Willie Cory Godbolt entered his in-laws’ house in Bogue Chitto, a small community near Brookhaven, Miss., on Saturday, May 27, 2017, where he began to argue with his estranged wife, Sheena May Goldbolt, over custody of their son and daughter. Sheena had moved out of their shared mobile home following a pattern of violence from Cory, 34 at the time. When the disagreement escalated, Cory pulled out a pistol and opened fire.

Sheena fled the room alongside her two children, and the three escaped out of a window. Godbolt, however, fatally wounded his mother-in-law, Barbara Mitchell, 55; his sister-in-law, Toccarra May, 35; and Sheena’s aunt, Brenda May, 53. Sheena’s stepfather, Vincent Mitchell, escaped harm.

After receiving notification of a domestic disturbance, Lincoln County Sheriff’s Deputy William Durr drove to the Mitchell home, where Godbolt subsequently shot and killed the law-enforcement officer.

Early the next morning, Godbolt walked to a nearby house on Cooperton Road and fired rounds into the door’s lock until he successfully kicked in the door. Once inside, he shot 18-year-old Jordan Blackwell and 11-year-old Austin Edwards. Either shrapnel or a bullet grazed the head of Edwards’ brother Caleb, 11, who survived the invasion.

A few hours later, the since-convicted spree killer broke into the Lincoln Road home of married couple, Ferral and Sheila Burage, 45 and 46, respectively. He killed them both and continued down the road until law enforcement from multiple jurisdictions arrived to apprehend Godbolt. The murderer later admitted he planned to commit suicide-by-cop, but he instead took a bullet to his right arm, which allowed officers to arrest him and send him to a hospital for treatment.

‘You Know I’m Never Going To Leave You Alone’

While Godbolt’s attempt at suicide failed, his case demonstrates a systemic link between domestic violence and potential murder-suicides.

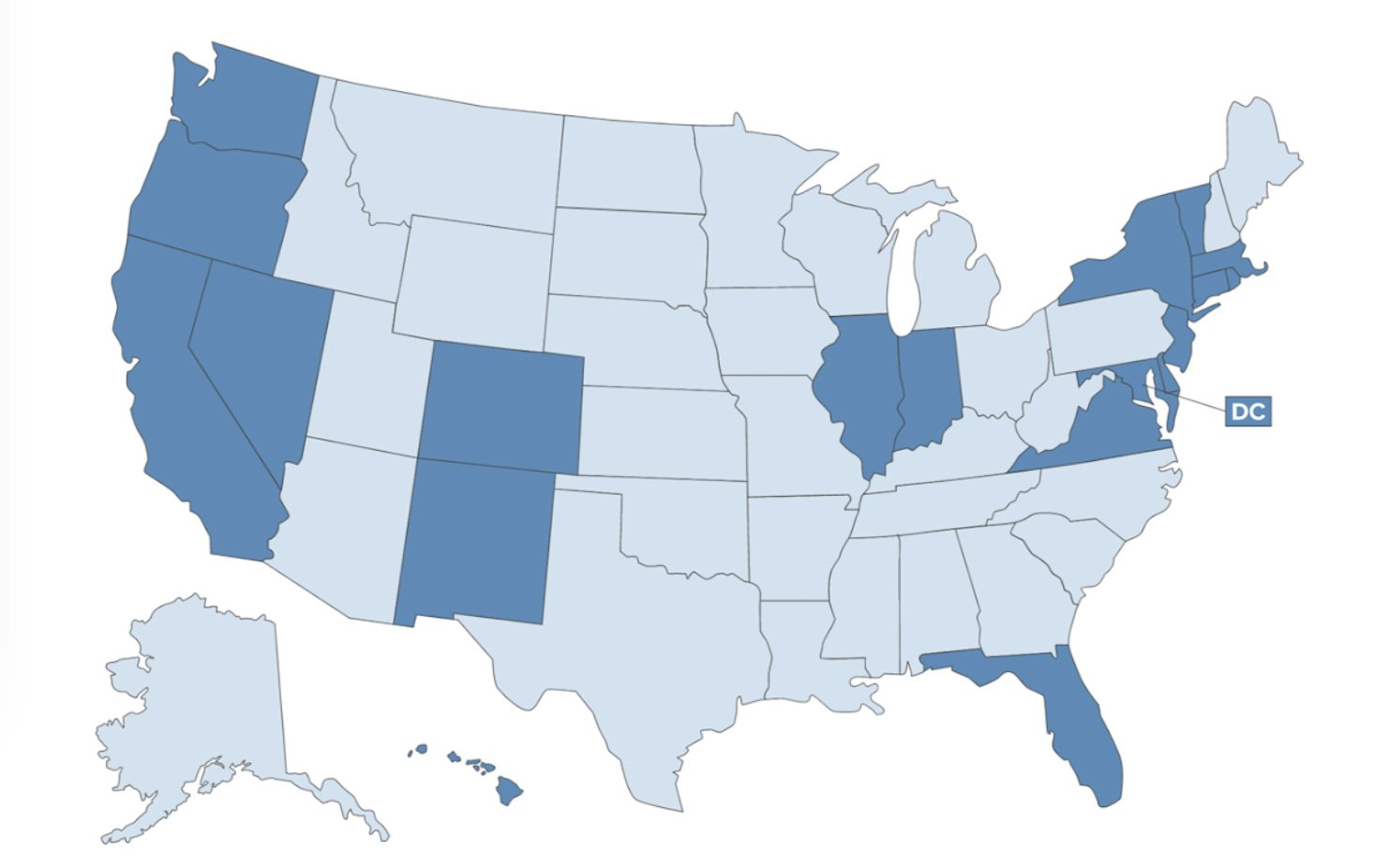

Studies put the number of murder-suicides as high as 1,500 a year, most of them consisting of men killing their intimate partners. The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting assembled a database showing that more than one in seven murder-suicides in 2019 and 2020 involved the killings of children. More than nine out of 10 children who died as a result of murder-suicides were victims of “filicide,” which is when a parent kills their own child. Most of these incidents took place in the South, with some outliers. Texas, California, Oklahoma and Florida take the top spots.

In the picturesque California neighborhood of Paradise Hills, Jose Valdivia entered his estranged wife Sabrina Rosario’s home, a single-story, light beige house with a dark wooden roof, in 2019. Inside, Valdivia murdered his and Rosario’s children—Zeth, 11, Ezekiel, 9, Zuriel, 5, and Enzi, 3—along with Rosario before turning his weapon on himself and committing suicide.

This suburban nightmare was just one of multiple cases of murder-suicide that made headlines in the last few years. But parents killing their children is more common than most people think. Every year, about 500 arrests are made in cases where these “filicides” occur.

The youngest child killed in 2020 was only 5 months old.

After filing for divorce in June 2019, Rosario was overwhelmed with a stream of abuse from Valdivia. The harassment quickly escalated. On Nov. 6, Valdivia sent her a picture of a handgun—placed in front of several empty beer cans and a bottle of alcohol, court records show.

He texted her repeatedly, sometimes sending messages minutes or even seconds apart. On Nov. 8, just a week before the attack, Valdivia called her 11 times between 7:34 a.m. and 7:40 a.m. That same night, he texted her he was coming over. Fifteen minutes later, even with no response, he showed up at her house unannounced.

She had told Valdivia she would file a restraining order against him if he continued this behavior. But he brushed her off. “A restraining order is not going to do nothing,” he said. This barrage of unwanted contact continued until the very end.

On Nov. 14, 2019, two days before the attack, Valdivia sent Rosario a message: “You know I’m never going to leave you alone.” She filed for a restraining order the next day.

Rosario felt threatened. She was worried for her children’s safety. “I am requesting that our children be protected in this order … it is not in the children’s best interest to be around this kind of domestic violence,” she wrote on her child-visitation and custody filing, court records show.

Valdivia killed Rosario and her four children the day after she filed for the restraining order.

‘In the Context of Domestic Violence’

Some perpetrators kill their children to retaliate against a current or ex-partner, a 2007 review of filicides in the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law explained. Fathers killing their children or “paternal filicide” has its own category. The review found that fathers who commit filicide are more likely to kill very young children and children later in their lives. Fathers were also almost twice as likely to take their own lives after killing a child than mothers were.

“I think of murder-suicides specifically in the context of domestic violence,” Ruth Zakarin, executive director of the Massachusetts Coalition to Prevent Gun Violence, said. “I cannot recall an instance where a murder-suicide didn’t involve intimate partners, current or former, or family or household members.”

Of the paternal filicide cases analyzed in the MCIR 2019 and 2020 murder-suicide database, all of the killers had histories of domestic violence and restraining orders or protection orders against them. During the pandemic, this number doubled from 14% to about 28%.

On the other end of the spectrum, some perpetrators have major psychiatric illnesses. These are called pathological filicides, according to the same study. Cory Godbolt, for example, while speaking in court, blamed the devil for his actions on the night he killed eight people in the South Mississippi towns of Brookhaven and Bogue Chitto.

‘Something Could Have Been Done to Stop Tragedy from Occurring’

Murder-suicides—or attempted ones in the case of Cory Godbolt’s 2017 rampage in Brookhaven—may share characteristics with mass shootings like that in Uvalde, Texas, that left 19 elementary school students and two teachers dead, says Adam Lankford, a professor of criminology at the University of Alabama. In both instances of murder, four or more people may sometimes be killed. Guns are also usually the weapon of choice for both.

“Mass shootings are often premeditated crimes in which there were multiple warning signs observed by friends, family members, teachers, or other witnesses,” Lankford said. “This means in many cases, something could have been done to stop tragedy from occurring.”

Alcohol abuse and mental illnesses are distinct risk factors for murder-suicides, a 2009 study reports. Domestic violence is another factor that increases risk of murder-suicides, the same study found. The pandemic heightened some of these statistics, as many people had to shelter in place—sometimes in households with domestic violence. MCIR’s investigation found that, in 2020, more than four of five murder-suicides happened in the home, and 96 perpetrators had a history of domestic violence.

These issues in combination with recent separations or impending divorces are often major contributing factors in murder-suicides, including filicides. A 2009 study into filicides in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law found that “depression often follows a breakup and then triggers the murder-suicide event.”

But in many cases these warning signs are missed, especially within law enforcement and the legal system. As of today, no national database tracks murder-suicides, so there is no way of really knowing how many children died as a result of filicide. Some states did not report any data, and some provided incomplete data or left out whole years when reporting to the FBI.

This oversight may be because reporting children killed in homicides is voluntary. In California’s Butte County, for example, a 2014 study in the National Library of Medicine found that detectives and the court did not track the number of restraining orders or respondents.

Perpetrators use guns to carry out a majority of murder-suicides in instances that involve histories of domestic violence, MCIR’s investigation found. Some states require those served with restraining orders to relinquish their firearms. Mississippi is not one of those states.

Even when those under restraining orders are required to relinquish their firearms, the responsibility of surrendering firearms falls on the person against whom a restraining order is placed. A 2010 study in Los Angeles and New York found only 12% of abusers who possessed guns had relinquished those guns or had them removed. While law enforcement successfully removes firearms from a number of high-risk individuals, respondents of restraining orders often deny possessing firearms. In many states, like California, they cannot be compelled to give up their firearms and face no punishment for refusal.

“Laws that explicitly place responsibility on law enforcement to facilitate or realize gun dispossession when people are prohibited can help address (this) shortcoming,” Shannon Frattaroli, director of The Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy at Bloomberg School of Public Health, said.

“Initiatives within law enforcement agencies that emphasize law enforcement’s role in assuring dispossession—for example, by setting up tracking databases to monitor when guns are removed and alert supervisors when they are not—can help incentivize efforts to follow through when orders are issued that prohibit gun possession for a period of time.”

Ruth Zakarin, who has provided training on domestic violence, sexual assault and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as on approaching survivors of interpersonal violence, said her experiences with law enforcement were challenging.

“I experienced a lot of resistance from participants, including being openly challenged on the content or my expertise,” she said. “I found that training felt more impactful with the ranking officer in the room setting the example of saying the training was important and managing the resistance or challenging behaviors as they came up. Basically, if the senior person in the room demonstrated buy-in, the training went better. If not, it was much harder.”

Law enforcement rarely, if ever, measures the effectiveness of these kinds of training, Zakarin said, leaving her observations unverified. “I can only speak to my own experiences with that, which were very challenging,” she explained. “I don’t have a sense of either effectiveness overall, or attempts to measure that.”

Closing ‘Loopholes’ and Mitigating Chances for Violence

Some states like Massachusetts are adopting “common sense” legislation. Zoe Grover, executive director of Stop Handgun Violence, says this is the best way to close loopholes in the already existing laws that make it possible for individuals, even with a domestic violence misdemeanor, to purchase firearms.

Federal law prohibits people convicted of domestic violence from purchasing a gun, but only if they are living with their partner, married to their partner or have a child with their partner.

While federal law bars domestic abusers from having guns, a “boyfriend loophole” remains for men who have not lived with their partners or had children with the partner.

“Even if there is a substantial dating relationship between two individuals, violence between them may not qualify as domestic violence under some state laws if they do not live together or have never been married,” Grover said. “Closing loopholes around the definition of domestic violence and requiring that all firearm purchases require a background check would be a common-sense start.”

U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., helped push a bipartisan effort to close that loophole and make other reforms, saying this progress “breaks a 30-year log jam, demonstrating that Democrats and Republicans can work together in a way that truly saves lives.”

The bipartisan U.S. Senate gun-safety bill, which passed the Senate on June 23, 2022, and the House on June 24, expands the definition. Individuals in a “current or recent former dating relationship” who are convicted of domestic abuse would also be prevented from purchasing a gun.

In 2019, the Justice Department launched a program designed to help communities prevent abusers from having access to guns in domestic-violence cases. Then-U.S. Attorney Michael Hurst of Jackson persuaded the Justice Department to invest $6 million to help reduce domestic violence in Mississippi.

When abusers threaten to use weapons, women are 20 times more likely to be killed than other abused women. The Department of Justice has now expanded its program to crack down on these abusers.

Like many other states, extreme risk protection orders, or ERPOs, are another measure that are underused to combat gun violence and domestic violence in Massachusetts, Grover said. Also called “red flag laws,” these protection orders allow law enforcement and family members to petition the courts to temporarily seize or prevent the purchase of firearms for up to 12 months. Of the top 10 states leading in the nation’s murder-suicides, three of them have these laws: Florida, California and Virginia. Nationally, only 40% of states have extreme risk-protection order laws. Mississippi does not.

In some states, these laws have already proven effective. In 2018, in Maryland, a red-flag law received legislative approval. In the five months between the passage of the law and its implementation, law enforcement trained to introduce families to the red-flag law. Courts in Maryland can now process petitions 24 hours a day, allowing firearms to be seized quickly in critical situations.

“We still believe they are an important part of the tool box,” Grover said. “Restraining orders, child-protection orders, domestic-violence restraining orders and extreme-risk protection orders work together to make sure that individuals who are in crisis do not fall through the cracks.”

MCIR Executive Editor Jerry Mitchell contributed to this report.

The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting—a nonprofit news organization that seeks to inform, educate and empower Mississippians in their communities through the use of investigative journalism—produced this story, which the Mississippi Free Press edited for republication. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletter here.