For 126 years, a banner based upon the Confederacy’s first national flag and the Confederate battle flag waved atop poles and government buildings, reminding residents of the Blackest state in the nation that white supremacy still ruled in Mississippi. That changed one year ago today when years of work paid off for the Black Mississippians who led the effort to retire the 1894 Mississippi State Flag.

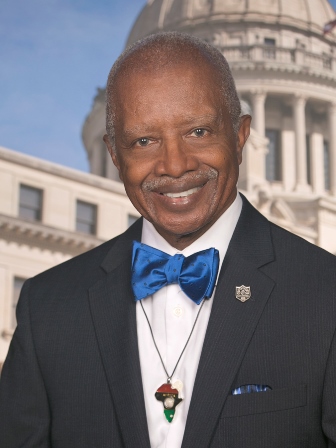

“I feel good,” Sen. Hillman Frazier, a Black lawmaker from Jackson who worked on the flag issue for decades, told the Mississippi Free Press on the anniversary of the Legislature’s historic vote to take the old flag down.

That would not have happened, he said, if not for the COVID-19 pandemic, which cut the spring 2020 legislative session short. After early spring lockdowns, lawmakers in the mostly white, Republican-led Mississippi House and Senate reconvened over the late spring and summer months.

“COVID gave us more time to talk about the issues and have heart-to-heart discussions. So I had time to talk to my colleagues one-on-one. That was important. … Had it been a regular session, it wouldn’t have passed because we wouldn’t have time to get around to talking to our colleagues,” Frazier said.

“We had the chance to educate one another.”

‘Young People Used Diversity To Their Advantage’

Since the Legislature voted to retire the old flag, state and national media have often credited sports leagues like the SEC and NCAA for threatening boycotts of the state unless state leaders replaced the flag. But neither lawmakers nor sports leagues were the primary drivers of change, the Democratic senator said.

“The sports leagues did persuade some people in terms of revenue concerns and not being able to host regional tournaments for some people in our state. That did inform some people. But I think what got our attention was the youth movement,” Frazier said.

“If you notice, during that time, you had Black, white, Hispanic—all different colors came together and showed us where we can go together. Young people used diversity to their advantage and increased their voice. That made their voice strong for building the future of this state.”

In the wake of nationwide protests over the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the deaths of other unarmed Black men and women, such as Breonna Taylor, Mississippians marched and held Black Lives Matter rallies across the state during the summer of 2020. Residents of historic white-flight towns protested racist remarks from local officials, teenagers staged walkouts at high schools, university athletes demonstrated on their campuses and groups of citizens protested on small-town street corners.

On June 6, 2020, in the largest demonstration since the Civil Rights Movement, an interracial coalition of thousands of Black Lives Matter activists marched on Jackson, arriving at the gates of the governor’s mansion. One speaker, Jarrius Adams, presented a list of demands for change for state lawmakers, including a call to change the state flag; months later, he would tell the Southern Poverty Law Center that the flag change was “the proof of our ancestors’ labor.”

On June 6, 2020, in the largest demonstration since the Civil Rights Movement, an interracial coalition of thousands of Black Lives Matter activists marched on Jackson, arriving at the gates of the governor’s mansion. One speaker, Jarrius Adams, presented a list of demands for change for state lawmakers, including a call to change the state flag; months later, he would tell the Southern Poverty Law Center that the flag change was “the proof of our ancestors’ labor.”

By the time of the Jackson protest, though, most public officials had given little reason to think they were ready to adopt a new flag. Less than a week later, on June 12, Gov. Tate Reeves reiterated his opposition to the idea, telling SuperTalk radio host Paul Gallo that he “would be surprised if there are an adequate number of votes” to change the flag. The governor claimed such a legislative effort would prove divisive and make it difficult for Mississippians to unify.

Gov. Reeves Initially Opposed Flag Change

“There’s an awful lot of people who ran for office in 2019, myself included, who told the people of our state that the only way in which the flag should change is if the people of Mississippi decide to change it,” Reeves said. “And the reason that’s important to me, Paul, is that … I firmly believe the people of Mississippi at some point may want to change the flag. But when they do so, everyone is going to have to move on. We’re going to have to come back together as a state. And the only way that can happen in my opinion is if the people decide to do it.

“If it’s considered to be a backroom deal by politicians in Jackson, I don’t think the state is going to come back together in any short order, and I really don’t think in the long-term that’s a good thing for Mississippi.”

But 12 days later, the Mississippi Economic Council released a poll showing that, for the first time, a majority of Mississippians, by a 55-41 margin, supported changing the state flag—a reversal from a 2019 MEC poll that 54% of voters favored keeping the old design.

“In the nearly 20 years we have held the position of changing the state flag, we have never seen voters so much in favor of change,” MEC President Scott Waller said in a statement on June 24, 2020. “These recent polling numbers show what people believe, and that the time has come for us to have a new flag that serves as a unifying symbol for our entire state.”

The development represented a drastic shift since 2001, when 64% of voters opted to keep the Confederate-themed flag in a statewide referendum. That vote came on the heels of a 2000 governor-appointed commission that studied the possibility of changing the flag, touring the state to get input from residents in different towns and counties.

Black members of the commission often faced verbal abuse at those hearings as angry white residents who opposed changing the flag made their case.

‘To Secure The Supremacy Of The White Race’

At one November 2000 flag hearing in Jackson, a teenage girl wearing a shirt with a large Confederate X across it introduced herself as a grocery-store worker.

“I do work with blacks, and I have several—not just one or two—but several friends who are black,” she began. Those friends, she said, had differing views about what Mississippi should do about its flag.

“One person said, ‘Where would the slaves be today if not for slavery? They’d probably still be in Africa enslaved today if not for slavery,’” the girl offered before plowing through the ensuing chorus of groans to relay another black friend’s alleged thoughts.

“One person asked me to point out that most of the African American race living in America today got their last name from their masters,” she said. “Are you prepared to give up your last name? I don’t think you are. Because if you get my flag, I will get your name.”

Patrick Jerome, then a white 19-year-old white Millsaps College freshman, also spoke up in defense of the flag.

“Those who want to take down this flag of Mississippi are the racists. They’re the ones that think so little of minorities that they love to give them handouts like affirmative action,” Jerome told the packed auditorium. His words drew boos from black audience members mingled with approving cheers from white ones who were holding state flags or decked out in Confederate attire.

Almost 20 years later, though, Jerome was one of the Mississippians who had since changed his mind by June 2020. He said his earlier views were partly the byproduct of his education at an all-white academy and growing up hearing only white conservative points of view.

“Oh man, I looked like a goddamn supervillain,” he told the Mississippi Free Press in June 2020 as he explained how his views evolved. “Obviously, we’re a state that’s 38% black, and we still fly a flag that’s a middle finger to all of those people. The people who use it, the people who fly it, they’re not good people. If they say it’s about heritage, it’s a heritage of running an authoritarian police state to keep people enslaved.”

After the end of slavery, newly free Black Mississippians made significant civil rights gains. But with Reconstruction’s end, Mississippi’s white leaders radically remade its Constitution in 1890 with the goal of disenfranchising black voters, implementing a system of Jim Crow laws that included literacy tests, felony voting disenfranchisement and poll taxes.

In a convention hall where state officials plotted out the new constitution that September, one state lawmaker, J.H. McGehee from Franklin County, gave a rousing speech to his fellow lawmakers’ delight.

“I will agree that this is a government by the people and for the people, but what people? When this declaration was made by our forefathers, it was for the Anglo-Saxon people. That is what we are here for today—to secure the supremacy of the white race,” he said.

Black Activists Spent Decades Fighting For New Flag

Following the adoption of the state’s 1890 Jim Crow constitution, the state’s white supremacist leaders adopted the Confederate-themed flag in 1894. The design provoked few challenges during most of the century that followed, with no major outcry until the decades after the Civil Rights Movement achieved success in overturning much of the Old South’s Jim Crow legal structure. As recently as the early 1980s, the Mississippi NAACP remained split on whether or not it was worth fighting for a new, less offensive symbol.

But John Hawkins, the University of Mississippi’s first black cheerleader, forced the issue of flags and Confederate imagery in 1983 when he refused to partake in the tradition of carrying and distributing rebel flags at Ole Miss football games, leading the university to eventually ban the ubiquitous flag from its official sports festivities.

Concerns over the state flag’s own Confederate imagery soon bubbled to the surface. In 1988, then Mississippi House Rep. Aaron Henry, a longtime NAACP leader with a storied civil rights legacy, introduced his first bill to repeal the Mississippi flag. The House never brought it to the floor for a vote, even though Henry reintroduced it twice more in 1990 and 1992.

In 1993, the Mississippi NAACP filed a lawsuit, arguing that the flag violated Mississippians’ constitutional rights “to free speech and expression, due process and equal protection as guaranteed by the Mississippi Constitution.”

After a lower court dismissed the suit, the NAACP appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court, where, in 2000, the state’s top judges discovered an unexpected twist: Unbeknownst to state officials for nearly a century, apparently there was no official state flag. Lawmakers, in an apparent oversight, had nixed the flag when it revamped the state code in 1906 when they failed to include the state flag and coat of arms sections in the new version.

Still, the State’s high court agreed with the lower court that the NAACP had no case because the flag, while offensive, “does not deprive any citizen of any constitutionally protected right.”

The discovery that Mississippi in fact had no official flag prompted then-Gov. Ronnie Musgrove’s decision to appoint the 2000 state flag commission.

The commission members included Sen. Hillman Frazier, who told the Mississippi Free Press today that he recalled the hearings as “very hostile and contentious.” But even back then, he said, he could see the seeds of change bearing fruit.

“You had a very unruly crowd. They were very nasty with very personal attacks, sending out threats and things like that,” the Jackson lawmaker said. “But during a hearing on the coast, I received a note from one young lady. She was apologizing for some of the behavior of the folks who wanted to retain the old flag. Although she also wanted to retain the old flag, she didn’t like the ugliness she saw during those hearings.”

‘I Thought I Would Never Live To See This Flag Come Down’

After a white gunman with an affinity for the Confederate flag massacred nine black members inside a Charleston, S.C., church in 2015, that state’s legislative body voted to remove the Confederate flag that still flew on the South Carolina capitol grounds. The killer cited the Council of Conservative Citizens, a white supremacist group with roots in Mississippi, as one of his inspirations as he spouted white supremacist language similar to that used by McGehee during the 1890 flag debate.

In Mississippi, a number of towns and counties along with the state universities responded to the South Carolina massacre by removing the Mississippi state flag from its flag poles. A number of white state officials, including then-Attorney General Jim Hood, a Democrat, and House Speaker Philip Gunn, a Republican, publicly voiced support for changing the flag, though most white lawmakers remained silent or outright opposed change.

Gunn is from Hinds County, where 64% of voters supported changing the flag in the 2001 referendum. A majority also voted to change the flag in neighboring Madison County, which is heavily suburban and majority white. But as recently as January 2014, Gunn declined to state a position on the issue when asked about it by the Clarion-Ledger.

In the ensuing years, though, activists who supported changing the flag would only make their voices louder. In 2016, Mississippi-born rapper and activist Genesis Be drew national attention to the state flag when she protested on a New York stage by draping a Confederate flag across herself and noose around her neck.

Pro-1894-flag activists who had weekly protested the University of Southern Mississippi’s decision to get rid of the old flag suddenly had to share the campus entrance where they demonstrated with Black Lives Matter activists in 2017. Protesters burned a state flag outside the governor’s mansion in 2018.

With a national race reckoning ongoing in June 2020, Gov. Reeves, who followed in his recent predecessors’ footsteps by declaring April 2020 “Confederate Heritage Month” (and again this year), continued to warn late into the month that “any attempt to change the current Mississippi flag by a few politicians in the Capitol will be met with much contempt.”

Kylin Hill, a Black star running back at Mississippi State University, quoted Reeves’ tweet with a warning of his own.

“Either change the flag or I won’t be representing this State anymore & I meant that .. I’m tired,” Hill wrote.

In the days that followed, lawmakers who had either been silent or who once vocally opposed changing the flag announced that they would back an effort to retire the old flag.

On June 28, 2020, Mississippi House Rep. Jason White, a Republican from West, introduced a resolution to change the flag.

“The eyes of our state, the nation, and indeed the world are on this House this morning. History will be made here today. … Whether we like it or not, the Confederate emblem on our state flag is viewed by many as a symbol of hate. There is no getting around that fact,” he said.

That same day, the Mississippi House voted 85-34 to retire the 1894 flag and set up a commission to design a new one.

Hours later, Sen. Barbara Blackmon, a Jackson Democrat whose husband, Rep. Ed Blackmon, served alongside Frazier on the 2000 flag commission, spoke on the Senate floor. She recalled tears turning into icicles on her face one frosty cold January day in Washington, D.C., as she watched Barack Obama take the oath of office in 2009.

“Just as I thought I would never live to see a Barack Obama, I thought I would never live to see this flag come down,” she said minutes before the Senate voted 36-14 to change the flag.

Reeves Decried ‘Mobs’ While Signing Flag Law

Two days later, Gov. Reeves, in a reversal from his stated position in the 2019 campaign, signed the resolution.

“Frankly, I’m not all that concerned about the eyes of the nation,” he said. “I do care, however, about looking in the eyes of every one of my neighbors—and making sure they know that their state recognizes the equal dignity and honor they possess as a child of the South, a child of Mississippi, and yes, as a child of an Almighty God.”

During the same speech, Reeves criticized Black Lives Matter protesters in other states, characterizing them as “mobs tearing down statues of our history—north and south, Union and Confederate, founding fathers and veterans.” This year, on the penultimate day of the Confederate Heritage Month he had declared for the second year in a row, Reeves denied that systemic racism exists in the United States.

Former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Rueben Anderson, the first Black member of the state’s high court, led the commission that chose the new flag design featuring a magnolia. On Nov. 3, 2020, 73% of Mississippi voters cast ballots in favor of adopting the new flag. Majorities in 80 of the state’s 82 counties voted for the new design.

In Greene County, voters rejected the new design 54-46, while George County voters disapproved 51-49. Though the state overall is about 38% Black, white residents comprise 73% of the population in Greene County and 89% in George County.

Earlier this year, a group of 1894 flag supporters began collecting signatures to put the issue on the 2022 ballot, in hopes of offering voters a chance to reinstate the old flag. That effort is dead, though, after the Mississippi Supreme Court last month nullified the state’s ballot initiative law.

‘We’re Going To Have To Listen To Young People’

Calvert White, one of the Black Lives Matter Mississippi activists who called for the flag to change last summer, credits the flag change to no one individual.

“It was a synergy of young energy and older wisdom, honestly,” he told the Mississippi Free Press in an interview today. “I cannot narrow it down to a handful of people. It’s a thread that has passed through generations, involving many great organizers and citizens.”

To White, the dam breaking on the state’s flag was a victory of attrition: incremental, intergenerational change—the fruits of decades of sustained efforts.

“It’s been a great struggle by many, many people before us—before the Jarrius Adamses, the Maisie Browns, the Arekia Bennetts of Mississippi,” White said, referencing other young activists instrumental to last summer’s statewide protests.

Today, Sen. Frazier said that the 2020 flag change and the young Mississippians who were instrumental in that cause give him hope for the future.

“When the young people had the big rally in the City of Jackson peacefully asking for change, that kind of forced all of us as legislators to come together. … They don’t want to leave the state; they want to stay here and make it better,” the Jackson lawmaker said. “So they made it better by participating in the rally they had in Jackson and they made it better by contacting their legislators.”

Taylor Turnage, one of the organizers of the 2020 Black Lives Matter march in Jackson, told the Southern Poverty Law Center last year that she and other activists “were tired of being silent.”

“Nothing will get changed unless you go out there and show … that people in the state actually want change,” the SPLC quoted Turnage saying after voters adopted the new flag last November.

The peacefulness of the 2020 protests in Mississippi, Frazier said, was a marked contrast from the loud, often angry voices that characterized the 2001 flag debate.

“Those loud voices can intimidate some of the lawmakers—and did back in 2001,” he said. “But in 2020, they were trying to get us to see that we can obtain this peacefully as opposed to what happened in South Carolina.”

The senator said he and his fellow lawmakers should continue to pay attention to what Mississippi’s youth are saying.

“I feel optimistic about the future,” he said. “We’re going to have to listen to young people and let their voices pave the way.”

Correction: This story originally stated that Sen. Barbara Blackmon served on the 2000 flag commission. She did not. Her husband, Rep. Ed Blackmon, did.

State Reporter Nick Judin contributed to this report.

Read the MFP’s full series on how the Mississippi flag finally changed in 2020:

1. Black Mississippians Paved The Way For State Flag Change A Year Ago Today

2. ‘No Compromise’: How Crystal Welch Changed The State Flag Debate In 19 Days

3. Young Black Activists Helped Change The State Flag. They Intend To Change The State.