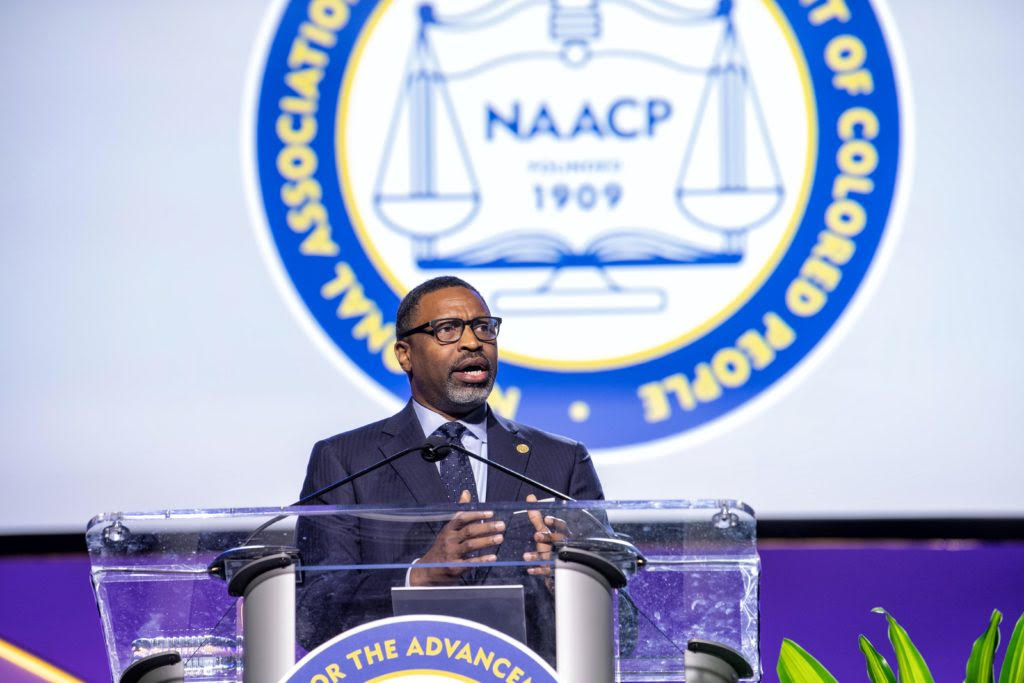

After Hurricane Katrina battered the Gulf Coast in 2005, then-Mississippi NAACP President Derrick Johnson saw first-hand what happens “when government is not operating in a space where support is provided for all communities.”

The now-national NAACP president and CEO evoked the specter of one of the region’s worst national disasters during an emergency telephone town hall on Sunday evening that focused on finding ways to protect vulnerable populations within the African American community as the novel coronavirus outbreak spreads nationwide. Johnson and other national leaders worry COVID-19 could hit black Americans particularly hard—directly and indirectly.

“Our goal as a nation has to be to work to ensure that everyone has that opportunity to reduce the risks of it to themselves, to their families and their communities. And we know that’s not the case in America today and clearly hasn’t been the case during public health crises in the past,” said Dr. Rich Besser, who served as the acting CEO of the Centers for Disease Control where he oversaw the beginnings of the Obama administration’s response to the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 2009.

That disease proved less deadly for the average person infected than the COVID-19 has so far; in countries where the novel coronavirus began spreading before it arrived in the U.S., about 3.4% of those infected have died. Still, said Besser, who is now the president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, COVID-19 will likely share one thing in common with past outbreaks in the U.S.: a disparate impact on people of color.

“These emergencies have always taken a harder toll on communities of color than other communities and that shouldn’t be allowed to happen,” Besser told the estimated 20,000 people who dialed in for Sunday night’s tele town hall.

‘We Want to Make Sure We Are Not Looking at Another Katrina’

Sen. Kamala Harris, an African American Democrat who ran unsuccessfully for her party’s nomination for president before ending her campaign in November, alluded to that history in her remarks.

“We know folks have a long history, a righteous history, of not necessarily trusting these systems, because we’ve not had equal access to medical health and the facilities that would supply that,” the U.S. senator from California said. “So we have to look out for one another, but we also have to be talking to folks about the need to trust medical providers.”

In Mississippi especially, health-care access has been a particularly fraught issue in recent years. Under President Barack Obama’s 2010 Affordable Care Act, the State could have expanded Medicaid to cover about 300,000 more working Mississippians who make too much for traditional Medicaid but not enough for other health-coverage options. Instead, Mississippi’s Republicans leaders have refused to accept $1 billion in federal funds annually to expand the program each year since 2013, leaving many Mississippians—particularly people of color—without access to health care. The lack of expansion has forced several rural emergency rooms to close, unable to bear the costs of so many uninsured patients seeking emergency care.

The current governor, Tate Reeves, rejected Medicaid expansion during his campaign last year for governor, even as Republican opponent Bill Waller Jr. and Democrat Jim Hood both supported Medicaid expansion in Mississippi.

A bill in Congress could help make it easier to test and treat vulnerable populations where health care is lacking during the outbreak, though, if the Senate approves it and President Donald Trump signs it. Early Saturday morning, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which includes free COVID-19 testing, paid family and medical leave, strengthened unemployment insurance, an increase in federal Medicaid funds, and food-security measures.

One of the representatives who backed the bill, African American Democratic Congresswoman Robin Kelly of Illinois, emphasized the bill’s necessity as the coronavirus wreaks havoc on the U.S. economy and strains its health-care and child-care systems.

“We know many in the African American community are food insecure, which is really a concern with so many schools now closing” and children no longer having access to free or reduced price lunches in schools, Kelly said on Sunday night’s call.

Sen. Harris, too, said congressional action is urgent.

“We want to make sure we are not looking at another Katrina,” said Harris, who in 2018 visited New Orleans for a convention, where she praised the city for rebuilding even after the federal government’s mismanagement had devastating effects that overwhelmingly hurt that city’s majority black population.

Surgeon General: ‘I’m Fighting for Black and Brown Communities’

U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, the second black man to hold that position, also joined Sunday’s call. He acknowledged that the U.S. has been slow to test possible COVID-19 victims.

“Our health-care system and the CDC was never designed to have a government-led testing of hundreds of millions of people. The CDC was designed to respond to localized disasters,” Adams said. He added that the country was “always going to need to rely on the commercial industry and private industry” for large-scale testing.

The surgeon general said he believes that the U.S. is reaching a “turning point,” though, and that tests should become much more widely available in the coming week. In the meantime, Adams said, anyone with a cough or fever should avoid going out in public or visiting other people. Still, he encouraged people to use tools like Facetime and Skype to stay connected and “keep spirits up.”

Adams said he is aware that people of color are likely to sustain some of the pandemic’s worst consequences. “I’m fighting for black and brown communities, people who are disadvantaged, and families that need support,” he said.

During the call, Sen. Harris told listeners that the federal government must address the fact that many low-income workers, a group that is disproportionately black or Hispanic, do not have paid sick leave. The senator also highlighted the strain that small black-owned businesses could face.

“When we look at black families that are starting small businesses, there is going to be a real concern that these businesses will have to close due to the economic impact of this pandemic,” Harris said. “I am looking at how the federal government can support (them) through bridge loans that will help small businesses make it through the next couple of months.”

‘It’s Going to Radically Change Lifestyles’

Like Johnson and Harris, Dr. Nicolette Louissaint carries the lessons of Katrina with her. She is the executive director of Healthcare Ready, a nonprofit that organizers set up after Hurricane Katrina to focus on “health preparedness and response” for eventual disasters.

“Our goal is to make sure that we’re really building capacity between disaster and in times of crisis facilitating solutions to help the most vulnerable meet their medical needs in times of disaster and disease outbreaks,” Louissaint said on Sunday night’s call.

COVID-19 is an “unprecedented pandemic,” but it is also one for which her organization has been training and preparing, she said. She urged providers to “lean into technology” and “think creatively” about ways to address people’s needs without meeting face-to-face. Using mail-order systems to deliver prescription medications to vulnerable people, she said, is one tool that can help minimize risk.

“This really is a long haul. This is a sustained event. So we have to be prepared to really address this as a community, because in order to stem the outbreak or flatten the curve, it’s going to radically change lifestyles,” Louissant said.

Not all lifestyle adjustments will work for everyone, though, W.K. Kellogg Foundation President La June Montgomery Tabron said later in the call. She pointed to the waves of Americans who have begun working from home over the internet instead of in often crowded office spaces.

“A third of people in rural communities don’t even have internet access, so the work from home option isn’t even available to them,” she said.

Organizations like hers will have to step in and find ways to “fill gaps” to solve problems like that, Tabron said. Another issue her organization is prioritizing is the 2020 Census.

“It’s extremely important to make sure that these communities that are typically undercounted are counted in this 2020 process because we don’t get another opportunity for a decade,” she said. She added that efforts to promote and gather censuses could prove more challenging because of a lack of face-to-face contact.

Traci Blackmon, a United Church of Christ reverend, brought up another aspect of the coronavirus that is already proving particularly disruptive in many African American communities: the canceling of church services.

“Closing the building does not mean we have closed the church,” Blackmon said. “And that’s important. Language matters, especially in the African American community, where church remains an important part of our lives.”

She suggested “alternative ways of worship,” including live streams and social media groups. Church groups should also begin looking at ways to help displaced workers, people who live alone and may be lonely due to isolation measures, and “the unhoused and unsheltered.” She also implored the spiritual to listen to the counsel of medical experts.

“We can trust God and still trust science,” she said.