News of Elwood Higginbottom’s death reached the Lafayette County Courthouse before the jury had finished deliberating his case, cutting the Sept. 17, 1935, trial short.

Just a few hours earlier, rumors had circulated that the white jury would find Higginbottom not guilty after Judge Taylor McElroy instructed the jury to consider whether the Black man was justified in killing Glen Roberts, a white man. Higginbottom had pleaded self-defense.

“The court charges that if you believe from the evidence in this case that the deceased went to the home of the defendant on the night of the homicide and entered the home of the defendant in a rude, an angry manner, and then and there held a pistol pointing toward the defendant then and there had reasonable grounds to believe and did believe his life to be in immediate danger at the hands of the deceased, then defendant had the right to shoot and kill the deceased in his necessary self-defense, that the jury should find him not guilty,” the jury instructions read.

After getting into a disagreement over land with Higginbottom, news reports said Roberts came to the sharecropper’s home armed with a pistol, with 25 other men in tow. Despite this crowd, the judge allowed only three witnesses at the trial: Higginbottom, his wife and the county sheriff.

A mob of 50 white men gathered outside the jail, at an address that would now be inside the Lafayette County Chancery Courthouse. The mob made their way into the jail, reportedly overpowering the sheriff and then abducting Higginbottom.

They hanged, shot and left Higginbottom to die dangling from a tree off the corner of what is today Molly Barr Road and North Lamar Boulevard, castrating him before leaving. Elwood, also a labor organizer, was not yet 29 years old when he died.

Jimmy Faulkner, just 8 years old was part of the crowd watching the lynching, recounted the story to his uncle, William Faulkner. Higginbottom became the basis for William Faulkner’s character Lucas Beauchamp in “Intruder in the Dust” and Rider in “Pantaloon in Black,” literary scholar John F. Kinney told Burke for her research.

After Higginbottom’s murder, his wife and children fled Lafayette County. Locals beat and threatened his siblings with lynching, forcing them to flee as well.

Prioritizing safety, branches of the Higginbottom family lost touch with each other as they escaped. As time went on, the Higginbottoms didn’t talk about their patriarch’s lynching, leaving much of the family in the dark for decades.

Despite the fact that more than 150 men, women and children watched the mob lynch Higginbottom, no one was ever arrested for the murder in Lafayette County, continuing the fearful effects of white terror on the county’s 8,236 Black residents, then 41.2% and today 23.25% of the county’s population.

Valerie Reaves, the Higginbottom family historian who lives in the Atlanta area, mourns not only the loss of Elwood, but an entire branch of her family, she said on April 2, 2022, in her speech at the dedication of a long-overdue lynching memorial in the county that ranks in the top five Mississippi counties for the most lynchings.

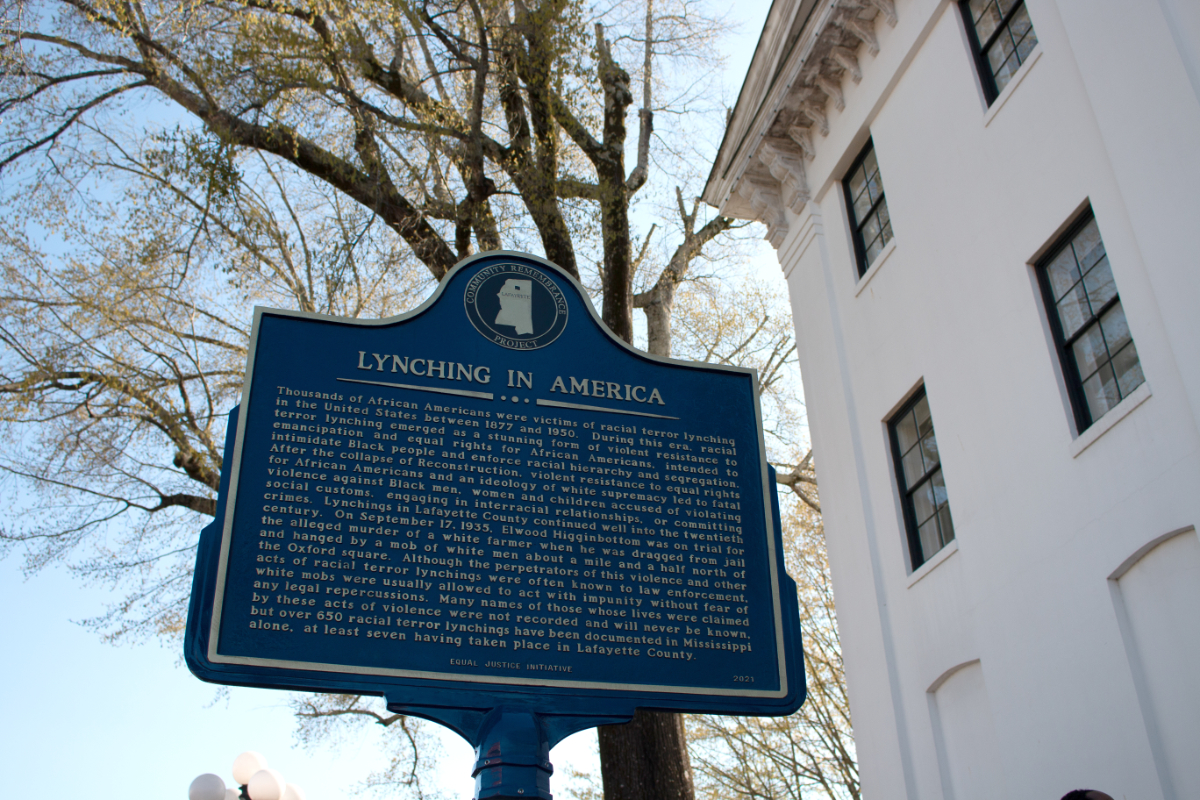

After several years of pandemic-induced delays, Lafayette County was finally able to hold the opening ceremony for its lynching victim memorial, which passed through levels of local bureacracy, pushback and even historically challenged complaints that a man lynched before a trial had hurt a white woman.

The memorial, a new plaque on the courthouse lawn—on the side, just a few meters away from the Confederate statue that sits on a pedestal in front of the lawn—is dedicated to seven lynching victims. A mixture of locals and family members opened another memorial, a bench dedicated to Higginbottom, on the same day at Oxford’s Old Armory Pavillion.

Searching for a Lost Family Member

In 2018 Tyrone Higginbottom, a Memphis resident searching for his family history, joined Ancestry.com and submitted his DNA for analysis. At the same time, Northeastern University Law School student Kyleen Burke was looking for the Higginbottom family, the Commercial Appeal reported.

Burke and her peers had an assignment to research and track the cases of two lynching victims each, a part of their work at the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Clinic. Higginbottom was Burke’s case.

In 2017, Burke traveled to Oxford, presenting her pre-published findings and dropping off a packet of information to the Higginbottom family, bringing the first beams of light to family history.

Even today, more Higginbottom history is emerging, April Grayson said in her speech at the bench dedication. Grayson was one of the lead organizers of the lynching memorialization, working with the Lafayette Community Remembrance Project and for the Alluvial Collective, formerly the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation.

A woman in her 90s living in Maryland had seen a news article about the memorial dedication and recognized Elwood’s name, Grayson said.

The woman called Grayson, telling her story of growing up in her father’s store in Oxford, where Elwood would bring frogs to the then-young girl. She remembered him fondly, and invited her friend’s family to reach out to her son for more information, as she is not able to speak clearly over the phone.

Rico Washington led the exit prayer. He was one of the many Higginbottom relatives who returned to Oxford for the memorialization of Elwood Higginbottom’s lynching, reunited with his family as a result of the effort.

Grayson will always be a sister to Reaves for reuniting the branches of the Higginbottom family, the family historian told the Mississippi Free Press.

‘Swingin’ in the Southern Breeze’

Donald Cole gave the opening remarks for the memorial’s dedication ceremony. In 1970, Cole was one of eight students suspended from the University of Mississippi and 89 students arrested for participation in a non-violent civil-rights protest on campus. Cole later served as an administrator at the university until his retirement in 2018 and, in 2020, the university decided to rename its Student Services Center in his honor.

Soon, Oxford local and civil-rights activist Effie Burt performed “Strange Fruit,” Billie Holiday’s haunting song about lynching. The lyrics come from Abel Meeropol’s poem published in 1937.

“Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root /Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees,” the poem began. “Pastoral scene of the gallant South / The bulgin’ eyes and the twisted mouth / Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh / Then the sudden smell of burnin’ flesh / Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck / For the rain to gather / For the wind to suck / For the sun to rot / For the tree to drop /

Here is a strange and bitter crop.”

Cole stood quietly, listening to Burt perform.

“I am beyond grateful to live at a point in time when I will never see that strange fruit hanging with my own eyes,” Cole said, the Daily Mississippian reported.

The bench dedication, just a few miles away, began shortly after the memorial service came to a close. Rev. Gail Stratton opened the bench dedication with a prayer before Grayson and the Higginbottom family spoke.

Roadblocks to Building Oxford’s Lynching Memorial

Soon after learning of Burke’s research the organization now known as the Alluvial Collective set to work in 2017, alongside the fledgeling Lafayette Community Remembrance Project, on establishing a memorial marker for the lynching of Elwood Higginbottom. Led by Grayson, they found the exact location of Higginbottom’s lynching, and reached out to the Higginbottom family to invite them to be involved in the effort.

Coordinating with the Equal Justice Initiative and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., they were able to erect the marker on the corner of North Lamar Boulevard and Molly Barr Road, the site of Elwood’s lynching, in 2018.

After some convincing from his daughters, Elwood’s son Rev. E.W. Higginbottom Sr. returned to Oxford. E.W. had not returned to the area since his family fled following his father’s murder, The Clarion-Ledger reported; he was just 4 years old when his family was forced to flee.

E.W. and his family visited the site of the lynching with the Alluvial Collective, Grayson recounted for the Mississippi Free Press in 2020. The site was a tree off of the corner of Molly Barr Road and North Lamar Boulevard, one of many public streets and buildings bearing the name of L.Q.C. Lamar.

L.Q.C. Lamar was a Confederate politician and large slaveholder on his Solitude plantation in Lafayette County who helped draft Mississippi’s Ordinance of Secession as the Civil War began. . He was also an open white supremacist declaring in speeches to Confederate veterans that Black people were inferior even as he worked to end Reconstruction and reverse laws to allow freedmen access to public education, the ballot box and equal rights. He believed in “the supremacy of the unconquered and unconquerable Saxon race,” as Lamar proclaimed in a speech in Aberdeen, Miss.

At the area around Higginbottom’s lynching site in 2020, the family took turns filling two jars with dirt: one to be sent to the Equal Justice Initiative’s Community Remembrance Project collection at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery in Montgomery, Ala., and one seen at the dedication of the county lynching memorial four years later.

In September 2019 Grayson’s group proposed the memorial to the Lafayette County Board of Supervisors, which voted 4-to-1 to approve placement of the marker on the courthouse lawn. District 4 Supervisor Chad McClarty, the only disapproving vote, had an issue with the description of the lynching of William Steen, who was murdered in 1893 after an alleged affair with a white woman, the Daily Mississippian reported following the 2019 vote.

McClarty and the board agreed to have the Mississippi Department of Archives and History approve the language on the marker, WREG reported.

After MDAH approved the wording of the marker, the memorial’s approval faced another delay in December 2020 when Lafayette County District 3 Supervisor David Rikard brought up opposition to Lawson Patton’s name being included in the memorial’s list of victims, Christian Middleton reported then for the Mississippi Free Press.

The white lynch mob murdered Lawson Patton, sometimes called Nelse Patton, who was accused of killing a white woman, before the courts could decide his case as was routine in extradicial lynchings. Ex-U.S. Sen. W.V. Sullivan of Mississippi led the mob that murdered Patton, a Sept. 8 1908, New York Times article shows.

“I led the mob which lynched Nelse Patton, and I’m proud of it,” Sen. Sullivan said publicly then. “I directed every movement of the mob, and I did everything I could to see that he was lynched.”

In the end, Lafayette County Community Remembrance was able to get all seven of the proposed names onto the memorial plaque on the Lafayette County Courthouse lawn. Two of the lynching victims, William McGregory and Lawson Patton, were murdered on the same courthouse lawn, and one lynching victim listed on the memorial remains unidentified.

‘Racial Hate Isn’t An Old Problem’

Despite the tendency to place lynchings in the past, a Georgia jury convicted Ahmaud Aubrey’s killers for his racially motivated murder just a few months ago.

In January, 24-year-old FedEx driver D’Monterrio Gibson was working in Brookhaven, Miss., when, he would allege later, two local men chased and fired at him while he was delivering on his route. Social worker Reginald Virgil attended a press conference at the Cochran Law Firm in Ridgeland to support Gibson, and spoke to Mississippi Free Press reporter Kayode Crown.

“D’Monterrio is still here to tell his story of what happened, to share the traumatizing event that he went through,” Virgil told Crown. “And typically for Black people, that’s uncommon in our country, but God has blessed him to be here with us, and all of the support that is here for D’Monterrio is going to support for justice to make sure these men are put behind bars for trying to kill him.”

Lynching was not classified as a hate crime on the federal level until March 29, 2022, less than a month ago, when President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act into law. More than 200 attempts at passing anti-lynching legislation at the federal level had failed since 1990, as well as anti-lynching resolutions that Mississippi’s white U.S. senators have consistently opposed through the decades.

“To the Till family, I remain in awe of your courage to find purpose through your pain,” President Joe Biden said while signing the law. “… But the law is not just about the past. It’s about the present and our future as well, from the bullets in the back of Ahmaud Arbery to countless other acts of violence, countless victims known and unknown, and the same racial hatred that brought that mob carrying torches out of the fields of Charlottesville just a few years ago.”

“Racial hate isn’t an old problem,” Biden said. “It’s a persistent problem.”

Last month, Action News 5 reported that Elwood’s granddaughters celebrated the passage of the anti-lynching law as well.

“I wish this would have been done back then because we didn’t get a chance to meet our grandfather because that’s something any kid would want,” said Delois Wright, one of Higginbottom’s granddaughters, to Action News 5 in their March 29, 2022 piece.