Warning: Parts of this story contain graphic descriptions of racist violence.

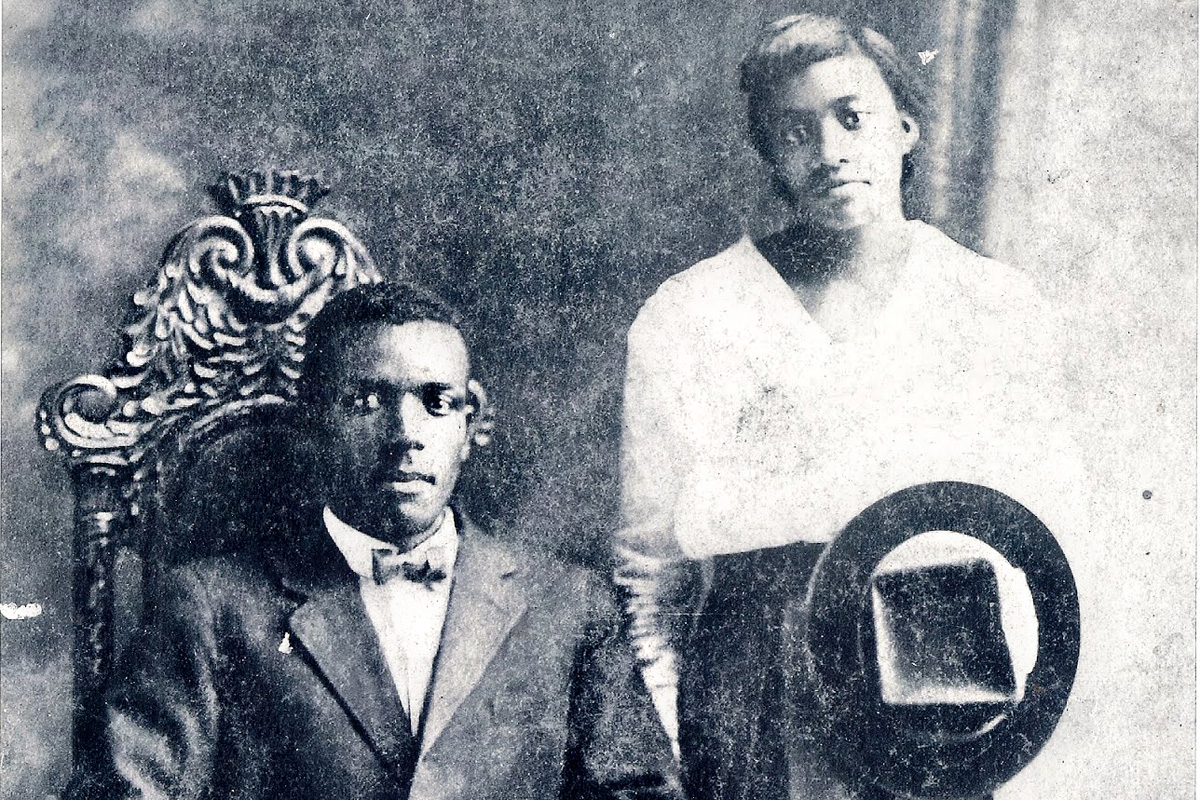

Lamar “Ditney” Smith was home with his wife, Annie, out in the county west of Brookhaven, Miss., when the phone rang early on Aug. 13, 1955. When Smith put the receiver down, he told her he had to go into town, and he soon picked up a stack of papers and headed out.

Those papers were absentee ballots. Smith, then 62, was campaigning against incumbent Beat 5 Lincoln County Supervisor J. Hugh James and on behalf of challenger Joe Brueck—who was later the local sheriff in the 1960s. Both candidates were white and, in the Aug. 2 Democratic primary, had made it to the upcoming runoff election on Aug. 23. Black people didn’t have much voting power then due to Jim Crow laws and racist voting restrictions in place since the 1890 Constitution, but Smith’s campaign work could get James unseated.

That meant that the Black voting activist with his absentee-ballot strategy was a clear threat to the balance of political power in Lincoln County. White folks had already threatened the Black businessman to stop meddling in politics and even put him on a hit list for his efforts, his wife and NAACP investigators would say later.

Smith knew he was risking his life to help Black Mississippians build stronger futures for themselves and their progeny, but that didn’t turn him around, as his family members recounted in Keith Beauchamp’s 2005 documentary, “Murder in Black and White: Lamar Smith.” Like many Black men of the time, Smith had returned from his tour of duty in World War I confident and motivated to keep fighting at home for equality and upward mobility for African Americans in Mississippi.

On that August Saturday morning, 66 years ago this month, Lamar “Ditney” Smith set out for the courthouse in Brookhaven, the county seat that has always prided itself on its “old southern charm,” modern sophistication, and as a place to settle down, live a good life and raise children.

Jet Magazine reported in 1955 that wife Annie would later regret not asking Ditney who was on the other end of the phone on their last Saturday morning together.

Where He Lay Bleeding

Lamar Smith arrived at the Lincoln County Courthouse as dozens of people milled about on the lawn, there to socialize and take care of business inside the county building as folks did on Saturdays then. Walking up to the steps on the north side of the courthouse carrying his ballots, Smith encountered three white men. The triumvirate stepped up to block Smith, telling the veteran he could not enter the government building, and he argued back.

Suddenly, the local sheriff would soon learn, a white man named Noah Smith pulled out his .38-caliber pistol and shot Ditney Smith in the ribs under his right arm at close range near the northeast corner of the chancery clerk’s office. His target then stumbled for about 30 yards on the lawn and fell into a nandina bush, where witnesses then just stared. Theologian Tex Sample, then a 20-year-old local white man near the courthouse when Smith fell, told Keith Beauchamp that white people wouldn’t allow anyone to try to save Smith, with one of them calling out, “Nobody carries that n****r to no hospital!”

Once Smith was dead, someone draped a sheet over him, and he just lay on the ground for hours, a haunting precursor to images of Michael Brown’s body left in the street for four hours in Ferguson, Mo., 59 years to the week later.

The next morning in Mississippi, the combined Clarion-Ledger/Jackson Daily News Sunday page 1 blamed the victim in its headlines: “Links Shooting of Negro With Vote Irregularities: DA Says Illegal Ballots Voted in the First Primary.” It followed with a subhead: “No Witnesses to the Murder Have Been Found.” The report stated, with the passive voice obscuring responsibility, that the shooting “was linked” to voting irregularities and that Smith “was mysteriously shot and killed,” despite dozens of witnesses.

“The slain Negro, who was once convicted of bootlegging,” the paper continued, was also under suspicion over “an unusually heavy number of absentee ballots” cast in the primary. The prior charge of bootlegging piled onto the white-owned papers’ case that perhaps Smith deserved his fate, as southern journalists often did then (and sometimes do now).

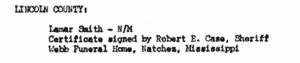

Lincoln County Sheriff Robert E. “Bob” Case saw local man Noah Smith leaving the courthouse covered with the Black man’s blood after the murder, he would soon say. But he didn’t stop him then. The FBI revealed many years later in 2010 that an informant stated that “subject Noah Smith was an active supporter of the incumbent county supervisor and objected to the victim encouraging people to vote by absentee ballot. As a result, Noah Smith and the other two subjects argued with the victim and then shot and killed him.”

The Ledger/Daily News story also revealed that Sheriff Case was planning to interview the bloodstained man, who indeed surrendered the same day that report came out. The McComb Enterprise-Journal reported the same day that District Attorney E.C. Barlow had charged Noah Smith with murder.

‘You Won’t Be Able to Stay Here’

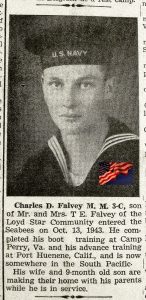

Two days after Noah Smith surrendered, Mack Eugene Smith and Charles Denver Falvey gave themselves up while claiming their innocence. The men were freed on $20,000 bonds each pending the grand jury decision. Their surrender came after a closed-door coroner’s inquest with 12 witnesses, which concluded that the three men had indeed been in an altercation with Lamar Smith that resulted in him dying from a gunshot wound.

The trio, though, would never go to trial for Smith’s murder. No one would agreed to testify to a grand jury convened the month after the murder, or to a second one called by newly elected District Attorney Mike Carr in early 1956, about what they’d seen on that bloody Saturday. Tex Sample said in Beauchamp’s film that a friend of his told him this about Smith then: “that (n-word) deserved to die.” Sample, who lives in Kansas City, Mo., wanted to speak out against the murder then, he said in the film, but his family advised him against it.

“‘If you say anything, you won’t be able to stay here,’” Sample’s family told him. “So I didn’t say anything.”

With no witnesses, and inevitably immense pressure to let it go, the prosecution’s case against the three men would fade away like other wink-wink investigations to prosecute white killers of Black people during the Jim Crow era.

The lack of justice for Smith was similar to the murder of Rev. George Washington Lee in Belzoni, Miss., in the Delta just three months before. The successful grocery-store owner was vice president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, which taught Black entrepreneurship, self-reliance and political involvement, thus threatening white control. After Lee was shot in the face and killed while driving the night of May 7, 1955, no one was ever arrested. White Humphreys County Sheriff Ike Shelton claimed it was just a car crash and that pieces of lead found in his head were actually dental fillings. Black doctors autopsied Lee, however, finding that a rifle shot had ripped off the lower left side of his face.

Not surprisingly, Lamar Smith had attended RCNL meetings in Mound Bayou, and he was at Lee’s funeral, where his wife Rosebud Lee opened the coffin, as Emmett Till’s mother did less than four months later, with both grieving women showing the world what race terrorism looked like.

White men in Money, Miss., kidnapped 14-year-old Emmett Till on Aug. 28, 1955, two weeks after Smith’s murder. In a barn in Glendora, Miss., they brutally beat the boy; shot him in the head; used barbed wire to tie his body to a large cotton-gin fan; and dumped him into the Tallahatchie River. An all-white jury acquitted those men within weeks even though they would admit killing the boy later to Look magazine, even as the article’s author agreed to conceal others involved in the murder.

The year after Brown v. Board of Education told southern schools to integrate was a busy year for white panic, terrorism and intimidation in Mississippi, not to mention heartbreak and fear among Black residents.

‘Some Race Trouble’ Downtown

Noah Smith was a 57-year-old white farmer, Mack Smith was a 45-year-old oil field worker, and Charles Falvey a 32-year-old farmer born in Wesson in Copiah County. All three suspects lived in Beat 5 in the vicinity of the Loyd Star community northwest of Brookhaven, and they’re all buried in the same part of the county today. Sheriff Case attended Loyd Star School as well.

At least by country-distance standards, Lamar Smith was their neighbor. His Caseyville farm was seven miles northwest of Loyd Star, the busy hamlet where Beat 5 votes were cast. All the men might even have been friendly, maybe even hunting together with dogs Lamar Smith trained in one of his businesses.

But it was Lamar Smith’s voting efforts that were a serious threat to white dominance and that was bound to cause local white people to lose their minds, and their morality, as they worked to stop advancement that threatened their supposedly superior status in any way. White supremacy is based on zero-sum logic: They gain, we lose.

By 1955, and unlike many Black men in Lincoln County then, Lamar Smith was self-reliant, as Beauchamp learned from family members. With strong business acumen, he lived and ran a successful farm not far from Loyd Star and the adjoining Macedonia community. He ran his dog-training business and belonged to several lodges in the area, where he indeed hunted and fished with both Black and white men, his family would later say.

Due to his success and lack of fear, Smith represented the “uppity” threat, as most white Americans then thought of African Americans who weren’t afraid of them or who were achieving success. He didn’t bow before white folk; he considered himself their equal; and he called white men by their names, not “Mr.,” as Beauchamp’s documentary shows.

Lamar Smith is now buried in a small cemetery next to his wife with a tombstone honoring his military service a few miles from Loyd Star on the way to Caseyville, a former plantation community. Caseyville is roughly 18 miles, give or take, from Brookhaven and was originally called New Scotland due to its settlers’ origins. Early Caseyville was still in Copiah County back before the Reconstruction government created Lincoln County there in 1870 from parts of Lawrence, Copiah, Pike, Franklin and Amite counties. The feds named it, of course, for the fallen president white southerners despised because he ultimately upended the area’s slavery economy, which relied on free labor.

Census and slave records show that Lamar Smith’s people hailed from that area, including his father Levi and mother Harriett Humphrey Smith. Local researchers found that his uncle Anderson Mitchell (later Smith) was enslaved on John Mitchell’s plantation first, one of many enslaved people in nearby Jefferson County, and then leased out to Archibald Smith’s nearby Shadyside Plantation. Archibald Smith was one of at least five Smith slave owners in Jefferson County then.

Like nephew Lamar Smith would later do in World War I, genealogy researchers indicate that Anderson Mitchell/Smith became a soldier—a private in the 58th Regiment of the United States Colored Infantry, created from the Black 6th Mississippi Infantry—which mustered near Natchez in 1864 and mustered out in 1866. The soldier was among U.S. troops that marched to Gillespie’s plantation in Louisiana in August of that year to face Confederates on his own quest for freedom.

Brookhaven’s History of Extrajudicial Murders

Ninety-one years after that soldier’s journey from Natchez, though, Black freedom still was not welcome in charming Brookhaven and its surrounding country enclaves after generations of brutality to ensure that African Americans lived in fear and compliance.

The County of Lincoln, formed under a watchful federal eye in 1870, did not have the same level of Ku Klux Klan presence in its post-Civil War formative years as many counties in other parts of the state. Michael Newton writes in “The Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi: A History” that there was an early Brookhaven klavern there, terrorizing Black people at night, until Lincoln County formed. After Reconstruction ended, local white terrorism came in the form of White Caps, violent paramilitary “clubs” based in Amite, Copiah, Franklin, Lawrence, Lincoln and Marion counties in the region.

The White Caps engaged in a variety of vigilante activity, specializing in whippings. That violence included many Black laborers and sharecroppers in decades following the Civil War with White Cappers wearing Klan-esque getups and declaring it “illegal” for businesses to hire Black workers. Much of their beatings, violence and scare tactics helped cut off potential spigots of advancement and wealth for generations of Black workers and farmers at a pivotal time in Mississippi history.

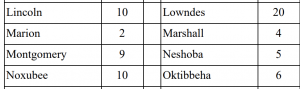

Well into the 20th century, like most if not all Mississippi towns and counties, Brookhaven had hosted vicious lynchings with prominent white citizens involved in various ways. The Equal Justice Initiative has confirmed 10 Lincoln County lynching victims in its county-by-county reports on lynchings across the United States.

Even when not participating, local white Brookhavenites at least did far too little to stop them or identify and prosecute the murderers and lynch mobbers, who would flow in from multiple counties to help when news of a planned lynching went out in advance, often in the state’s newspapers. The violent events might be public hangings of one or more Black people or a different kind of murder such as Lamar Smith’s shooting, but the result was the same.

‘The Fearful Look on His Gorilla Face’

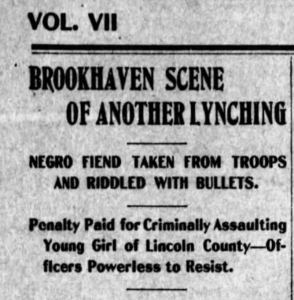

Early the morning of Feb. 10, 1908, when Ditney Smith was still a teenager, a lynch mob of men poured in from other counties to join a hunt for blood. The white gang met armed deputies and militia guards who were transporting Eli Pigot from Jackson to Brookhaven to stand trial.

Mattie Williams was a white daughter in a prominent family who accused Pigot of sexually assaulting her at the post office in Ruth, a small town southeast of Brookhaven, and the Black man was arrested after he fled the area. But before Pigot could stand trial, a lynch mob led by the girl’s father, J.P. Williams, took the suspect forcibly from the officers, who traded blows with them for a few minutes before giving in.

The mob then kicked and beat Pigot with the father stabbing him first. Next the swarm riddled the suspect with bullets, twice, the Newton (Miss.) Record reported. They then hanged the Black man’s body from a telegraph pole less than 100 yards from the Lincoln County Courthouse where Lamar Smith would die on the lawn 47 years later. The crowd of an estimated 2,000 white people again filled Pigot’s body with bullets as he hung from the pole.

The Newton paper, in what it called a “dispatch from Brookhaven,” was gleeful as it detailed Pigot’s grisly lynching (the second in Brookhaven that year), calling him a “Negro fiend,” a “black brute” and declaring the “penalty paid” for the alleged crime. “Piggot (sic) showed by the fearful look on his gorilla face that he knew his death was near,” the Feb. 13, 1908, news report stated.

The Associated Press started its story the same day with an assumption that the lynched man was guilty during a time when yet-unproved sexual assault of white women was a constant excuse to kill Black men across the South and beyond.

“Eli Pigot, a negro, who criminally assaulted Miss Williams in this county a few days ago, was taken from the custody of a Jackson military company and a posse of deputies and hanged today,” the AP report stated as fact although the rape was never proved, a common reporting practice among southern journalists then. AP added: “Pigot assaulted Miss Willliams, a young white woman, several days ago and was to have been tried today for his crime.”

No one was ever arrested or tried for the murder of Eli Pigot.

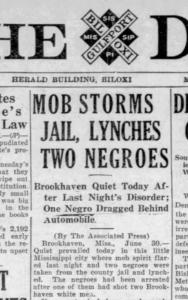

Then, on June 30, 1928, a Brookhaven mob lynched and mutilated Black brothers James and Stanley Bearden after a fight with white brothers Claude and Caby Byrnes, who ran a local service station. Mississippi news reports including the Daily Clarion-Ledger reported that Caby Byrnes “tackled” James Bearden because he owed him $6 for an unpaid bill. Bearden left after the assault and returned with his brother, reports said, and the fight continued with the other Byrnes brother hitting the Black man with a shovel, who hit him back with a piece of iron. Stanley Bearden then backed up and started firing his pistol, striking one of the Byrnes boys in both legs and his shoulder.

The Black men were soon locked up in the county jail. That night, several hundred Brookhaven citizens stormed the jail, using an acetylene torch to break into the cage where the Beardens were held, the Associated Press reported then. They took them both about a mile and a half south and hanged James Bearden from a tree and shot him to death as his brother watched, the Lincoln County Times reported on July 5, 1928. The mob then took Stanley back into Brookhaven, tied him to the back of a truck and dragged him “through the streets of the city and through the negro quarters,” followed by a parade of vehicles, the report recounted. The murderers then hung what was left of his body to a different tree.

“Then the bodies were mutilated and the mob dispersed,” the Associated Press reported the day after the lynching. “The town has quieted down and is going ahead just as if nothing had happened,” a separate AP dispatch added. A coroner’s jury determined that the killers could not be identified.

‘The Law of Nature Is On Our Side’

Two white attorneys, T. Brady and J. A. Naul, as well as Rev. Paul Hardin, pleaded with the mob to not lynch the Bearden brothers, The Clarion-Ledger reported on June 30, 1928.

Brady was likely Tom Brady, the father of Judge Thomas Pickens Brady who would become infamous in 1954 for his virulently racist “Black Monday” speech months after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education anti-segregation decision. He then turned the talk into one of the nation’s most racist books, and then a pamphlet sold in bulk.

“You can dress a chimpanzee, housebreak him, and teach him to use a knife and fork, but it will take countless generations of evolutionary development, if ever, before you can convince him that a caterpillar or a cockroach is not a delicacy,” Brady bellowed about Black people in his first “Black Monday” address in Greenwood, Miss., to the Sons of the American Revolution.

It wasn’t personal, though, wink, wink. “This is not stated to ridicule or abuse the negro. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with the caterpillar or the cockroach. It is merely a matter of taste. A cockroach or caterpillar remains proper food for a chimpanzee,” Brady added.

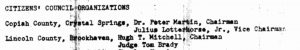

The Brookhaven judge was already on the executive committee of the racist States Rights Party (also called the Dixiecrat Party) when the Brown decision dropped. He then became a major player in the Citizens Council movement of prominent white business leaders and power brokers that sprang up after the Brown decision to resist efforts to end Jim Crow and segregated schools. Brady’s primary role was eruditely spreading the model of white supremacy, thus frothing up white crowds to do the dirtier work of white resistance.

“The organization’s founders embraced sophisticated white leadership as an effective alternative to more violent organizations, like the Ku Klux Klan, believing that civic and business leaders would keep violence at bay,” Millsaps College historian Stephanie Rolph, the author of “Resisting Equality: The Citizens’ Council, 1954-1989,” writes.

Prominent people like Judge Brady targeted white people who did not follow its lead. Brady, a Yale and University of Mississippi graduate, would become a Mississippi Supreme Court justice in the 1960s while he was still a Citizens Council barnstormer. The strategy was to both spread propaganda and collect “intelligence” on anyone supporting civil rights, Black or white; they then threatened their jobs and livelihoods, or even got banks to pull their loans, Rolph explains.

In essence: Speak up for civil rights or against murders such as those of George Lee or Lamar Smith and lose your pathway to paying your bills now and building wealth for you and your family in the future. Or, get run off, as Tex Sample’s family warned him in 1955.

Or end up in a grave.

Distancing from Violence … Sort of

In Judge Brady’s talks inside and outside the state, he would distance from the violence of the KKK and lynch mobs, but then kind of justify it. “I wouldn’t join a Ku Klux—I didn’t join it—because they hid their faces; because they did things that you and I wouldn’t approve of,” the judge told the Indianola Citizens Council in 1954. But, he added, “I am not going to find fault with a man who did. Every man looks at the proposition (of integration) not in the same way.”

Likewise, Citizens Council leader John Satterfield, a prominent Jackson attorney from Port Gibson who served as the president of the American Bar Association, did the same dance around violence, Newton reported in his history of the KKK in Mississippi. Satterfield acknowledged in a speech in Greenville, Miss., that “the gun and torch” was one of three ways to keep segregation in place, even as he personally found violence “abhorrent.”

And now-deceased William J. Simmons, the eventual Jackson-based leader of the Citizens Councils of America (who years later started the Fairview Inn in his family home in Belhaven, now under new ownership), liked to spew fighting words that “an all-out war is being waged against the white race,” while tracking the position of local white people on civil rights.

White men like Byron de la Beckwith, who killed Medgar Evers in 1963, were members of both the CC and the KKK, and the men believed to have killed George Lee in Belzoni were both Council members. The Council had been targeting his grocery store, and another owned by local NAACP President Gus Court, to stop their activism. Like with Lamar Smith, violence often came after boycotts and threats failed to stop what racists then liked to call “agitation.” Court was also shot for his activism but lived, with no arrest forthcoming.

Not to mention, Council members were known to pay the legal fees of men accused of race violence.

In the Black Monday booklet, Brady weaponized the Citizens Council movement with virulent lies about Black people being biologically inferior, comparing them to apes and chimpanzees. Debunked “scientific” racism was a primary tenet of the Citizens Council’s “racial integrity” ethos against miscegenation, meaning sex or marriage with anyone who wasn’t white. That would lead to the “amalgamation of the white race,” he and other prominent racists warned.

“You cannot place little white and negro children in classrooms and not have integration,” Brady warned in his 1954 Black Monday speech. “They will sing together, dance together, eat together and play together. They will grow up together and the sensitivity of the white children will be dulled. Constantly the negro will be endeavoring to usurp every right and privilege which will lead to intermarriage.”

Leaving Black people in their rightful place was the correct choice, the Brookhaven judge said in speeches across the U.S.

“If left alone, (Brady) said, the South will work with the Negro since ‘the South alone understands him,’ and will solve the problem of living together,” the Brookhaven influencer told a Rotary Club gathering in scenic Estes Park, Colo., as reported then by the Estes Park Trail newspaper. That talk was about a month before Lamar Smith was killed back home, with Brady framing the same core racist beliefs inside a more genteel tone outside the South than in his fiery “ape” speeches about Black inferiority on home soil.

In a world without the Internet for fact checking, in 1957 Brady assured the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco that his heart was pure. “I want you to distinctly understand that the South does not hate the Negro. … Among the finest characters I have ever known are Negroes,” he assured them before making a case for maintaining segregation and white supremacy.

Brady didn’t mention in Colorado that, in the apartheid system back home, any person of any race who disagreed would be boycotted, harassed, threatened or worse. The man doing it just might be wearing a tie, though, instead of a white hood.

Eastland Hype on Eve of Murder in Brookhaven

In 1955, U.S. Sen. James O. Eastland—the son of a man who had led a violent lynching in 1904 in Sunflower County—was also on the talk circuit, firing up white resistance to integration and Black advancement. The night before Lamar Smith’s murder on Aug. 13, 1955, the Delta senator gave a highly publicized anti-integration speech in Senatobia in north Mississippi on behalf of the Citizens Council, calling for white people to ignore laws protecting Black rights.

“On May 17, 1954, the Constitution of the United States was destroyed because of the Supreme Court’s decision. You are not obliged to obey the decisions of any court which are plainly fraudulent sociological considerations,” the U.S. senator boomed with newspaper reporters present.

Four months after Smith’s murder, Eastland spoke in Jackson at a boisterous Citizens Council rally, saying “we have nothing to be ashamed of” and that fellow white supremacists should band together to use tax dollars to maintain white supremacy. (Segregation schools like Brookhaven Academy, which met in the historic Whitworth College until its building was finished, indeed got state vouchers when they formed in or around 1970 when the U.S. Supreme Court finally put teeth into its 1954 Brown decision.)

At the Jackson talk, Eastland echoed Brady’s claims about Black people being inferior to whites like them. “The law of nature is on our side,” he proclaimed. Like Brady, the U.S. senator loved to refer to the “sociological Supreme Court,” a nod to what they believed was the high court’s misguided biological experiment of race-mixing.

As Judge Brady used his urban sophistication and sophistry to fire up white supremacists in speeches from Lincoln County to California to New Jersey, he was an active circuit judge through the 1950s, hearing criminal cases and sentencing the guilty in Brookhaven. That meant that he could have presided over the trial of the three white men accused of killing Ditney Smith, had they ever made it to trial.

Brady used his public office to lend his racist crusade credibility. The pamphlet of his Black Monday followup talk in Indianola listed on the cover that he was the 14th District Circuit Judge from Brookhaven. Attendees could buy 250 of the pamphlets for $10.

But it was the 1950s in Mississippi, the place Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would nine years later call “a desert state sweltering in the heat of injustice and oppression.” Like many heroes of the era, Lamar Smith did the work anyway, right in the faces of powerful men like Brady and Eastland, even as the upstanding men of the Citizens Council right in his hometown agitated for white resistance with deniability built in for themselves.

Smith’s niece Lizzie Louise Scott said in Beauchamp’s documentary that her Uncle Ditney knew he could be killed for the cause. “He said he would die for the sake of us, umm hmm,” Scott said about her hero uncle.

‘Showing Truth and Love of God to the World’

The Macedonia Baptist Church cemetery, a couple miles northeast of Loyd Star out in Lincoln County, is a veritable sea of Smiths and Cases, including the primary suspect in Lamar Smith’s murder, Noah Smith. Sheriff Bob Case, the man who saw Noah Smith leaving the courthouse in 1955 covered with blood as Lamar Smith lay dying, does not rest there, however. Although he is from Brookhaven and attended Loyd Star School, the World War II veteran who arrested Smith, Smith and Falvey back then is buried in nearby Franklin County.

The Macedonia Smiths have intertwining family trees with one line of the ubiquitous name marrying into another—many wives were Smiths before and after marriage, presumably from different blood lines—and the same first names are often scattered through both sides.

Noah Smith is buried alongside his wife Lou Smith Smith near a family plot of tombstones near the center of the Macedonia church cemetery. The county’s and later the FBI’s prime suspect—whom Ancestry.com indicates was born Isham Noah Smith—lived nearly 20 years after Lamar Smith’s murder. He died at age 77 on June 17, 1975, a date FBI documents confirm.

His tombstone says under his name, “Father, let thy grace be given.”

Macedonia Baptist Church is the home church of U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith whose husband Michael Lamar Smith hails from the area, near where they still live and run their ranching interests. She has taught Sunday School there and headed the church’s personnel department, and her husband is a deacon who has served as Sunday school director, the Brookhaven Daily Leader reported.

The Macedonia Baptist Church, today run by younger members of the community, shares its mission on its website: “To bring glory to Jesus Christ by being equipped with the gospel, empowered by the Holy Spirit, and engaged in showing the truth and love of God to the world.”

Outside the church, the large cemetery is a time capsule where town meets country, past meets present, history meets politics. It is haunted, one might say, by the moral question of how far should the community go to show the truth of Lamar Smith’s death to the world.

Standing over Noah Smith’s grave, it is easy to ponder the inexcusable tragedy of certain lives being deemed more valuable than others, in a county that mutilated Black men accused of violence against whites, but still perpetuate furtive cover-ups and vows of silence among white citizens who allowed a Black neighbor to bleed out in the public square.

Where the Innumerable Dwell

Filmmaker Beauchamp—who helped get the Emmett Till case reopened and is now a producer of “Till,” an upcoming feature film—started unraveling the Lincoln County puzzle years back, figuring out that the sister of Sen. Hyde-Smith’s husband married the grandson of Citizens Council lead propagandist Judge Brady in that southern gothic way Mississippians know well. Susan Smith Brady is buried in the Macedonia cemetery with a double tombstone awaiting Thomas Pickens Brady III to lie by her side. There is no indication that younger Brady family members share the same putrid beliefs as elder Judge Brady, however.

Brady III’s infamous grandfather is buried in the ornate Rose Hill cemetery in town alongside Brookhaven founders, business leaders and influencers. It is a block over from Brookhaven High School where many of the town’s white leaders and shakers graduated, including Judge Brady in 1920. That was back before integration led to Brady’s racist agitating and, after they lost the battle, a segregation academy opening in 1970 where younger generations of Hyde-Smith’s husband’s family attended, as did their daughter.

In fact, Susan Smith Brady scored the first two points in Brookhaven Academy’s John R. Gray Gymnasium, her obituary tells us. Hyde-Smith herself attended now-closed Lawrence County Academy when it opened, where she was photographed in cheerleader pictures with a Confederate flag. In 2018, the year Hyde-Smith joined the U.S. Senate, Brookhaven Academy had two Black students of 477 total; the city is majority-Black, as is the public high school now.

In the charmingly ornate Rose Hill memorial park, Judge Brady’s tombstone eulogizes a “Jurist—Author—Statesman” with a small American flag in the marble vase. Words on the marker hope of joy for him “where the innumerable dwell.”

Fifteen miles away toward Caseyville, grass is growing up around Lamar Smith’s tombstone honoring his service in World War I, a monument that seems to be slowly sinking into the ground.

Also read Brookhaven native Dick Scruggs’ call for a historic marker to Lamar Smith on the lawn of the Lincoln County Courthouse. He was 9 years old in Brookhaven when his mother told him there had been a “lynching at the courthouse.”

The above story is part of the MFP’s Mississippi Race Violence Project. Filmmaker Keith Beauchamp, whose research is referenced in this article, is on the advisory board of the Mississippi Free Press. Watch his documentary, “Murder in Black and White: Lamar Smith,” “Murder in Black and White: Rev. George Lee” and “The Untold Story of Emmett Luis Till.”