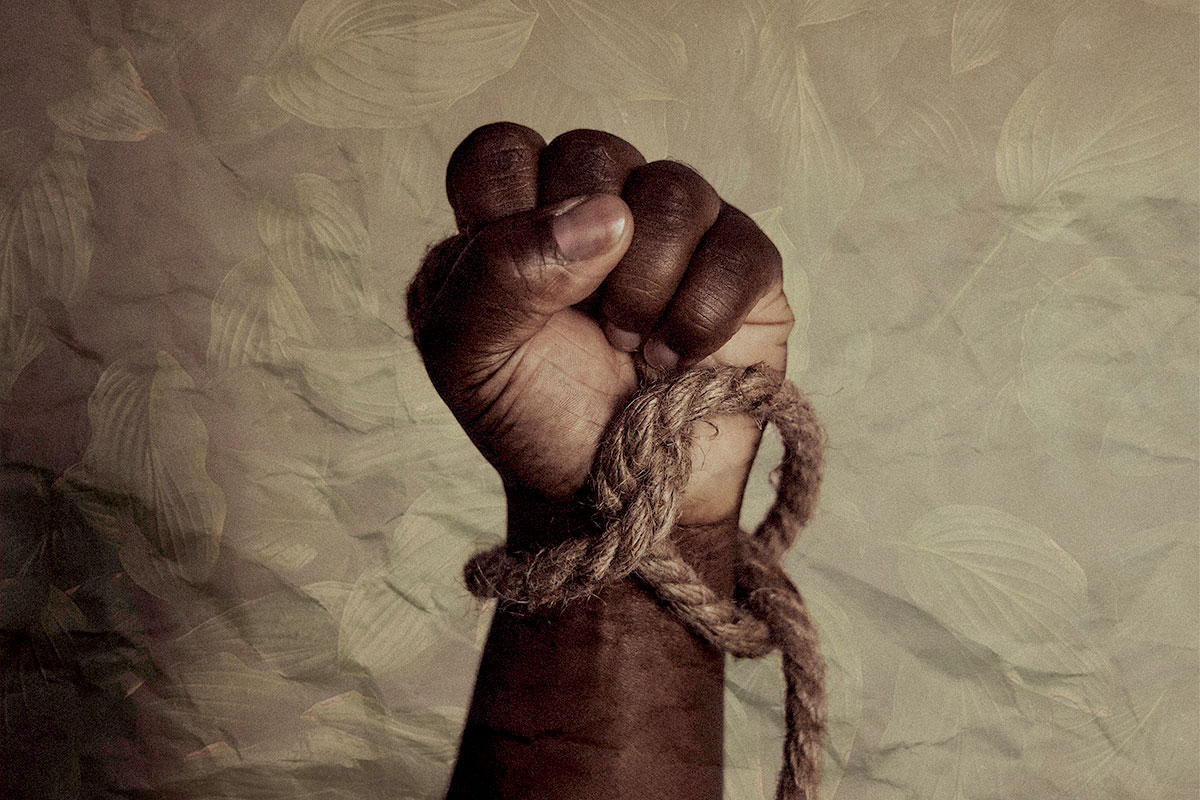

During the transatlantic slave trade, Black bodies were kidnapped from their homes, transported inhumanely and then treated worse than animals. Black men, women, and children were sold into chattel slavery and remained in that cruel institution for nearly 250 years, spanning 10 generations.

It took a civil war in 1861, in which America defended itself against a rebellion to divide the Union (a unified nation), to address slavery. During this war, the nation fought to keep 11 of its 48 states from dividing the union.

The United States fought to put down a rebellion that sought to legally dehumanize an entire race of people for personal gain in riches and status for generations to come. The Confederacy fought to arrogantly claim superiority over an entire people because of the color of their skin.

This ever-present reality, using “skin color as a differentiator,” affects every person of color, especially Black people. I am a Black man, and every other person of color is embodied in me. We all share the experience of racism based on the color of our skin, no matter the shade. We must understand that injustice or justice toward anyone is also the reality for all sharing the same distinction and has a relevant impact on the entire human race.

So here we are again, in 2023, propelled into a position where the discussion, the real talk, must be done. But it must be more productive than talks of the past. Let’s look at what this nation has encountered in the comprehensive battle to live out the tenets of our very own Constitution.

What History Has Taught Us

History should teach us to be better in the future, but it seems like we have learned nothing.

The Civil War set me, the Black man, free legally, resulting in an Emancipation Proclamation, which eventually led to the 13th Amendment of the Constitution in 1865. But I soon realized that I was not really free in America. Black people were “set free” and yet remained in bondage to every sort of scheme rigged in a system designed to continuously oppress us.

One freedman, Houston Hartsfield Holloway, wrote, “For we colored people did not know how to be free and the white people did not know how to have a free colored person about them.” So, it was my fate to be free theoretically, while simultaneously living a disenfranchised life, one absent of true freedom.

At this point in history, after the Civil War ended, I was subjected to Black Codes, which robbed me of my right to be American, although thousands of lives were sacrificed for my freedom. The rebellion of the Confederacy had been put down, but the training to be subservient—training whites imposed on me—continued. It was legitimized with judicial outcomes such as Plessy v. Ferguson, which said that it’s perfectly acceptable to be “separate but equal.”

By the time white lawmakers embraced Jim Crow laws—like in the 1890 Mississippi Constitution—I was conditioned into this idea of “separate but equal”, and would be constantly reminded with “whites only” water fountains and restrooms and “coloreds only” outside service windows positioned at the back of establishments, like pushing food outside to dogs not fit to come sit inside. All of these rules were designed to make me know that I do not matter.

At multiple points after Emancipation, legislation was passed to acknowledge me as fully American: in 1865 the 13th amendment freed me; the 14th amendment made me a citizen in 1868; and in 1870, the 15th amendment gave me the right to vote. And yet with all these changes, I still wasn’t an equal partaker of freedom in America.

For more than 250 years, it was against the law for me to learn how to read, and yet I was subjected to a bogus literacy test to determine if I should really be allowed to exercise my 15th Amendment right to vote. White hate groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, imposed intimidation with literacy tests and poll taxes. All of this was weaponized to prevent me from exercising my right as an American citizen, although a constitutional amendment guaranteed it.

I struggled, fought and died to gain the right to be acknowledged as fully American. I fought and died seeking to exercise my constitutional right to be an equal partaker of freedom in America and to have my civil rights recognized in more than just words. There were some white folks who fought and died for this cause, too, and I acknowledge their sacrifice. I also fought in every major war, including the American Revolutionary War, to make and keep America free. And yet I cannot equally partake of freedom in America as I am still shackled because of the color of my skin.

There are many that would say, “You have all the rights that I have,” yet in so many cases I have been put to death, for which a white man under the same circumstances would have been able to go home to dinner with his wife and children. This is the ultimate oppression—to deprive me of life because of the color of my skin. This is the answer America has so often given me. This is America’s reply to my constant demand for true liberation in this nation.

This continuous disenfranchisement solely because I am a man of color in America is wholly inadequate and still unacceptable.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Journalism and Education Group, the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.