Multiple gunshots rang out during lunch break in downtown Jackson on Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022. The State of Mississippi-funded Capitol Police, who said the shots came from a fully automatic weapon, discovered a white Infinity riddled with bullets and found a man and a woman with gunshot wounds at the scene. Officers took the two victims, who were in stable conditions, to a nearby hospital.

The incident happened hours before Gov. Tate Reeves presented his 2022 State of the State address on the steps of the Mississippi Capitol, a few blocks away.

Reeves cited the gunfire event while asking for increased Capitol Police spending, reeling out the capital city’s recent homicide numbers—128 in 2020 and 156 in 2021. “And just today, less than four blocks from where we sit, less than one block from the governor’s mansion, we had a shootout in the middle of the day,” he said. “That is unacceptable.”

“That is why I’ve championed an expansion of the scope of our Capitol Police force to support local law enforcement and to bring peace back to Jackson,” he added. “That’s why I proposed doubling the size of our Capitol Police force, so there will be more boots on the ground as you perform your shifts in the Capitol Complex Improvement District.”

In 2021, the Mississippi Legislature transferred the Capitol Police from the Department of Finance and Administration to the Department of Public Safety. The police force’s role changed from protecting the capitol complex and state properties to having jurisdiction over a 8.7-square-mile Capitol Complex District in downtown Jackson.

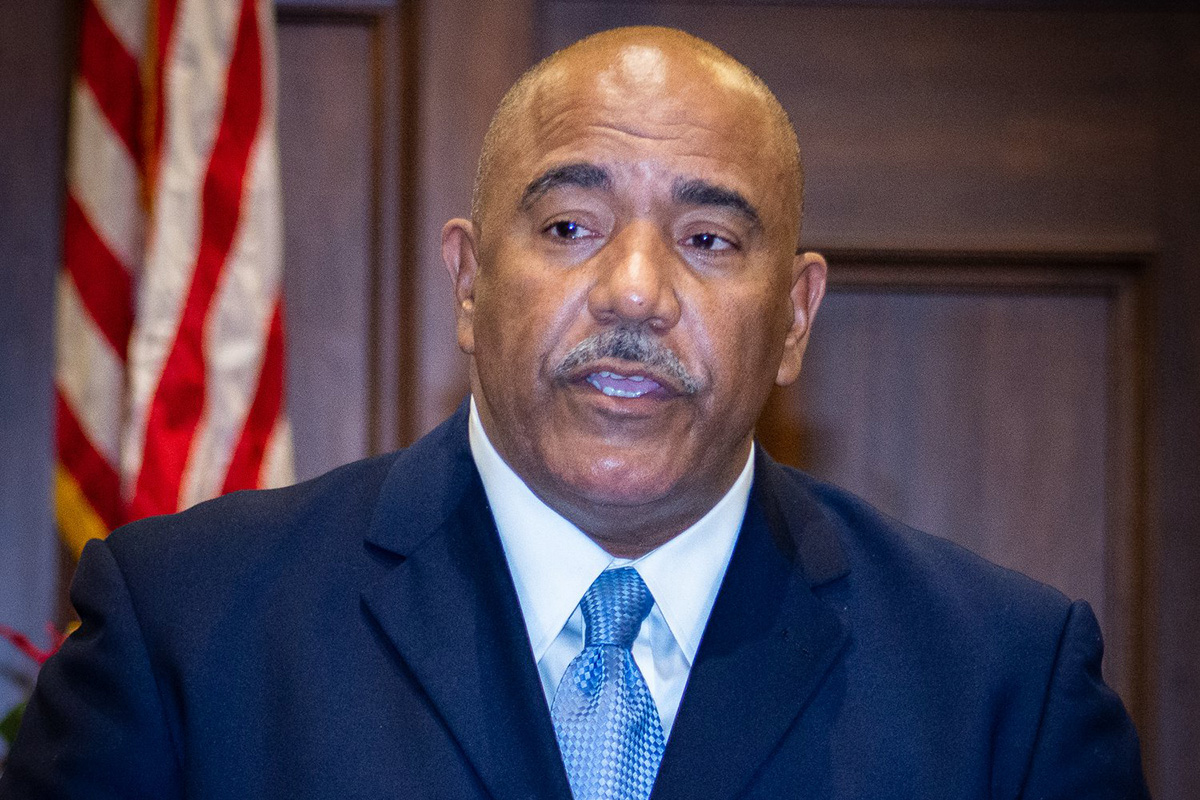

Department of Public Safety Commissioner Sean Tindell said in July 2021 that there were 81 Capitol Police officers as of then.

Jackson Senators Suggest Crime Solutions

Two days after Gov. Reeves’ presentation proposing the doubling of Capitol Police, five state senators representing parts of Jackson held a press conference at the Capitol—Sens. Sollie Norwood, D-Jackson; John Horhn, D-Jackson; David Blount, D-Jackson; Walter Michel, R-Ridgeland; and Hillman Frazier, D-Jackson.

They outlined a four-pronged legislative plan they argue will help deal with rising crime in the city.

The senators’ prevention ideas focused on arrests, prosecution and locking up suspects. Apart from increasing the number of Capitol Police, the lawmakers advocated for increasing the number of district attorneys in Hinds County, getting more judges to cover the backlog of cases and providing $600,000 for a municipal misdemeanor holding facility.

Sen. Norwood told the Mississippi Free Press in a Feb. 1, 2022, phone interview that their ideas will assist the capital city and Hinds County in curbing crime. “So all those things that we’ve had some conversations about, we’re just trusting that the process will move from conversations to appropriation, to actual addressing of the needs that we see here in the city,” he said.

The same day, Sen. Horhn told the Mississippi Free Press at the Capitol that the Legislature has budgeted for 50 additional Capitol Police officers. “They can be deployed throughout the Capitol Complex Improvement District and any other places where an agreement is made between them and the Jackson Police Department to cover all the areas of the city as well,” he added.

“We gave the Hinds County DA two additional ADAs this past fall, along with one investigator,” he added. “The request is for another two permanent ADAs, plus eight additional temporary ADAs. The whole purpose of that is to give them some help in dealing with the backlog of cases that are before them.”

The county jail is under intense federal pressure to repair conditions and facilities at its facilities that leads to violence and suicides among the locked-up accused not yet convicted of crimes, and likely seeds increased crime and violence on the outside, experts warn. But Hinds County and state officials have allowed the backlog, which largely affects Black detainees, to linger and fester for years. On Friday, U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves held Hinds County in contempt for doing too little to repair years-long conditions in the Hinds County Detention Center in Raymond.

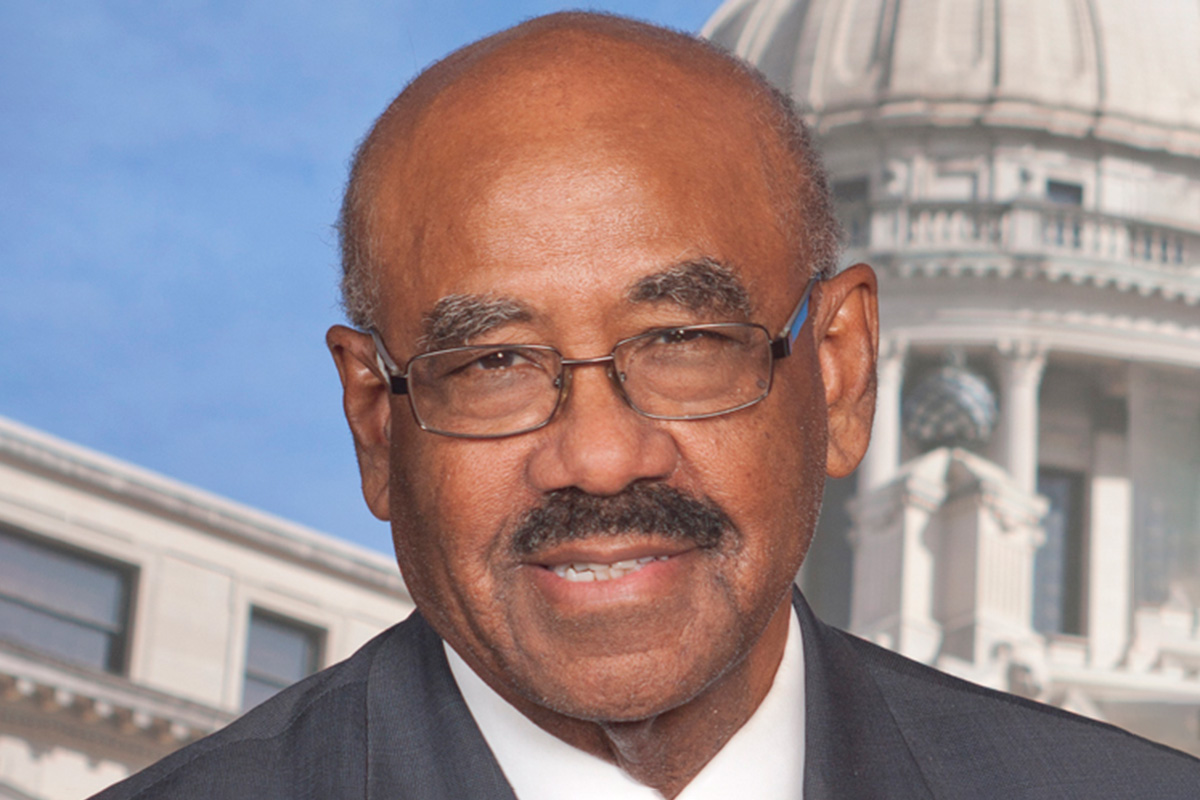

Judge Green: State Shares Responsibility for Jail Backlog

Hinds County Circuit Court Senior Judge Tomie Green Senior Judge Green said in 2021 that based on her decades-long experience in Hinds County in the legal profession, the problem of the backlog of cases had only grown. The State of Mississippi shares the responsibility, she said.

“The volume of cases has increased, and early on when I was with the Legislature, we were trying to get the Legislature to underwrite additional judges for Hinds County, and they didn’t,” Green said then.

While a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1992 to 1998 before her election to the bench, Green recalled the debates on increasing the number of judges for Hinds County and the objections to it. “At that time, I think one of the questions was not only is it that the State has to pay—the State only pays for the judges—it’s an unfunded mandate to your county,” the senior judge said.

Horhn said he expected Mississippi Chief Justice Michael K. Randolph to recommend the number of special judges for the county soon.

“We put two special judges in place about a year and a half ago, and they’ve done wonders in moving the caseload through the process,” the senator said in the interview. “We’ve already seen great results, but we know that we need to have some additional judges, and we expect that the Supreme Court chief justice’s recommendation would be for another two to three special judges.”

Special judges began working in Hinds County in July, 2020, Randolph said in February 2021. At that time, they had closed 597 cases, and dismissed an additional 170 cases.

The Mississippi Free Press emailed the Administrative Office of Courts Public Information Officer Beverly Pettigrew Kraft asking for information showing the difference those judges have made. She responded, saying she had forwarded the response to AOC Director Greg Snowden. There has been no reply as at press time.

A Misdemeanor Holding Facility

Sen. Horhn explained that initial estimates show that $600,000 will be required to “put the municipal jail back in service.”

“There’s got to be a long-term solution established for the Hinds County Detention Center, which is under a consent decree right now,” the Jackson senator said. “And we will try to help that effort as much as possible, but we need a temporary holding facility for misdemeanor cases, and we expected that the municipal jail would serve that purpose.”

Sen. Blount told the Mississippi Free Press by phone on Feb. 2, 2022, that he sees a place for a misdemeanor holding facility in the city.

“(W)e don’t have enough jail space in the county to deal with the problems that we have right now, and the county doesn’t have the funds to fix it,” he said. “So we’re trying to help with that.”

Misdemeanors are low-level crimes, and those locked up are usually there because they cannot make bail. Across the country, cities and counties are rolling back on jailing people accused of misdemeanors.

City Out of Jail Business Since 1993

In 1993, the capital city—under the leadership of Mayor Kane Ditto—signed an interlocal agreement with Hinds County to stop operating a jail and for the county to handle all its jail needs.

“The nature and the scope of the contract contemplated by this agreement is to enable the parties to house detainees in a common detention facility by closing the Jackson City Jail and utilizing the Hinds County Detention Center as consolidated detention facility and repository for both City and County detainees,” the 19-year-old document said.

The parties cited two Mississippi state codes as the basis of the agreement, which indicated that the sheriff is the county jailer and that he looked forward to having the 600-bed Hinds County Detention Center in Raymond under construction at that time, as the operational base. The center has, however, been under a consent decree since 2016, and a federal court on Friday, Feb. 4 has found it in contempt, paving the way for moving it into receivership.

“The sole purpose of this Agreement is to establish a consolidated detention facility in which detainees may be housed,” the 1993 agreement continued. “It is acknowledged by the parties that the City will close the City Jail when Hinds County opens the adult detention facility located in Raymond, Mississippi, on or before April 1, 1994.”

Hinds County District 2 Supervisor David Archie told the Mississippi Free Press by phone on Feb. 2 that the parties can reverse the agreement if needed.

“Jackson does not have the power or the authority to run a jail because we are under an agreement that was signed many years ago that Hinds County would be in the jail business,” he said. “Now we would have to take a vote on the board of supervisors in order to give Jackson that power again, to run their own jail, and Jackson would have to accept it.”

“If that could help solve some of these issues and some of these problems and some of the crime problems that we are having, certainly we would love for that to happen.”

The agreement provides for a possible future amendment through the parties’ mutual consent.

District 3 Supervisor Credell Calhoun, in an interview with the Mississippi Free Press on Feb. 2, stated that the $600,000 for the municipal jail was a move from Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and House Speaker Philip Gunn.

“They are trying to help in any way that they can,” Calhoun said.

The board president explained that the federal consent decree governing the county jail prohibits it from managing additional facilities, adding that the Mississippi Department of Justice would not allow the Hinds County Detention Center to hold misdemeanor offenders. In 2020, then-Hinds County Sheriff’s Office spokesman Tyree Jones, who was elected sheriff in November 2021, affirmed that the Raymond facility does not take misdemeanor offenders, except those involved in domestic violence. He referred to the 2016 consent decree as the basis. But a search of the document did not yield any such detail.

“So Jackson is kind of in a pickle right now,” Calhoun said. “They are in a very difficult situation, and then they don’t have any way to house misdemeanors.”

“Misdemeanors, according to the (Jackson police) chief, are causing a lot of problems for them,” he added. “I understand that COVID is causing some of it, but we’ve got to learn to get along,” he said. “It’s more than just COVID in Hinds County.”

“As a result, we must take action.”

City of Jackson Wants Own Misdemeanor Jail

Since last year, Jackson’s Chief of Police James Davis has campaigned for Jackson to have its own misdemeanor jail. On Nov. 9, 2021, he spoke at a town hall at Holy Temple Baptist Church at a crime summit that Ward 4 Brian Grizzell hosted, with Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba in attendance.

“We must have a holding facility so that we can hopefully put these individuals in time out,” Davis told those gathered at the event. He asked them to lobby the city council members and board of supervisors to “make it possible for the Jackson Police Department and the City of Jackson to get back into the jail business.”

“We must get back into the jail business,” he repeated at the meeting, emphasizing his words.

A few days later, on Nov. 15, 2021, Chief Davis spoke at a Hinds County Board of Supervisors meeting in support of Supervisor Archie’s proposal to set aside $1 million for a holding facility in Jackson. The motion eventually failed to pass.

“Because we did not have a misdemeanor jail, since March of last year, we have released over 3,000 misdemeanors in the City of Jackson,” Davis told the board. “We give them a piece of paper. They don’t show up in court, and they are terrorizing the city of Jackson, and it is an easy fix.”

“The easy fix is to send a clear-cut message to these violators out there: If you commit a crime in the City of Jackson, you will no longer be free on bond; you will go to jail, and that’s my plea,” Davis said. “My phone rings 24 hours a day, citizens are crying out, officers are pleading with me, ‘Chief, we need a jail because we have repeated offenders terrorizing the city of Jackson, and all we can do is give them a filed release sheet of paper and hoping they show up in court.'”

The prosecution process for misdemeanor offenses in Mississippi begin with citation, governmentregistry.org said. “Depending on the nature of the offense, the accused person may be allowed to go home with the citation containing the summary of the charges brought against him or her and the date and time of the first hearing in the Law Court in Mississippi,” the website added. “In some cases, the person may be detained within the premises of the law enforcement agency from where he or she is charged to court.”

Mississippi misdemeanor crimes include possession of marijuana more than 1 ounce but less than 8 ounces and smoking of same, reckless driving, driving under the influence, and driving while intoxicated, prostitution and obscenity, computer crimes, criminal mischief, criminal trespass, disorderly conducts and other crimes including child abuse and domestic violence.

In the Wednesday interview, Archie said that he supports setting up the municipal misdemeanor jail. “We need resources to go ahead and establish a misdemeanor holding facility where we can arrest more misdemeanor offenders, so they don’t go back to the community and continue to commit those serious misdemeanor offenses, like a shooting in the community and the neighborhood.”

Archie said the jail would not be holding people long-term because of the nature of misdemeanor offenses. “So yes, we need those beds; anywhere between two and 300 would be sufficient,” the district supervisor said. “We need to take them through the process of being arrested, fingerprinting, having to bond out of jail, having to take out time, and having to sit.”

“Right now, we are issuing citations in the city and the county and are not admitting most misdemeanor offenders into the county jail,” Archie added. “And perhaps that will slow down a non-serious offender, and they don’t progress to a serious offender.”

Archie only mentioned shooting inside the city limits as an example of a misdemeanor that falls under that category, but that does not include shooting at another person, which would be a felony.

Legislative Initiatives Focused on Police, New Jails

Apart from the four initiatives that five Jackson senators detailed in late January, the Mississippi Legislature is taking different bills regarding crime under consideration during this legislative session.

In House Bill 890, Reps. Earle Banks, D-Jackson, and Bo Brown, D-Jackson, ask for $15 million to defray the cost of Hinds County constructing a new jail facility near the Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center.

Sens. Norwood, Horhn and Frazier are seeking authorization for the county to institute a $15-million bond for the repairs of the Hinds County Detention Center through Senate Bill 2950.

Via HB 1265, Reps. Banks, De’Keither Stamps, D-Jackson, and Ronnie Crudup Jr., D-Jackson, have asked Jackson for $10 million to build “a detention center for detaining misdemeanor offenders.”

Rep. Debra Gibbs, D-Jackson, in HB 1543 requests $7 million to “assist the City of Jackson in paying the costs associated with the construction, furnishing and equipping of a real-time command center and related facilities, for the acquisition and installation of shotstopper equipment and systems action, and the installation of patrol operations technology for the City of Jackson Police Department.”

Sens. Norwood, Blount, Horhn and Frazier, in SB 2952, request $7 million for the real-time command center (2304 Riverside Drive), which launched in November 2020 and uses cameras across the capital city to assist in crime-solving.

Solutions Beyond Policing, Incarceration

In Senate Bill 2927, Sen. Frazier asks for $4 million from the coronavirus state fiscal recovery fund for Hinds County to build “a youth program to prevent crime via conflict-resolution strategies.”

The one-year funding, the bill explains, is to partly defray expenses for a youth mental-health program. The aim is to prevent crime via conflict-resolution strategies and youth empowerment. Frazier suggested in the bill that increased escalation in violent crimes that young people have committed is directly attributable to the increased mental stress due to the pandemic.

BOTEC Analysis warned in a 2016 study on Jackson crime and violence that the Mississippi Legislature ordered and funded that increased policing, jails and incarceration can actually act as a precursor to worsen the trajectory of young people engaging in low-level crimes into committing worse violence later. Sen. Horhn was one of the backers of those reports—which state, city or county officials seldom cite when discussing crime-fighting—despite its half-a-million-dollar cost to state taxpayers. BOTEC also released reports on gangs in Jackson, public-school discipline (and channeling too many students into criminal-justice system) and systemic prosecution/court backlogs allowing long pre-trial detention.

Researchers warned in the BOTEC that many young people involved in crime have mental illnesses that often go untreated. The capital city and State of Mississippi are currently facing a lawsuit due to allowing children in Jackson ingest lead, a poisonous substance linked to mental illness resulting in increased criminality, for their entire childhoods.

The researchers advised programs and strategies such as Los Angeles’ Urban Peace Institute to prevent crime and violence long before police have contact with a young person, and confirmed that a small percentage of people in Jackson commit most crime and violence and recommended early systemic intervention for young people due to identifiable precursors to crime.

Mississippi Youth Media Project teenagers reported on evidence-based strategies to prevent youth crime in Jackson, and the Legislature’s BOTEC reports, in 2017, and held a series of youth crime circles through Jackson to discuss potential solutions, including options outside policing and jails, which do not get wide community buy-in or funding.

At a press conference on Jan. 31, Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba stated that his administration is considering establishing a fund for various organizations working in crime prevention to use to support their activities.

The initiative emerged last month after city officials hosted the cofounders of Chicago CRED, an acronym for Create Real Economic Destiny with Arne Starkey Duncan, former U.S. secretary of education under former President Barack Obama, and Laurene Powell Jobs, the founder and president of California-based Emerson Collective.

Chicago CRED focuses on street outreach, life coaching, workforce development, and advocacy and prevention to address gun violence in south- and west-side communities in Chicago.

It works “with community leaders, like-minded organizations, and hundreds of young men and women to radically reduce gun violence and bring hope back to Chicago,” the organization said on its website.

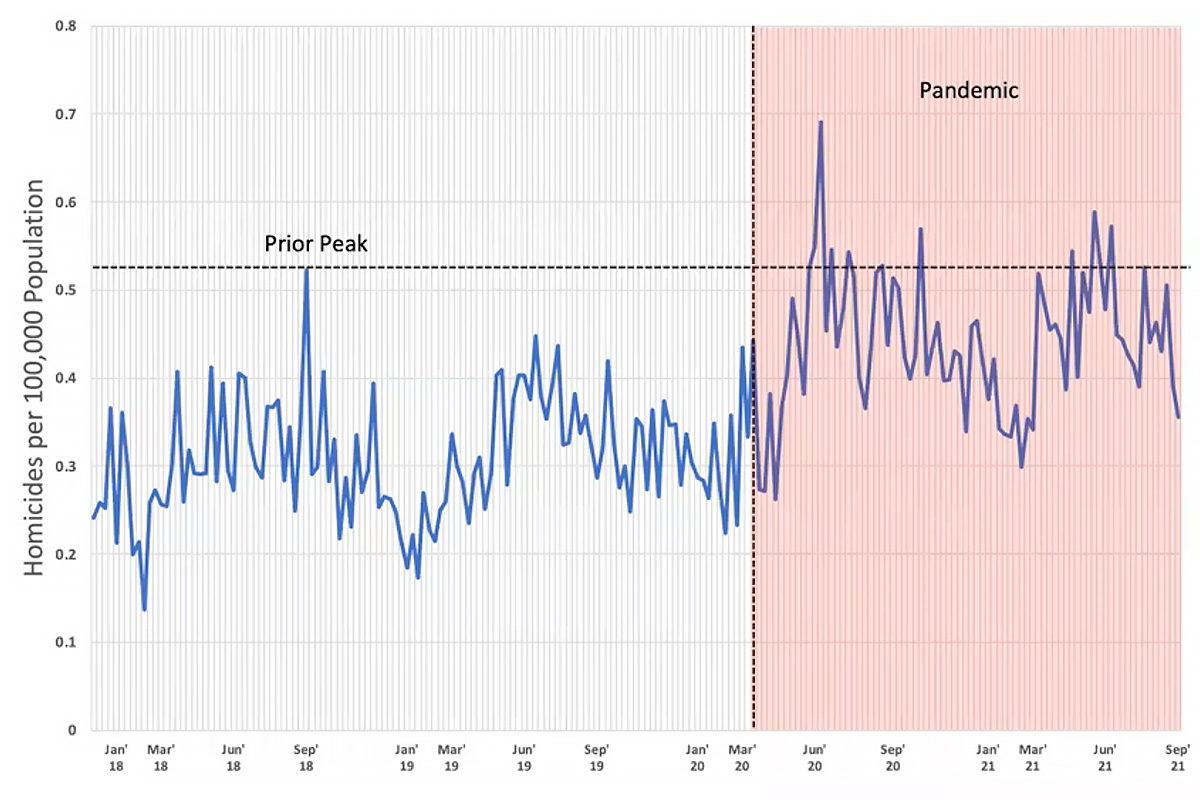

Against the backdrop of Gov. Reeves’ statement on Jan. 25 that the rate of homicides in Jackson is three times worse than in Chicago, Lumumba said Monday that the experiences that the leadership of CRED shared about other cities mirror what Jackson is experiencing.

“Jail capacity is an issue when you go to each one of these cities and hear that they’re experiencing the same things,” Lumumba said. “The demographic which has experienced violence at the highest rate is the exact same, city after city after city.”

“When we see this rise nationally, that’s not to say that we should be OK with it because we’re in line with everyone else,” he added. “That is to say that we should be able to identify what the common factors are that those cities are experiencing and then Jackson experiences it and how do we put our heads together in order to find those solutions.”

The mayor said he plans to meet with business leaders soon to “have a consistent line of funding that helps support” such an initiative.

“Another thing that I’ve learned in my discussions is how the structure of many of these youth programs exists in other cities and how some of the private sectors help support them,” Lumumba added. “What we really need is personnel; we need the funding to make sure that those programs are maintained, sustained, and they are ongoing. ”

“These have to be deeply rooted programs within these communities,” he said. “We need the support to make that happen.”

No State Support for Street Outreach

In January 2022, the Mississippi Free Press featured Strong Arms of JXN, an example of “street outreach” workers, which consists of formerly incarcerated individuals who are working to end the cycle of violence in the city by leveraging their experiences to influence the youngsters. The strategy is modeled on Cure Violence in Chicago and now many other cities, designed by an epidemiologist to prevent violence from spreading like a virus.

In a Twitter post on the day after the five senators’ press briefing, Donna Ladd, Mississippi Free Press co-founder, editor and executive director, challenged the senators to focus on supporting violence-intervention initiatives instead of fixating on jail beds and increased police numbers, as well as to read the warnings and suggested solutions in the BOTEC reports they ordered and funded.

Those suggestions included outreach workers and credible messengers—strategies to reduce crime and violence before police get involved in interactions BOTEC warns can lead young people to worse crime that community interaction and mentoring, especially by those who are formerly incarcerated, can prevent.

Sen. Horhn said on Feb. 2 that the capital city will have to make do with funding and grants from other sources for evidence-based interventions such as Cure Violence approaches as the Legislature focuses on funding more police and jail beds.

“We know that that needs to be addressed,” he told the Mississippi Free Press. “However, we are leaning on the city and the county to use their grantmaking abilities to go after federal funds as well as corporate funds to address the human-capital-development question.”

“There is a need for that; there’s no doubt about it, but the State’s efforts will be focused on what we call ‘traditional crime-fighting and public infrastructure,’” Horhn added. “We have one of the highest per capita murder rates in the country, and we have some of the worst infrastructures in the country, so those are the two primary areas that I plan to focus my attention on.”

City of Jackson Ward 7 Councilwoman Virgi Lindsay stated at the city council meeting on Feb. 1 that CRED is a “wonderful model” and that many nonprofits, philanthropists, and foundations throughout the city are engaged and concerned about violence reduction.

At the meeting, Chief of Staff Safiya R. Omari hinted at a proposed $700,000 fund for community groups involved in various aspects of violence interruption, mentioning the Strong Arms of JXN and others like Common Justice, Stewpot Community Services and local Boys and Girls Club branches as potential beneficiaries.

Only Thing People Learn from Incarceration is Resentment’

Urban Peace Institute Senior Consultant on Conflict and Violence Ron Noblett told the Mississippi Free Press over the phone on Friday, Feb. 4, that the senators’ plans were too little too late and a knee-jerk reaction.

“As usual, elected officials ignore or put off a problem until they can ignore it or put it off any longer, and then they panic,” the Los Angeles-based violence and policing expert said. “And when it has to do with violence, the panic inevitably goes to the thing of, ‘We need more cops; we need to suppress all this stuff, all this violence’—that has not worked for the length of its country.”

| The Council on Criminal Justice’s Violent Crime Working Group published “Saving Lives: Ten Essential Actions Cities Can Take to Reduce Violence Now” in January 2022. This is the report release event on Jan. 12, 2022. |

Noblett, who was an on-the-ground researcher in the capital city for the State-funded BOTEC reports, pushed back at the recourse to jailing misdemeanors, saying that other alternatives are fines and community service because of the negative consequences of incarceration.

“(The move is) based upon the assumption that people will learn a lesson by being incarcerated,” he said of the proposal to get Jackson a misdemeanor jail. “The only thing people learn from incarceration is resentment and how to be a better criminal.”

“Treatment and helping the situations that they come out of, and the source of the actions is the only answer,” he added. “Jails do not help; jails do not teach, jails do not train except how to be a bigger, a better criminal.”

“Basically, I think being locked up for a misdemeanor is counterproductive.”

Noblett said violence is a symptom of resource-deprivation and neglect.

“The real problem of Jackson is that it is isolated, it is cut off, and it has been, in my opinion, deliberately separated from any ability to help; it’s as if it’s slowly being strangled,” he added. “I believe that the whole basis of what’s taking place in Jackson is based on ignorance and race and racism of the surrounding county and the whites that control everything.”

“I believe those who are trying to deal with the problem are trying to use a bucket with holes in it to hold back the ocean,” he added. “The problem itself is people who are being set aside, ignored, treated like trash, and looked upon as things rather than as human beings.”

Noblett said that there is a need for attention to infrastructure and education in Jackson. “I do not deny that there are horrible problems of violence that have taken place, but again, these problems are a manifestation of the real problem and not the real problem itself.”

Violence Solutions for Cities

The Council on Criminal Justice’s Violent Crime Working Group published “Saving Lives: Ten Essential Actions Cities Can Take to Reduce Violence Now” in January 2022, which offers solutions to cities plagued by violent crimes, noting a rise during the COVID-19 epidemic.

The report advocated a commitment to tangible reductions in lethal and nonlethal violence. “Annual 10% reductions in homicides and non-fatal shootings are realistic goals,” the report said. It recommends a balance of carefully considered policing strategies and community-wide efforts to prevent violence in the future by enacting solutions to reverse the effects of socio-economic neglect among people most likely to commit it.

Cities should begin with a rigorous problem-analysis of violent crime to effectively reduce it, drawing on incident reviews, shooting data and law-enforcement intelligence to reveal the hotspots, the report recommended.

“Most critically, leaders must coordinate stakeholder activities focused on the highest risk people and places,” the report continues. “Plans should be practical and actionable, detailing concrete commitments: for key people and in key places, who will do what, by when?”

“Those individuals and groups at the highest risk of violence must be placed on notice that they are in great danger of being injured, killed, arrested, and/or incarcerated,” the report continued. “Supports and services must be offered so people have something better to say ‘yes’ to, but it must be made clear that further violence will not be tolerated.”

The report advocated for a focus on interventions and investments that will help change the nature of violent micro-locations and their communities.

“Finally, targeted investments and deployment of resources must be made to improve education, employment, healthcare, housing, transportation, and other socioeconomic factors that can give rise to crime and violence in the first place,” the report added.

Every city with high violent-crime rates should have a permanent section committed to reducing violence, with top leadership reporting directly to the mayor, the report continues.

“Within law enforcement agencies, chiefs and other top leaders must demand a consistent focus on preventing violence, not just making arrests, and on working with citizens and community partners,” it read. “Effective management also includes rewarding officers for outcomes like reduced victimization, rather than outputs like the number of pedestrian or car stops they make.”

“Similarly, non-law-enforcement leaders such as those running community-based anti-violence organizations should maintain a focus on anti-violence outcomes, not outputs such as services delivered,” the report added. “Chiefs and other top law-enforcement executives must require a continual focus on reducing violence and working with people and community partners.”

Other recommendations include emphasizing healing with trauma-informed approaches, investing in anti-violence workforce development, and setting aside funding for new stakeholders and strategies.

Ivey: Deal with Root Causes, Fund Crime Prevention Programs

Strong Arms of Jackson Co-director Benny Ivey similarly said in an interview on Friday, Feb. 4, with the Mississippi Free Press that the Jackson senators’ plans were inadequate because they address what happens after crimes have been committed and do not address crime prevention.

“We need funding to fund community programs and community members that can stop things from happening in their own neighborhoods,” said Ivey, the previously incarcerated Simon City Royals gang leader. “What they’re doing isn’t going to do a thing to stop anything.”

“It does not even scratch the surface of what we need to do in Jackson,” he said. “We need something in place that helps address the root problems of these young people in Jackson that makes them commit the crimes in the first place.”

He suggests supporting organizations in the city that work with young people like his organization and others like Operation Good and Safe Street Streets Cure Violence Program to put actual violence prevention in place.

“I would like to see more resources given to the community, given to community programs, community organizations, and partners within the communities that have the means of stopping violence from happening in their own neighborhoods,” he said. “Rather than funding programs that have been proven in other states to prevent crime, prevent shootings, instead of funding those programs, they want to fund more police officers that … are only supposed to be called on the scene, after the problem, after the shooting has already happened.”

The Council on Criminal Justice January report commended Oakland, Calif., for conducting a rigorous problem analysis of violent crime. It mentioned the Dallas, Texas, mayor’s office and police department for evolving a multi-disciplinary response and a strategic plan to organize efforts at addressing violent crime effectively.

“Outreach workers in neighborhoods and hospitals where shooting victims are recovering can defuse conflicts, connect people to services, and serve as crucial go-betweens for a city and some of its most disconnected citizens, as they do in New York City,” the report added.

The New York City’s Mayor’s office has a section targeted at preventing gun violence. “From 2010 to 2019, data show the Crisis Management System has contributed to an average 40% reduction in shootings across program areas compared to 31% decline in shootings in the 17 highest violence precincts in New York City,” the city stated.

Ivey told the Mississippi Free Press that addressing the root causes of violence should be a priority.

“You got fatherless homes; you have rap culture, this garbage music that these kids are enveloping their lives with; alcoholism at home, drug use at home, crumbling infrastructure in their neighborhoods,” he said. “When they walk outside, all the houses in the neighborhoods around them are just condemned and rotting, and they feel like that’s where they come from.”

“They feel like they have no worth, you know, and some of their parents aren’t really engaging in their lives,” Ivey added. “When you get these young men and women on the wrong path, doing drugs, committing violence, selling drugs, committing crimes, you need somebody that they can relate to, to stop them from doing that,” he said.

He said violence interrupters—another name for credible messengers and street-outreach workers—know and connect to the neighborhood, are aware of the crisis when it starts developing, and can relate with the young men and women to stop doing wrong.

“They know when there’s a beef between people, they know when there’s a problem between people, and they can get ahead of it and stop the shooting before it ever happens,” he explained. “But instead of funding people, organizations like us (with) preventive measures, they want to wait until people are getting shot, they want to wait until after people are doing the shooting to have them arrested and sent to jail, right?”

“That’s not stopping violence; all that is doing is locking people up because when those people get locked up, those same root problems are still going on in the neighborhoods,” he added. “Those same root problems are still happening in the community, and nothing is being done to stop the root problems.”