JACKSON, Miss.—Stephany Brown used to have a wide variety of grocery-store options to choose from in south Jackson but not any longer. The Kroger on Terry Road down the street from her house closed its doors in 2015, and even the Walgreens on that same street recently closed down, though the neighborhood still has a few Dollar Generals and Family Dollar stores. The only option the community has for groceries is Food Depot, but it’s not enough for her.

“Food Depot doesn’t always have the freshest vegetables. The vegetables are kind of old and wilted looking,” Brown said. For higher-quality produce, she visits stores farther away.

She and her husband, Herbert Brown, live in one of the capital city’s food deserts, meaning they have to travel miles outside their community to get quality groceries.

They shop at the Kroger in Pearl, over in Rankin County, which she said is closer than going to the locations in Byram or Clinton. As far as grocery shopping is concerned, the pandemic hasn’t really changed anything for them, she said.

While they rely on Kroger for fresh vegetables and fruit, the Browns visit Food Depot for fire logs, her favorite creamer for coffee or for smoked turkey necks to put in her greens, she said. But another reason the couple opts to shop elsewhere is they believe groceries cost more in their neighborhood.

The Jackson Free Press reached out to Food Depot for comment about its south Jackson store, but could not reach a representative.

Stephany Brown said her husband will leave an item on the shelf that he believes he can get less expensively at Kroger, which they leave Jackson to visit. The Pearl store is closer with the only Kroger left in the 81%-black capital city 10 miles away in north Jackson. In an area with little grocer competition, Food Depot remains crowded.

The couple is retired and has adequate transportation, so they can go to other grocery stores; however, many in the community—where poverty is rife and transportation often limited—do not have the luxury to leave their community for better groceries.

“(It’s) probably because it’s an African American-based community or the poor people, and that’s what these stores do because they know that’s where you have to go, so you pay the higher prices,” Stephany Brown said.

The University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities reports that food deserts are places where urban residents live more than a mile from a grocery store that sells fresh produce and meat, and rural dwellers must travel more than 10 miles. The only options for food items in such food-insecure areas are often high-priced convenience stores and gas stations largely selling junk food.

Food deserts are in poorer areas with 20% of residents living below the poverty line, and food-insecure areas are often heavily populated with people of color who cannot afford reliable automobiles and where transportation hours and access is limited, such as in Jackson.

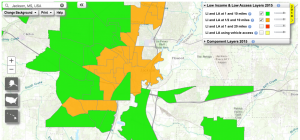

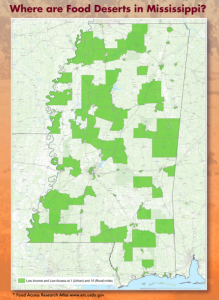

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture mapped food deserts across the U.S., showing that large swaths of Jackson that have steadily become blacker and browner due to white and economic flight, are food deserts under the accepted definition.

Stephany and her husband are in their 60s, a vulnerable population more susceptible to catching COVID-19. They wear their masks and gloves when they go out, she said, and while there are options to pick up groceries or get them delivered, she doesn’t want anything delivered in a box.

“I want to be there and pick up my own stuff,” she said. “For people that are in my age group, and I can only speak for myself, we’d rather just go and get our own food because that’s what we’ve done all our lives. Just put on a mask and wear gloves and go during our time when you’re supposed to go. Don’t go out there and goof off.”

‘It’s Still Taking a While to Catch Up’

GlobalData managing director and retail analyst Neil Saunders said drugstores and grocery stores are doing well in the market during COVID-19 with sales rising, despite enormous pressure on suppliers to get products and groceries out in a timely fashion.

“A lot of suppliers have increased production and increased capacity, but it’s still taking awhile to catch up and for everyone to adjust to the new reality,” Saunders said.

The hardest-hit items are paper towels and toilet tissue because their bulky packaging takes up a lot of space on trucks, and as soon as they hit the shelves, they’re gone in a matter of hours, Saunders said. But fresh fruits and vegetables, in general, are more available, he said.

“Produce is an area that hasn’t been as badly affected in terms of demand, and so most grocers have been able to keep the produce section very well maintained, and the quality is still very high,” he said.

Saunders said he has not seen evidence of much price-gouging by mainstream retailers, but independent or online retailers could be spiking prices. But they shouldn’t, he added.

“That has gone down very badly with consumers. They don’t like that. They see it as being unfair, and some people buy at that price if they’re desperate to get hold of things,” he said.

In a statement after the COVID-19 crisis broke out in Mississippi, Attorney General Lynn Fitch said her office has been receiving phone calls from people across the state about possible price-gouging on essential items like water, hand sanitizer and toilet paper.

“My office will not tolerate price gouging or any scams that take advantage of these circumstances. We have been sending cease-and-desist letters to offenders brought to our attention and will continue to do so and take any other appropriate actions to protect the people of Mississippi,” Fitch said in a statement.

But people living in food deserts with little or no choices for quality food are at particular risk during the pandemic, Saunders said. Before, quality food choices were low, but the shelves were still stocked. Now, shelves may be depleted, and the option for another store might not be available, he said.

“People who live in areas where there is lots of choice, that’s fine for them. If you live in a food desert, and you don’t have access, and the store that you use doesn’t have stock of these things or (sells) them at a higher price, you have very little choice,” he said.

“Many of these communities are poorer, and these are the folks that have been affected by unemployment and perhaps don’t have the savings to see them through. It’s a double hit for them.”

This is even more true in areas such as the Mississippi Delta with severe wealth disparities among its large black population that date back to slavery and sharecropper eras. Mississippi State University sociologist Troy C. Blanchard’s study, “Retail Concentration, Food Deserts, and Food Disadvantaged Communities in Rural America,” found that Mississippi areas with historic “hardship and deprivation”—specifically the former cotton-production centers of the Delta and Black Belt counties of Chickasaw, Clay, Lowndes, Monroe, Noxubee and Oktibbeha—are “severe” food deserts, he and Thomas A. Lyson of Cornell University wrote.

Blanchard cited U.S. Department of Agriculture findings that rural Lower Mississippi Delta counties average one supermarket per 190.5 square miles, with more than 70% of low-income Delta residents forced to travel at least 30 miles to buy groceries beyond what they could find in convenience stores or gas stations.

‘It’s Just Getting Worse’

APM Research Lab reports that, as of May 12, 2020, the COVID-19 mortality rate for African Americans is 2.3 times higher than that of Asians, 2.2 times higher than Latinos and 2.6 times higher than white Americans.

Sarah Davenport, a PhD student in anthropology at Brown University, said these high rates are due to discrimination in the medical system, as well as the slow violence that food insecurity was already committing against their bodies and their health before the COVID-19 crisis.

“People are saying, ‘Well, it’s people who had diabetes already and people who had heart disease already.’ It’s not like that’s normal,” she told the Mississippi Free Press. “People are dying because they had nutrition-related illnesses because they already had food insecurity before, so they had a higher risk of getting ill and dying.”

But food insecurity is working in myriad other ways during this pandemic, Davenport said. At Brown University, she and other students hosted talks that offered food to students and non-students. But with schools closed, people cannot get these meals or the food banks the school supports, Davenport said.

“If you think about all the other places where food banks rely on businesses or restaurants to supply them with leftovers, and that’s not happening, now the food banks are struggling to get what they need,” she said.

Internationally, countries like Jamaica, Cuba and Venezuela are struggling on the food-insecurity front, as landworkers, who produce the food, are struggling to get access to food themselves, Davenport said.

“A lot of Caribbean countries rely on tourism and importing food for tourism, and now they can’t import what they need, and they don’t have tourism, so they can’t participate in a global economy,” she said.

“There’s all of these things happening at once. It’s crazy, and it’s just getting worse.”

Davenport said creating alliances is a great solution to help combat food insecurity.

“If anything, donate to your local food bank. When classes are over, I’m out of here, and I’m going home, and I’m going to do something in my community. What’s important is that I save up my resources right now, and I do something,” she said.

Growing food at home, donating canned goods out of your cabinet, getting groceries for those who don’t have the means to get out, and connecting with other organizations to see what they’re doing are other ways Davenport suggested people can help fight food insecurity right now.

“I’m taking responsibility for the resources that I have available, and solidarity is giving what I have and not what I think I need,” she said. “Not hoarding, but sharing the things I can share, whether that’s money, time (or) food. We need to create a network like that between each other.”

‘Not Your Typical Hoarders’

Main Street Market in rural Utica, a 75% black community 40 miles southwest of Jackson, has been open since September 2019, serving a community of around 850 to 900 people, owner Destenee Green said. It’s a town so small they don’t even have a stoplight and, much like south Jackson, in recent years it has been a food desert. That can be even more challenging in rural areas, which are considered food-insecure if residents have to travel more than 10 miles for a grocery store with fresh produce and meat.

“We used to have a grocery store when I was younger called Sunflower, but Sunflower closed down. That was around 2015, 2016,” Green, who is a friend of this reporter, told the Mississippi Free Press.

Without access to an adequate grocery store, her mother and other residents would have to travel 35 to 45 minutes outside Utica to get fresh produce and meat. Her mom, Ella Green, would shop at grocery stores in Clinton and Jackson.

Destenee Green, a scientist for L’Oreal who lives in New Jersey, and Alliot Green, information technology division manager for Pial who lives in New Orleans, realized not everyone in Utica had this ability. So she and her brother came together with her their cousin, Shanique Davis, who was renting the building that is now the store, and they started brainstorming.

“(We) were thinking, ‘How can we give back to the community? How can we make sure our mom is taken care of? How can we make sure our legacy is intact?’ So that’s how Main Street Market came to be,” she said.

The store takes its name after the street it resides on and sits in the epicenter of Utica, next to the town’s bank and furniture store. Green said most small businesses don’t make it in the first year, so the pressure is on. But the store has been holding up well during the pandemic, she said.

“It’s helped us because people obviously need access to foods and stuff like that. But when you look at how rural Utica is, like we’re already, in a way, spaced out. So these people that are coming in to buy groceries, they’re not your typical hoarders like the people that were panic-buying at the beginning,” the co-owner said.

Ella Green, Destenee’s mom, is managing the store and has a handle on keeping supplies stocked, from cleaning supplies to thermometers, the daughter said. All their employees wear gloves and masks, and her mom mops and cleans the store every night after closing.

“We don’t have any tape on the floor as far as social distancing, but our traffic is not like the traffic you would see at a Target or a Walmart. The most we’ve probably had in the store is probably 10 people at one time. We won’t see 50 people trying to come into the store at one time,” she said.

‘Going Home to Grocery Shop’

Unlike most corporate-owned grocery stores like Walmart and Kroger, Main Street Market hasn’t had to put a limit on any products. The store stocks plenty of Lysol, thermometers, tissue and water, and they even have people coming into the community to get what they need, she said.

“Some dude posted something on Facebook like, ‘I work at CVS, and we sold out of thermometers days ago. Now how these people in Utica have thermometers I have no idea, but I just bought 10 of them to give to my family,’” she said. “We’ve been seeing people come in and refer to it as going home to grocery shop.” The dude turned out to be her cousin, but she didn’t know that’s who it was at the time.

Retail Analyst Neil Saunders said small, independent grocery stores are doing just as well as the big grocers.

“They sell the types of products people are currently stocking up on, which is the main reason for their success. However, the fact that they are local means people don’t need to travel as far as they would to a big supermarket, which is a plus right now,” Saunders said. “There is also something to be said about the sense of community people have towards smaller, local grocers.”

He said these small grocers will not see the same rise in sales that the corporate supermarkets do, but growth will certainly occur.

“They may be able to deliver that growth more profitably, too, as they don’t have complex supply chains or staffing requirements like the bigger players,” he said.

Green said sales for the store fluctuate with high traffic on the weekends and steady traffic on the weekdays, and they haven’t had any issues with their suppliers. But she expressed that things could be very different if their store happened to service a city like Jackson or Clinton.

“I think the supply demand would be completely skewed,” she said.

Green said it’s important for them to let the community know that the store is practicing social distancing, that it is cleaning and that they are taking the necessary precautions. “Just making sure the community knows, verbally letting people know that, and physically what that looks like in the store,” she said.

This is the first part in culture reporter Aliyah Veal’s occasional solutions-driven food insecurity series in Mississippi. Send her story tips about the state’s food deserts and solutions needed or underway to aliyah@mississippifreepress.com. See a UMMC collection of food-desert research and papers here.

Editor’s note: The original version of this story included a photo of a now-closed Utica grocer that the caption identified as the Main Street Market. The photographer is returning to Utica for a photo of the Main Street Market, which we will add to the above story as soon as possible. We apologize for the mix-up.