Julia Wright was 12 years old when she discovered “Black Boy.” She met her father’s memoir in his home office where he kept all his books. Richard Wright and his family were at this time living in Paris. On this night, Julia’s parents had gone to the theater as she satiated her curiosity and appetite.

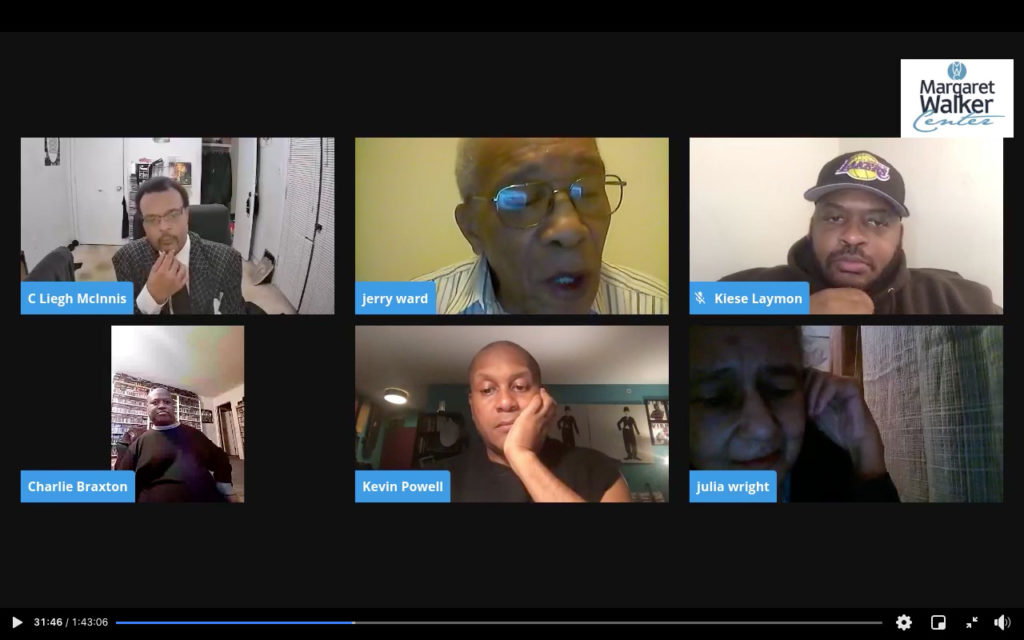

“I was allowed to free range all his books. I could choose any book. There was no forbidden book. That was his law,” Julia Wright recounted on Nov. 12 to an esteemed panel gathered virtually to celebrate the memoir’s 75th birthday.

Jackson State University’s Margaret Walker Center hosted “The Black Boy Conversation”, a Zoom panel discussion, with poet and professor C. Liegh McInnis, writer, editor and professor Kiese Laymon; poet, scholar and professor Jerry Ward Jr.; poet, playwright and journalist Charlie Braxton; journalist, poet author and activist Kevin Powell; and journalist, essayist and poet Julia Wright assembled to discuss the impact of “Black Boy” on them as Black people and Black writers.

“That was the day I took the (book) from the shelf. I remember it was midnight blue under the dust cover,” Julia Wright said.

After sneaking into her parents’ room to grab some caramel candies, Julia took her items to her room and huddled under the blankets. But she didn’t make it far into her reading, she said.

“I never got past Chapter 2 where he says, ‘I got one orange for Christmas.’ I jumped out of bed and spit up the caramels, missing that beautiful first edition by inches. I didn’t take up that book again until I was in my teens,” she said.

Laymon: Understanding the Fire Inside Himself

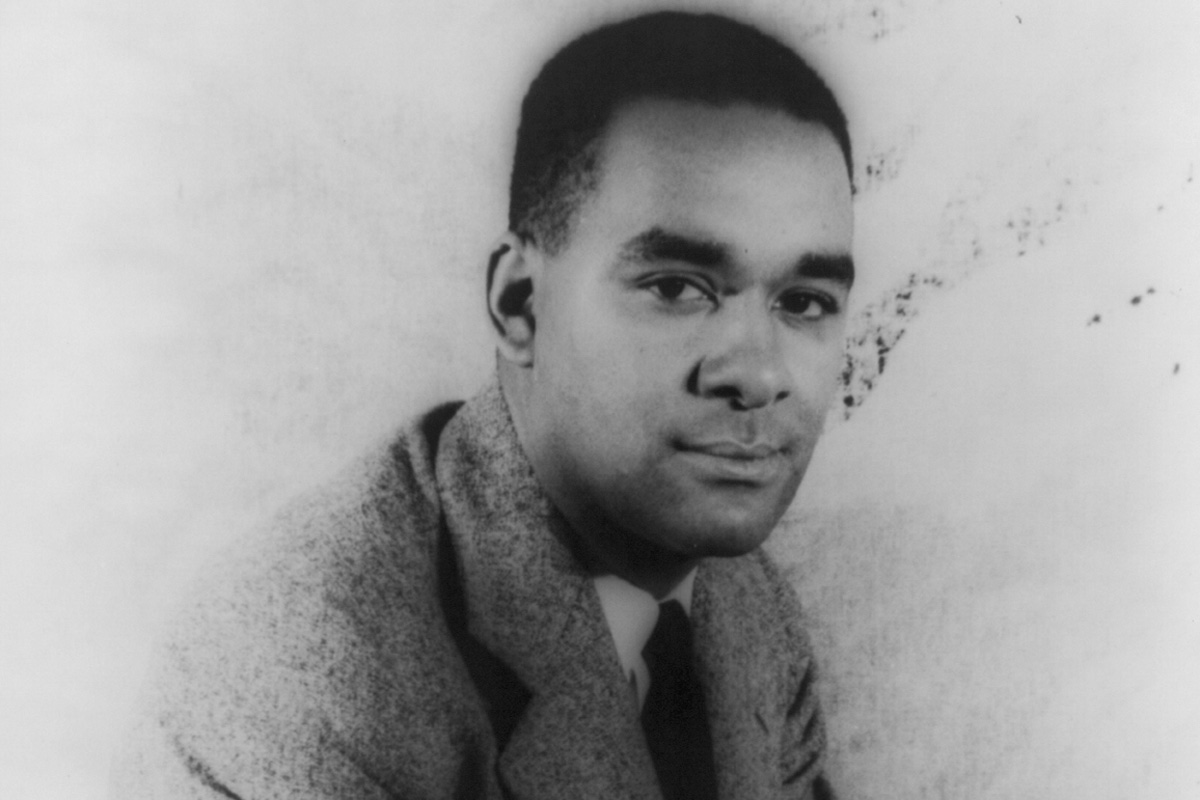

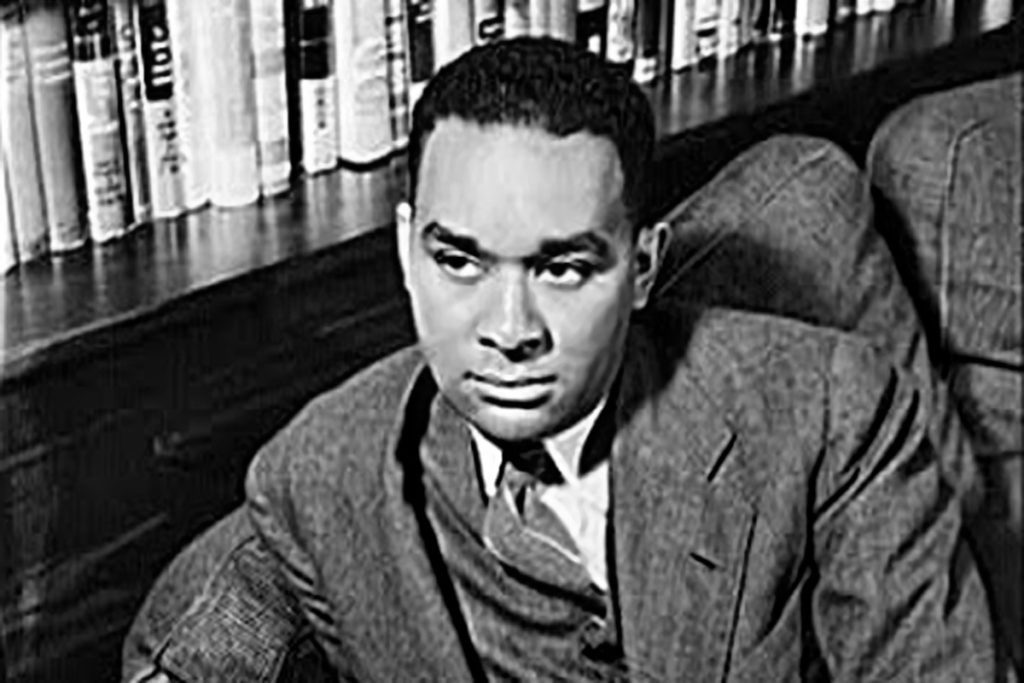

Richard Wright was born east of Natchez in Roxie, Miss., in 1908 and became a composer of poems, short stories, dramas and novels that hinged on themes surrounding the plight of African Americans in America during the 20th century. “Native Son,” “Uncle Tom’s Children” and “Black Boy” are among his more notable works.

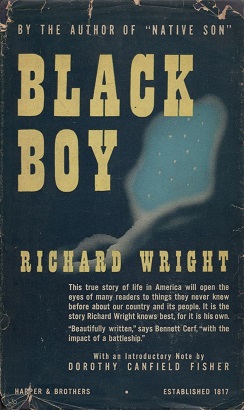

“Black Boy” tells Wright’s story in the South across Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas, as well as his migration to Chicago where he began his writing career and got involved with the Communist Party. The memoir received great acclaim for his honest picture of racism in America that leaves an indelible impression on readers.

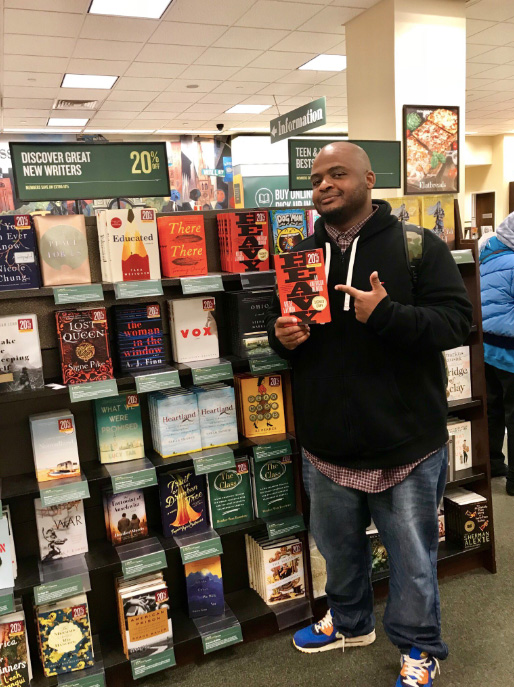

Kiese Laymon, whose memoir “Heavy” is about growing up in Jackson, was but a child himself when he encountered “Black Boy,” around the same age as Julia. He snuck and read it when his mother went to bed, he said during the panel.

Wright’s story was a reckoning with the fear and anger Laymon felt as a young Black boy. “Fear and anger were things I felt, but I did not have models of how to contemplate that fear and anger or really to think about the consequences of the fear and anger that was bubbling up in me,” Laymon iterated.

The mark “Black Boy” left on Laymon led him to urge his white teachers to teach Richard Wright, but to no avail. Wright’s initial influence on Laymon was less about becoming a writer and more about understanding fire inside himself to fight like that he found in rappers like Tupac and Biggie and pop-culture figures such as Scarface.

‘How Words Can Empower the Struggle for Liberation’

Kevin Powell, Charlie Braxton and Jerry Ward Jr. found Wright during their college years. Braxton, a McComb native, said “Black Boy” would have been a great book to read in middle school or high school, but he didn’t discover it until he attended Jackson State University.

“It moved me in such a way that I wanted to be a writer, but I knew I couldn’t write like him. But it taught him the power of words and how words can empower the struggle for liberation,” Braxton said.

Jerry Ward, who grew up on the Gulf Coast, said he wasn’t sure he appreciated “Black Boy” when he read it in college, but it stuck with him. He could identify with the teasing from family and classmates that Wright experienced for wanting to read. Ward was awarded the Richard Wright Literary Excellence Award from the Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration in 2011.

“Both Wright and I, in our very different ways, said no. We have to be who we are,” Ward said. “We have to be who we understand ourselves destined to be. Fortunately, we took different paths, but we turned out OK,” he said.

Kevin Powell, the writer and activist, said he didn’t know Black writers existed for the first 18 years of his life, but Richard Wright was the first Black writer he fell in love with. Though he came of age in New Jersey, Powell recognized that Wright’s upbringing drew some parallels to his own experiences as a Black boy who grew up in poverty and who had a love for reading.

“I felt like Richard Wright through ‘Black Boy’ was teaching me as a Black male how to navigate racism, even though he was born in 1908. ‘Black Boy’ saved my life,” Powell told the panel.

‘Cannot Kill His Genius’

Richard Wright kept it real, regardless of sometimes hurting feelings. “Black Boy” was originally titled “American Hunger” and was written in two parts with one section detailing his early life in the South and the second part covering his time in the North in Chicago.

The second section would become “American Hunger,” which the Book of the Month Club rejected for being “not commercially viable,” Julia Wright said during the panel. Her father was very honest in his assessment of the North and refused to herald it as the mecca for black people from a racist South.

“American Hunger” would not be published until 1977, 32 years after “Black Boy” was released in 1945 with an alternate ending. Yet, Wright’s decision to remove an important portion of his book and life story haunted him due to societal pressure, his daughter said.

“There should be a book written sooner or later about how much Richard suffered deeply about being dismembered from his creativity in that way,” she said. “I watched him cringe when he found out that his heiko in which he had poured his entire self, his blues, his remembering of the South, his hopes that he would live … and they had been rejected,” Julia Wright said.

Jerry Ward Jr. read a February 1940 Book of the Month Club document in which writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher described her thoughts after reading the “Black Boy” manuscript. “Richard Wright stings your nerves taut,” she wrote. “He communicates his anguish to you as by a piercing cry of pain in your physical ears, yet he finishes his book with disciplined self control and power to spare, so that in the last pages he sweeps his readers out of from the concrete indefinite with their crushing weight of literal fact into a spacious realm of thought poetry, beauty and understanding.”

Ward called Fisher’s assessment “a neo-liberal northern view,” one that could not grapple with Wright’s honest depiction of the North that saw its share of race riots in cities like New York and Chicago, he said.

“You have to look at all of the USA, and you have to confront, painful as it is, the kind of systemic racism that allowed that book (“Black Boy”) to be cut,” Ward said. “It was part of an 6 of white people in the north who wanted to laugh at those people on Tobacco Road. Those people Faulkner wrote about.”

Charlie Braxton said Wright taught him the meaning of truth, speaking it to power and how to analyze the world he inhabits. And Kiese Laymon learned the importance and value in an interior life while organizing and fighting for issues.

“To be a Black writer, to be a writer that is woke in every sense of the word and is committed to telling the truth, it is to have a life that is very difficult,” Powell added. “No matter what they tried to do to Richard Wright, you cannot kill this man’s genius.”

Bypassing Food for Books

Richard Wright was no materialistic man because his hunger was of a different kind—several kinds, in fact. His daughter said she recognizes his hunger pangs when she goes back through the pages of “Black Boy.” There’s a hunger for his father, an intellectual hunger, a hunger to bridge the distance between him and his mother, she listed.

Being full metaphysically versus being full with materialism was the question posed to the panel, a notion that Julia Wright has “emotionally rejected.”

“These different hungers mixed and fought and, in the end, he found that what satisfied him was what he found in books. The knowledge,” she said. “The answers to the questions were in the books he found, and that was his quest. The search for the intellect was much more important than materialistic things.”

Richard Wright died with $800 in his bank account, she added.

Braxton recounts bypassing food to spend his money on books when he was in college. He finds it is more important to feed the mind and the soul, he said.

“It doesn’t mean anything if I have a full belly or money if my cousin or neighbors don’t have anything. The struggle from what I gathered from Wright was to use your intellect, find everything you can, learn everything you can,” he said.

‘Biting Back Isn’t Enough’

Jerry Ward said Richard Wright showed that if one has the ability and will to investigate, then they should. They should ask questions they cannot get the answers to, and those responses will inform other questions.

“It’s educational malpractice to go through school and not see a single Black, Brown or woman writer until I got to college. He gave me an imagination. I was eating junk food,” Powell said. “I was eating violence masquerading as American history. He gave me a holistic view of himself, and it was like looking into a mirror. I’m actually alive.”

Wright taught Laymon that you have to bite the white hand that thinks it is feeding you because that hand is attached to a mouth that wants to consume you.

“You have to bite back, but biting back isn’t enough. He taught us that you have to describe the shit that you’re biting. When you bite back and we fight back, we have to describe that,” Laymon said. “I think that that kind of hunger, the hunger that is created when you bite back or when you refuse to be consumed, I think that’s a particular type of hunger.”