A’sheena Woods had been sitting in her friend Lorrie’s home in Picayune, Miss., when a police car coasted into the driveway, lights flashing. The 15-year-old peered out a window and saw two officers exiting a vehicle and stepping toward the front door. She turned to face Lorrie, who had already begun scrambling through a nearby open window.

The two officers noticed Lorrie and gave chase on foot around the house. Woods calmly opened and walked through the front door, attempting to avoid drawing attention to herself. One of the officers, however, spotted and stopped her at the end of the driveway.

Woods recalls that she could not answer truthfully to the barrage of questions that followed out of a fear that the authorities would return her to the Department of Human Services’ custody. She did not want to live in a shelter or group home awaiting yet another foster family.

An officer placed her into the backseat of his cruiser before taking her to the Picayune police station, checking her in and guiding her to a room in the back. He explained that Woods would need a parent or guardian to pick her up so that the police department could release her.

Her mind ran in circles. The teenager did not have a parent or active guardian, and the last thing she wanted to do was call DHS.

A woman Woods had never seen before entered the room with another officer.

“A’sheena, where are your clothes?” the woman, whose name was Carolyn, asked. She gestured towards Woods’ shorts. “You know your parents would tear your butt up if they caught you wearing those.”

Initially confused, Woods soon understood Carolyn’s motives and played along. After a short conversation between Carolyn and the police, Carolyn signed some paperwork and took Woods to her home.

“She came in like she was my auntie, and the police released me to her.” Woods told the Mississippi Free Press. “She provided me with a room in her house, and she was just so sweet to me.”

This moment was pivotal for Woods and her story as someone who had lived inside Mississippi’s foster-care system. Carolyn provided Woods with the love and stability the teenager found absent in the home of her biological relatives whom DHS had assigned as her foster family, she said.

“When I was on the run, I got beat up really, really badly,” Woods disclosed. “So I tried coming back, but I ran away again because I wanted freedom, and I was tired of being in shelters and all these different facilities being diagnosed with anxiety and depression when, really, all I wanted was to be loved.”

The relationship between Carolyn and Woods—defined by how Carolyn supported Woods despite lacking any biological connection—is very similar to the concept of fictive-kin placement, where Child Protection Services places a foster child in the custody of a non-family member the child trusts. Techie Fenton, a foster-parent recruiter who has worked for the Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services since 2005, emphasized the department’s willingness to use fictive-kin placement.

“The Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services is now a family-centered practice agency, meaning that we work to keep children within families and their communities more than placing them within non-relative settings or unfamiliar communities,” Fenton said. “So, saying that, it might not be a blood relative, but it could be a neighbor that child is close with.”

The goal of both relative and fictive-kin placement is to keep foster children within a community of some sort. With relative placement, the family unit is considered community enough. Fictive-kin placement stresses the importance of geographic, physical community, allowing children who do not have many direct relatives they feel comfortable around to otherwise have homes that provide more direct care.

“Right now, there is a critical need for foster homes,” Fenton said. “In my region, we have 336 children in custody, which means we are lacking 336 homes.” This number, while perhaps jarring, is just under 9% of the statewide total of 3,776 foster children without homes.

Fenton’s goal—and that of the Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services at large—is to find homes for these young Mississippians, she said. To meet this goal, MDCPS has simplified the application process for foster parenting.

“MDCPS is open to working with anyone who can pass a background check, is at least 21 years of age, has no more than four children in their home and is financially self-sufficient,” Fenton explained. “After application, the process for placement with a relative is 90 days while placement with a nonrelative can take up to 120 days.”

Baby Boxes and Updated Safe-Haven Laws

While the process of getting a foster child to a loving, supportive family is often a long one, Britney Diaz-Roman, a Pearl River Community College student who recently established the Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship for Fostering Educational Opportunities, suggests that Safe Haven Baby Boxes can be an effective solution for shortening the adoption process.

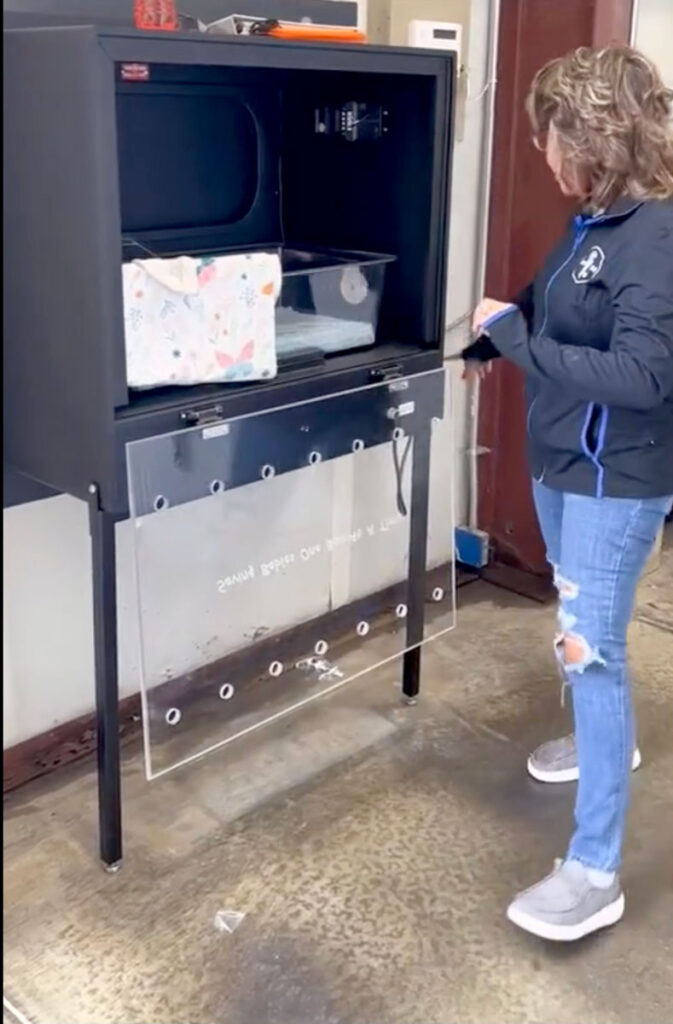

Safe Haven Baby Boxes are medical-grade bassinets that technicians install onto the exterior of a fire department or hospital in which someone could anonymously surrender a child. Once the child is inside the box, the exterior door locks, and first responders are alerted. Medical professionals then access the surrendered child through the interior door of the baby box and begin the process of placing the child within foster care. Diaz-Roman claims that the next step in her efforts to support Hattiesburg’s foster-care community is to bring Safe Haven Baby Boxes to Mississippi.

“This is one of those things we can do to put children from birth into adoption, rather than them being born, the mother not knowing what to do, and the child ending up in foster care for a while,” she said. “With Safe Haven Baby Boxes, the mother can directly put the child into the safety of the box and the child can go into adoption.”

Safe Haven Baby Boxes operate under Mississippi’s Safe Haven Law, a set of codes allowing for parents to surrender a child to medical professionals. In 1972, the Mississippi Legislature implemented the Safe Haven Law allowing medical-service professionals to “take possession of a child who is seven (7) days old or younger if the child is voluntarily delivered to the provider by the child’s parent and the parent did not express an intent to return for the child” (Miss. Code § 43-15-201).

This legislation also ensures that the parent who surrenders the child remains anonymous and prevents hospitals from listing the parent’s information on the surrendered child’s birth certificate, allowing the parent to legally forfeit their parental rights and separate themself from the surrendered child.

Where Mississippi’s Safe Haven Laws have fallen short is with the short seven-day window in which a parent can legally surrender their child. Any newborn older than seven days is not eligible for surrender under this definition and unviable parents would be legally tethered to their child if they did not surrender within this window.

Seven days may not be enough time for parents to make decisions about surrendering their children. “Sometimes mothers can still be in the hospital after seven days,” she said. “There is a lot of pressure on a mother to make such a big decision so shortly after giving birth.”

Restrictions such as this, as well the fear of social stigma that comes with non-anonymous surrender, has led to the improper abandonment and deaths of two Mississippi infants in the past year. One of the infants had been abandoned on a porch in Southaven in March 2022.

The Mississippi Legislature recently amended Mississippi’s Safe Haven Laws through House Bill 1318, which Gov. Tate Reeves signed into law in April. This law extends the maximum window for which a parent can surrender a child from seven to 45 days after birth. The law also further protects the anonymity of parents, allowing them to surrender children by proxy and preventing hospitals from disclosing any personal information to “any state or local agency or any other person.” Also within the new law are definitions that allow Mississippi cities to utilize Safe Haven Baby Boxes without having to pass additional ordinances.

This law’s emphasis on furthering anonymity is drastically different from language proposed in Senate Bill 2377, which died in committee in February 2023. That bill would have required MDCPS to “conduct a reasonable search for the relatives of the child.” This search would require the surrendering parent to provide authorities with the other parent’s personal information, further decreasing the protections around parental anonymity.

“The whole point of the Safe Haven Baby Box is that it is an anonymous option for parents in need,” Diaz-Roman clarified, stressing the need for language protecting anonymity in H.B. 1318. “Not attaching a parent’s name is respectful to both the child and family in this situation.”

Diaz-Roman argues that bringing Safe Haven Baby Boxes to Mississippi may be more important now than ever in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 overruling of Roe v. Wade in the Mississippi case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

“With Mississippi’s decisions on abortion access, it is increasingly important for our state to have resources like the Safe Haven Baby Box available for women,” Diaz-Roman said. “Hopefully through these baby boxes, we can see more options for women who might not be able to handle children.”

In post-Dobbs Mississippi, parents lack options for the safe and anonymous surrender of their parental rights. Though the bill does not address the lack of options in Mississippi for parents before birth, the new law could begin to alleviate some of the difficulties that hinder both parents and children in the twilight of abortion rights.

Recent Scholarships for Foster Children

Britney Diaz-Roman’s efforts to bring Safe Haven Baby Boxes to Mississippi is a continuation of the philanthropy she started for her entry into the Miss Pearl River County Pageant, a title she won in November 2022. Originally, she was interested in improving literacy rates on campus, but the 21-year-old shifted her focus to students who had lived in the foster-care system after learning about their under-representation in higher education.

“I learned that with foster youths, less than 6% attain a four-year degree, and less than 4% attain a two-year degree,” Diaz-Roman said. “So, I wanted to help ensure these foster youths have the same education opportunities that non-foster youths have.”

To do so, Diaz-Roman organized a 5K to establish the Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship for Fostering Educational Opportunities, which will provide financial assistance to foster-care students pursuing higher education at Pearl River Community College. The scholarship’s namesake is the former vice president of the Forrest County Campus, who retired from his 43-year career at PRCC in 2015.

Diaz-Roman’s scholarship is one of many resources offered to foster children and teenagers to combat this inequality within higher education. Notably, students who were in the foster-care system after age 13 are automatically awarded the maximum Pell Grant amount when applying for federal student aid, regardless of their family’s income. This grant alone would award a qualified young person $6,895 for the 2022-2023 award year and $7,395 for the 2023-2024 award year, money that directly funds education and does not need to be repaid.

Even though this grant is helpful for young people in foster care pursuing higher education, Fenton admitted that the Pell Grant is not perfect and does not address all the financial difficulties that foster students face as they transition out of the foster-care system.

“Pell Grant doesn’t pay for all their education, so they are still left with debt after graduation,” Fenton said. “Pell grant(s) might cover tuition at a school like (Jones College, a community college), but not at a major university. They’re going to have debt left over.”

This assertion proves true for schools such as the University of Mississippi, where the total cost for in-state students living on campus was $26,946 per year for the 2021-2022 term. While the Pell Grant would cover a considerable portion of this cost, students would still be left with more than $20,000 of educational fees to finance through loans, alternative grants, scholarships or other sources. These costs would likely increase dramatically for students pursuing out-of-state education, with the University of Mississippi’s out-of-state cost increasing to $43,788. Other major universities in Mississippi and beyond have comparable expenses.

Diaz-Roman also suggests that the Pell Grant excludes some students who have been in the foster-care system prior to becoming teenagers, something she hopes her scholarship can remedy at PRCC.

“The Pell Grant only applies to students who are in the foster-care system after age 13, so if a child is adopted earlier than that, they would not necessarily receive the full grant,” Diaz-Roman explained. “One of the reasons this scholarship is important is that foster youths who are adopted before age 13 are eligible for it as well.”

At PRCC, the full Pell Grant could cover the entirety of a student’s tuition fees this award year, with in-state students staying on campus paying only $5,280 per term, but foster students who were adopted before turning 13 could be left with more debt after graduation, as they may not receive these funds.

Young people in foster care who are adopted after age 13 are automatically considered independent on the Federal Application for Student Aid, unlike those adopted while they are 12 years old or younger. Although children who are adopted before they become teenagers could potentially file for FAFSA as an independent and receive the full Pell Grant amount, these funds are not guaranteed for them as they are for foster youths who are adopted later in their lives.

But Britney Diaz-Roman is not the only advocate for making education financially more accessible for foster students. A’sheena Woods, who is now the owner and founder of the Hattiesburg Art Barber College, is in the process of founding a scholarship for former foster children who want to attend her school. The scholarship would cover full tuition for Woods’ program, which totals to approximately $8,000.

Much like the Dr. Cecil Burt scholarship, Wood’s scholarship will not exclude foster students who were adopted before age 13, separating these scholarships from the stricter age restrictions of the Pell Grant. However, the Art Barber College Scholarship will have other stipulations associated with it, such as the applicant needing a recommendation letter and reliable access to transportation. Applications for the 2023-2024 academic year are open through June 26, 2023.

PRCC has yet to announce further stipulations regarding the Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship application process, if any.

Much of Woods’s reason for offering this scholarship is due to the difficulties in education that she faced as a foster student. After her emancipation at age 18, Woods was effectively left to fend for herself.

“When I was relieved from custody, there were never any resources for school or anything like that,” she said. “I do think that there were resources available, but because of my situation, I didn’t have access to any of those resources.”

She enrolled in a private school, which did not receive government funding, to continue her education. “I was considered independent, but since it was a private institution, I never had any federal funds for education,” Woods said. “I always had to have a job.”

Eventually overcoming the setbacks in her education, Woods earned her high-school diploma from Penn Foster Online after turning 18. From there, she began her journey into higher education, studying at Blue Cliff for cosmetology, though she did not complete her degree. She later attended Brookhaven Barber College and earned her barber-stylist license. Using this license and experience, she founded the Art Barber College in Hattiesburg in 2020, where she now teaches and certifies aspiring hair stylists.

Woods was one of many foster children who did not have access to some of the resources that both the Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services and the federal government offer. The Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship differs from other resources in how it lacks any stipulation for eligibility other than the student having been in the foster-care system at any point in time.

Tiechie Fenton argues that a significant part of scholarships such as the ones that Woods provides and Diaz-Roman created is that they are solely dedicated to students from the foster-care system.

“I think it’s very important for foster children because it’s developed only for foster children,” Fenton said, referring to the Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship. “Some of our children will not be adopted and go on to live independent lives. With that extra funding, there is more money dedicated to supporting their education, and I think that is a blessing to the foster-care system.”

For more information on foster parenting or to apply to become a foster parent, visit the Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services website at mdcps.ms.gov or call 1-800-821-9157. Alternatively, potential foster parents in Marion, Forrest, Perry, Stone and Lamar counties can contact Tiechie Fenton directly at 601-383-6811.

To contribute to the Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship for Fostering Educational Opportunities online, visit prcc.edu/alumni/donate, select “general scholarships” from the drop-down menu and write “Dr. Cecil Burt Scholarship for fostering Educational Opportunities” in the comment box. Checks can be made out to PRCC Development Foundation and mailed to PO Box 5389 in Poplarville, Miss., zip code 39470, with the name of the scholarship noted on the check.

To apply for the Art Barber College Scholarship, email A’sheena Woods at artbcollege@gmail.com. Applicants must have previously been or currently be in the foster-care system, be 18 years of age or older, provide a recommendation letter and have reliable access to transportation. For more information about the scholarship or The Art Barber College (102 W. Florence St., Hattiesburg) itself, call 601-270-6588 or visit the school’s Facebook page.