those buried at Brush Arbor.

“We cannot do this work without you,” Taia Bush said to those gathered at Dunkington.

A major in African studies, anthropology and sociology, she wanted to use what she has learned in the classroom out in the field.

“So for me, this is really just a chance to give back to those that allow me to be there and to honor the most important parts of our history,” Bush said.

Next year, a new cohort of students will raise awareness for the cemetery with national organizations for long-term preservation. They will do ground-penetrating radar and lidar (light detection and ranging) in the cemetery to detect what lies underground without disturbing remains.

Ground-penetrating radar uses radio waves to look underground and detect materials like concrete, metal, asphalt, plastic and PVC. Light detection and ranging, or lidar, uses light pulses to create a three-dimensional image of the subsurface of the earth.

“So between GPR and lidar, we should be able to have a more capacious understanding of who’s buried there, even without markers,” Cox said.

In the program’s third year, another cohort will educate the public about Brush Arbor Cemetery by speaking in schools, talking with politicians and creating a website.

‘Trace Their Origins’

At the community event on July 16, students discussed some of the deceased who are buried in the cemetery, like Dinah Isaacs, who had an obituary in the Starkville Daily News on May 5, 1911.

“Dinah Isaacs (colored) aged 62 years died on May 1st, and buried the following day in the colored peoples’ cemetery. … She was respected by her white friends for her many good traits of character,” the obituary said.

George Washington Chiles was enslaved when he came to Starkville in the late 1840s. He was freed after the Civil War ended, became a mail carrier and Board of Education member and helped create the Second Baptist Church. Chiles is buried in Brush Arbor Cemetery, and his grave marker says he lived from 1840 to 1929.

His brother, Benjamin Chiles, was one of the first Black people to hold elected office in Oktibbeha County, and he served in the Mississippi Legislature from 1874 to 1878, elected during Reconstruction before Mississippi white supremacists slammed the door on state office for Black Mississippians for decades.

“A lot of people in Starkville and elsewhere can trace their origins to this site,” Carlos Montes, a recent anthropology graduate from the University of Pennsylvania, said.

Cox and the students in the cohort want to raise awareness in the community so that the cemetery is cemented in history.

“You don’t have to be a descendant from the people buried in the cemetery to be an active part of its preservation and longevity,” Cox encouraged.

People with additional information about the Brush Arbor Cemetery and those buried at the location that they would like to share with the research team may contact Jordan Lynton Cox by email at jlynton@anthro.msstate.edu.