Water bottles, empty and crushed, line the asphalt walking track around the Choctaw Central High School football field. A trail of dried sweat leads to fresh droplets of blood on the pavement as Jon McKinney rests on his knees, gasping for air.

He alternates between wiping away the blood around his nose and lifting an inhaler to his lips to help regulate his breathing. A substitution player takes his place on the field, but after a few minutes McKinney stands and rushes back onto the grass to help his team, TvshkaHomma, face Beaver Dam in the first round of the World Series Stickball Championships at the 72nd Choctaw Indian Fair on Wednesday, July 6, 2022, in Choctaw, Miss.

Nicknamed “The Little Brother of War,” stickball is a centuries-old sport. Native American tribes would use the game to determine political matters, such as land disputes, instead of succumbing to war. Currently, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians publishes the current guidelines for the sport, and the yearly world series, hosted on original Choctaw lands during the annual fair, is considered the sport’s premier event.

Beaver Dam is up 5-0 on TvshkaHomma partway through the second quarter, which is no surprise to Roger Amos, a Choctaw Tribal member who wrote a personal essay about the sport for the Mississippi Free Press in 2021. His stepfather played for Beaver Dam, which calls the Pearl River community home. He is a solid Bok Cito fan.

“This is sort of like David and Goliath,” Amos says of the battle between Beaver Dam and TvshkaHomma.

During the series’ open night, Amos is dressed in red, their team colors, for the pregame ceremony for Fallen Tushka, which means “warrior” in the Choctaw language, where each team honors their players who died in 2021 and early 2022.

Amos says players are referred to as “warriors” due to the game’s role in replacing war, as the players represent warriors in battle when they compete. Any former player who has passed away over the last year is honored.

‘It Should Be a Blowout’

Stickball is a Native American sport where two teams of 20 to 30 players use sticks, named “kabocca,” to throw a small, orange ball at a pole that stands about 12 feet high. Each team defends a pole while simultaneously trying to hit the other team’s pole one hundred yards away with the game ball. The World Series Stickball games have four quarters, each lasting 15 minutes. The clock only stops for injuries or penalties.

Physical contact is allowed—except for early or late hits, hits below the knee, and clotheslines—as long as the ball stays within bounds. Players push, shove and even throw each other to the ground to get the ball. Apart from a few who wear goggles, the players do not typically wear protective gear.

“It should be a blowout,” Grant Williams, a Choctaw tribal member working as security at a gate near the Beaver Dam benches, says. He notes that regardless of the projected outcome, people still enthusiastically come to attend the games.

“Every year, when there is a big concert,” Williams says motioning toward the amphitheater across the road, “everyone still fills the stands to watch the stickball.”

Beaver Dam rotates players in from the sidelines who have been anxiously pacing the track waiting for their opportunity. TvshkaHomma takes advantage and scores their first goal. Before long, they score two more, only trailing 7-3 at the beginning of the fourth and final quarter.

Through the first three quarters, hundreds of Choctaw tribal members float among the home bleachers of the football field in a joyful mood, shouting and dancing with each score. Their team is living up to expectations. After TvshkaHomma narrows the difference to only four points, however, the stadium quiets down, anxious about how close the newcomers can make the game.

TvshkaHomma is from Oklahoma and is relatively new to stickball compared with the Mississippi Choctaw Band of Indians. Unlike Williams and Amos, who first played the game as young children, many members of TvshkaHomma learned the game later in life. Oklahoma teams first competed in the championships in 2009, and their performance has earned them invitations back to the competition each year.

The comeback fails to continue, however.

Beaver Dam scores three more points in the first 10 minutes of the fourth quarter, making the score 10-3 and ending on a mercy rule. Dozens of Beaver Dam squad members fill the field and congratulate TvshkaHomma on a hard-fought game.

(See more photographs from the Choctaw Indian Fair’s World Series Stickball Championships and stickball exhibition games in the gallery at the end of this story.)

Changing of the Crown

As Choctaw Indian Princess Shemah Crosby glides across the stage during her farewell at the Choctaw Indian Fair Pageant, tears well up in her eyes. Crosby has served as an ambassador of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians for the past year. She has attended multiple pageants, given presentations at schools about Choctaw culture and visited every Choctaw tribal community in Mississippi. The tribe owned most of current-day Mississippi before the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, signed in Noxubee County, brought removal of most Choctaw people to Indian Territory, now called Oklahoma, along the Trail of Tears.

“If you would have told a 7-year-old me that I would grow up to be a Choctaw Indian Princess, she would have been too shy to even talk to you,” Crosby says in a speech that plays during her walk. “I remember pageant night. I was sitting backstage after I was done with my traditional wear, feeling so proud of myself, more than I ever had before, and when the time came and my name was called, everything froze and felt unreal.”

Crosby stops on three sides of the stage, where hundreds of people from the crowd have lined up to give her small gifts and hugs and to take pictures. Between greetings, Crosby smiles and wipes away tears. So many people want a moment with Crosby that the pageant technical staff finishes the audio of her speech and plays two more songs before the announcer tells the crowd the pageant needs to move on so that they can crown a new princess.

For the previous two hours, 12 contestants compete in various categories before a panel of three judges. In “personal presentations,” each contestant gives a short speech about themselves, including details about their childhood, their current obligations and future aspirations, and their goals if selected as princess.

“I am thankful for my parents to have passed down this tradition to me,” Charlita Gibson says as she lifts a pair of moccasins worn during Choctaw dances, “because it has made me who I am today: a young Choctaw woman who loves to walk and dance in the footprints of my ancestors.”

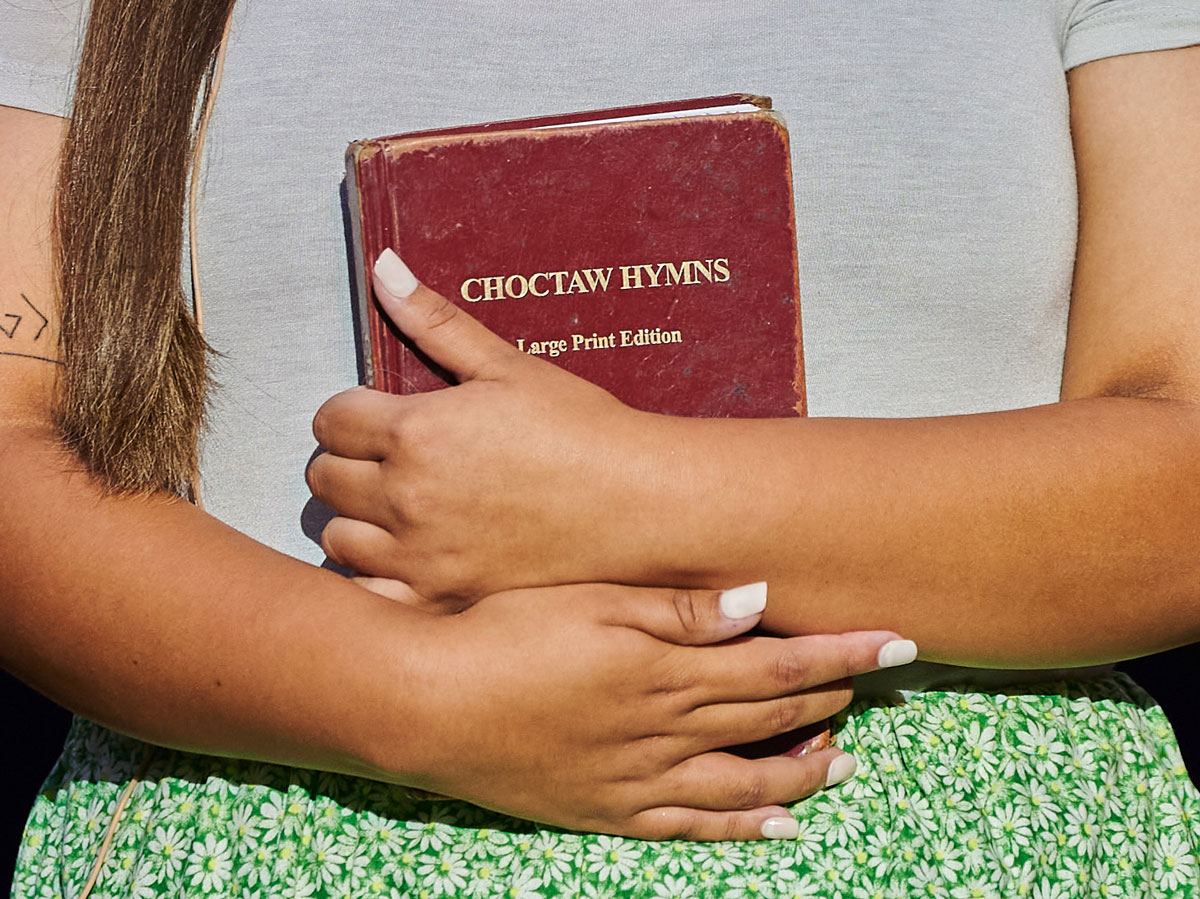

Contestant Cadence Nickey sings a gospel song in her native Choctaw language, highlighting the importance of keeping the language alive.

“The Choctaw language is the heart of my people’s identity, but sadly our language is slowly fading. And when the language is lost, so is the culture,” Nickey says. While growing up, she sang gospel songs in Choctaw with her mother and grandmother.

The next two categories of the pageant are the traditional dress and on-stage interview questions. Each contestant, wearing a traditional Choctaw dress, walks to the microphone and blindly selects a judge to give them a question.

Judges ask Kyla Farmer how she thinks her generation differed from previous ones in solving community problems.

“I feel as though my community and my generation have become more productive and more active in our community,” she responds. “Thanks to social media helping bring awareness to our problems, we are successful in answering them with solutions.”

Shortly after 10 p.m., all 12 contestants return to the stage, where Choctaw Tribal Chief Cyrus Ben and Choctaw Indian Princess Shemah Crosby give them their awards. Kyla Farmer receives first runner-up, Catherine Jim receives second runner-up, Jordan Mack wins Miss Congeniality, and Tayla Willis wins most photogenic.

Everyone in the crowd rises to their feet in anticipation of the naming of the new Choctaw Indian Princess: “Representing the Tucker Development Club, contestant no. 4, Cadence Raine Nickey,” emcee Talia Steve announces.

The crowd roars with excitement, and Nickey steps forward. Chief Ben adorns her with the red winner’s sash, and former Choctaw Indian Princess Crosby crowns her.

Chief Ben and Crosby step away, and Choctaw Indian Princess Cadence Nickey makes her first walk with the crown, a spotlight following her each step.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, your 2022-2023 Choctaw Indian Princess, Cadence Nickey,” emcee Talia Steve shouts, “Thank you, and good night.”

See more photographs from the pageant, stickball and social dancing at the 72nd Choctaw Indian Festival in the gallery below.