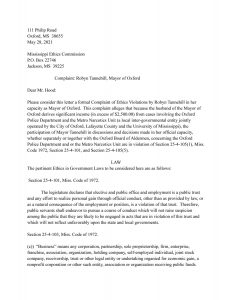

OXFORD, Miss.—Oxford Commission on Police Transparency member Barbara Phillips has asked the Mississippi Ethics Commission to investigate Mayor Robyn Tannehill’s potential conflicts of interest between her police-related decision making and her husband’s defense of clients that the same law-enforcement organizations have arrested.

“[B]ecause the husband of the Mayor of Oxford derives significant income … from cases involving the Oxford Police Department and the Metro Narcotics Unit …, the participation of Mayor Tannehill in discussions and decisions made in her official capacity, whether separately or together with the Oxford Board of Aldermen, concerning the Oxford Police Department and or the Metro Narcotics Unit are in violation of Section 25-4-105(1), Miss. Code 1972, Section 25-4-101, and Section 25-4-105(5),” Phillips’ complaint alleges.

Section 25-4-101 of Mississippi Code 1972 says public officials should act in a way “… which will not raise suspicion among the public that they are likely to be engaged in acts that are in violation of this trust and which will not reflect unfavorably upon the state and local governments.” The other two codes outline the acts to which this law refers.

The recently reelected Mayor Tannehill “oversees the appointment/retention of personnel, manages human resources issues and is involved in budgetary and administrative decisions related to the functioning of OPD … routinely reviews videos of OPD stops and arrests in her oversight role as executive, both as a means of personnel oversight as well as in response to citizen complaints,” Phillips’ complaint states, adding that Tannehill “created a Commission on Police Transparency and has attended meetings where the oversight of OPD is a recurring topic of conversation.”

The complaint alleges that Tannehill shared confidential government information with her husband that was not then known to the public.

“On April 7, 2021 Rhea Tannehill revealed in conversation with members of the local Bar (Association) that he was aware of missing funds from the Metro Narcotics Unit, referring to such as ‘old news,’ though such information had only been disclosed to the public in reporting published the day before,” Phillips, a retired lawyer, alleged in her complaint, referring to an April 6, 2021, Mississippi Free Press investigation about the narcotics unit.

“This disclosure creates, at minimum, public suspicion regarding the sharing of non-public information by Mayor Tannehill,” Phillips’ complaint added.

Finally, the complaint refers to a previous Mississippi Ethics Commission decision, Advisory Opinion 16-010-E, which deals with county supervisors maintaining law practices. The opinion calls for the affected officials to recuse themselves from certain law enforcement-related activities, among other things, to avoid violating Section 25-4-101 of Mississippi Code 1972.

A Question, Already Answered

“In 2016, I requested an ethics opinion regarding the matter named in her complaint,” Mayor Tannehill said in an email in response to a Mississippi Free Press interview request regarding Phillips’ complaint. “If you locate this advisory opinion, you will note that this issue has already been addressed by the Mississippi Ethics Commission.”

The Mississippi Ethics Commission confirmed the legality of Tannehill’s husband’s law practice in the 2016 opinion, shortly before she took office as mayor. The decision, issued in 2016, answered this question: “May the mayor’s spouse who is a member of a law firm represent private parties who appear in municipal court?”

The ethics commission found that a mayor’s spouse could represent private parties in court, but “Section 25-4-105(1), Miss. Code of 1972, prohibits the mayor from using his or her official position to obtain, or attempt to obtain, a pecuniary benefit for the mayor’s spouse and the law firm,” the decision said. “However, a mayor will have little opportunity to violate that provision since the spouse will not be paid by the city.”

“I would say that question is very different from the question I’m putting before the Ethics Commission,” Phillips said in an interview in response to Tannehill’s statement that her ethics question had already been answered. A University of Mississippi bio shows that Phillips had previously taught in the UM law school and was a partner in a San Francisco law firm focusing on voting rights. Also a critic of police militarization, she was previously staff attorney with the national Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law in its Mississippi office and Washington, D.C.

Phillips explained that she is concerned that Rhea Tannehill allegedly indicated that he had non-public knowledge of missing funds from the local narcotics unit prior to the Mississippi Free Press story in April. If that knowledge could benefit one of his clients in some way, Phillips argues, then the mayor may have acted improperly if she shared this information with her husband—which would violate the Ethics Commission’s earlier ruling.

The mayor’s original request to the commission, in its more detailed form, asked specifically if she should recuse herself from matters specifically related to the court, not the police department. “If I were serving as Mayor, would there be any conflict with my husband practicing in City Court and should I recuse myself on matters that involve the City Court department due to my husband’s practice of law involving cases before our City Court?” Tannehill asked in her ethics inquiry.

The ruling states that “if the requestor obtains non-public information as a result of her position as mayor which could benefit a client of her husband’s firm, she would be strictly prohibited from disclosing such information to her husband or his client.”

Rhea Tannehill, the mayor’s husband, was unaware of the complaint when the Mississippi Free Press called him on Friday, May 28. He declined to comment on the record.

An Unofficial Police Transparency Meeting

Barbara Phillips’ complaint comes after months of meetings of the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency, a panel of citizens that the Board of Aldermen members and the mayor appoint.

The June 16, 2021, meeting of the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency was cancelled via a June 10 email from Oxford Police Chief Jeff McCutchen and has yet to be rescheduled.

Still, Phillips reached out to her fellow commission members to organize a time to meet anyway, and Rev. Eddie Rester, another commission member, secured a room for the group to meet at the Oxford University United Methodist Church.

Phillips gathered with a handful of commission members alongside members of Tupelo’s Police Advisory Board, Indivisible Northeast Mississippi, the Tupelo NAACP, and several other organizations and interested community members in the church’s conference room on June 16.

“I agreed to go before (the original meeting) was cancelled,” Tupelo Police Advisory Board member and former Chaplin Ron Richardson later told the Mississippi Free Press. “I was interested to hear the lady, the lawyer, talk about what the role is with that group in Oxford, compared to the advisory board that I’m a member of here in Tupelo.” He was referring to Phillips.

One commissioner left in opposition to the press—a single reporter from the Mississippi Free Press—being present at the meeting, shortly after it began.

“It was interesting to me that the person, the lawyer, who discovered that you were there was uncomfortable being there with a reporter present, and so he got up and left,” Richardson told the Mississippi Free Press. “And if a lawyer, a well-educated lawyer, is uncomfortable with the presence of a reporter in a meeting, how much more uncomfortable is a citizen of the community who comes to speak to an advisory board about a problem he’s having out in the community, in the presence of so many police officers?”

“I was amazed in the meeting that that connection was never made,” Richardson added.

It was the first meeting of the commission, however unofficial, in which the diverse group of members were able to set their own agendas, as the mayor and police chief usually set the agenda and run the meetings. All seats were filled at the conference table, with almost all the against-the-wall chairs taken as well.

A Citizens’ Commission Without Power

At the unsanctioned meeting, commissioners and visitors discussed how Tupelo’s Police Advisory Board works compared to the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency.

The Tupelo Board of Aldermen established its Police Advisory Board in April 2017, after Tupelo police officer Tyler Cook fatally shot a 37-year-old father of four, Antwun “Ronnie” Shumpert, during a 2016 traffic stop for what police later said was an outstanding warrant. Cook released his police dog on Shumpert after he ran away and hid—where exactly he hid is contested—and then shot him four times, following a physical altercation.

The police account of the incident and the account Shumpert’s family lawyer presented vary widely, but photos of Shumpert’s autopsy show a large wound in the groin, three large scratches on his back, and his bottom teeth bent back, the Clarion Ledger reported.

In Tupelo, the Police Advisory Board has a chairperson and is a permanent feature of the city since being established three years ago. But in Oxford, the members cannot have real meetings about police accountability, members complain.

“We have no authority, and we have no structure,” Phillips told the Mississippi Free Press about the sanctioned commission meetings. “We do not have a chairperson of the commission. We have no authority to set the agenda for our meeting.”

It is unclear if the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency will exist after the 18-month term to which its members were originally appointed in September 2020 following public calls for police reform. The commission’s purpose is to facilitate communication between local law enforcement and the community, as the original information sent to commission appointees stated.

“The meetings are controlled by Jeff McCutchen, the chief of police, and the mayor,” Phillips said. “They say OK, today we’re gonna talk about, you know, and Jeff does a PowerPoint presentation. We are asked if we have any questions, and that’s it.”

Richardson described that, despite the Tupelo board having more independence than its Oxford counterpart, it often faced a blue wall of defensiveness.

“Anything that was said that was a form of a complaint for the community was taken as a criticism of the police department, rather than some input that would be helpful to them,” Richardson said. “And I never wanted to come across like I was against the police department—I am very much for the police department—but … I found out that police are pretty defensive of their knowledge of how to run a police department, and (believed) the board really had no business telling them what to do.”

Two Mississippi Cities, Two Police Encounters

Attendees of the unsanctioned Oxford meeting shared stories about police conduct in their towns. They talked about Wesley Wells and Dominique Clayton, in particular.

Wesley Wells is an African American business owner in Tupelo who was stopped on March 16, 2021, while exercising at Barnes Crossing, near the mall, the Daily Journal reported. Arresting officer Blake Hudson can be heard, in footage then-Mayor Jason Shelton released, dispatching that he is going to approach “a white male in front of Dick’s Sporting Goods.” Wells, who is not in fact white, was arrested and detained for about 15 minutes before being released.

In 2019 OPD fired Oxford police officer Matthew Kinne after he allegedly murdered local mother-of-four Dominique Clayton. Kinne still awaits trial. The two police officers who submitted their resignations to the Oxford Police Department following Clayton’s death, Collins Bryant and Ryan Winters, have not been charged with any wrongdoing.

Earlier this year, a Mississippi Free Press investigation by Christian Middleton found that upwards of $34,000 went missing from the Lafayette County Metro Narcotics Unit, which is based in Oxford. Not long after this report, Oxford lawyer Kevin Frye used the investigation, alongside arrest statistics the Oxford Police Department released, in a court filing to show a wide disparity between drug arrests and prosecution of people of different races and, ultimately, won his Asian client a plea deal. The two white men arrested alongside his client in 2018 were finally served within days of Frye’s recent filing about racial disparities and alleging selective prosecution of his client, considering that the white men were treated differently.

Most attendees at the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency meeting expressed discontent with the current state of the advisory group.

“I’d like to see a more open discussion,” attending community member Martha Scott told the Mississippi Free Press. “I’d like to see law enforcement being more community engaged. … I feel like we just hear after the fact.”

“I am still extremely concerned that the drug-enforcement wing of the police here in Oxford still has their confidential-informant program going,” Scott said, explaining that it affected “a friend of (her) son, whose life was hurt terribly by that.” The dangerous confidential informant program was the subject of a 2015 Buzzfeed investigation and later “60 minutes” episode.

Only one attending commissioner, John Abernathy, said he was generally satisfied with the commission’s progress, but not all commissioners were present at the unofficial meeting.

Not a ‘Go Get the Police’ Kind of Thing’

Linda Bishop, the former president of the local League of Women Voters chapter, was a community member attending the June 16 meeting. Her LWV chapter had written a letter to the city asking for a review board for policing practices in June 2020 in the wake of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd.

The two-page letter warned that Oxford had the potential to become another Minneapolis or Ferguson, as LWV put it, and called for the “elected leaders and all the citizens of Oxford and Lafayette County to join our voices for racial equality and justice in our community. Because there is a problem in our community.”

The LWV letter then said pointblank: “Our black citizens don’t feel welcome in many public places in our community. Our black citizens have been stopped and questioned while walking on the Square. Our black students know which bars on the Square don’t welcome them. Our black citizens have been stopped in their cars without cause. Events catering to black citizens are policed differently than events for white citizens.”

Two months after that letter, a Mississippi Free Press investigation revealed sexist and racist University of Mississippi emails between a donor and a journalism dean showing in detail how some white men were viewing, photographing and characterizing Black students on the Square.

The LWV letter called for the development of citizen advisory groups “to work with our Oxford Police Department and our Lafayette County Sheriff’s Department to review current policies and procedures on their Use of Force, Training and Education, Hiring, and Community Policing.”

The League wrote that these groups must represent the demographics of the community—about 30% of Oxford residents do not identify as white—and regularly update the public on their work toward evidence-based guidelines and new policies and procedures. The LWV demanded that the public hear regularly about “what (policing) policies are outdated or flawed, what needs to change, what is the proposed change, was it adopted, why or why not? Transparency during this process is key.”

Linda Bishop emphasizes that the accountability effort is not anti-law enforcement. “I don’t see this as a ‘go get the police’ kind of thing,” Bishop told the Mississippi Free Press. “I would like the commission to be a support group for not only that chief, but also for the rank and file officers there. I would like for them to know that there is a board of citizens that want to support them.”

“But,” she added, “I also think it’s important that the public knows that there is an organization that will help hold police accountable … the same way that we have a school board that holds school administrators and their fellow teachers and administrators accountable.”

‘I Don’t Like This War on Drugs, But …’

Mayor Tannehill, OPD Chief McCutchen and Lafayette County Sheriff Joey East participated in a Zoom meeting centered around national issues of police brutality and racial injustice in 2020, an email from Tannehill to commission members stated.

“City leaders feel called to take proactive measures to make sure that we are all serving our community in the best, and most ethical way possible,” Tannehill’s email said about the conversation, which the Oxford-based Conversations for Change hosted.

“We anticipate the commission will issue recommendations, and we are open to hearing them,” Tannehill said in her Sept. 8, 2020, email, which thanked commission members for accepting their positions. “We welcome your honest input and will do our best to be as transparent as possible as we address issues and topics together. … We are committed to positive change.”

Tannehill—who first ran for mayor as a Democrat but switched to run as an independent before her recent reelection—sends mixed messages publicly on policing issues, specifically regarding drug enforcement.

The Mississippi Free Press reported in May that Tannehill endorsed the controversial Metro Narcotics Unit at an April 27, 2021, League of Women Voters of Oxford/Northern Mississippi mayoral forum, after a question about this publication’s investigation.

“You know, I have to say, I’m not against Metro Narcotics,” Tannehill said. “I’m against drugs in our community. Metro Narcotics is fighting drugs in our community.”

The mayor then dropped a seemingly contradictory message on the “war on drugs.”

“I don’t like this war on drugs,” Tannehill said. “But as long as drugs are being used and sold and purchased in Oxford, Mississippi, there’s going to be a need for drug enforcement. That’s the reality. It’s a bad thing that we have to have it, but it’s a good thing that we do. We just need to do it the right way.”

“So, we’re always open to doing things the very best way, and open to hearing criticisms and suggestions, but right now the war has to be fought whether we like it or not.”

U.S. Policing Citizen Review Boards: A Mixed Record

Civilian review boards of police conduct have a mixed record of success, transparency and independence. Most vary from state to state, or even from city to city as is true in Mississippi, from Oxford, to Tupelo, to Madison County.

In New York City, the Citizen Complaint Review Board can investigate claims and hold trials, making recommendations to the police commissioner on what actions to take. The commissioners are not required to follow these recommendations, however, a source from the CCRB told the Mississippi Free Press. The CCRB has drawn loud complaints over the years due to the toothless nature of the group.

In recent months, Maryland has passed new police reform legislation, overriding the veto of Gov. Larry Hogan and putting the state at the forefront of law-enforcement reform. The laws ban no-knock warrants in situations where a person’s life is not in danger and outside the hours of 8 a.m. through 7 p.m., among other stipulations.

Maryland’s reforms, when enacted, will make it one of just a few states that allow the public to view police disciplinary records. Prior to the passage of this law, not even prosecutors were able to access this information, let alone citizen advisory boards.

Mississippi does not allow public viewing of police disciplinary records. It is one of 23 states that regards these records as confidential, according to a New York Public Radio investigation. This means that review boards like that of Tupelo and Oxford cannot view internal disciplinary records from the police department.

Several city commissions are written into Oxford law, like the Parks Commission, the City Planning Commission, the Downtown Parking Advisory Commission and the Historic Properties Commission. The City of Oxford’s code of ordinances lays out the expectations of the commissions, who can serve, who appoints them and for how long, what the commission’s purpose is and the responsibilities of the commission’s members.

Oxford’s Affordable Housing Commission is in the process of including its organization in city ordinances, having had its first public hearing on June 15, 2021. Despite not yet being represented in the city’s ordinances, the commission already had a chairperson and vice chairperson who were able to organize the hearing, the June 15 presentation at the Board of Aldermen meeting showed. The housing commission has one more public hearing before the Board of Aldermen will vote on whether to modify the city code to include it, which would grant the housing commission members the ability to perform certain duties as a board.

Barbara Phillips says it is time to make the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency more transparent itself.

“The public has never been invited to a commission meeting,” Phillips told the Mississippi Free Press on May 28. “But I am informed by people who know about the laws of the State of Mississippi that if this is a commission formed by a public entity, the Board of Aldermen and the mayor, that our meetings are, in fact, public—even though we don’t invite anybody to them.

‘“So with that understanding, I am encouraging people to come to our next meeting.”

The next meeting of the Oxford Commission on Police Transparency will be the rescheduled official meeting that should have occurred on June 16, but a date has not yet been announced.