“Libations poured in remembrance

Balloons released into the sky

Ritual and procession,

Pomp and circumstance

It’s an affair when Black people die.”

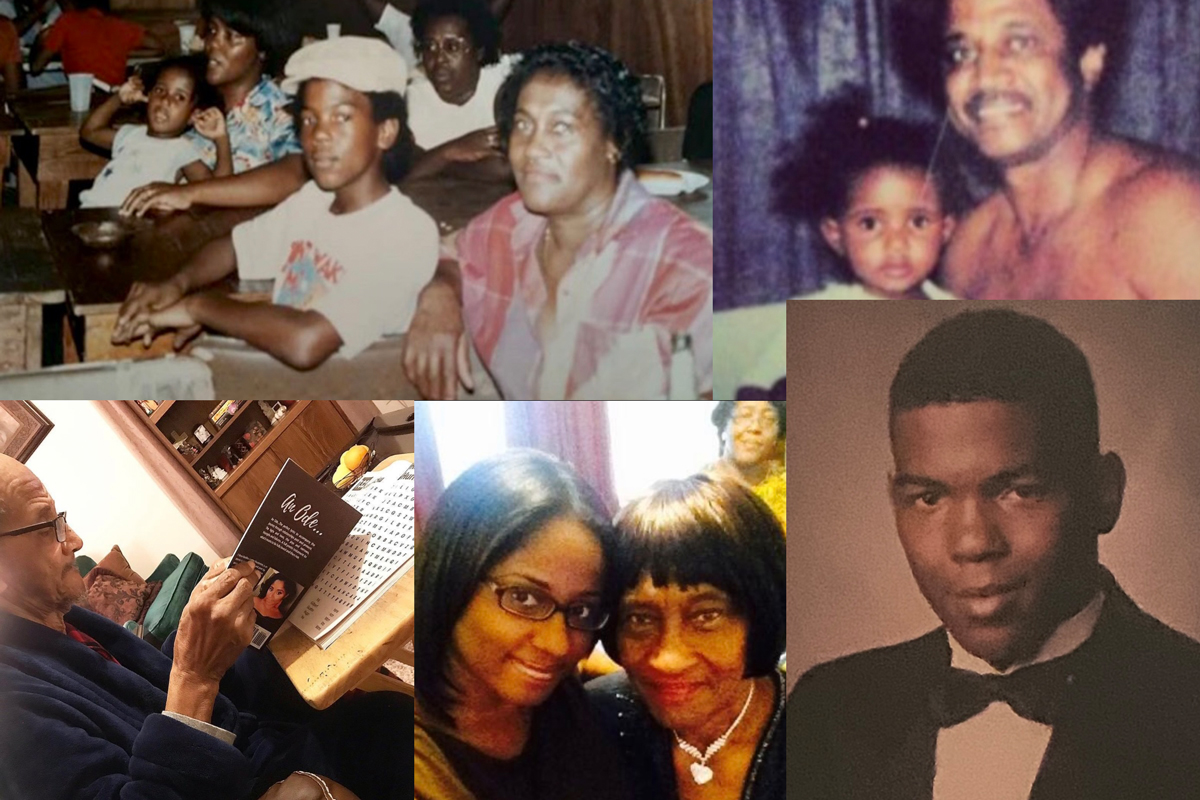

My earliest memory of death was being held in my mothers’ arms as we stood in line to view my paternal great-grandmother’s body for the last time. I was no more than 4 years old, but this final saying of goodbye is forever ingrained in my memory. I vaguely remember various family members leaning over to kiss the lady who I thought was merely sleeping as they took turns gazing at her for the last time. I remember tears flowing freely, the fancy attire and the brightly colored arrangements of flowers decorating the sides of her casket.

I don’t have many memories of what happened next, but I imagine it involved a family gathering where someone brought over chicken fried to perfection, several packs of “soda water” (as it was so affectionately called in Northern Louisiana at the time), and a random assortment of side dishes lovingly prepared by relatives and friends. I do not remember a viable explanation as to why my great-grandmother was now entering into this eternal rest, nor do I remember discussions about her after that day. I just knew that something very important occurred. Even today, more than 30 years later, I can close my eyes and visualize that exact scene.

This was my first experience with death, more specifically Black death, and all the intricacies and formalities that come along with it. So much thought and precision go into the preparation, but one important piece of the puzzle for me has always been what comes next. Despite how crystal clear this memory is in my mind, I can’t remember the mourning, the aftermath or, more specifically, how my relatives handled the grief.

Of course, I was barely school age, so there’s no way to recall those important details, but did I deal with the after-effects of death? I remember the random moments when my mothers’ mind would drift away to some subtle detail of a memory she had with her grandmother, or even how my Big Daddy handled the loss of his mother.

Unfortunately, this lifetime has gifted me many opportunities to experience loss, so I’ve witnessed the different forms death and grief takes within my Black community. With the disproportionality in mortality rates, and the various experiences that come with Black existence in this country, I think the aftermath of how we move forward after experiencing loss is important to discuss openly. It is pertinent that we put as much detail into the grief that follows death since I now realize that Black people refuse to healthily deal with grief after saying goodbye.

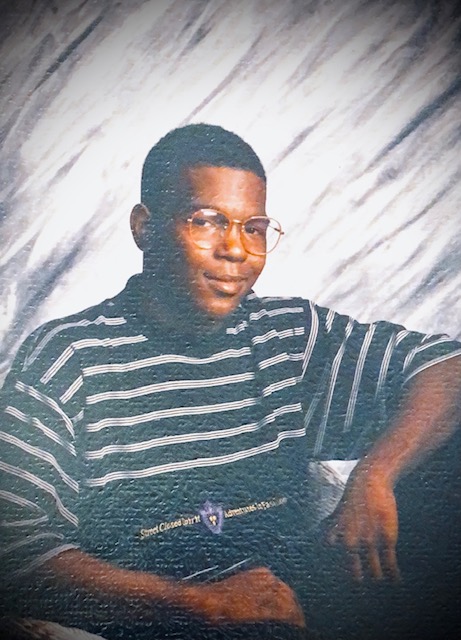

‘Thirty Years Later, I Still Grieve the Loss of my Brother’

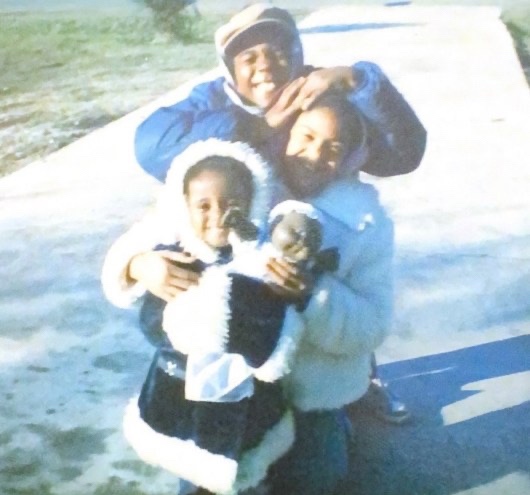

On Aug. 31, 1991, my older brother was murdered when I was 9 years old—He was only 18 years old. This was my very first time experiencing grief. The magnitude of this loss continues to shape my life; 30 years later, I still grieve the loss of my brother. At the time, I did not recognize those feelings, let alone know how to verbally express them, so I retreated into my own world—reading, writing and focusing on perfectionism trying not to cause any extra stress on my parents.

Every member of my family handled the tragedy differently. I saw my mother deal with the brunt of the pain—something I know I could not have managed well if I were her. Actually, she was the same age as I am now, so I can wholeheartedly say I am not made for that type of anguish.

My father’s grief manifested into hyper-protection where our physical safety almost became more important than our feelings. His need to protect took center stage in all our interactions. As for my older sister, who was only one year younger than my brother at the time, her grief was so painful that for years we couldn’t even mention my brother’s name without it causing her unbearable pain.

His tragic death changed the dynamics of our interactions to the point where even today we operate as if the month of August is cursed to always end tragically. Ultimately, I think we all would have benefited from acknowledging and realizing that grief was the real culprit in our lives post tragedy. We seldom took the opportunity to openly discuss how we felt or even express the pain that was a constant factor in our lives. It was as if we were conditioned to keep our heads up and move on without missing a beat. I think many Black households just like mine are expected to handle loss that way, but we all need to realize that grief is a part of the process.

Invisible Anchors and Bottled-Up Memories

Grief is heavy. For me, it feels as if I am sinking with an invisible anchor clasped around my ankle. My day could be going extremely well and then, a song, a date, even just looking out the window and seeing the sun shining down a certain way triggers grief. Now, as an adult I find it easier to reminisce or talk about certain memories with people I’ve lost, but it hasn’t always been so easy.

Sometimes, I want to keep those memories bottled up inside of me as if they are some sort of secret not to be shared. Then other times, I find it soothing to laugh about something funny my grandmother once said or smile about a memory I shared with my daddy who hyped me up like no other.

I still replay the last conversation I had with my uncle before he left this world when he promised me one of the puppies from his dog’s last litter. Preserving these types of memories, albeit painful, is one of the most soothing feelings in the world. I try so hard to be the strong friend or keep it together for the well-being of others, but denying myself the opportunity to reminisce did not and does not serve me.

Expressing anger; being mad at the world for what happened; blaming yourself; wishing there was more you could have done—all of this is normal. But pushing those feelings aside is not. Not allowing yourself to go through the stages of grief can be detrimental to your physical and mental well-being. Science tells us that not properly allowing ourselves to grieve can manifest into several other issues causing physical harm to your body.

This has been a season of loss for so many people, especially Black people—between this ongoing pandemic, the systemic inequity in our justice system, to people just down right stressed out and suffering from the isolation the lockdowns and quarantines caused. Compounding these current struggles with death does not make things any easier. It’s hard, it’s hurtful, and it does not always make sense; however, death and grief are parts of life that we must endure.

Please—Give yourself some grace.

The “strong, Black woman” trope is for the birds; Black men are allowed to cry.

Preserving the memory and legacy of our loved ones is important; Addressing that we are struggling and need time to be OK is our right; It is OK to admit when you are hurting—admission is part of your healing. The harm is when we find ourselves trying to bury ourselves with work or bounce back quicker than we must. Black people deserve the time, the space, the freedom to grieve.

As I think about all the people I have lost in my lifetime, even within this past year, I give myself permission to fully process grief however it comes. And it’s my hope that my Black people will give themselves permission to do the same. Let’s normalize conversations about grief right where we are.

If anyone has any information regarding the murder of Andre Parrott on Aug. 31, 1991, please contact the Houston Police Department.

This piece was published in cooperation with Black With No Chaser, a solution-oriented multimedia platform birthed in Mississippi led by unapologetic and unfiltered minds that think Black and live Black. BWNC documents the all-encompassing Black experience in the United States and throughout the African diaspora.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.