As Black History Month unfolds this week, I’m thinking a lot about Mississippi and U.S. history of race and racism, specifically white supremacy, and what it has done to our state and nation.

Let’s be honest: I think about this a lot year-round, and I regularly publish journalism and essays with this history embedded and contextualized to help me, and hopefully us all, understand the ongoing and devastating effects of those realities on today’s Mississippi and America as a whole. The goal, always, is to inspire people across divides to embrace solutions together. The only way to get there is by facing the past and its effects.

Plus, we have a lot of lost opportunity to make up for, considering how much of our history was simply censored out of our textbooks and why (to protect white supremacy). And as we can see from all the 1776 Commission and “patriotic education” mumbo-jumbo, some people holding the reins of power clearly think that a state and nation finally learning our whole history, racist warts and all, might use what we learn to change some things. And they’re right about that. Learning real, unexpurgated history would bring needed change and more actual “reconciliation” because we’re all learning from the same history books.

Talk about being in it together.

Of course, this kind of context is a key part of what makes our journalism different and why Kimberly Griffin and I started this publication nearly 11 months ago in March 2020. We and an amazing, dedicated, growing team have spent the last 10 months since we launched doing this kind of embedded-history reporting statewide in the Mississippi Free Press, including turning over historic and recent stones many would rather remain untouched. Now it’s even more urgent in the wake of the Jan. 6 white-supremacist insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Every American, regardless of race or ethnicity, needs to understand all of history, what it’s done, what it teaches, what it means, what it can predict and what it can prevent.

That’s exactly why some extremists want painful, horrific events whitewashed from our history books rather than understanding that we can all handle it together; in fact, that’s the only way we can. Real history, known and understood, shifts power to a far more politically and ideologically diverse collaboration of Mississippians and Americans who aren’t driven by partisan whims and the political horse race of the day. We can have intelligent debates and make better, transformative decisions for ourselves and our communities. We can grow, and we can thrive as a state without constant bickering and finger-pointing over trivia. Imagine.

White Supremacy Has Never Been Partisan

Such Lost Cause-style censorship is so tragic for so many reasons. First, white supremacy in America has never been a partisan issue; it’s always been about fomenting hate and distrust of others to limit access to power, the ballot and resources. History teaches that racism is on the left, the right and in between—if that’s even how you frame politics in America. Personally, I try to avoid limiting left-right paradigms and know that blind partisanship limits all of our potential. We need to think bigger than two-sided political debates.

Second, blanking out the difficult parts of our history erases so much resilience, collaboration and, yes, even joy of coming together to fight for something bigger than ourselves: love over hate; equity over discrimination; inclusion over othering; understanding over ignorance. And, yes, democracy over any sort of fascism or totalitarianism such as the kind scratching on our front door of late.

I thought of all this, smiling throughout, as I read culture reporter Aliyah Veal’s piece about the unstoppable Flonzie Brown-Wright’s spending 11 months out of each year to organize the historic New Hope Baptist Church’s annual Black History Month program. She designed it to teach the history that is purposefully omitted from our history books and lift up Black heroes we all should know, far from New Hope’s pews. This is American history, filled with bravery and heroes and a lot of joy, and we all should learn it.

On the Other Side of the Hate and Division

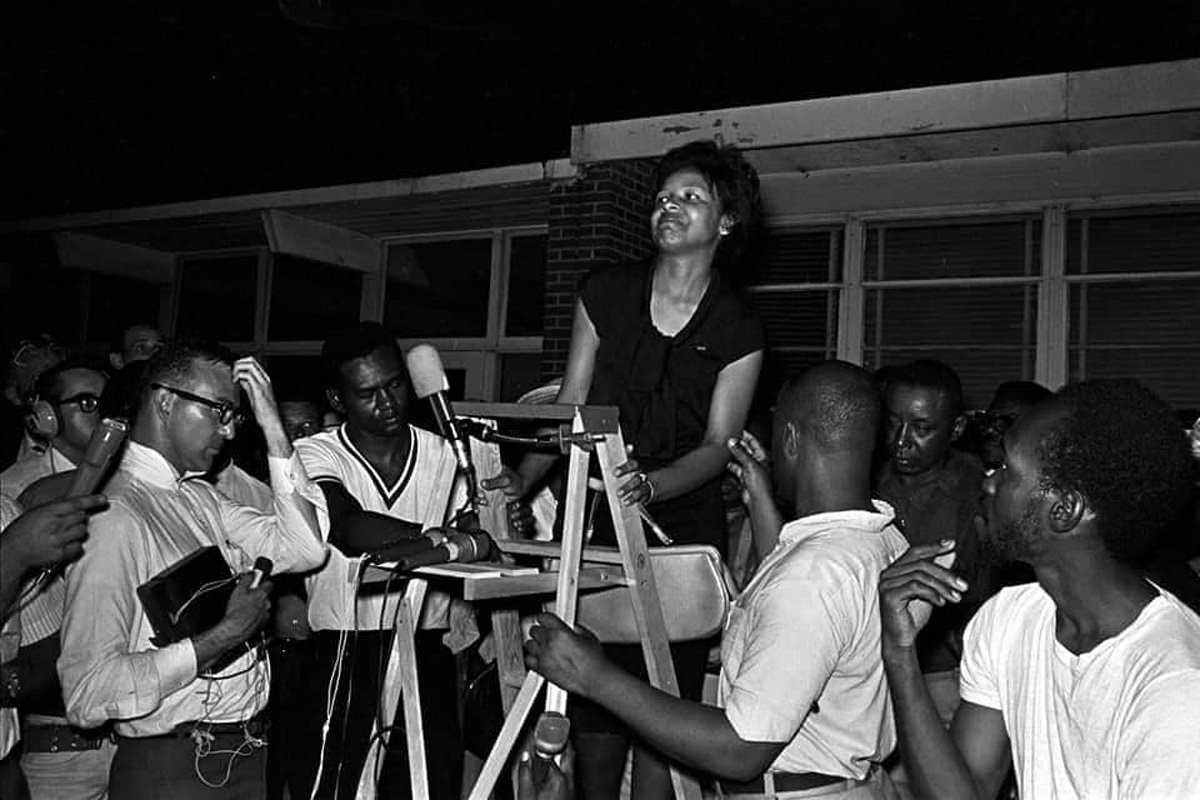

I smiled while editing the piece about New Hope because I know this über-organizer and because Flonzie makes me laugh and feel the joy of a woman who loves life to pieces. She has spent most of her time in this world, yes, speaking truth to power; climbing on ladders to organize protests and dissent; being mentored by the likes of John Lewis during the Movement; and even getting a prominent lake and park in Jackson integrated back in the 1960s so her son could play there.

If it needs to be done, Flonzie Brown-Wright gets to work. She works with a wide variety of people; she and I both attend the retirement luncheon for an outgoing FBI leader, for instance. I doubt she has spent five minutes of her life wondering if her efforts will be for naught or asking permission to speak out and speak up.

She is what a hero and a leader looks like.

Flonzie Brown-Wright inspires me, as do so many Mississippians of all backgrounds who have kept this state moving forward after being pretty much the bottom when it came to racism and race violence and all the resulting impacts. So many of them faced threats, violence, disparagement with courage and determination to basically save us all from staying immersed in a dark history of division and hate.

In a conversation last week, a white friend who believes in racial justice told me that he just doesn’t think Mississippi will ever really let go of its racism: too many have dug into the lies for too long. They’ll never change, he posited.

We all have those moments of despair—but ultimately I don’t believe that, my hero Flonzie doesn’t believe that, and most of you don’t believe that, either. We don’t accept Mississippi’s defeat because we know people who have learned true history and who have changed as a result. I’ve personally met hundreds (at least) here in the last 20 years who have discovered the joy on the other side of the hate and division. Many walk up to me in the grocery store and confess, in fact. It’s a perk of doing what I do so loudly and proudly. People like to tell me stuff.

I believe to my core that much brighter days are ahead for Mississippi—but only if we all stay in the fight with passion, mutual respect, tenacity, love and, yes, joy. As this Black History Month dawns, and every single month, we must join our voices to discuss and learn from our shared history and, yes, sing a bit together while we’re at it. Or, if you’re like me, listen to others who can actually sing.

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an essay for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and factcheck information to azia@mississippifreepress.com. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.