A monument dedicated to the seven known lynching victims in Lafayette County will go up on the lawn of the county courthouse in Oxford. But it will include language stipulating that one of the men lynched was accused of “murdering” a white woman although he was never convicted of the alleged crime.

The Mississippi Free Press reported earlier that a member of the all-white and male Lafayette County Board of Supervisors was insisting on language specifying the alleged crime of Lawson “Nelse” Patton, one of the seven Black men known to have been murdered and lynched in Lafayette County, before he would vote to approve the marker. A white mob, led by former U.S. Sen. William V. Sullivan, abducted Patton from the Lafayette County jail in 1908 and hung him from a telegraph pole on the court square. He was accused of murdering a local white woman he had delivered a message to while working as a “trusty” at the jail.

“I led the mob which lynched Nelse Patton, and I’m proud of it,” Sullivan said publicly then. “I directed every movement of the mob, and I did everything I could to see that he was lynched.”

After more than a year of deliberating, the Lafayette County Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the lynching marker on Jan. 19, 2021, after members of the Lafayette Community Remembrance Project, the multiracial group responsible for the project, agreed to add the language about Patton in order to move the marker forward.

District 3 Supervisor David Rikard raised the issue with proposed language for the marker, which stated earlier that Patton was “accused of the death of a white woman.”

At the behest of the county supervisors, members of the memorialization group changed the marker’s language, which will now state that Patton was “accused of the murder of a white woman” (emphasis added).

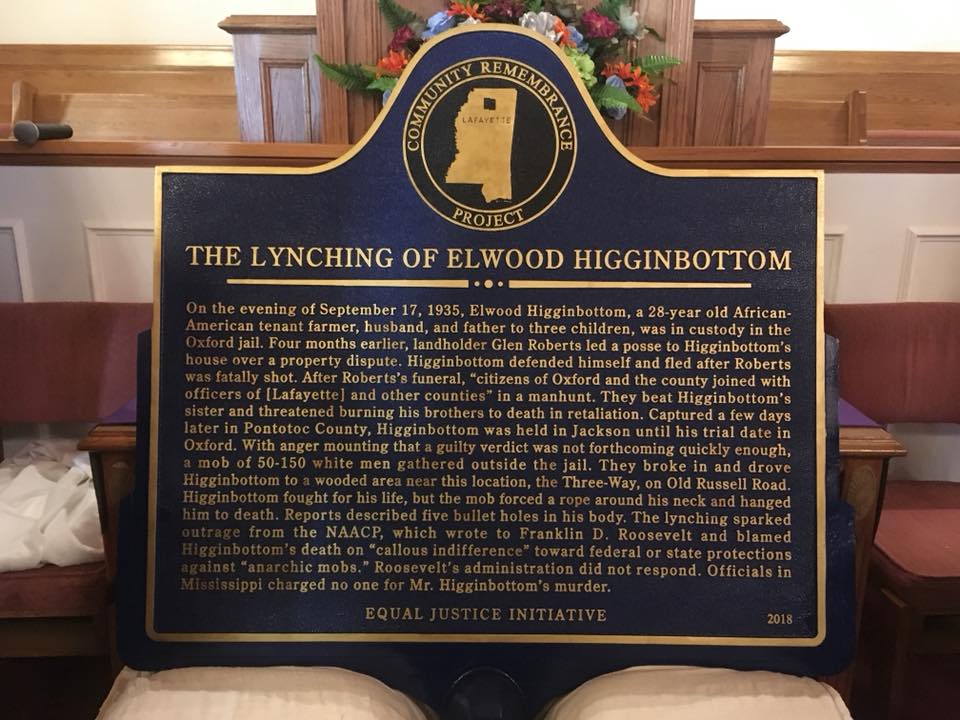

Other known lynching victims murdered in Lafayette County are: Harris Tunstal (1885), Will McGregory (1890), Name unconfirmed (1891), William Steen (1893), William Chandler (1895) and Elwood Higginbottom (1935).

‘To Make White People Comfortable’

On Dec. 7, 2020, Supervisor Rikard told members of the steering committee of the Lafayette Community Remembrance Project that he did not want Lawson Patton’s name on the marker at all, claiming he could not agree to memorializing someone who committed what he referred to as “unspeakable acts.” It did not matter to him that Patton was never tried or convicted of murder, or that white Mississippians often falsely accused and punished Black people for crimes they did not commit, often with mob violence.

After subsequent public and backroom meetings with members of the memorialization steering committee, the supervisors were finally convinced that Patton could be included on the marker so long as the language describing him was altered to emphasize that he murdered a white woman, which was never proved.

Dr. Darren Grem, a University of Mississippi professor and historian, has studied what is known about Lawson Patton’s life, as well as the tendency to use violence or threats against white women as an excuse for violence and murder of Black men.

“I don’t necessarily know what’s going on in their heads and their perspective,” Grem said of the Lafayette supervisors, “but from a historian’s point of view, it’s somewhat problematic to pull one figure out and in some ways kind of demand moral perfection from a victim, or bringing up their alleged—and it’s very important to say this—alleged crimes from over a hundred years ago as a kind of justification for leaving them out of public memory.”

White Vengeance: ‘Difficult, If Not Impossible to Control’

That excuse for extrajudicial vigilante justice against Black people in America was deeply embedded into the white American, and especially southern, psyche well into the 20th century. Nine years after the Oxford mob hanged Patton, Georgia Gov. Hugh Dorsey wrote a letter to the Colored Welfare League of Augusta, Ga., who had protested the recent lynchings of four Black men in south Georgia and the white lynch mob’s “disregard of the courts and the law.”

In the letter, Dorsey used blame-shifting logic that sounds eerily similar to many responses to police brutality and shootings of unarmed Black people today. “The surest way to discourage lynchings is to convince the lawless element that such provocative outrages will not be tolerated, palliated or shielded by good citizens of any race,” Georgia’s top official wrote, meaning that Black people should not complain about the lynchings if they could not stop the alleged crimes that inspired the lynchings. The letter, quoted generously on the front page of the Natchez Democrat in Mississippi on May 24, 1918, chastised Black people opposed to lynching for not issuing the same kind of resolutions with outrage against the crimes that got African Americans lynched, which was to be expected, Dorsey reasoned.

The Georgia governor wrote that violence “against helpless women and children will not be tolerated by any civilized community, but will provoke prompt retaliation of community vengeance which is difficult, if not impossible to control….”

The same excuses for violence did not, of course, apply to Black people who might seek vengeance for the epidemic of white violence against them, which was seldom punished. Prior to becoming governor, Dorsey had prosecuted Leo Frank, a gay Jewish man, for the murder of a 13-year-old girl. After Frank was convicted in 1913, in what has long been considered a travesty of justice, a lynch mob took him from jail and hanged him from a tree in Marietta, Ga.—a rare instance of a lynching victim who was not Black.

As happened in lynching after lynching—with no reliable way today to know whether the accusation was true or an excuse for violence—Nelse Patton’s Oxford murderers justified abducting and killing him because of his alleged violence against a white woman. This accusation aligns with what famed investigative reporter and NAACP co-founder Ida. B Wells called “the old threadbare lie” that long undergirded the violence of white supremacy: Myths of Black violence and sexual crimes against white women were used to vindicate mob violence to, in one way or the other, keep African Americans in their perceived place.

“Nobody in this section of the country believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men rape white women,” Wells wrote in her 1892 editorial in the Memphis Free Speech. “If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves, and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

Ida B. Wells: Lynching Used to Squelch Black Vote, Power

Ida Bell Wells was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Miss., in 1862. After the defeat of the Confederacy led to her freedom, she became an activist and a journalist in Memphis. Her central concern was the growing scourge of lynching and race massacres that white supremacists embraced through Reconstruction and beyond. Known today as the “most prominent anti-lynching campaigner” in U.S. history, Wells took on directly the prevailing excuse that Black men deserved to be lynched for accusations of hurting white women, regardless of what the real reason might be.

“The lynching record for a quarter of a century merits the thoughtful study of the American people. It presents three salient facts: First, lynching is color-line murder. Second, crimes against women is the excuse, not the cause. Third, it is a national crime and requires a national remedy,” Wells told the National Negro Conference in 1909, the year after Patton’s lynch mob hid behind the “murdered a white woman” excuse to first shoot and then hang him.

The real reason for lynchings, Wells taught through her data-heavy journalism, was the need to hold onto white power. “This was wholly political, its purpose being to suppress the colored vote by intimidation and murder,” Wells said in 1909 of the wave of white-mob violence that swept the South and beyond into the 20th century. “Thousands of assassins banded together under the name of Ku Klux Klans, ‘Midnight Raiders,’ ‘Knights of the Golden Circle,’ et cetera, et cetera, spread a reign of terror, by beating, shooting and killing colored people by the thousands. In a few years, the purpose was accomplished, and the Black vote was suppressed. But mob murder continued.”

Alleged threats, violence or accusations of disrespect toward white women were often the excuse for the mob murders that white authorities continually claimed to be powerless to stop when white mobs amassed for lynchings—sometimes announced in newspapers in advance—as Gov. Dorsey did in his excuse-making letter to the Colored Welfare League. In Oxford, William Steen was lynched due to a rumor that he was bragging about an affair with a white woman, researchers found. And white men lynched 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 because he supposedly flirted with a white adult woman.

Author and public historian Michelle Duster, the great-granddaughter of Ida. B Wells, discussed her iconic relative—the subject of her latest book—and the problematic way in which history is told in the United States with the Mississippi Free Press on Friday.

“The way that this country, overall, has chosen and continues—pretty much with few exceptions—to tell the history of our country, is in a way to make white people comfortable,” Duster said. “And so that makes it difficult for Black people to fully express our pain.”

‘She Used the Truth as a Weapon’

Duster’s latest work focuses on the life and impact of her great-grandmother, who challenged the deadly status quo in her own time and fought for justice most of her adult life—including against lynching and the excuses used to justify it.

“She was putting names to stories and names to statistics. She was putting context into what was happening,” Duster previously told The Guardian about Wells’ anti-lynching, myth-busting work. “Without what she did, it was pretty much ‘OK, this person committed a crime, they got what they deserved.’ (Wells) said, ‘No, they did not commit a crime.’ The narrative of the mainstream media at this time was very different from the reality she found on the ground.”

Anyone seeking to effect change in their communities today can employ Wells’ truth-to-power methods, Duster said. “She used the truth as a weapon,” the author said of her great-grandmother. “She knew she couldn’t get justice through the legal courts, so her tactic was to get justice through the court of public opinion.”

Or, as Ida B. Wells herself put it in the 1909 speech: “Why is mob murder permitted by a Christian nation? What is the cause of this awful slaughter? This question is answered almost daily—always the same shameless falsehood that ‘Negroes are lynched to protect womanhood.’”

She meant white women, of course.

Donna Ladd contributed to this report.