White cotton still covered the fields at Parchman Farm in December 1918, dashing hopes for a record-setting year for profits. The 1918 influenza pandemic had swept through Mississippi’s prisons that fall, and imprisoned laborers at the penal farm in Sunflower County, whose founder had modeled the Mississippi Delta prison after slavery plantations, were too ill to work.

While other Mississippians were able to quarantine themselves to avoid the deadly virus, the prisoners in their close quarters had no such luxury. The pandemic ultimately killed about 675,000 Americans.

History could repeat itself. Today, the conditions in Mississippi’s prisons still make them fertile ground for an outbreak that quickly becomes hard to contain, much as in 1918.

“This is a perfect storm, and I’m afraid it only exacerbates pre-existing problems,” J. Robertson, the director of employability and criminal-justice reform at Empower Mississippi, told the Mississippi Free Press Wednesday afternoon.

Empower Mississippi is a libertarian-leaning lobbying group that works on criminal-justice reform issues with FWD.us, a bipartisan criminal-justice reform organization funded by business and tech-industry leaders. On Tuesday, the Silicon Valley-backed group released a report highlighting the threat Mississippi inmates face.

“The conditions in Mississippi’s prisons are ripe for the rapid spread of COVID-19, because the system is operating at close to its maximum capacity, and many incarcerated people live in close-quarters dorm style housing,” the FWD.us report warns. “On top of these dangerous conditions, many incarcerated people are particularly vulnerable to the virus. There are more than 1,000 people in prison aged 60 years or older, and more than 500 people in Mississippi prisons have been deemed medically high-risk.”

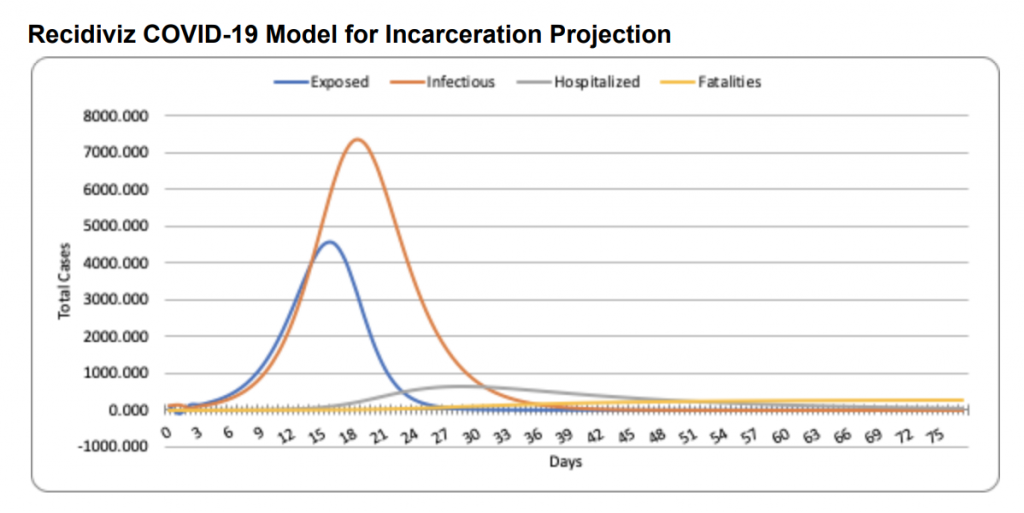

Report Predicts 18,000 Infections

Unless Mississippi takes major steps to reduce the populations in its prisons, the virus will infect “nearly every individual in Mississippi’s prison systems in about a month,” the report says.

In a statement Tuesday, FWD.us Mississippi State Director Alesha Judkins urged Gov. Tate Reeves to take action.

“Gov. Reeves must take bold steps to reduce the number of people in prison immediately and ensure the health and well-being of nearly 20,000 people incarcerated in Mississippi’s prisons, facility employees and the surrounding communities,” Judkins said.

On April 16, the Mississippi Department of Corrections announced its first COVID-19 death, an inmate at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman in Sunflower County. At that point, the State had only tested 20 inmates at all prisons across the state, but four inmates and four guards had already tested positive. Robertson said he would like to see more transparency from the Mississippi State Department of Health when it comes to the number of cases that authorities have identified in each prison across the state.

FWD.us estimates that the novel coronavirus will reach its peak in Mississippi’s prisons within a month unless Reeves takes action soon.

“In three weeks, more than 18,000 incarcerated people—nearly every individual in MDOC custody—will have the virus. At the hospitalization peak in one month, at least 600 incarcerated people will be hospitalized, utilizing 5.6% of Mississippi’s total hospital bed capacity,” the FWD.us statement predicts.

The group’s model predicts that 186 incarcerated Mississippians will die in prison from the virus if the governor takes no steps to mitigate the situation. On the day the report came out, slightly fewer Mississippians than that have died statewide; the Magnolia State death toll reached 183 on Tuesday morning. It had climbed to 193 Monday afternoon, as the total number of known cases neared 5,000. Today, April 22, MSDH reported 178 new confirmed cases and 10 more deaths.

“The governor is the only one that could act right now because the Legislature is gone,” said Robertson, the Empower director.

The Legislature went on hiatus in March as COVID-19 began to spread across the state.

“The governor can commute and have people released immediately at his discretion,” Robertson said. “The authority there is pretty broad. I think the question is how can they do that in a way that supports the goals that everybody has right now to protect public health and stop the spread of the virus, but also to ensure they’re protecting the public safety.”

Groups Call for Reeves to Release 5,000

FWD.us says Reeves could reduce the projected deaths by about 24% “and save thousands from the deadly illness” if he released 5,000 individuals, prioritizing the most “vulnerable” and those “whose punishments most dramatically exceed the nature of the offense,” such as non-violent offenders serving “extreme” sentences.

If Reeves took action to cut the prison population by about a quarter, the report says, he “would be following the lead of conservative leaders from Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas and the federal government who have taken steps to reduce incarceration during this pandemic.”

On Tuesday, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced that 38% of coronavirus infections in his state are concentrated in Cummins Prison, a maximum-security facility in Gould, Ark. State officials there confirmed 260 new cases at the prison Tuesday, bringing the total infected number of inmates at Cummins to 850. The prison only holds about 1,200 inmates.

Ohio’s Marion Correctional Institution has reported a similarly widespread outbreak, with that state confirming that 73% of inmates there had tested positive for COVID-19 by April 19.

On April 19, Hutchinson, a Republican, said he had directed the Arkansas Parole Board and the Board of Corrections to review a list of 1,990 non-violent, non-sexual offenders statewide who are due for release within the next six months. The State will determine who gets released early “from a public-safety standpoint,” he said.

Similarly, in early April, the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles began reviewing some inmates for early release as well, with an aim toward releasing up to 200 inmates over a 30-day period. On April 2, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey issued an executive order allowing county jails to reduce their inmate populations so long as they did so “in a way that does not jeopardize public safety.” Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear commuted nearly 1,000 sentences by early April.

Mississippi’s governor has not yet indicated that he plans to take action to curb the prison population in the state, though he did say at a press briefing last week that discussions with MDOC about the possibility of granting early releases for some inmates are under way.

“Despite these clear indications that the virus is spreading in prison facilities across Mississippi, the governor has taken no action to release people from custody and allow them to return home where they would be better able to protect themselves and others from infection,” Judkins, who is based in Jackson, said in Tuesday’s press statement.

Reducing the prison population, Robertson said, would not only help inmates, but also State prison staff who also have to worry about infection. Prison-reform advocates have long cited severe understaffing in the crowded prisons as a key issue in Mississippi.

“That’s the overarching issue here and the reason that we are even more at risk than lots of other states—because we are so understaffed, and we incarcerate so many people on a per capita basis,” Robertson said. “That’s the number-one priority for the State to look at, and it’s going to be even more important once the Legislature comes back with an even greater challenge to adequately fund MDOC.”

The State already struggles to fund the Mississippi Department of Corrections, and the Legislature will only find it more difficult when it reconvenes in the face of rapidly shrinking tax revenues, he said. Mississippi’s high incarceration rate is a driver of the funding woes, with the state boasting one of the highest rates nationwide. In 2018, the State incarcerated 1,039 residents per 100,000, well above the U.S. average of 698.

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, when Reeves took office in January, a raft of violent and otherwise preventable deaths plagued Mississippi’s prisons, and the governor conceded that reforms are needed.

“We know that there are people in prison today who do not need to be there. We want to fix that,” he said earlier this year, NPR’s Debbie Elliot and Walter Ray Watson reported.

‘Trapped in Legal Limbo’

The currently incarcerated are not the only ones who need relief, though, Robertson said this afternoon. Recently released individuals who are out on probation or parole also face new hurdles in light of the pandemic, he said. Those people are often required to get a job within a certain period of time and must begin paying fines after a certain period, but unprecedented job losses in recent weeks have made the task of finding a job nigh impossible.

Even if recently freed individuals could find a job, getting a photo ID also is not an option for them right now, since all drivers’ license stations across the state are now closed. Nine Mississippi Highway Patrol District Troop Stations remain open, but they only provide sex-offender registry services and commercial driver’s license transactions.

“There’s just a lot of people kind of trapped in legal limbo right now and afraid that they’re going to get sent back,” Robertson said.

But it is within MDOC’s discretion to waive those requirements for now, he said, and opt against incarcerating those people for failing to comply with the impossible. MDOC has not announced a policy change to mitigate those fears, yet, but Robertson said he is “hopeful” that will happen.

‘A Potential Death Sentence’

Last week, immigrants’ rights organizations filed a lawsuit against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement on behalf of seven people at the Adams County Correctional Facility, a private prison in Natchez where the federal government is holding hundreds of undocumented immigrants, including some arrested in last year’s ICE raids at Mississippi chicken plants.

Like FWD.us’ warnings about Mississippi’s state-run prisons, the immigrant advocates told a federal court that the “notoriously overcrowded facility” could prove to be a death trap for medically vulnerable immigrants. Already, nine detainees have tested positive for the coronavirus at the Adams County prison.

Detainees are in danger of “a potential death sentence for a civil immigration violation,” the Center for Constitutional Rights said last week.

Last week, the Mississippi Free Press reported that Salomon Diego Alonso, an undocumented immigrant whom ICE agents arrested during last year’s Mississippi chicken plant raids, was sick with a “severe” case of the virus in a Louisiana detention center and that his family feared he was not getting the treatment he needed. The next day, Noah Lanard reported in Mother Jones that ICE had since moved the ailing man to an intensive care unit.

Many of the inmates who shared a cell block with Alonso, though, had also begun exhibiting symptoms of the virus, Lanard reported.

Cliff Johnson, the director of the MacArthur Justice Center at the University of Mississippi School of Law, said in a statement last week that keeping people locked up in tightly packed cells during a pandemic “is like throwing someone who can’t swim into the Mississippi River and hoping they get lucky enough to wash up on a sandbar before they drown.”

“It’s reckless, and the consequences could very well be lethal,” Johnson said. “All we’re asking is that our clients be given a fighting chance to avoid infection and the complications that they would suffer due to their already compromised health conditions.”

Information on coronavirus prevention measures is available at the University of Mississippi Medical center’s website at umc.edu/coronavirus and at cdc.gov/coronavirus.

The Mississippi Free Press has an interactive map showing diagnosed coronavirus cases across the state and one showing the number of ICU beds in counties across the state.