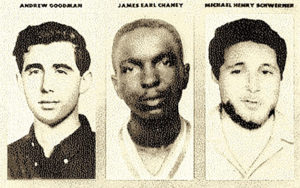

I went to James Chaney’s grave last weekend. His tall tombstone faces a rural road south of Meridian that bends sharply just before the cemetery. It’s not unlike the curve in the country road north of Meridian in Neshoba County where local white supremacists shot the Mississippi native and two other young adults from New York when I was a toddler there in 1964.

It was a pilgrimage I’d never made, but I had long heard that Chaney’s gravesite and tombstone were defaced repeatedly in Lauderdale County. As if it wasn’t enough that a gang of Klansmen, including law enforcement, from Meridian and my hometown of Philadelphia had held them in the city jail under false pretenses, then chased their car down as they headed back South, shot them pointblank and buried them under a dam-in-progress near the Neshoba County fairground, while conspirators burned their station wagon on the other side of the county in Bogue Chitto swamp.

Evil hate covered a lot of Neshoba ground on Father’s Day, 1964.

The lynch mobsters from my town were all well-known names during my childhood, before and past the murders, but not for being murderers but as upstanding citizens, at least among local white folk—Sheriff Lawrence Rainey who had already gotten away with executing a young Black man; Deputy Cecil Price who repaired my birthstone ring and my mama’s watches after a short stint in federal prison; Billy Wayne Posey who pumped my daddy’s gas at the west-end Phillips 66 and gave me a pack of Nabs each time; Edgar Ray Killen, a family friend who I’m pretty sure Ancestry.com will confirm was kin to me when I get around to checking. In fact, they were folk heroes for many white people.

Then there was wealthy businessman Olen Burrage who donated the burial ground for Chaney, Andy Goodman and Mickey Schwerner, and the bulldozer driver Herman Tucker was the daddy of a good friend in the Neshoba Central flute section. My school bus used to stop in front of their house, years past the three bodies being dug up nearby.

By summer 1964, James Chaney was also known in our parts, but as a Black Meridian “boy” trying to “stir up race trouble” (as if killing, terrorizing and segregating Black people with legal impunity wasn’t exactly “race trouble”). But Chaney’s efforts were, in fact, good trouble for future generations like all of us, if not for him and his family, including an infant daughter. His fight for full American status—equal treatment, quality education and voting rights for himself and fellow Black Americans—cost Chaney his life and his family’s security.

Decades later, I would listen to his then-adult daughter Angela say that her family hid her for years after white Mississippi murdered her father and then blamed “the three boys” as racists insisted on calling them (at best) for making them do it. That is, Chaney’s family didn’t want the same type of monsters to come after his infant daughter.

Just sit for a while with that level of fear and evil.

‘Being Segregationist Comes in Many Flavors’

Standing before James Earl Chaney’s gravesite on a beautiful December day—his also-activist mama Fannie Lee is now buried right next to him—I could see the faint residuals of the defacement of his tombstone I’d always heard about: mostly erased markings around his small photo at the top.

I thought of the ingrained anger, passed down for generations (still) of so many white people hellbent on feeling superior to people with a darker skin tone as if, somehow, such a constructed racial caste improves their own lives, instead of the opposite effect. I again considered the tragedy of descending from people who committed and/or justified the brutality of enslaving people and then, even after the evil practice legally ended, defiantly passed the same sick logic and internalized fear down to future generations.

We see the legacies all around us, whether it’s in those who join the Proud Boys and carry tiki torches while defending Hitler and the Confederacy’s cause and use “1776” as a code for white supremacy; those who teach their children that Black people are more violent, or whatever, and then claim innate differences as the reason; or doctors who give disparate care to people of color. The legacies of slavery also live in enlightened liberals and moderates who send their children to overwhelmingly white (private or public) schools for a, cough, “better education” while ignoring that being segregationist comes in many flavors, none of them good for their children or society regardless of what university they get into later.

Standing there the Saturday after Christmas looking at the steel bars that brace Chaney’s tombstone against destruction 56 years later, I thought of Heather Heyer, a white woman who died as an active ally to the same cause in 2017 that Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman stood and took a bullet for alongside James Chaney in 1964. I thought of George Floyd drawing his last breath at a police officer’s knee while calling for his mama in Minneapolis and also leaving a young daughter behind. I thought of a 12-year-old Black Ohio boy playing with a toy gun the way all my cousins did when I was growing up in Neshoba County, except they got to grow old, and he didn’t even as his killers were no more prosecuted than Sheriff Rainey was for shooting a young Black man well before supporting an infamous lynch mob. I thought of Eric Garner in New York City and the family he left behind I would meet later including his daughter who later died far too young, leaving her own daughter and an infant son behind.

I thought of Rita Schwerner Bender, Mickey’s wife, telling reporters from around the world outside the Neshoba County courthouse after the 40-years-late Killen verdict in 2005 that they were there because two of the men he helped murder were white. Andrew Goodman’s father said the same thing to reporters on the story back decades before.

At the foot of Chaney’s grave, I thought of how the urgency of understanding and tackling racism is continually and repeatedly shelved. I also thought of the scapegoating of my home state by Americans not wanting to face their own front yards and the roles their people might have played in it all across the U.S. It’s possible some of those same folks, the ones who believe their home’s racism pales beside Mississippi’s, whew!, placed rocks and coins on Chaney’s fortified tombstone.

Don’t mistake or either-or what I’m saying: Ignorance and denial about the full scope of racism elsewhere does not absolve Mississippi’s violent sins one iota, and I don’t resent any civil-rights pilgrimages to my state and my home county. I welcome them and have been a tour guide for such visits, including on the path both the three men and the Kluckers followed that night in 1964. I just want the pilgrims to also travel and explore the racist roads less traveled when they return home and make sure others around them know what happened across the U.S. and how it was intertwined with the horrors that occurred here, as well as legacies like overwhelmingly white schools and neighborhoods. Segregation is still segregation whether enforced by Jim Crow or not.

American’s history of racism is deep and less-known than the “Mississippi Burning” atrocities in my home county—from a long list of massacres in Black communities across the U.S. (many in 1919 alone) to the razing of a thriving Black community to build New York’s Central Park to building office buildings atop an African burial ground in downtown Manhattan (visit the remarkable memorial on the burial site now when you can). And that’s just scratching the surface.

As a Neshoba County native, I’ve had smart writers from elsewhere misquote me, indicating that I believe my county and state are the most racist places in the country. I have to then tell them not to assume words into my mouth. I did believe that before I ran from the state for 18 years in 1983, but racists out in the world believing a southern white woman would automatically agree with them proved to me that racism is epidemic throughout the nation, and beyond. That fact doesn’t minimize the odious beliefs and fascist methods of white people and the power structure here in Mississippi, once the wealth center of slavery along with Wall Street, but the facts need to exist side-by-side in our minds as we work to eliminate and overcome racism everywhere in our country. That takes deep, probing education and facing inconvenient truth, no matter where you are—from Neshoba County to San Francisco. (Yes, the “San Francisco Citizens Council” was a thing.)

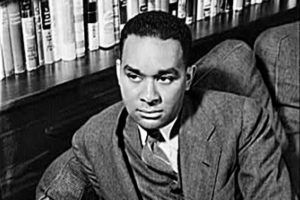

Over the years, I learned to despise the same willful and arrogant blindness elsewhere that caused Mississippi native Richard Wright big trouble back in 1945 when he called out non-southern racism, especially in Chicago, in the original second part of his autobiography, “Black Boy,” which was to be called “American Hunger.” For it to see print, Wright had to cut the part about northern racism then and did not publish that piece of his truth until the 1970s.

Face it: American racism is a shared epidemic, as is its cure. Knowledge, even if uncomfortable to face, is a vital first step all white people must take and then keep taking.

Resetting Our Nation’s Clock on Race Division

At Chaney’s cemetery, I also considered the almost-unfathomable courage it took for a 21-year-old Black man in Mississippi then to defy an entrenched white racist culture willing to kill and burn houses of worship, and of families, to hold onto their power to bend so-called democracy only in their direction. Freedom was for white people who believed like them, not for all Americans. We’ve seen this sick illogic in recent weeks as too many “leaders” in Mississippi and across the U.S. have repeatedly tried to declare Black votes null and certain majority-Black precincts in other states corrupt just because they wish it to be true. Racist arrogance means to them that evidence of wrongdoing isn’t required, just as it wasn’t in 1964 to kill those three men in the curve of a dirt road.

That inherited arrogance also means the ability to just block bothersome facts and create something called “patriotic education” as outgoing President Donald Trump and, in our state, Gov. Tate Reeves would like to do to doll up and look past transgressions we need to be learning from instead—if we are to avoid repeating them. Both Republicans and Democrats here and beyond have long whitewashed away the facts of history that can, in fact, bring us all together, regardless of partisanship, in a mission greater than either our own greed or the burning need to pretend our white ancestors, or frat brothers, weren’t part of the racist scheme. Of course, they were, or at least most of them, in one way or another, even if just through silence. Accept it and fix what they reaped for us all now, from ongoing coddling of racist university donors to the seemingly untouchable symbols of treason to uphold white supremacy that still dot our landscape with many folks of both parties, especially of a certain age, still either worship or take for granted.

Yes, here at the Mississippi Free Press, we’ve been yelled at angrily from the left for reporting on the white-supremacist truth about the men university buildings with names like Lamar and George honor.

Honestly, there is no need to desperately name everything in sight for a Confederate to help cover up white-supremacist horrors if we can just come together despite our history and differences like a Black man from Meridian and two white men from New York City did and face the truth no matter what it is. People living today did not commit the horrors of ancient ancestors; why must they guiltily act like they did then—and try to contort history to cover up vital lessons of history?

That historic truth can finally, pardon the cliché, set us free from the divisions of the past. We can work, live and perhaps even die together for something greater than ourselves, as these three young men did, leaving us a beacon to follow if we will. We can start right now to together show young Mississippians, and young Americans, a new period of history they can cherish that resets our nation’s clock on race division, while making it clear to old-school racists that it’s just not up to them any longer.

James Chaney’s activism started when he was 15 years old in a segregated school in Lauderdale County when he got involved with the local NAACP. He then went on Freedom Rides to help integrate public facilities. Later, he started working with Mickey and Rita Schwerner at the now-demolished COFO freedom school in Meridian, preparing Black people to fight for the right to vote. His life ended after the two men, and Movement newcomer Andy Goodman, drove north to check out the ruins of a church the white Christian soldiers had burned because members were organizing to vote and, thus, challenge a false worldview they hid behind.

But Chaney’s flame lives on in many of you, and in me. That he was willing to die for our state’s future has long inspired me, including to join with Kimberly Griffin to start this publication you’re reading to tell uncomfortable truths across all of Mississippi and, above all, to encourage our people to openly love, respect, cheer, support and even mourn for each other. A Black woman and a white one could not have gotten away with this kind of truth-telling together in 1964 (and certainly not with a white male reporter, openly living with his husband, who tears off sacred racist scabs and a Black woman reporter who digs some serious truth-telling on race herself). Historic realities of our state and beyond spur us on daily as we honor the Civil Rights Movement newspaper we’re named after.

A Tragedy and a Sin

When I met Chaney’s daughter Angela during a magazine photo shoot in Meridian—we shared a certain dry sense of humor and are both vegetarians—something happened that I didn’t know until later. As we waited, the great and now-deceased Neshoba Democrat Editor Stanley Dearman and I were casually discussing the possibility that the State of Mississippi might finally, thank God, bring some sort of justice by prosecuting members of the terrorist band of Klansmen who had killed her father.

When the magazine piece came out in July 2004, it had a reaction from Angela about overhearing Mr. Dearman and me say things we had said many times. “It was important to me to hear white people voicing that outrage,” she told Sheila Weller, the magazine writer, later. “I’d never known there was that much concern for justice for my father in the white community.”

Angela’s words floored me, reinforcing something I knew innately but in a way I’d never fully comprehended until I read that piece. It’s not enough to regret race violence or be “against” it or just try to lock up old Klansmen and certainly not to maintain it is all “in the past,” as I’ve been chided my entire life for talking about racism or “dredging up” the murder of Angela’s father and his brothers in the struggle. And it’s completely inadequate just to talk about racist history and violence among like-minded friends, family and colleagues. That, alas, changes nothing.

We must do the hard work—be loud and keep talking and working until this racist monster is finally beaten and sent to hell where it belongs. Silence and inaction cure nothing. It’s a lesson of 1890, 1919, 1933, 1964 and, now, 2020, and all years in between.

Plus: How dare we allow James Chaney’s daughter to grow up without a daddy and believing that no white Mississippians wanted justice for her father’s execution. That alone is a travesty and a sin.

‘I Am a Man’

A man’s tie hangs from the brace on one side of James Chaney’s tombstone. I don’t know why it’s there or who left it, but it made me think of the “I Am a Man” slogan that American and English abolitionists initially popularized. The declaration was later used to oppose the lynching and massacre fad that swept the nation in the 20th century and then in response to the Civil Rights Movement. Much like the urgent complex simplicity of “Black Lives Matter” now, “I Am a Man” talked back to centuries of degradation and terrorism of Black Americans since this nation’s reliance on slavery for growth and success began in 1619 ahead to the Dred Scott decision and then emancipation devolving into the end of Reconstruction. It was a response to decades of legal and designed and pre-publicized lynchings and massacres to terrify Black people out of organizing and exercising voting rights before, during and brutally after Reconstruction ended with the job of Black inequality undone.

The four words openly defied the American pejorative of calling Black men “boys,” four letters that said so much, none of it good.

In 1968, “I Am a Man” appeared on signs at the Memphis Sanitation Strike when 1,300 Black employees of the Memphis Department of Public Works walked out after two of their co-workers died, demanding better pay and safety measures to protect them. (Racists then and now mistakenly call this “communism.”) Martin Luther King Jr. went to Memphis during the strike and gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop Speech.” The next day, he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel there for, well, being a Black man willing to continually preach that Black lives mattered.

“In the human rights revolution, if something isn’t done and done in a hurry to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty; their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is doomed,” Dr. King said in Memphis mere hours before his death.

Decades later and amid the revival of so much overt racism nationally that I heard in Neshoba County in the 1960s, the inscription on Chaney’s grave covering speaks to a 21-year-old Mississippi man’s courage and focus on what mattered most in his time despite the sacrifices that lay just ahead for him:

There are those who are alive yet will never live.

There are those who are dead yet will live forever.

Great deeds inspire and will encourage the living.

We all owe a mountain-sized debt of gratitude to James Chaney and his civil-rights colleagues for the courage to die around the next bend in the road so that we all might together achieve the promise of American democracy. We must find the courage and grit to keep fighting until the dream is fulfilled and that beloved arc of the moral universe is finally bending entirely toward freedom and justice for all.

Put simply: We must stop moving backward toward 1964 where a young Black man from Meridian and friends died for the greater good. We can do this for them, and for us.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to donna@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.