The first place I met Hodding Carter III was far from Mississippi, the state we have in common. It was in New York City at a black-tie journalism gathering in late 2000 at the Waldorf-Astoria Grand Ballroom, an annual event considered an “A-list media gathering.” I was there as a grad student from the Columbia Journalism School, and my opinion-writing professor, the great Victor Navasky, had assigned Hodding as a dinner guest for me to track down and talk to about this “media elite” event—you know, we’re both from Mississippi and whatnot.

As the long-time editor and publisher of The Nation, a journal of opinion that understands the necessity to critique and thus improve the journalism industry from within, Victor had assigned our small class to approach attendees at the posh event of journalism stars, executives, PR professionals and big funders. We were to ask them pointed questions about the contradiction, and potential irony, between such a corporate-backed awards celebration to raise funds for journalists imprisoned and endangered around the world, including in what many folks in the room might consider “third world” countries.

You know, it was like so many fundraisers: exclusive rooms full of tuxes, expensive dresses and martinis with de facto velvet and geographic ropes between the revelers and those they’re helping. This odd paradigm raises needed funds, no doubt, but is cringey, and that’s especially true when journalism organizations are checking names at the door before allowing entry. We exist, after all, to protect and build up democracy and equitable access, or at least I think that should be our mission.

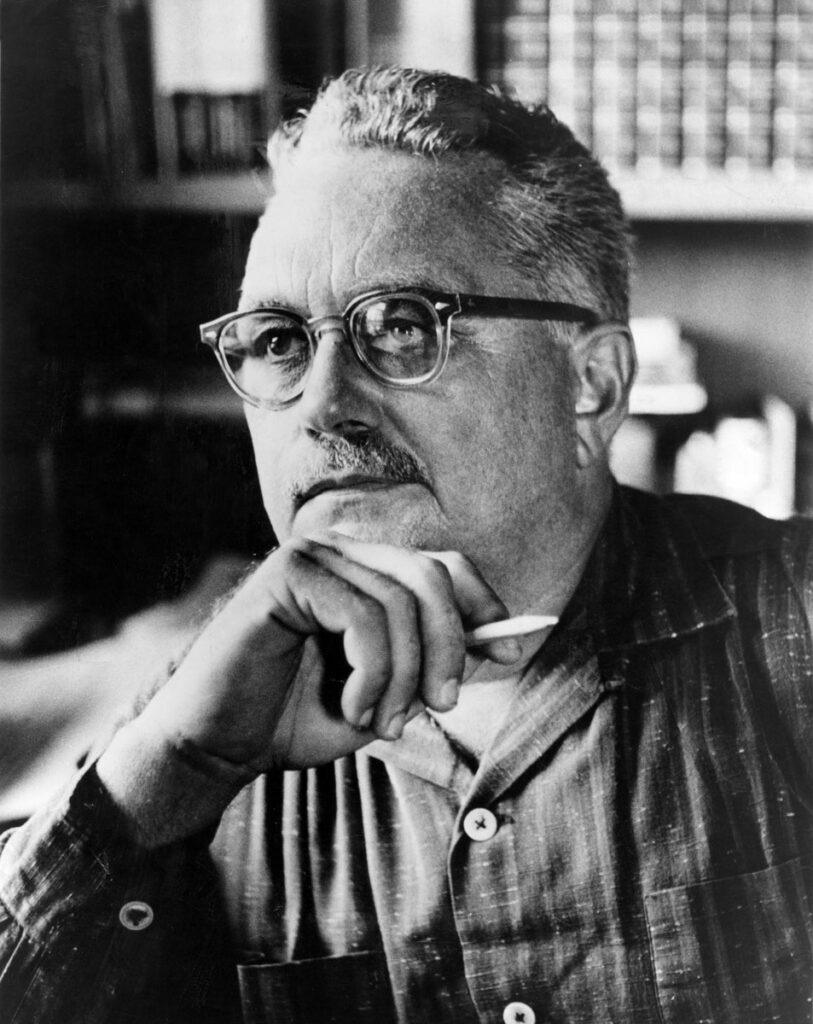

Still, I think of the shiny shindig now as my meeting with Hodding meant to happen. I already admired him, and his father Hodding Carter Jr., for finding the fortitude to stand up to racism and business-suit bullies in Mississippi when they ran the then-much-better Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville on the western edge of the Mississippi Delta. So I was admittedly a touch nervous about approaching him. He was a long-time journalism celebrity, the Knight Foundation top executive then and a former State Department spokesman during trying times, as well as a journalist, editor and book author like his famous father.

At the Waldorf, I meandered up to Hodding’s table near the front and crouched down next to his chair in my long, silver dress and introduced myself. With other women attendees mostly in sleek black cocktail dresses, I was working hard not to feel overdressed in my gown more appropriate for Tougaloo College’s Two Rivers Gala (which I’d indeed wear it to several years later after my first meeting with Hodding propelled me into Mississippi media, not to jump ahead). But, hey, I am southern, so might as well pretend to be the belle of the ball for the night.

Hodding, looking ever-handsome in his tux with his slightly crumpled salt-and-pepper hair, leaned toward me to hear my prepared questions after I told him I was from Neshoba County (which raised his eyebrows and piqued his interest). He understood the job immediately, and his inner showman didn’t hesitate to launch into a mildly mocking soliloquy about the “self-reflecting” glory of the media elite. As the Alex Donner orchestra provided the background music, Hodding mixed in rowdy cuss words, which as a southerner put me immediately at ease. I scribbled in my reporter’s notebook as he gave me the juice I needed.

Then Hodding stopped performing on the record and handed me his business card, saying words to this effect: “Stay in touch and come see me if you’re ever in Miami. We can talk more about that *BLEEPING* state you grew up in.”

I’ve been thinking about what happened next between us since Hodding III died on May 11, 2023, and how his choices, courage and advice both jump-started and inspired my own work in Mississippi for the last two decades. Let’s rewind, first, to where that righteous rebellion came from.

Business Suits By Day, Hoods By Night

One of my recurring images when someone mentions the Carter family is the reaction of Hodding III’s dad, Hodding Jr., when he and wife Betty were having dinner with their son Philip and his new wife in New Orleans in 1961. Suddenly, a car backfired outside, sounding like a shotgun blast. “Hit the floor! Get your gun!” Hodding Jr. yelled, as recounted in Ann Waldron’s biography of him.

It was the 1960s, and sudden booms easily could’ve been bullets aimed at a family that both interacted with Washington County’s elite—poet, writer, lawyer and plantation heir William Alexander Percy supported his newspaper—and who by then were challenging those pushing racist apartheid and violence in Mississippi. The father won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1946 column calling out white Americans for racist treatment of Japanese Americans, including U.S. soldiers.

“A lot of people will begin saying, as soon as these boys take off their uniforms, that ‘a Jap is a Jap,’ and that the Nisei deserve no consideration,” the father had written.

U.S. Sen. Theodore Bilbo, who was a race extremist even by Mississippi standards then, was furious at the “Nisei” column: “No self-respecting Southern white man would accept a prize given by a bunch of n***er-loving, Yankeefied Communists for editorials advocating the mongrelization of the races.”

Infuriating Bilbo over race is a mark of honor I can fully appreciate, even if Hodding the father did not progress on racism and integration in his 65 years as far as his oldest son would accomplish in his 88 years, picking up his father’s torch and growing the flames.

Still, the father’s eventual defiance of his own learned beliefs, including calls for “gradualism” rather than immediate change on behalf of Black Americans, was still revolutionary for a white man in Mississippi in those times, if imperfect. Or, more accurately, as his son would write years later, his father was “evolutionary” rather than revolutionary.

“He never became what any self-respecting Northern liberal would have called an integrationist,” Hodding III wrote about his dad in a Nieman fellow essay. “He spoke for the South in scores of articles that alternated their loving depiction of Southern virtues with condemnation of its most blatant and inhuman excesses. He spoke for change, but organic and slow rather than legalistic and fast. Slow or fast, it was too much for the white majority.”

The father supported better education for Black students, writing that it was “the reconstruction to give us a future,” even as his own views went through their own reconstruction, leading to a next generation of children, like Hodding III, who were less patient with gradual change.

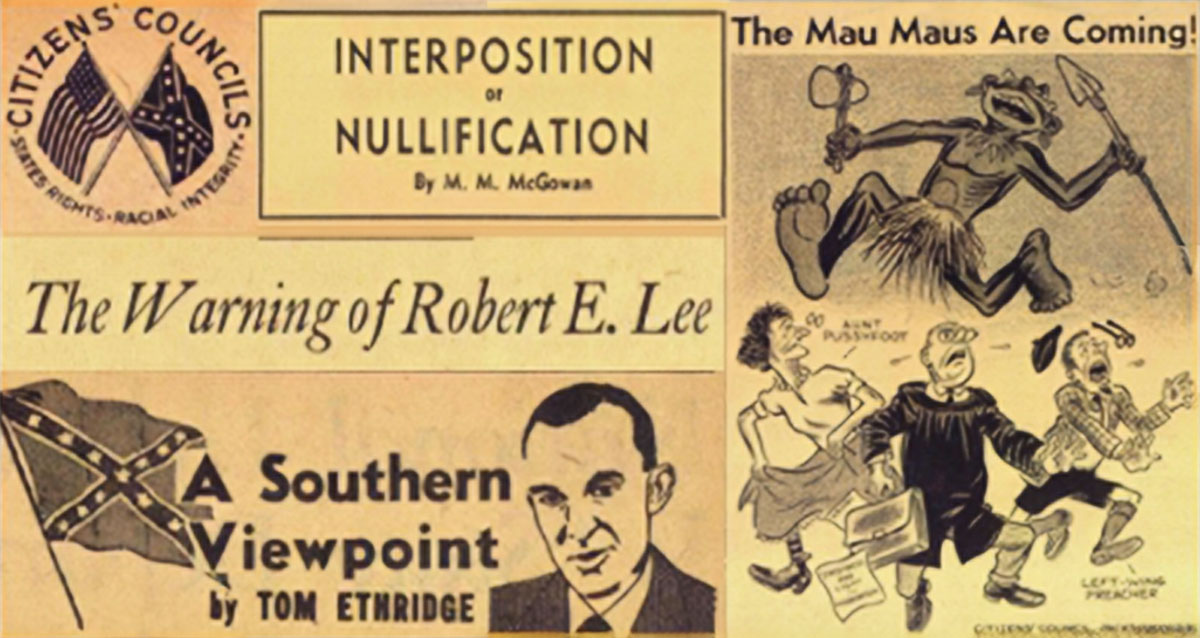

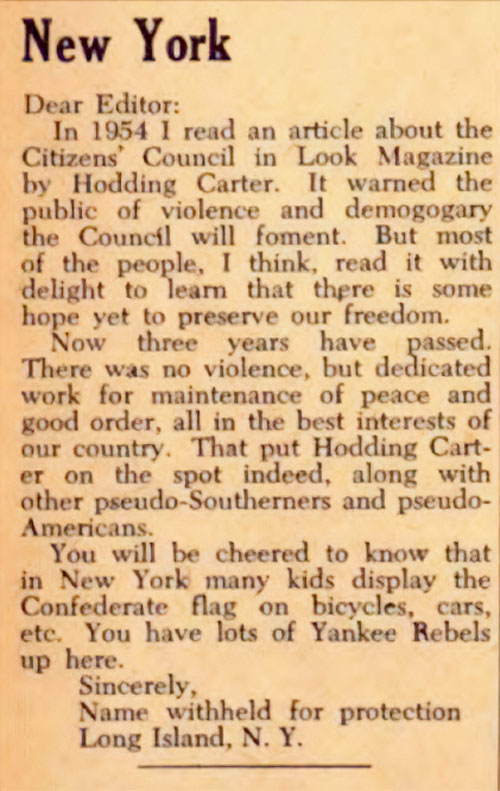

Hodding Jr.’s own admonitions of racists, and especially his challenge of its upper-crust progenitors, would bring continual threats of violence and boycotts from the racist Citizens Council, which both Hoddings exposed, poked, and turned a middle finger toward in their newspaper and national publications continually. Council members pushed back in their own Citizens Council newspaper, mailed across the U.S., and through newspapers across Mississippi, including The Clarion-Ledger and the Jackson Daily News, both overtly racist organs then run by Council colleagues.

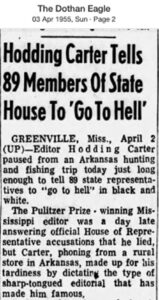

Hodding Jr. first dubbed the business-suited terrorist/boycott/propaganda machine the “uptown Ku Klux Klan” in Look magazine in 1955—twice—leading to official censure by the Mississippi Legislature. His son later wrote that the floodgates of white hate then fully opened on them: “the war was joined for real.”

To be honest, the Citizens Council wasn’t all that different from the KKK, and many white men (like Byron de la Beckwith who killed Medgar Evers here in Jackson) were members of both: business suits by day, hoods by night. Some were also members of Americans for the Preservation of the White Race, founded near Natchez and run in Mississippi by prominent citizens and editors (like of the Meadville, Miss., newspaper then) who helped gather up legal fees for arrested white terrorists. It was a tight web of resistance to integration by any means necessary.

In fact, members of the Citizens Council even got together in courthouses and private homes across Mississippi to vote to help reactivate the Klan as the violent enforcers of their desire for full segregation of society. The Hederman-family-run Clarion-Ledger and Jackson Daily News worked hand-in-glove with Council leaders as their publicity arms, even running large special sections to support their rabid resistance toward integration and continually promoting resistance to school integration.

The Carters didn’t back down, though. On Nov. 12, 1961, the month after I was born into a state where most newspapers continually frothed up racist fury to help boil it into violence, Hodding III wrote a piece for the New York Times Magazine about the Uptown Klan. He headlined it “Citadel of the Citizens Council,” in which he made it clear that, in Mississippi, “the diehard white supremacists are firmly in control.” Nearly three years earlier, in 1959, the son had also written a whole damn book about how the Citizens Council wanted to destroy the Carter family for their insolence. (The University Press has now published an exciting, updated version of “The South Strikes Back.”)

Scraping, Scratching and Dodging Boycotts

When I was at Columbia in the last couple years of the millennium, I’d picked up a used copy of Ann Waldron’s 1993 biography “Reconstruction of a Racist” about Hodding Jr., a white editor and entrepreneur who had raised enough hell that the family could easily assume the devil was firing through the front window. But they had stayed the course at the Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville with Hodding III taking the reins as editor in 1961.

After Hodding Jr.’s death in 1972, the paper continued until wife Betty sold it in 1980 because much of the family had left Mississippi, and she couldn’t afford a new $5-million press, Waldron wrote. Their selling and leaving used to bother me as a younger Mississippian hankering for journalism to finally help save this damn state I love, but now I get it. They’d done their time. They’d tried. They left nothing in the road. It was someone else’s turn.

Hodding III then had a storied national career as an author and media personality, as well as a storybook and public romance and marriage to his second wife, the badass human-rights activist Patricia “Patt” Derian, not exactly a gradualist for needed change by any standard. She preceded him in death in 2016, and he married former reporter and author Patricia O’Brien late in life in 2019, proving again that it’s never too late for a life filled with passion and romance.

The stories about the Carters in Waldron’s biography, which I was told that some family members did not fully appreciate for their own reasons, had a profound impact on me when I picked it up in grad school. In fact, Free Press journalism might not exist today in Mississippi had it not been for the Hodding Carter family.

For one thing, the story of Hodding Jr. and wife Betty scraping, scratching and dodging boycotts to succeed at journalism challenging the status quo and the old ways in Mississippi was inspiring as hell. My grad-school tenure and work were already making me want to return to Mississippi to report here for the first time—which I’d believed until then would never happen.

When I actually moved back to Mississippi (temporarily, we thought) soon after graduating in June 2001, the desire create a new kind of journalism here turned into starting the Jackson Free Press with my life partner Todd Stauffer in fall 2002. That brought not-dissimilar experiences to those of Hodding Jr. and Betty along the way.

Throughout the JFP’s tenure, I thought of the tenacity of the Hoddings and Betty as stubborn inspiration—and we kept that newspaper alive until last year, two years into the pandemic, through pure gumption, as well as skipping our own paychecks from time to time rather than ever laying anyone off.

And no, I can’t deny my desire for the sense of adventure the Carter family seemed to share as they made an impact on our state and nation. I can say now that running the Free Press in Mississippi since 2001 has been nothing if not a Carteresque roller coaster of an adventure down to threats, smears and attempted boycotts of JFP advertisers. And more than a few run-ins with racists, liars and misogynists.

At least the Hoddings were men talking back to power. They had the Citizens Council; I had the North Jackson Angry Men’s Club and political operatives accusing me of every damn false thing and putting my name into anonymous mailers and even journalists spreading demonstrably fictitious smears about me without ever bothering to check them out. I’ve toughened my skin by facing down men, especially, of every political stripe simply flummoxed and furious that I dare to challenge how they represent Mississippi, do their public jobs and who they leave out.

How dare I not ask their permission first? Who do I think I am?

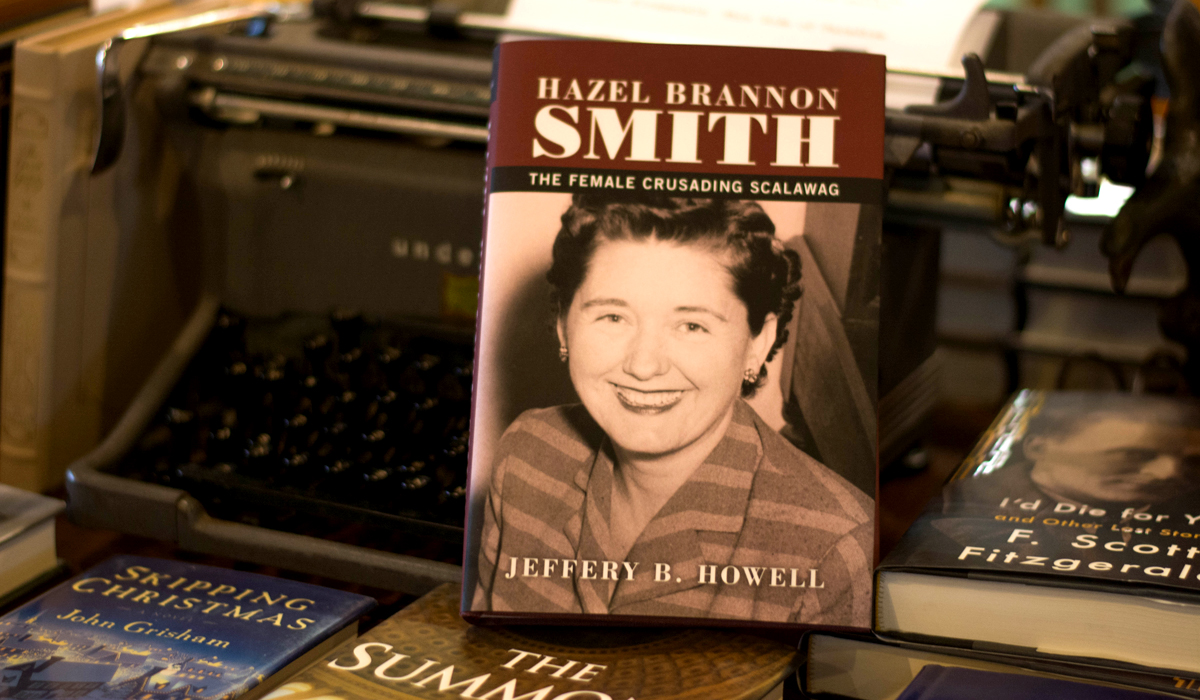

But it’s been nothing like the Carters and other Mississippi journalism dissidents—from Bill Minor with the Capitol Reporter and his later no-prisoners columns, to Medgar Evers and the original Mississippi Free Press crew, to Hazel Brannon Smith (who dared to print the first MFP in the 1960s), to Holly Springs-born Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s defiant investigations of race violence, to J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI spying on the brave staff of the Kudzu—went through.

That knowledge and their courage, which dwarfs anything we face today, have long kept me going and built my strength. If all those brave journalists could challenge the power structure then, we sure as hell can do this now.

We kind of owe it to them, when you think about it.

‘Do It. Challenge It All.’

Hodding III’s impact on me and Free Press journalism here was more direct than distant inspiration and admiration, though. After the 9/11 attacks left Todd and me thinking more about putting down longer-term roots here, we started joking constantly at the bar at Hal & Mal’s about starting a local newspaper that would actually seek and serve a more diverse readership than the corporate daily and other local papers.

I connect with a wide variety of people easily, but it still was a crazy idea then in a state I hadn’t lived in for 18 years and where my network was thin when I arrived—so I indeed went to see Hodding in Miami. There, he and I sat in his big Knight Foundation office and talked about Mississippi, and journalism, and racism, and the people media have long ignored or disparaged—and the need for reporting truth to power here again. And, desperately, to challenge the power players and southern strategists in control of Mississippi bent on keeping the old ways while pretending they were something new.

I didn’t detect regret in Hodding for leaving, but he gave me the sense that he knew there was an abandoned torch still left to be passed.

When he had to take a call, I wandered around Hodding’s office filled with fascinating bits and bobs—I’m a stuff person, too—and ran my finger over a Citizens Council badge of some sort he’d collected. I thought of it as a souvenir skull of a fashion, and smiled. I looked at his pictures of the people he’d rubbed elbows with and interviewed (wow) and the adventures he’d had. I thought about the kind of in-your-face journalism I wanted to do in my home state—the one I had fled the day after graduating from Mississippi State, saying I would never, ever live here again.

Rambling in Hodding’s office was a peak and pivotal moment for my future, I know now.

When Hodding hung up the phone, I got up the courage to tell him that I wanted to start a newspaper in Jackson much as his mom and dad had done in Greenville. I half-expected him to tell me not to, that it’s too hard, not worth the stress and money worries. But no.

“You should do it,” Hodding told me. “Go get the @#$%^&* Clarion-Ledger. Do it right. Challenge it all.”

I exhaled, knowing right then that I was about to embark on one of the toughest adventures of my life. And it was harder and more exhilarating and fulfilling than I could’ve imagined that day sitting in Hodding’s office at the Knight Foundation. I didn’t know it then, but Hodding had just flung open the journalism clubhouse door, long closed to so many women, but especially one from the trailer park like me.

Advice, A Check and A Torch

It was Hodding’s response when I sent him an early editor’s note that laid the foundation for the heart and soul of Free Press journalism in Mississippi—and the passionate Mississippians we’d invite to do it with us. Hodding picked up on my obvious tell in the column: I was leaning heavily on voices of the past like his dad and and Willie Morris, another writing hero I never got to meet. I would get to know Willie intimately through his wife, JoAnne, who soon became one of my best friends and helped launch the JFP (and spent some glorious nights in Jackson drinking with Hodding, me and other fabulous loudmouths deeper into the JFP’s tenure).

But early on, I was clearly paranoid about inserting my Neshoba County, gone-for-18-years self into the hallowed journalism firebrand ground of Mississippi lore. I was a woman who had not yet adopted Hazel Brannon Smith’s “I ain’t a lady. I’m a newspaperwoman” as my personal mantra or fully understood Mississippi native Ida B. Wells’ no-apologies journalism mantle. I was trying to crawl up on shoulders of giants I admired, and I was a bit timid about having license to do that.

Hodding saw that hesitation in the column and told me to let that shit go. (I’m on a plane, and my eyes just filled with tears when I wrote the last sentence.) “Go find new Mississippi voices,” he advised me. “Help and train them to tell Mississippians’ stories. Be bold. Don’t rely on the way it’s been done in the past. Create a new kind of journalism there.”

This is what great mentors do. They give you permission; they see your fears and tell you let them go. They ensure you know you can achieve high standards if you put in the work. They reinforce that you don’t have to ask anyone to allow you to do it.

I’ve never gotten better advice, period, and I think I cried a little then, too. Over time, other wise men and women did the same thing for me: I have a folder of multiple letters each from Gov. William Winter (another reformed gradualist) and my buddy James Meredith, for instance, basically saying the same thing in their own ways. Bill Minor would suddenly call up to cheer me on and give me tips (and the occasional correction), and Reena Evers-Everette told me similar things as I was planning the Mississippi Free Press in 2019 and asked her to join the advisory board. Keep going. Continue challenging. Lift all the voices. Speak the truth, no matter what. Don’t stop. Be brave.

But it was Hodding who first opened the permission gate for me. And I’ve never once looked back or regretted challenging the status quo from elected officials to power-hugging media in Mississippi. The truth today grows from seeds that fearless giants planted in decades past—but as Hodding counseled me 20 years ago, it takes fresh voices and thinkers to teach it to newer generations.

Hodding’s golden advice to me was the moment I realized what “passing the torch” really means—or, hell, helping light it for passionate people around you. When I asked Kimberly Griffin in 2019 to help me fulfill a 20-year dream and co-found the statewide Mississippi Free Press, I had the torch on my mind. That is, I launched the MFP with my succession (hopefully into book-writing, finally) as a top goal.

I want to, in my way, help an amazing team of Mississippians take the Free Press baton and grow it into the journalism future generations in our state need long past my tenure. Like Hodding did with me.

He also sent me a check. Just one day, randomly in the JFP’s early scrappy days, it showed up in the mail. It wasn’t humongous, but it was significant for us then and probably catapulted us past disaster. He wasn’t trying to be an investor or buy stock, nor did he want a receipt. He just sent a surprise check. It was another way to say, “Keep going. You’ve got this.” God bless him.

Gesturing and Hootin’ and Hollerin’

Not all my memories of Hodding, though, had to do with mentoring, bullies and bravery. A lot of it was about belly laughs, even related to very serious history and the absurdity of what Mississippians worship.

I remember discovering that Robert “Tut” Patterson, the Delta plantation owner and original founder of the Citizens Council, had been inducted into my alma mater Mississippi’s State’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1995 because he’d been a football star there back in the 1940s. Of course, the hateful Council part wasn’t mentioned in the write-up I stumbled into on State’s site, but Patterson’s obituary later in 2017 bragged about how he organized it “to defend State’s Rights,” as well as his co-founding the then-whites-only Pillow Academy.

I sent the Hall of Fame write-up to Hodding with, as I recall, a few choice cuss words for old man Patterson being honored in such a way. Hodding emailed back guffawing in disgust at the funny-not-funny story of his family’s old nemesis getting such a nod from State. (Not the University of Mississippi, mind you, which takes nearly all the collegiate hits for holding on tight to the old racist ways, providing unfair cover for what leaders of universities like mine did.)

I wish I could still send Patterson’s 2017 obit, which I discovered recently, to Hodding with more sassy annotations. It’s certainly not funny for Tut’s family to brag about his terroristic activities, including against the Carters, decades later, but it sure proves the work journalists still have to do, and do well, as well as the enduring devotion to racist systems still having the old desired effects in many ways. As I knew when I started the Jackson Free Press in 2002, honest “race coverage” meant much more than putting old Klansmen in prison—I was for that, too—but finally facing generations of race-driven inequities that the white-supremacy conspiracy mob on all levels of Mississippi white society together created and enforced.

That is, many bright torches are needed to continue the work of dismantling racist systems.

Over the years, there was nothing quite like Hodding coming to town and ending up out drinking while trying to keep up with his brilliant prattle. When Schimmel’s was still open in Fondren, its bar was the place if you liked to get pulled into uproarious insult battles and constantly interrupt each other with a quip or a crazy story. I loved walking in there and getting sucked into happy-hour chatter with the likes of business genius Dr. Bill Cooley (another great supporter of younger people who shares responsibility for ensuring the Free Press grew and built a deep and wide readership) and Bill Dilday (once the only Black TV general manager in the U.S. after WLBT was successfully challenged over racism).

Hodding, JoAnne, my partner Todd and I were getting together, so I suggested the Schimmel’s bar. I had an idea that Hodding would dig it. Long story short, Hodding ended up in the middle of a semicircle booth gesturing and hootin’ and hollerin’ and trying to one-up the regulars there with the rest of us doing our best to just stay in the damn game. I seem to remember a roaring hangover the next day, but that is one of the best nights I’ve ever had in Jackson, or anywhere.

Another was at Hodding’s daughter Catherine’s house here with Hodding’s wife, Patt, JoAnne and power couple Judge Edward Ellington and his fabulous artist wife, Cleta Ellington. They have deep ties in Lexington, Miss., where editor Hazel Brannon Smith took on the Citizens Council and KKK, and now native attorney Jill Collen Jefferson is challenging the racist legacy of those terrorists now.

Amid ebullient storytelling and historic gossip, I mostly stayed quiet, listening and soaking up the stories, including about media and political figures and, of course, those bigot business suits of the day. It was a delight to be with and learn from an amazing roomful of people who paved many roads for us now. I was like the proverbial kid on the stairwell listening to the elders share mirth, wisdom, hope and inspiration—and damn good stories and tattle about those no longer with us.

‘Not Gods or Superheroes—Mere Men and Women’

Over two decades of knowing him, I spent little time in Hodding Carter III’s physical presence, but his wit and wisdom had an outsized effect on my life and work and, by extension, those around me. I thank him, especially, for taking me seriously and not patting me on the head and saying, “that’s hard, you know,” like way too many powerful men like to do to ambitious women if they bother to acknowledge us at all. Some, of course, just pretend not to know who we are to keep us in our place.

I leave you with Hodding III’s closing words from his Nieman fellowship essay from decades ago, which I hadn’t seen before starting this tribute to him.

“It’s an old lesson, but too often unlearned or forgotten,” he wrote. “Mortal men and women set course, encounter adversity, are terrified—and press on. Not gods or superheroes—mere men and women. The enemy can be as determined and vicious and lethal as the white racists of Mississippi a half-century and less ago—or even worse or even less. What is required, what Dad showed me, is that you suck up your gut and do the best you can.”

Rest in peace, friend and teacher. We’ll keep the torch burning for you, I promise.